15.3 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Trapped in a Loop

You may have had the experience of having an irresistible urge to go back to check whether you actually locked the door or turned off the oven, even when you’re pretty sure that you did. Or you may have been unable to resist engaging in some superstitious behavior, such as wearing your lucky shirt on a date or to a sporting event. In some people, such thoughts and actions spiral out of control and become a serious problem.

Karen, a 34-

Karen’s preoccupation with numbers extended to other activities, most notably, the pattern in which she smoked cigarettes and drank coffee. If she had one cigarette, she felt that she had to smoke at least four in a row or one of her children would be harmed in some way. If she drank one cup of coffee, she felt compelled to drink four more to protect her children from harm. She acknowledged that her counting rituals were irrational, but she became extremely anxious when she tried to stop (Oltmanns, Neale, & Davison, 1991).

How effective is willful effort at curing OCD?

Karen’s symptoms are typical of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), in which repetitive, intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and ritualistic behaviors (compulsions) designed to fend off those thoughts interfere significantly with an individual’s functioning. Anxiety plays a role in this disorder because the obsessive thoughts typically produce anxiety, and the compulsive behaviors are performed to reduce it. In OCD, these obsessions and compulsions are intense, frequent, and experienced as irrational and excessive. Attempts to cope with the obsessive thoughts by trying to suppress or ignore them are of little or no benefit. In fact (as discussed in the Consciousness chapter), thought suppression can backfire, increasing the frequency and intensity of the obsessive thoughts (Wegner, 1989; Wenzlaff & Wegner, 2000). Despite anxiety’s role, in DSM–5 OCD is classified separately from anxiety disorders because the disorder is believed to have a distinct cause and to be maintained via different neural circuitry in the brain than the anxiety disorders.

599

Although 28% of adults in the United States report experiencing obsessions or compulsions at some point in their lives (Ruscio et al., 2010), only 2% will develop actual OCD (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005). Similar to anxiety disorders, rates of OCD are higher among women than men (Kessler et al., 2012). Among those with OCD, the most common obsessions and compulsions involve checking (79% of those with OCD), ordering (57%), moral concerns (43%), and contamination (26%; Ruscio et al., 2010). Although compulsive behavior is always excessive, it can vary considerably in intensity and frequency. For example, fear of contamination may lead to 15 minutes of hand washing in some individuals, whereas others may need to spend hours with disinfectants and extremely hot water, scrubbing their hands until they bleed.

The obsessions that plague individuals with OCD typically derive from concerns that could pose a real threat (such as contamination or disease), which supports preparedness theory. Thinking repeatedly about whether we’ve left a stove burner on when we leave the house makes sense, after all, if we want to return to a house that is not “well done.” The concept of preparedness places OCD in the same evolutionary context as phobias (Szechtman & Woody, 2006). However, as with phobias, we need to consider other factors to explain why fears that may have served an evolutionary purpose can become so distorted and maladaptive.

Family studies indicate a moderate genetic heritability for OCD: Identical twins show a higher concordance than do fraternal twins. Relatives of individuals with OCD may not have the disorder themselves, but they are at greater risk for other types of anxiety disorders than are members of the general public (Billet, Richter, & Kennedy, 1998). Researchers have not determined the biological mechanisms that may contribute to OCD (Friedlander & Desrocher, 2006), but one hypothesis implicates heightened neural activity in the caudate nucleus of the brain, a portion of the basal ganglia (discussed in the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter) known to be involved in the initiation of intentional actions (Rappoport, 1990). Drugs that increase the activity of the neurotransmitter serotonin in the brain can inhibit the activity of the caudate nucleus and relieve some of the symptoms of obsessive-

People with obsessive-

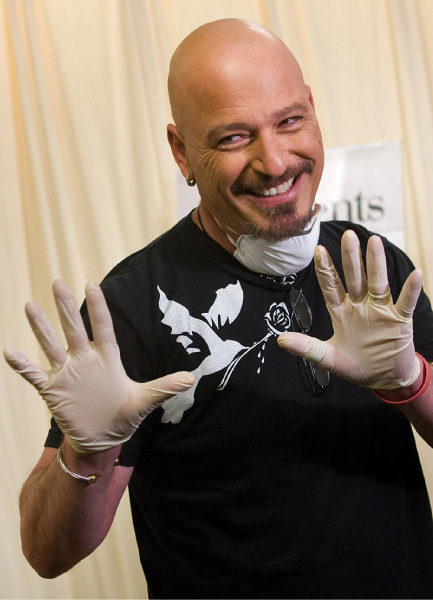

People with obsessive-compulsive disorder experience recurring, anxiety- provoking thoughts that compel them to engage in ritualistic, irrational behavior.