15.4 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Troubles after a Trauma

Psychological reactions to stress can lead to stress disorders. For example, a person who lives through a terrifying and uncontrollable experience may develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a disorder characterized by chronic physiological arousal, recurrent unwanted thoughts or images of the trauma, and avoidance of things that call the traumatic event to mind.

Psychological scars left by traumatic events are nowhere more apparent than in war. Many soldiers returning from combat experience symptoms of PTSD, including flashbacks of battle, exaggerated anxiety and startle reactions, and even medical conditions that do not arise from physical damage (e.g., paralysis or chronic fatigue). Most of these symptoms are normal, appropriate responses to horrifying events, and for most people, the symptoms subside with time. In PTSD, the symptoms can last much longer. For example, approximately 12% of U.S. veterans of recent operations in Iraq met criteria for PTSD after their deployment; and the observed rates of PTSD are even higher in non-

What structure in the brain might be an indicator for susceptibility to PTSD?

600

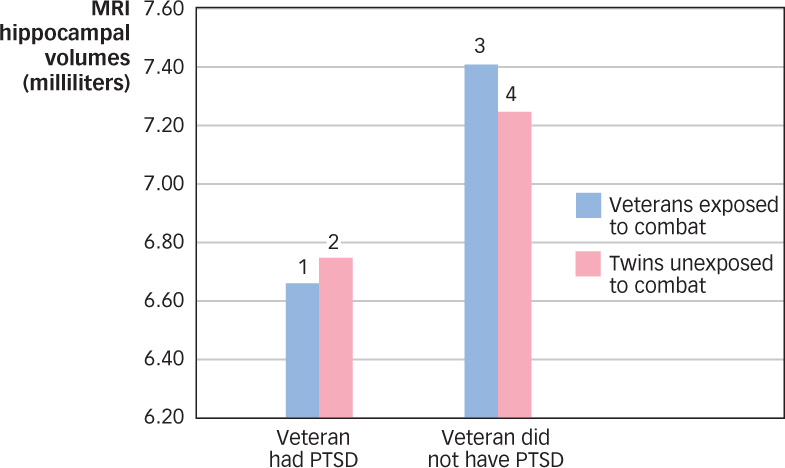

Not everyone who is exposed to a traumatic event develops PTSD, suggesting that people differ in their degree of sensitivity to trauma. Research using brain imaging techniques to examine brain structure and function has identified important neural correlates of PTSD. Specifically, those with PTSD show heightened activity in the amygdala (a region associated with the evaluation of threatening information and fear conditioning), decreased activity in the medial prefrontal cortex (a region important in the extinction of fear conditioning), and a smaller sized hippocampus (the part of the brain most linked with memory, as described in the Neuroscience and Behavior and Memory chapters; Shin, Rauch, & Pitman, 2006). Of course, an important question is whether people whose brains have these characteristics are at greater risk for PTSD if traumatized, or if these are the consequences of trauma in some people. For instance, does reduced hippocampal volume reflect a preexisting condition that makes the brain sensitive to stress, or does the traumatic stress itself somehow kill nerve cells? One important study suggests that although a group of combat veterans with PTSD showed reduced hippocampal volume, so did the identical (monozygotic) twins of those men (see FIGURE 15.1), even though the twins had never had any combat exposure or developed PTSD (Gilbertson et al., 2002). This suggests that the veterans’ reduced hippocampal volumes weren’t caused by the combat exposure; instead, both these veterans and their twin brothers might have had a smaller hippocampus to begin with, a preexisting condition that made them susceptible to developing PTSD when they were later exposed to trauma.

Figure 15.1: Hippocampal Volumes of Vietnam Veterans and Their Identical Twins Average hippocampal volumes for four groups of participants: (1) combat-

Figure 15.1: Hippocampal Volumes of Vietnam Veterans and Their Identical Twins Average hippocampal volumes for four groups of participants: (1) combat-601

Terrifying, life-

Terrifying, life-threatening events, such as combat experience or rape, can lead to the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in which a person experiences chronic physiological arousal, unwanted thoughts or images of the event, and avoidance of things that remind the person of the event.