15.6 Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders: Losing the Grasp on Reality

Margaret, a 39-

Symptoms and Types of Schizophrenia

What is schizophrenia?

Schizophrenia is a psychotic disorder (psychosis is a break from reality) characterized by the profound disruption of basic psychological processes; a distorted perception of reality; altered or blunted emotion; and disturbances in thought, motivation, and behavior. Traditionally, schizophrenia was regarded primarily as a disturbance of thought and perception, in which the sense of reality becomes severely distorted and confused. However, this condition is now understood to take different forms affecting a wide range of functions. According to the DSM–5, schizophrenia is diagnosed when two or more symptoms emerge during a continuous period of at least 1 month with signs of the disorder persisting for at least 6 months. The symptoms of schizophrenia often are separated into positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms.

608

Positive symptoms of schizophrenia include thoughts and behaviors not seen in those without the disorder, such as

Hallucinations are false perceptual experiences that have a compelling sense of being real despite the absence of external stimulation. The perceptual disturbances associated with schizophrenia can include hearing, seeing, smelling, or having a tactile sensation of things that are not there. Schizophrenic hallucinations are often auditory (e.g., hearing voices that no one else can hear). Among people with schizophrenia, some 65% report hearing voices repeatedly (Frith & Fletcher, 1995). British psychiatrist Henry Maudsley (1886) long ago proposed that these voices are in fact produced in the mind of the person with schizophrenia, and recent research substantiates his idea. In one PET imaging study, auditory hallucinations were accompanied by activation in Broca’s area (as discussed in the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter), the part of the brain associated with the production of language (McGuire, Shah, & Murray, 1993). Unfortunately, the voices heard in schizophrenia seldom sound like the self or like a kindly uncle offering advice. They command, scold, suggest bizarre actions, or offer snide comments. One individual reported a voice saying, “He’s getting up now. He’s going to wash. It’s about time” (Frith & Fletcher, 1995).

Hallucinations are false perceptual experiences that have a compelling sense of being real despite the absence of external stimulation. The perceptual disturbances associated with schizophrenia can include hearing, seeing, smelling, or having a tactile sensation of things that are not there. Schizophrenic hallucinations are often auditory (e.g., hearing voices that no one else can hear). Among people with schizophrenia, some 65% report hearing voices repeatedly (Frith & Fletcher, 1995). British psychiatrist Henry Maudsley (1886) long ago proposed that these voices are in fact produced in the mind of the person with schizophrenia, and recent research substantiates his idea. In one PET imaging study, auditory hallucinations were accompanied by activation in Broca’s area (as discussed in the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter), the part of the brain associated with the production of language (McGuire, Shah, & Murray, 1993). Unfortunately, the voices heard in schizophrenia seldom sound like the self or like a kindly uncle offering advice. They command, scold, suggest bizarre actions, or offer snide comments. One individual reported a voice saying, “He’s getting up now. He’s going to wash. It’s about time” (Frith & Fletcher, 1995). Delusions are patently false beliefs, often bizarre and grandiose, that are maintained in spite of their irrationality. For example, an individual with schizophrenia may believe that he or she is Jesus Christ, Napoleon, Joan of Arc, or some other well-

Delusions are patently false beliefs, often bizarre and grandiose, that are maintained in spite of their irrationality. For example, an individual with schizophrenia may believe that he or she is Jesus Christ, Napoleon, Joan of Arc, or some other well-known person. Such delusions of identity have helped foster the misconception that schizophrenia involves multiple personalities. However, adopted identities in schizophrenia do not alternate, exhibit amnesia for one another, or otherwise “split.” Delusions of persecution are also common. Some individuals believe that the CIA, demons, extraterrestrials, or other malevolent forces are conspiring to harm them or control their minds, which may represent an attempt to make sense of the tormenting delusions (Roberts, 1991). People with schizophrenia have little or no insight into their disordered perceptual and thought processes (Karow et al., 2007). Without understanding that they have lost control of their own minds, they may develop unusual beliefs and theories that attribute control to external agents.  Disorganized speech is a severe disruption of verbal communication in which ideas shift rapidly and incoherently among unrelated topics. The abnormal speech patterns in schizophrenia reflect difficulties in organizing thoughts and focusing attention. Responses to questions are often irrelevant, ideas are loosely associated, and words are used in peculiar ways. For example, asked by her doctor, “Can you tell me the name of this place?” one patient with schizophrenia responded, “I have not been a drinker for 16 years. I am taking a mental rest after a ‘carter’ assignment of ‘quill.’ You know, a ‘penwrap.’ I had contracts with Warner Brothers Studios and Eugene broke phonograph records but Mike protested. I have been with the police department for 35 years. I am made of flesh and blood—

Disorganized speech is a severe disruption of verbal communication in which ideas shift rapidly and incoherently among unrelated topics. The abnormal speech patterns in schizophrenia reflect difficulties in organizing thoughts and focusing attention. Responses to questions are often irrelevant, ideas are loosely associated, and words are used in peculiar ways. For example, asked by her doctor, “Can you tell me the name of this place?” one patient with schizophrenia responded, “I have not been a drinker for 16 years. I am taking a mental rest after a ‘carter’ assignment of ‘quill.’ You know, a ‘penwrap.’ I had contracts with Warner Brothers Studios and Eugene broke phonograph records but Mike protested. I have been with the police department for 35 years. I am made of flesh and blood—see, Doctor” [pulling up her dress] (Carson et al., 2000, p. 474).  Grossly disorganized behavior is behavior that is inappropriate for the situation or ineffective in attaining goals, often with specific motor disturbances. An individual might exhibit constant childlike silliness, improper sexual behavior (such as masturbating in public), disheveled appearance, or loud shouting or swearing. Specific motor disturbances might include strange movements, rigid posturing, odd mannerisms, bizarre grimacing, or hyperactivity. Catatonic behavior is a marked decrease in all movement or an increase in muscular rigidity and overactivity. Individuals with catatonia may actively resist movement (when someone is trying to move them) or become completely unresponsive and unaware of their surroundings in a catatonic stupor. In addition, individuals receiving drug therapy may exhibit motor symptoms (such as rigidity or spasm) as a side effect of the medication. Indeed, the DSM–5 includes a diagnostic category labeled medication-

Grossly disorganized behavior is behavior that is inappropriate for the situation or ineffective in attaining goals, often with specific motor disturbances. An individual might exhibit constant childlike silliness, improper sexual behavior (such as masturbating in public), disheveled appearance, or loud shouting or swearing. Specific motor disturbances might include strange movements, rigid posturing, odd mannerisms, bizarre grimacing, or hyperactivity. Catatonic behavior is a marked decrease in all movement or an increase in muscular rigidity and overactivity. Individuals with catatonia may actively resist movement (when someone is trying to move them) or become completely unresponsive and unaware of their surroundings in a catatonic stupor. In addition, individuals receiving drug therapy may exhibit motor symptoms (such as rigidity or spasm) as a side effect of the medication. Indeed, the DSM–5 includes a diagnostic category labeled medication-induced movement disorders that identifies motor disturbances arising from the use of medications of the sort commonly used to treat schizophrenia.

609

Negative symptoms are deficits or disruptions to normal emotions and behaviors. They include emotional and social withdrawal; apathy; poverty of speech; and other indications of the absence or insufficiency of normal behavior, motivation, and emotion. These symptoms refer to things missing in people with schizophrenia. Negative symptoms may rob people of emotion, for example, leaving them with flat, deadpan responses; their interest in people or events may be undermined, or their capacity to focus attention may be impaired.

Cognitive symptoms are deficits in cognitive abilities, specifically in executive functioning, attention, and working memory. These are the most difficult symptoms to notice because they are much less bizarre and public than the positive and negative symptoms. However, these cognitive deficits often play a large role in terms of preventing people with schizophrenia from achieving a high level of functioning, such as maintaining friendships and holding down a job (Green et al., 2000).

Schizophrenia occurs in about 1% of the population (Jablensky, 1997) and is slightly more common in men than in women (McGrath et al., 2008). Early versions of the DSM suggested that schizophrenia might have a very early onset—

Biological Factors

In 1899, when German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin first described the syndrome we now know as schizophrenia, he remarked that the disorder was so severe that it suggested “organic,” or biological, origins. Over the years, accumulating evidence for the role of biology in schizophrenia has come from studies of genetic factors, biochemical factors, and neuroanatomy.

Genetic Factors

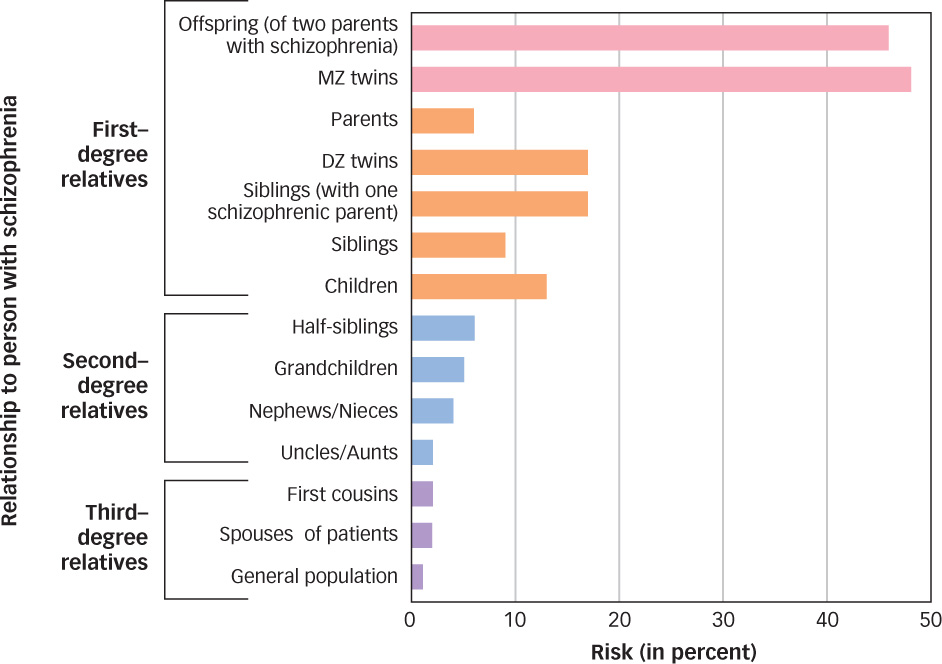

Family studies indicate that the closer a person’s genetic relatedness to a person with schizophrenia, the greater the likelihood of developing the disorder (Gottesman, 1991). As shown in FIGURE 15.4, concordance rates increase dramatically with biological relatedness. The rates are estimates and vary considerably from study to study, but almost every study finds the average concordance rates higher for identical twins (48%) than for fraternal twins (17%), which suggests a genetic component for the disorder (Torrey et al., 1994).

Figure 15.4: Average Risk of Developing Schizophrenia The risk of schizophrenia among biological relatives is greater for those with greater degrees of relatedness. An identical (MZ) twin of a twin with schizophrenia has a 48% risk of developing schizophrenia, for example, and offspring of two parents with schizophrenia have a 46% risk of developing the disorder.

Figure 15.4: Average Risk of Developing Schizophrenia The risk of schizophrenia among biological relatives is greater for those with greater degrees of relatedness. An identical (MZ) twin of a twin with schizophrenia has a 48% risk of developing schizophrenia, for example, and offspring of two parents with schizophrenia have a 46% risk of developing the disorder.

What is the role of genetics in schizophrenia?

610

Although genetics clearly have a strong predisposing role in schizophrenia, considerable evidence suggests that environmental factors, such as the prenatal and perinatal environments, also affect concordance rates (Jurewicz, Owen, & O’Donovan, 2001; Thaker, 2002; Torrey et al., 1994). For example, because approximately 70% of identical twins share the same prenatal blood supply, toxins in the mother’s blood could contribute to the high concordance rate. More recent studies (discussed in the earlier section on bipolar disorder) are contributing to a better understanding of how environmental stressors can trigger epigenetic changes that increase susceptibility to this disorder.

Biochemical Factors

During the 1950s, major tranquilizers were discovered that could reduce the symptoms of schizophrenia by lowering levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine. The effectiveness of many drugs in alleviating schizophrenic symptoms is related to the drugs’ capacity to reduce dopamine’s role in neurotransmission in certain brain tracts. This finding suggested the dopamine hypothesis, the idea that schizophrenia involves an excess of dopamine activity. The hypothesis has been invoked to explain why amphetamines, which increase dopamine levels, often exacerbate symptoms of schizophrenia (Iverson, 2006).

If only things were so simple. Considerable evidence suggests that this hypothesis is inadequate (Moncrieff, 2009). For example, many individuals with schizophrenia do not respond favorably to dopamine-

611

Neuroanatomy

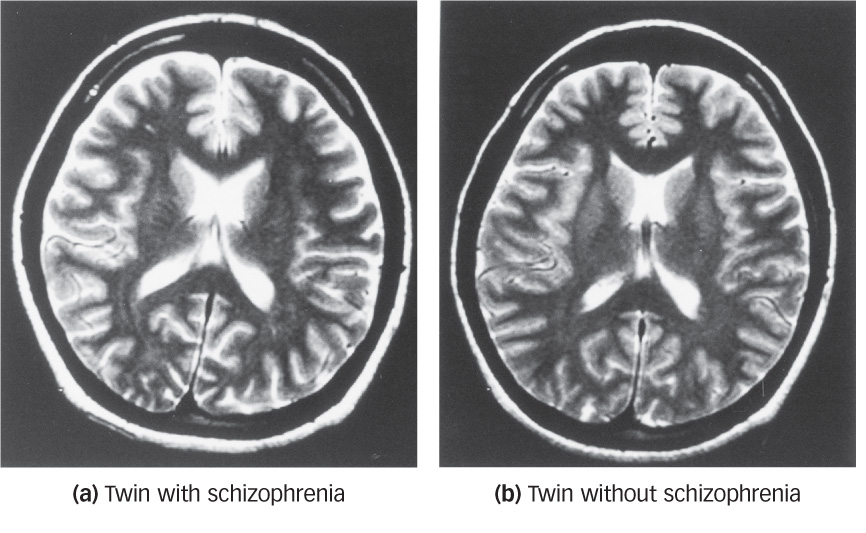

When neuroimaging techniques became available, researchers immediately started looking for distinctive anatomical features of the brain in individuals with schizophrenia. The earliest observations revealed enlargement of the ventricles, hollow areas filled with cerebrospinal fluid, lying deep within the core of the brain (see FIGURE 15.5; Johnstone et al., 1976). In some individuals (primarily those with chronic, negative symptoms), the ventricles were abnormally enlarged, suggesting a loss of brain tissue mass that could arise from an anomaly in prenatal development (Arnold et al., 1998; Heaton et al., 1994).

Figure 15.5: Enlarged Ventricles in Schizophrenia These MRI scans of monozygotic twins reveal that (a) the twin affected by schizophrenia shows enlarged ventricles (all the central white space) as compared to (b) the unaffected twin (Kunugi et al., 2003).

Figure 15.5: Enlarged Ventricles in Schizophrenia These MRI scans of monozygotic twins reveal that (a) the twin affected by schizophrenia shows enlarged ventricles (all the central white space) as compared to (b) the unaffected twin (Kunugi et al., 2003).

How are the brains of people with schizophrenia different from those without this disorder?

Understanding the significance of this brain abnormality for schizophrenia is complicated by several factors, however. First, such enlarged ventricles are found in only a minority of cases of schizophrenia. Second, some individuals who do not have schizophrenia also show evidence of enlarged ventricles. Finally, this type of brain abnormality can be caused by the long-

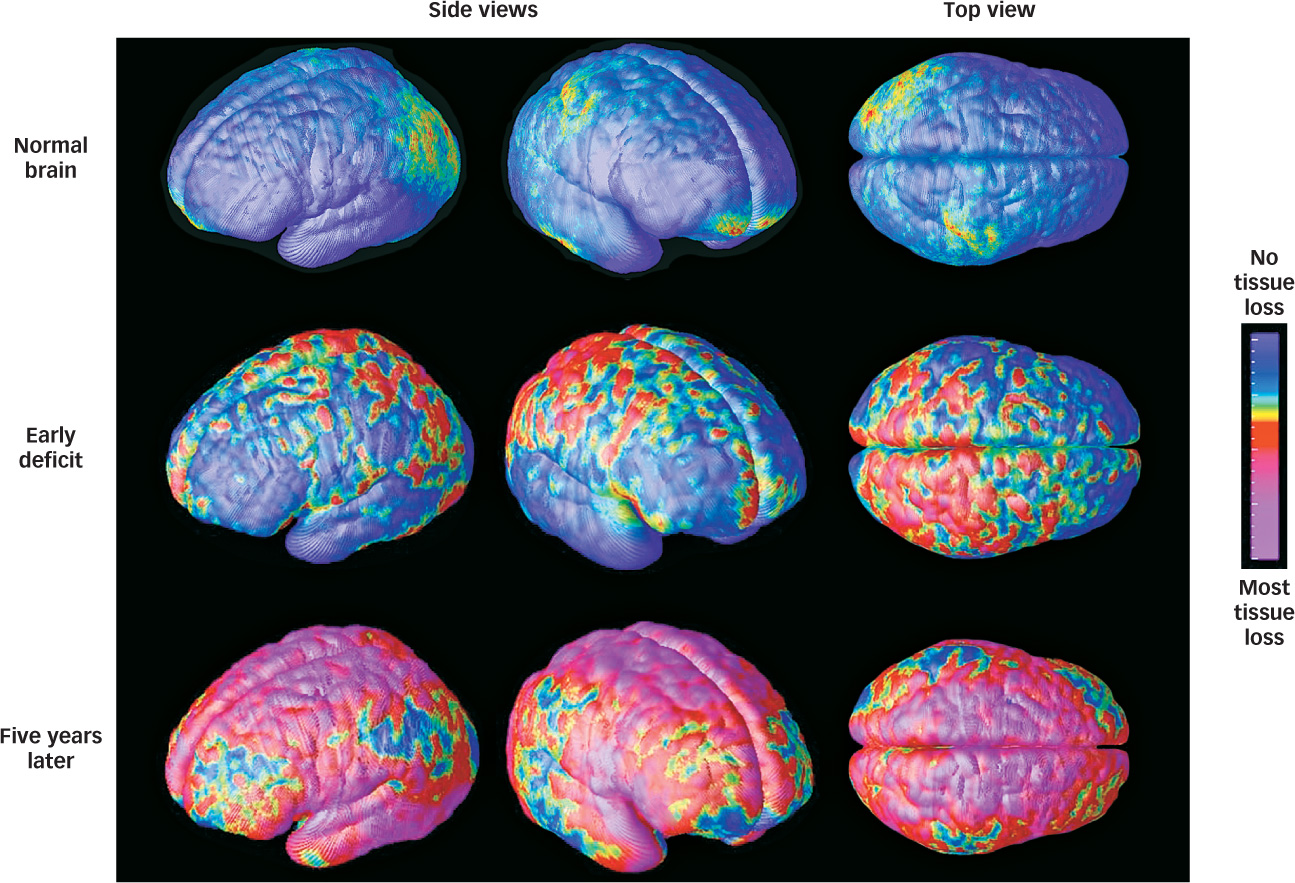

Neuroimaging studies provide evidence of a variety of brain abnormalities in schizophrenia. Paul Thompson and his colleagues (2001) examined changes in the brains of adolescents whose MRI scans could be traced sequentially from the onset of schizophrenia. By morphing the images onto a standardized brain, the researchers were able to detect progressive tissue loss beginning in the parietal lobe and eventually encompassing much of the brain (see FIGURE 15.6). All adolescents lose some gray matter over time in a kind of normal “pruning” of the brain, but in the case of those developing schizophrenia, the loss was dramatic enough to seem pathological. A variety of specific brain changes found in other studies suggests a clear relationship between biological changes in the brain and the progression of schizophrenia (Shenton et al., 2001).

Figure 15.6: Brain Tissue Loss in Adolescent Schizophrenia MRI scan composites reveal brain tissue loss in adolescents diagnosed with schizophrenia. Normal brains show minimal loss due to “pruning” (top). Early-

Figure 15.6: Brain Tissue Loss in Adolescent Schizophrenia MRI scan composites reveal brain tissue loss in adolescents diagnosed with schizophrenia. Normal brains show minimal loss due to “pruning” (top). Early-Psychological Factors

With all these potential biological contributors to schizophrenia, you might think there would be few psychological or social causes of the disorder. However, several studies do suggest that the family environment plays a role in the development of and recovery from the condition. One large-

612

Schizophrenia is a severe psychological disorder involving hallucinations, disorganized thoughts and behavior, and emotional and social withdrawal.

Schizophrenia is a severe psychological disorder involving hallucinations, disorganized thoughts and behavior, and emotional and social withdrawal. Schizophrenia affects only 1% of the population, but it accounts for a disproportionate share of psychiatric hospitalizations.

Schizophrenia affects only 1% of the population, but it accounts for a disproportionate share of psychiatric hospitalizations. The first drugs that reduced the availability of dopamine sometimes reduced the symptoms of schizophrenia, suggesting that the disorder involved an excess of dopamine activity, but recent research suggests that schizophrenia may involve a complex interaction among a variety of neurotransmitters.

The first drugs that reduced the availability of dopamine sometimes reduced the symptoms of schizophrenia, suggesting that the disorder involved an excess of dopamine activity, but recent research suggests that schizophrenia may involve a complex interaction among a variety of neurotransmitters. Risks for developing schizophrenia include genetic factors, biochemical factors (perhaps a complex interaction among many neurotransmitters), brain abnormalities, and a stressful home environment.

Risks for developing schizophrenia include genetic factors, biochemical factors (perhaps a complex interaction among many neurotransmitters), brain abnormalities, and a stressful home environment.

613

OTHER VOICES: Successful and Schizophrenic

This chapter describes what we know about the characteristics and causes of mental disorders, and the next chapter describes how these disorders are commonly treated. For some of the more severe disorders, such as schizophrenia, the picture does not look good. People diagnosed with schizophrenia often are informed that it is a lifelong condition, and although current treatments show some effectiveness in decreasing the delusional thinking and hallucinations often present in those with schizophrenia, people with this disorder often are unable to hold down a full-

Elyn Saks is one such person who received a diagnosis of schizophrenia and was informed of this prognosis. She described what happened next in a longer version of the following article that appeared in the New York Times (2013).

Thirty years ago, I was given a diagnosis of schizophrenia. My prognosis was “grave”: I would never live independently, hold a job, find a loving partner, get married. My home would be a board-

Then I made a decision. I would write the narrative of my life. Today I am a chaired professor at the University of Southern California Gould School of Law. I have an adjunct appointment in the department of psychiatry at the medical school of the University of California, San Diego. The MacArthur Foundation gave me a genius grant.

Although I fought my diagnosis for many years, I came to accept that I have schizophrenia and will be in treatment the rest of my life…. What I refused to accept was my prognosis.

Conventional psychiatric thinking and its diagnostic categories say that people like me don’t exist. Either I don’t have schizophrenia (please tell that to the delusions crowding my mind), or I couldn’t have accomplished what I have (please tell that to U.S.C.’s committee on faculty affairs). But I do, and I have. And I have undertaken research with colleagues at U.S.C. and U.C.L.A. to show that I am not alone. There are others with schizophrenia and such active symptoms as delusions and hallucinations who have significant academic and professional achievements.

Over the last few years, my colleagues…and I have gathered 20 research subjects with high-

How had these people with schizophrenia managed to succeed in their studies and at such high-

Other techniques that our participants cited included controlling sensory inputs. For some, this meant keeping their living space simple (bare walls, no TV, only quiet music), while for others, it meant distracting music. “I’ll listen to loud music if I don’t want to hear things,” said a participant who is a certified nurse’s assistant. Still others mentioned exercise, a healthy diet, avoiding alcohol and getting enough sleep….

One of the most frequently mentioned techniques that helped our research participants manage their symptoms was work. “Work has been an important part of who I am,” said an educator in our group. “When you become useful to an organization and feel respected in that organization, there’s a certain value in belonging there.” This person works on the weekends too because of “the distraction factor.” In other words, by engaging in work, the crazy stuff often recedes to the sidelines….

THAT is why it is so distressing when doctors tell their patients not to expect or pursue fulfilling careers. Far too often, the conventional psychiatric approach to mental illness is to see clusters of symptoms that characterize people. Accordingly, many psychiatrists hold the view that treating symptoms with medication is treating mental illness. But this fails to take into account individuals’ strengths and capabilities, leading mental health professionals to underestimate what their patients can hope to achieve in the world….A recent New York Times Magazine article described a new company that hires high-

An approach that looks for individual strengths, in addition to considering symptoms, could help dispel the pessimism surrounding mental illness. Finding “the wellness within the illness,” as one person with schizophrenia said, should be a therapeutic goal. Doctors should urge their patients to develop relationships and engage in meaningful work. They should encourage patients to find their own repertory of techniques to manage their symptoms and aim for a quality of life as they define it. And they should provide patients with the resources—

Elyn Saks’s story is amazing and inspiring. It also is quite unusual. How should we incorporate stories like hers and the people in the research study she described? Are these people outliers—

From the New York Times, January 25, 2013. © 2013 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited. http:/

614