15.8 Personality Disorders: Going to Extremes

Think for a minute about high school acquaintances whose personalities made them stand out—

Types of Personality Disorders

The DSM–5 lists 10 specific personality disorders (see TABLE 15.3). They fall into three clusters: (a) odd/eccentric, (b) dramatic/erratic, and (c) anxious/inhibited. The strange high school student, for example, could have schizotypal personality disorder (odd/eccentric cluster); the drama queen could have histrionic personality disorder (dramatic/erratic cluster); the neat freak could have obsessive-

Personality disorders have been a bit controversial for several reasons. First, critics question whether having a problematic personality is really a disorder. Given that approximately 15% of the U.S. population has a personality disorder according to the DSM–5, perhaps it might be better just to admit that a lot of people are difficult and leave it at that. Another question is whether personality problems correspond to “disorders” in that there are distinct types or whether such problems might be better understood as extreme values on trait dimensions such as the Big Five traits discussed in the Personality chapter (Trull & Durrett, 2005). In DSM–IV, personality disorders appeared as a separate type of disorder from all of the other disorders described above (specifically, those major disorders were all in a category called Axis I and personality disorders were in Axis II). However, in DSM–5 personality disorders have earned equal footing as full-

| Cluster | Personality Disorder | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| A. Odd/ Eccentric | Paranoid | Distrust in others, suspicion that people have sinister motives. Apt to challenge the loyalties of friends and read hostile intentions into others’ actions. Prone to anger and aggressive outbursts but otherwise emotionally cold. Often jealous, guarded, secretive, overly serious. |

| Schizoid | Extreme introversion and withdrawal from relationships. Prefers to be alone, little interest in others. Humorless, distant, often absorbed with own thoughts and feelings, a daydreamer. Fearful of closeness, with poor social skills, often seen as a “loner.” | |

| Schizotypal | Peculiar or eccentric manners of speaking or dressing. Strange beliefs. “Magical thinking” such as belief in ESP or telepathy. Difficulty forming relationships. May react oddly in conversation, not respond, or talk to self. Speech elaborate or difficult to follow. (Possibly a mild form of schizophrenia.) | |

| B. Dramatic/ Erratic | Antisocial | Impoverished moral sense or “conscience.” History of deception, crime, legal problems, impulsive and aggressive or violent behavior. Little emotional empathy or remorse for hurting others. Manipulative, careless, callous. At high risk for substance abuse and alcoholism. |

| Borderline | Unstable moods and intense, stormy personal relationships. Frequent mood changes and anger, unpredictable impulses. Self- |

|

| Histrionic | Constant attention seeking. Grandiose language, provocative dress, exaggerated illnesses, all to gain attention. Believes that everyone loves them. Emotional, lively, overly dramatic, enthusiastic, and excessively flirtatious. Shallow and labile emotions. “Onstage.” | |

| Narcissistic | Inflated sense of self- |

|

| C. Anxious/ Inhibited | Avoidant | Socially anxious and uncomfortable unless they are confident of being liked. In contrast with schizoid person, yearns for social contact. Fears criticism and worries about being embarrassed in front of others. Avoids social situations due to fear of rejection. |

| Dependent | Submissive, dependent, requiring excessive approval, reassurance, and advice. Clings to people and fears losing them. Lacking self- |

|

| Obsessive- |

Conscientious, orderly, perfectionist. Excessive need to do everything “right.” Inflexibly high standards and caution can interfere with their productivity. Fear of errors can make them strict and controlling. Poor expression of emotions. (Not the same as obsessive- |

|

| Source: From DSM–5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). | ||

619

Antisocial Personality Disorder

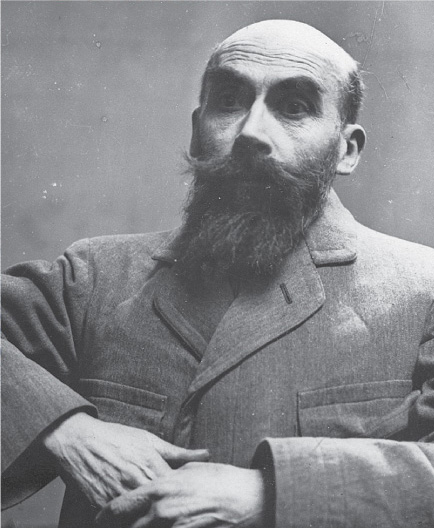

Henri Desiré Landru began using personal ads to attract a woman “interested in matrimony” in Paris in 1914, and he succeeded in seducing 10 of them. He bilked them of their savings, poisoned them, and cremated them in his stove, also disposing of a boy and two dogs along the way. He recorded his murders in a notebook and maintained a marriage and a mistress all the while. The gruesome actions of serial killers such as Landru leave us frightened and wondering; however, bullies, compulsive liars, and even drivers who regularly speed through a school zone share the same shocking blindness to human pain. The DSM–5 includes the category of antisocial personality disorder (APD) and defines it as a pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others that begins in childhood or early adolescence and continues into adulthood.

620

Adults with an APD diagnosis typically have a history of conduct disorder before the age of 15. In adulthood, a diagnosis of APD is given to individuals who show three or more of a set of seven diagnostic signs: illegal behavior, deception, impulsivity, physical aggression, recklessness, irresponsibility, and a lack of remorse for wrongdoing. About 3.6% of the general population has APD, and the rate of occurrence in men is 3 times the rate in women (Grant et al., 2004).

What are some of the factors that contribute to APD?

The terms sociopath and psychopath describe people with APD who are especially coldhearted, manipulative, and ruthless—

Both the early onset of conduct problems and the lack of success in treatment suggest that career criminality often has an internal cause (Lykken, 1995). Evidence of brain abnormalities in people with APD is also accumulating (Blair, Peschardt, & Mitchell, 2005). One line of investigation has looked at sensitivity to fear in psychopaths and individuals who show no such psychopathology. For example, criminal psychopaths who are shown negative emotional words such as hate or corpse exhibit less activity in the amygdala and hippocampus than do noncriminals (Kiehl et al., 2001). The two brain areas are involved in the process of fear conditioning (Patrick, Cuthbert, & Lang, 1994), so their relative inactivity in such studies suggests that psychopaths are less sensitive to fear than are other people. Violent psychopaths can target their aggression toward the self as well as others, often behaving in reckless ways that lead to violent ends. It might seem peaceful to go through life “without fear,” but perhaps fear is useful in keeping people from the extremes of antisocial behavior.

Personality disorders are enduring patterns of thinking, feeling, relating to others, or controlling impulses that cause distress or impaired functioning.

Personality disorders are enduring patterns of thinking, feeling, relating to others, or controlling impulses that cause distress or impaired functioning. They include three clusters: odd/eccentric, dramatic/erratic, and anxious/inhibited.

They include three clusters: odd/eccentric, dramatic/erratic, and anxious/inhibited. Antisocial personality disorder is associated with a lack of moral emotions and behavior; people with antisocial personality disorder can be manipulative, dangerous, and reckless, often hurting others and sometimes hurting themselves.

Antisocial personality disorder is associated with a lack of moral emotions and behavior; people with antisocial personality disorder can be manipulative, dangerous, and reckless, often hurting others and sometimes hurting themselves.

621