16.1 Treatment: Getting Help to Those Who Need It

What are some of the personal, social, and financial costs of mental illness?

Estimates suggest that 46.4% of people in the United States suffer from some type of mental disorder at some point in their lifetime (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005), and 26.2% suffer from at least one disorder during a given year (Kessler, Chiu, et al., 2005). The personal costs of these disorders involve anguish to the sufferers as well as interference in their ability to carry on the activities of daily life. Think about Christine from the example above. If she did not (or could not) seek treatment, she would continue to be crippled by her OCD, which was causing major problems in her life. She had to quit her job at the local coffee shop because she was no longer able to touch money or anything else that had been touched by other people without washing it first. Her relationship with her boyfriend was in trouble because he was growing tired of her constant reassurance seeking regarding cleanliness (hers and his). All of these problems were in turn increasing her anxiety and depression, making her obsessions even stronger. She desperately wanted and needed some way to break out of this vicious cycle. She needed an effective treatment.

The personal and social burdens associated with mental disorders are also enormous. Mental disorders typically have earlier ages of onset than physical disorders and are associated with significant impairments in the form of an inability to carry out daily activities, such as days out of school or work or problems in family and personal relationships. Impairments associated with mental disorders are as severe, and in many cases more severe, than those associated with physical disorders such as cancer, chronic pain, and heart disease (Ormel et al., 2008). For instance, a person with severe depression may be unable to hold down a job or even get organized enough to collect a disability check, and people with many disorders stop getting along with family, caring for their children, or trying to help.

There are financial costs too. Depression is the fourth leading cause of disability worldwide, and it is expected to rise to the second leading cause of disability by 2020 (Murray & Lopez, 1996a, 1996b). People with severe depression often are unable to make it into work due to their disorder, and even when they make it into work they often suffer from poor work performance. Recent estimates suggest that depression-

629

Do all people with a mental disorder receive treatment? Not by a long shot. Only about 18% of people in the United States with a mental disorder in the past 12 months received treatment during the same time frame. Treatment rates are even lower elsewhere around the world, especially in low-

Why Many People Fail to Seek Treatment

What are the obstacles to treatment for the mentally ill?

A physical symptom such as a toothache would send most people to the dentist—

- People may not realize that they have a mental disorder that could be effectively treated. Approximately 45% of those with a mental disorder who do not seek treatment report that they did not do so because they didn’t think that they needed to be treated (Mojtabai et al., 2011). Mental disorders often are not taken nearly as seriously as physical illness, perhaps because the origin of mental illness is “hidden” and usually cannot be diagnosed by a blood test or X-

ray. Moreover, although most people know what a toothache is and that it can be successfully treated, far fewer people know when they have a mental disorder and what treatments might be available. - There may be barriers to treatment, such as beliefs and circumstances that keep people from getting help. Individuals may believe that they should be able to handle things themselves. In fact, this is the primary reason that people with a mental disorder give for not seeking treatment (72.6%) and for dropping out of treatment prematurely (42.2%; Mojtabai et al., 2011). Other attitudinal barriers for not seeking treatment include believing that the problem was not that severe (16.9% of nontreatment seekers), the belief that treatment would be ineffective (16.4%), and perceived stigma from others (9.1%).

When your tooth hurts, you go to a dentist. But how do you know when to see a psychologist?ALLISON LEACH/GETTY IMAGES

When your tooth hurts, you go to a dentist. But how do you know when to see a psychologist?ALLISON LEACH/GETTY IMAGES - Structural barriers prevent people from physically getting to treatment. Like finding a good lawyer or plumber, finding the right psychologist can be more difficult than simply flipping through the yellow pages or searching online. This confusion is understandable given the plethora of different types of treatments available (see the Real World box, Types of Psychotherapists). Once you find the therapist for you, you may encounter structural barriers related to not being able to afford treatment (15.3% of nontreatment seekers), lack of clinician availability (12.8%), inconvenience of attending treatment (9.8%), and trouble finding transportation to the clinic (5.7%; Mojtabai et al., 2011).

Even when people seek and find help, they sometimes do not receive the most effective treatments, which further complicates things. For starters, most of the treatment of mental disorders is not provided by mental health specialists, but by general medical practitioners (Wang et al., 2007). And even when people make it to a mental health specialist, they do not always receive the most effective treatment possible. In fact, only a small percentage of those with a mental disorder (< 40%) receive what would be considered minimally adequate treatment, and only 15.3% of those with serious mental illness receive treatment that is considered minimally adequate. Inadequate treatment is especially a problem among those who are younger, African American, living in the Southern United States, diagnosed with a psychotic disorder, and treated in a general medical setting (Wang et al., 2002). Clearly, before choosing or prescribing a therapy, we need to know what kinds of treatments are available and understand which treatments are best for particular disorders.

630

THE REAL WORLD: Types of Psychotherapists

What do you do if you’re ready to seek the help of a mental health professional? To whom do you turn? Therapists have widely varying backgrounds and training, and this affects the kinds of services they offer. Before you choose a therapist, it is useful to have an understanding of a therapist’s background, training, and areas of expertise. There are several major “flavors.”

Psychologist A psychologist who practices psychotherapy holds a doctorate with specialization in clinical psychology (a PhD or PsyD). This degree takes about 5 years to complete and includes extensive training in therapy, the assessment of psychological disorders, and research. The psychologist will sometimes have a specialty, such as working with adolescents or helping people overcome sleep disorders, and will usually conduct therapy that involves talking. Psychologists must be licensed by the state, and most states require candidates to complete about 2 years of supervised practical training and a competency exam. If you look for a psychologist in the Yellow Pages or through a clinic, you will usually find someone with this background.

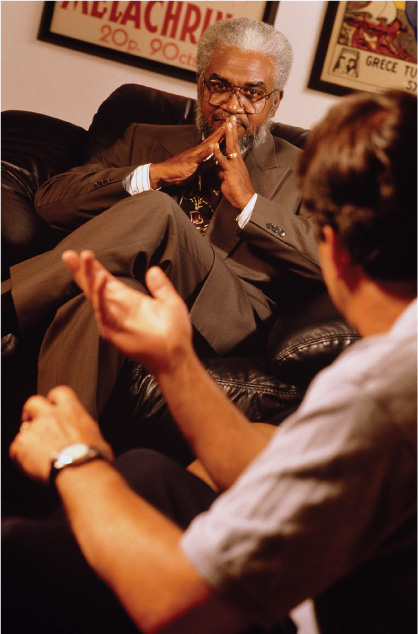

WAVEBREAKMEDIA LTD./GETTY IMAGES

WAVEBREAKMEDIA LTD./GETTY IMAGESPsychiatrist A psychiatrist is a medical doctor who has completed an M.D. with specialized training in assessing and treating mental disorders. Psychiatrists can prescribe medications, and some also practice psychotherapy. General practice physicians can also prescribe medications for mental disorders and often are the first to see people with such disorders because people consult them for a wide range of health problems. However, general practice physicians do not typically receive much training in the diagnosis or treatment of mental disorders, and they do not practice psychotherapy.

ZIGY KALUZNY/GETTY IMAGES

ZIGY KALUZNY/GETTY IMAGESSocial worker Social workers have a master’s degree in social work and have training in working with people in dire life situations such as poverty, homelessness, or family conflict. Clinical or psychiatric social workers also receive special training to help people in these situations who have mental disorders. Social workers often work in government or private social service agencies and may also work in hospitals or have a private practice.

Counselor Counselors have a wide range of training. To be a counseling psychologist, for example, requires a doctorate and practical training—

the title uses that key term psychologist and is regulated by state laws. But states vary in how they define counselor. In some cases, a counselor must have a master’s degree and extensive training in therapy, whereas in others, a counselor may have minimal training or relevant education. Counselors who work in schools usually have a master’s degree and specific training in counseling in educational settings.

Some people offer therapy under made-

How should you shop? One way is to start with people you know: your general practice physician, a school counselor, or a trusted friend or family member who might know of a good therapist. Or you can visit your college clinic or hospital or contact an Internet site of an organization such as the American Psychological Association that offers referrals to licensed mental health care providers. When you do contact someone, he or she will often be able to provide you with further advice about who would be just the right kind of therapist to consult.

Before you agree to see a therapist for treatment, you should ask questions such as those below to evaluate whether the therapist’s style or background is a good match for your problem:

- What type of therapy do you practice?

- What types of problems do you usually treat?

- For how long do you usually see people in therapy?

- Will our work involve “talking” therapy, medications, or both?

- How effective is this type of therapy for the type of problem I’m having?

- What are your fees for therapy, and will health insurance cover them?

Not only will the therapist’s answers to these questions tell you about his or her background and experience, but they will also tell you about his or her approach to treating clients. You can then make an informed decision about the type of service you need.

Although you should consider what type of therapist would best fit your needs, the therapist’s personality and approach can sometimes be as important as his or her background or training. You should seek out someone who is willing and open to answer questions, who has a clear understanding about the type of problem leading you to seek therapy, and who shows general respect and empathy for you. A therapist is someone you are entrusting with your mental health, and you should only enter into such a relationship when you and the therapist have good rapport.

Approaches to Treatment

Treatments can be divided broadly into two kinds: (a) psychological treatment, in which people interact with a clinician in order to use the environment to change their brain and behavior; and (b) biological treatment, in which the brain is treated directly with drugs, surgery or some other direct intervention. In some cases, both psychological and biological treatments are used. Christine’s OCD, for example, might be treated not only with the ERP but also with medication that decreases her obsessive thoughts and compulsive urges. For many years, psychological treatment was the main form of intervention for psychological disorders because few biological options were available. There have always been folk remedies that propose to have a biological basis—

632

CULTURE & COMMUNITY: Treatment of Psychological Disorders around the World

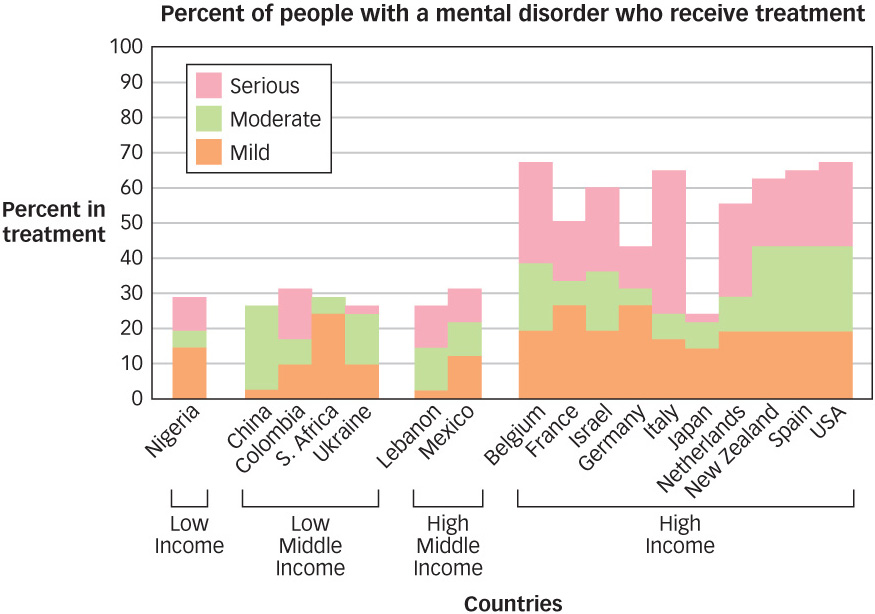

Barriers that keep people from receiving treatment for mental disorders exist all around the world. However, they are greater in some places than in others. One recent study examined what percentage of people with a mental disorder in 17 different countries around the world received treatment for their disorder in the past year (Wang et al., 2007). Several different findings are interesting to note. First, people with a severe mental disorder are much more likely to be treated. This makes sense. For instance, if your disorder is so severe that it prevents you from going to school or work you will probably seek treatment, but if it doesn’t really interfere with your daily life you may not go for help. Second, people living in high-

633

Mental illness is often misunderstood, and because of this, it too often goes untreated.

Mental illness is often misunderstood, and because of this, it too often goes untreated. Untreated mental illness can be extremely costly, affecting an individual’s ability to function and also causing social and financial burdens.

Untreated mental illness can be extremely costly, affecting an individual’s ability to function and also causing social and financial burdens. Many people who suffer from mental illness do not get the help they need; they may be unaware that they have a problem, they may be uninterested in getting help for their problem, or they may face structural barriers to getting treatment.

Many people who suffer from mental illness do not get the help they need; they may be unaware that they have a problem, they may be uninterested in getting help for their problem, or they may face structural barriers to getting treatment. Treatments include psychotherapy, which focuses on the mind, and medical and biological methods, which focus on the brain and body.

Treatments include psychotherapy, which focuses on the mind, and medical and biological methods, which focus on the brain and body.