16.4 Treatment Effectiveness: For Better or for Worse

Think back to Christine and the dead mouse at the beginning of the chapter. What if, instead of exposure and response prevention, Christine had been assigned psychoanalysis or psychosurgery? Could these alternatives have been just as effective (and justified) for treating her OCD? Through this chapter, we have explored various psychological and biological treatments that may help people with psychological disorders. But do these treatments actually work, and which ones work better than the others?

As you learned in the Methods in Psychology chapter, pinning down a specific cause for an effect can be a difficult detective exercise. The detection is made even more difficult because people may approach treatment evaluation very unscientifically, often by simply noticing an improvement (or no improvement, or even a worsening of symptoms) and reaching a conclusion based on that sole observation. Determination of a treatment’s effectiveness can be misdirected by illusions that can only be overcome by careful, scientific evaluation.

657

Treatment Illusions

What are three kinds of treatment illusions?

Imagine you’re sick and the doctor says, “Take a pill.” You follow the doctor’s orders, and you get better. To what do you attribute your improvement? If you’re like most people, you reach the conclusion that the pill cured you. That’s one possible explanation, but there are at least three others: Maybe you would have gotten better anyway; maybe the pill wasn’t the active ingredient in your cure; or maybe after you’re better, you mistakenly remember having been more ill than you really were. These possibilities point to three potential illusions of treatment: illusions produced by natural improvement, by placebo effects, and by reconstructive memory.

Natural Improvement

Natural improvement is the tendency of symptoms to return to their mean or average level. The illusion in this case happens when you conclude mistakenly that a treatment has made you better when you would have gotten better anyway. People typically turn to therapy or medication when their symptoms are at their worst. When this is the case, the client’s symptoms will often improve regardless of whether there was any treatment at all; when you’re at rock bottom, there’s nowhere to move but up. In most cases, for example, depression that becomes severe enough to make individuals candidates for treatment will tend to lift in several months no matter what they do. A person who enters therapy for depression may develop an illusion that the therapy works because the therapy coincides with the typical course of the illness and the person’s natural return to health. How can we know if change was caused by the treatment or by natural improvement? As discussed in the Methods in Psychology chapter, we could do an experiment in which we assign half of the people who are depressed to receive treatment and the other half to receive no treatment, and then monitor them over time to see if the ones who got treatment actually show greater improvement. This is precisely how researchers test out different interventions, as described in more detail below.

Placebo Effects

What is the placebo effect?

Recovery could be produced by nonspecific treatment effects that are not related to the specific mechanisms by which treatment is supposed to be working. For example, the doctor prescribing the medication might simply be a pleasant and hopeful individual who gives the client a sense of hope or optimism that things will improve. Client and doctor alike might attribute the client’s improvement to the effects of medication on the brain, whereas the true active ingredient was the warm relationship with the doctor or improved outlook on life.

Simply knowing that you are getting a treatment can be a nonspecific treatment effect. These instances include the positive influences that can be produced by a placebo, an inert substance or procedure that has been applied with the expectation that a healing response will be produced. For example, if you take a sugar pill that does not contain any painkiller for a headache thinking it is Tylenol or aspirin, this pill is a placebo. Placebos can have profound effects in the case of psychological treatments. Research shows that a large percentage of individuals with anxiety, depression, and other emotional and medical problems experience significant improvement after a placebo treatment (see The Real World: This is Your Brain on Placebos).

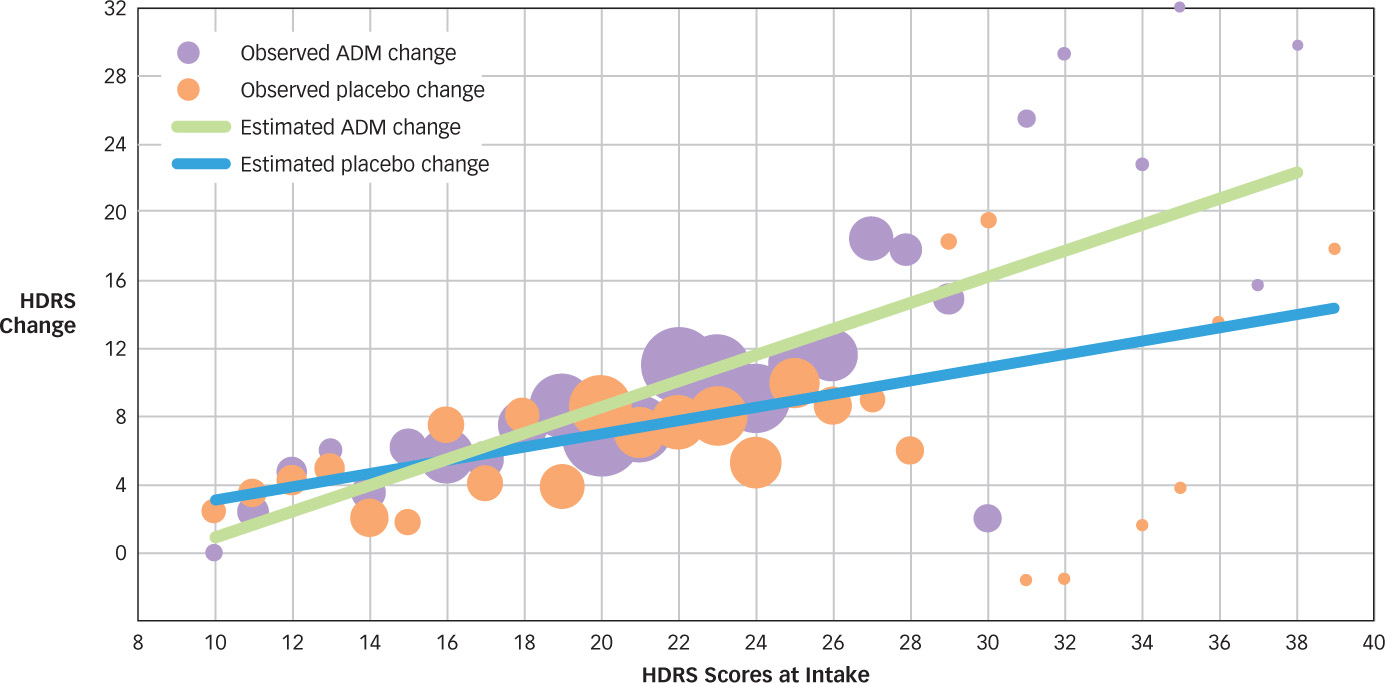

One recent study compared the decrease in symptoms of depression seen in 718 patients randomly assigned to receive either antidepressant medication or pill placebo (Fournier et al., 2010). Participants receiving medication showed a dramatic decrease in symptoms over the course of treatment. However, so did those taking placebo. Closer examination of the data revealed that for those with mild or moderate depression, placebo is just as effective as antidepressant medication at decreasing a person’s symptoms, and it is only in instances of severe depression that antidepressants seem to work better than placebo (see FIGURE 16.7).

Figure 16.7: Antidepressants versus Placebos for Depression A total of 713 depressed individuals from six different studies were given pills to treat their depression. Half were randomly assigned to receive an antidepressant medication (ADM) and half to receive a pill placebo. Importantly, the participants did not know if they were taking an antidepressant or simply a placebo. For those with mild or moderate depression, as measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), antidepressants did not work any better than placebo. However, those with severe depression showed much greater improvement on antidepressants than on placebo. The circle size represents the number of people with data at each point (from Fournier et al., 2010).

Figure 16.7: Antidepressants versus Placebos for Depression A total of 713 depressed individuals from six different studies were given pills to treat their depression. Half were randomly assigned to receive an antidepressant medication (ADM) and half to receive a pill placebo. Importantly, the participants did not know if they were taking an antidepressant or simply a placebo. For those with mild or moderate depression, as measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), antidepressants did not work any better than placebo. However, those with severe depression showed much greater improvement on antidepressants than on placebo. The circle size represents the number of people with data at each point (from Fournier et al., 2010).

658

Reconstructive Memory

A third treatment illusion can come about when the client’s motivation to get well causes errors in reconstructive memory for the original symptoms. You might think that you’ve improved because of a treatment when in fact you’re simply misremembering: mistakenly believing that your symptoms before treatment were worse than they actually were. This tendency was first observed in research examining the effectiveness of a study skills class (Conway & Ross, 1984). Some students who wanted to take the class were enrolled, but others were randomly assigned to a waiting list until the class could be offered again. When their study abilities were measured afterward, those students who took the class were no better at studying than their wait-

Treatment Studies

How can we make sure that we are using treatments that actually work and not wasting time with procedures that may be useless or even harmful? Research psychologists use the approaches covered in the Methods in Psychology chapter to create experiments that test whether treatments are effective for the different mental disorders described in the previous chapter.

Treatment outcome studies are designed to evaluate whether a particular treatment works, often in relation to some other treatment or a control condition. For example, to study the outcome of treatment for depression, researchers might compare the selfreported symptoms of two groups of people who were initially depressed: those who received treatment for 6 weeks and a control group that had also been selected for the study but were assigned to a waiting list for later treatment and were simply tested 6 weeks after their selection. The outcome study could determine whether this treatment had any benefit.

659

Why is a double-

Researchers use a range of methods to ensure that any observed effects are not due to the treatment illusions described earlier. For example, the treatment illusions caused by natural improvement and reconstructive memory happen when people compare their symptoms before treatment to their symptoms after treatment. To avoid this, a treatment (or experimental) group and a control group need to be randomly assigned to each condition and then compared at the end of treatment. That way, natural improvement or motivated reconstructive memory can’t cause illusions of effective treatment.

But what should happen to the control group during the treatment? If they simply stay home waiting until they can get treatment later (a wait-

Which Treatments Work?

How do psychologists know which treatments work and which might be harmful?

The distinguished psychologist Hans Eysenck (1916–1997) reviewed the relatively few studies of psychotherapy effectiveness available in 1957 and raised a furor among therapists by concluding that psychotherapy—

One of the most enduring debates in clinical psychology concerns how the various psychotherapies compare to one another. Some psychologists have argued for years that evidence supports the conclusion that most psychotherapies work about equally well. In this view, common factors shared by all forms of psychotherapy, such as contact with and empathy from a professional, contribute to change (Luborsky et al., 2002; Luborsky & Singer, 1975). In contrast, others have argued that there are important differences among therapies and that certain treatments are more effective than others, especially for treating particular types of problems (Beutler, 2002; Hunsley & Di Giulio, 2002). How can we make sense of these differing perspectives?

660

In 1995, the American Psychological Association (APA) published one of the first attempts to define criteria for determining whether a particular type of psychotherapy is effective for a particular problem (Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures, 1995). The official criteria for empirically validated treatments defined two levels of empirical support: well-

| Disorder | Treatment | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Depression | CBT | PT = meds; PT+meds > either alone |

| Panic disorder | CBT | PT > meds at follow- PT = meds at end of treatment; both > placebo |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | CBT | PT > present- |

| Tourette’s disorder | Habit reversal training | PT > supportive therapy |

| Insomnia | CBT | PT > medication or placebo |

| Depression and physical health in Alzheimer’s patients | Exercise and behavioral management | PT > routine medical care |

| Gulf War Veterans’ illnesses | CBT and exercise | PT > Usual care or alternative treatments |

| Note: CBT = cognitive behavior therapy; PT = psychological treatment; Meds = medication. | ||

| Source: Barlow et al. (2013). | ||

Some have questioned whether treatments shown to work in well-

How might psychotherapy cause harm?

Even trickier than the question of establishing whether a treatment works is whether a psychotherapy or medication might actually do harm. The dangers of drug treatment should be clear to anyone who has read a magazine ad for a drug and studied the fine print with its list of side effects, potential drug interactions, and complications. Many drugs used for psychological treatment may be addictive, creating long-

The dangers of psychotherapy are more subtle, but one is clear enough in some cases that there is actually a name for it. Iatrogenic illness is a disorder or symptom that occurs as a result of a medical or psychotherapeutic treatment itself (e.g., Boisvert & Faust, 2002). Such an illness might arise, for example, when a psychotherapist becomes convinced that a client has a disorder that in fact the client does not have. As a result, the therapist works to help the client accept that diagnosis and participate in psychotherapy to treat that disorder. Being treated for a disorder can, under certain conditions, make a person show signs of that very disorder—

661

There are cases of clients who have been influenced through hypnosis and repeated suggestions in therapy to believe that they have dissociative identity disorder (even coming to express multiple personalities) or to believe that they were subjected to traumatic events as a child and “recover” memories of such events when investigation reveals no evidence for these problems prior to therapy (Acocella, 1999; McNally, 2003; Of she & Watters, 1994). There are people who have entered therapy with a vague sense that something odd has happened to them and who emerge after hypnosis or other imagination-

Just as psychologists have created lists of treatments that work, they also have begun to establish lists of treatments that harm. The purpose of doing so is to inform other researchers, clinicians, and the public which treatments they should avoid. Many are under the impression that although every psychological treatment may not be effective, some treatment is better than no treatment. However, it turns out that a number of interventions intended to help alleviate people’s symptoms actually make them worse! Did your high school have a D.A.R.E. (Drug Abuse and Resistance Education) program? Have you heard of critical-

| Type of Treatment | Potential Harm | Source of Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| CISD | Increased risk of PTSD | RCTs |

| Scared straight | Worsening of conduct problems | RCTs |

| Boot- |

Worsening of conduct problems | Meta- |

| DARE programs | Increased use of alcohol and drugs | RCTs |

| Note. CISD = critical- |

||

| Source: Lilienfeld (2007). | ||

To regulate the potentially powerful influence of therapies, psychologists hold themselves to a set of ethical standards for the treatment of people with mental disorders (American Psychological Association, 2002). Adherence to these standards is required for membership in the American Psychological Association, and state licensing boards also monitor adherence to ethical principles in therapy. These ethical standards include (a) striving to benefit clients and taking care to do no harm; (b) establishing relationships of trust with clients; (c) promoting accuracy, honesty, and truthfulness; (d) seeking fairness in treatment and taking precautions to avoid biases; and (e) respecting the dignity and worth of all people. When people suffering from mental disorders come to psychologists for help, adhering to these guidelines is the least that psychologists can do. Ideally, in the hope of relieving this suffering, they can do much more.

Observing improvement during treatment does not necessarily mean that the treatment was effective; it might instead reflect natural improvement, nonspecific treatment effects (e.g., the placebo effect), and reconstructive memory processes.

Observing improvement during treatment does not necessarily mean that the treatment was effective; it might instead reflect natural improvement, nonspecific treatment effects (e.g., the placebo effect), and reconstructive memory processes. Treatment studies focus on both treatment outcomes and processes, using scientific research methods such as double-

Treatment studies focus on both treatment outcomes and processes, using scientific research methods such as double-blind techniques and placebo controls.  Treatments for psychological disorders are generally more effective than no treatment at all, but some are more effective than others for certain disorders, and both medication and psychotherapy have dangers that ethical practitioners must consider carefully.

Treatments for psychological disorders are generally more effective than no treatment at all, but some are more effective than others for certain disorders, and both medication and psychotherapy have dangers that ethical practitioners must consider carefully.

662