1.1 Psychology’s Roots: The Path to a Science of Mind

When the young William James interrupted his medical studies to travel in Europe during the late 1860s, he wanted to learn about human nature. But he confronted a very different situation than a similarly curious student would confront today, largely because psychology did not yet exist as an independent field of study. As James cheekily wrote, “The first lecture in psychology that I ever heard was the first I ever gave” (quoted in Perry, 1996, p. 228). Of course, that doesn’t mean no one had ever thought about human nature before. For 2,000 years, thinkers with scraggly beards and poor dental hygiene had pondered such questions, and in fact, modern psychology acknowledges its deep roots in philosophy. We will begin by examining those roots and then describe some of the early attempts to develop a scientific approach to psychology by relating the mind to the brain. Next, we’ll see how psychologists divided into different camps (or schools of thought): Structuralists tried to analyze the mind by breaking it down into its basic components, and functionalists focused on how mental abilities allow people to adapt to their environments.

Psychology’s Ancestors: The Great Philosophers

The desire to understand ourselves is not new. Greek thinkers such as Plato (428 BCE-

6

What fundamental question has puzzled philosophers for millennia?

Although few modern psychologists believe that nativism or empiricism is entirely correct, the issue of just how much “nature” and “nurture” explain any given behavior is still a matter of controversy. In some ways, it is quite amazing that ancient philosophers were able to articulate so many of the important questions in psychology and offer many excellent insights into their answers without any access to scientific evidence. Their ideas came from personal observations, intuition, and speculation. Although they were quite good at arguing with one another, they usually found it impossible to settle their disputes because their approach provided no means of testing their theories. As you will see in the Methods chapter, the ability to test a theory is the cornerstone of the scientific approach and the basis for reaching conclusions in modern psychology.

From the Brain to the Mind: The French Connection

We all know that the brain and the body are physical objects that we can see and touch and that the subjective contents of our minds—

What were early explanations for dualism?

Descartes suggested that the mind influences the body through a tiny structure near the bottom of the brain known as the pineal gland. He was largely alone in this view because other philosophers at the time either rejected his explanation or offered alternative ideas. For example, British philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) argued that the mind and body aren’t different things at all; rather, the mind is what the brain does. From Hobbes’s perspective, looking for a place in the brain where the mind meets the body is like looking for the place in a television where the picture meets the flat panel display.

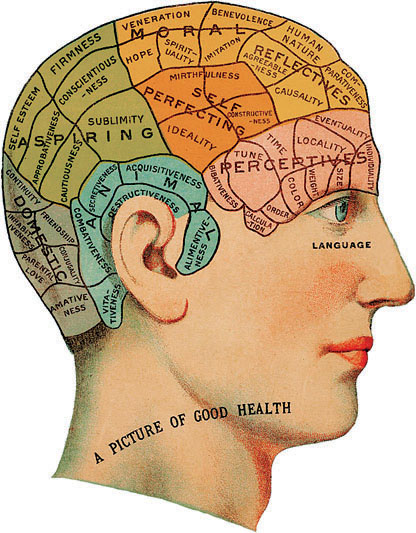

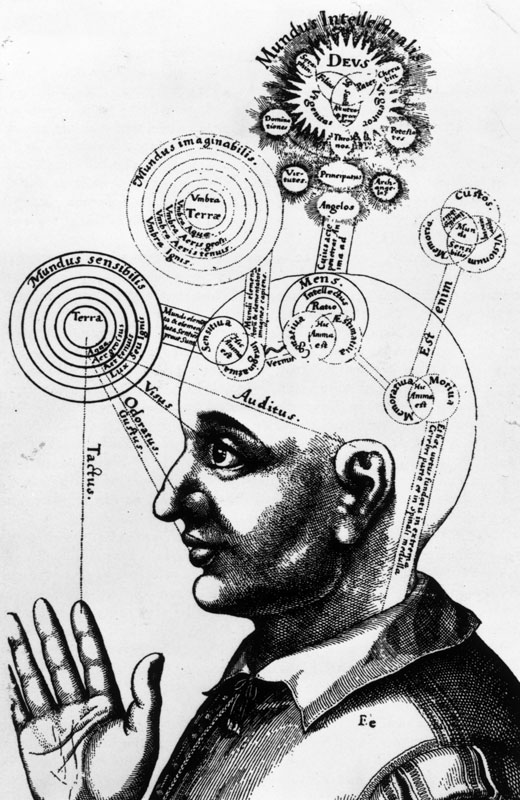

Figure 1.1: Phrenology Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828) developed a theory called phrenology, which suggested that psychological capacities (such as the capacity for friendship) and traits (such as cautiousness and mirth) were located in particular parts of the brain. The more of these capacities and traits a person had, the larger the corresponding bumps on the skull.

Figure 1.1: Phrenology Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828) developed a theory called phrenology, which suggested that psychological capacities (such as the capacity for friendship) and traits (such as cautiousness and mirth) were located in particular parts of the brain. The more of these capacities and traits a person had, the larger the corresponding bumps on the skull.

French physician Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828) also thought that brains and minds were linked, but by size rather than by glands. He examined the brains of animals and of people who had died of disease, or as healthy adults, or as children, and observed that mental ability often increases with larger brain size and decreases with damage to the brain. These aspects of Gall’s findings were generally accepted (and the part about brain damage still is today). But Gall went far beyond his evidence to develop a psychological theory known as phrenology, a now defunct theory that specific mental abilities and characteristics, ranging from memory to the capacity for happiness, are localized in specific regions of the brain (see FIGURE 1.1). The idea that different parts of the brain are specialized for specific psychological functions turned out to be right; as you’ll learn later in the book, a part of the brain called the hippocampus is intimately involved in memory, just as a structure called the amygdala is intimately involved in fear. But phrenology took this idea to an absurd extreme. Gall asserted that the size of bumps or indentations on the skull reflected the size of the brain regions beneath them and that by feeling those bumps, one could tell whether a person was friendly, cautious, assertive, idealistic, and so on. What Gall didn t realize was that bumps on the skull do not necessarily reveal anything about the shape of the brain underneath.

7

Phrenology made for a nice parlor game and gave young people a good excuse for touching each other, but in the end it amounted to a series of strong claims based on weak evidence. Not surprisingly, his critics were galled (so to speak), and they ridiculed many of his proposals. Despite an initially large following, phrenology was quickly discredited (Fancher, 1979).

While Gall was busy playing bumpologist, other French scientists were beginning to link the brain and the mind in a more convincing manner. Biologist Marie Jean Pierre Flourens (1794–1867) was appalled by Gall’s far-

How did work involving patients with brain damage help demonstrate the mind–brain connection?

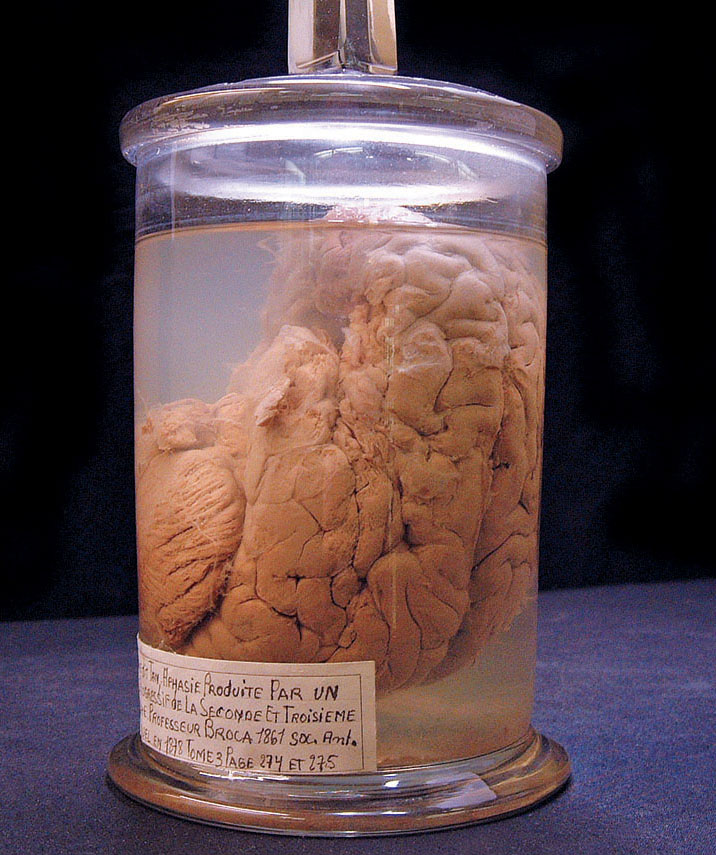

French surgeon Paul Broca (1824–1880) worked with a patient who had suffered damage to a small part of the left side of the brain (now known as Broca’s area). The patient, Monsieur Leborgne, was virtually unable to speak and could utter only the single syllable “tan.” Yet the patient understood everything that was said to him and was able to communicate using gestures. Broca had the crucial insight that damage to a specific part of the brain impaired a specific mental function, clearly demonstrating that the brain and mind are closely linked. This was important in the 19th century because at that time many people accepted Descartes’ idea that the mind is separate from, but interacts with, the brain and the body. Broca and Flourens, then, were the first to demonstrate that the mind is grounded in a material substance, namely, the brain. Their work jump-

Structuralism: Applying Methods from Physiology to Psychology

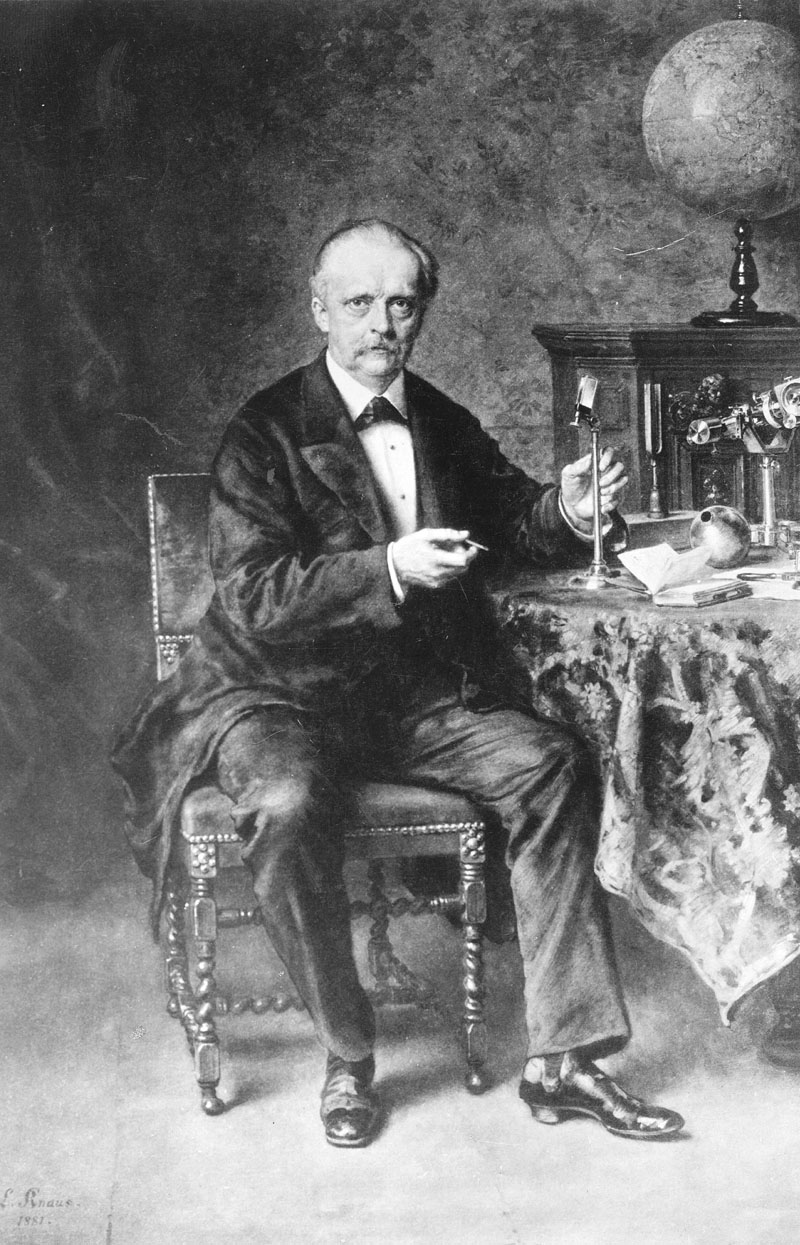

In the middle of the 19th century, psychology benefited from the work of German scientists who were trained in the field of physiology, the study of biological processes, especially in the human body. Physiologists had developed methods that allowed them to measure such things as the speed of nerve impulses, and some of them had begun to use these methods to measure mental abilities. William James was drawn to the work of two such physiologists: Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894) and Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920). “It seems to me that perhaps the time has come for psychology to begin to be a science,” wrote James in a letter written in 1867 during his visit to Berlin. “Helmholtz and a man called Wundt at Heidelberg are working at it.” What attracted James to the work of these two scientists?

8

Helmholtz Measures the Speed of Responses

What was the useful application of Hemholtz’s results?

A brilliant experimenter with a background in both physiology and physics, Helmholtz had developed a method for measuring the speed of nerve impulses in a frog’s leg, which he then adapted to the study of human beings. Helmholtz trained participants to respond when he applied a stimulus—sensory input from the environment—to different parts of the leg. He recorded his participants’ reaction time, or the amount of time taken to respond to a specific stimulus, after applying the stimulus. Helmholtz found that people generally took longer to respond when their toe was stimulated than when their thigh was stimulated, and the difference between these reaction times allowed him to estimate how long it took a nerve impulse to travel to the brain. These results were astonishing to 19th-

Wundt and the Development of Structuralism

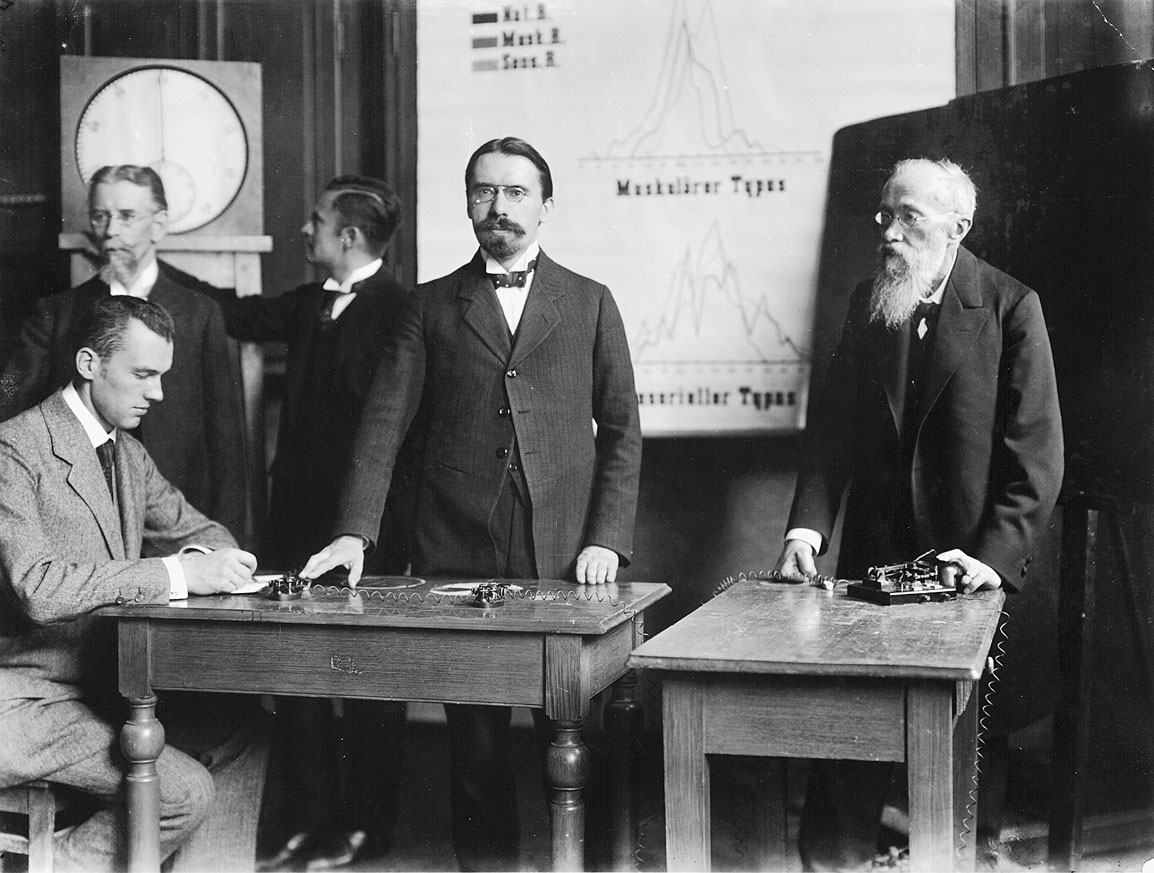

Although Helmholtz’s contributions were important, historians generally credit the official emergence of psychology to Helmholtz’s research assistant, Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920; Rieber, 1980). In 1867, at the University of Heidelberg, Wundt taught what was probably the first course in physiological psychology, which led to the publication of his book, Principles of Physiological Psychology, in 1874. Wundt called the book “an attempt to mark out [psychology] as a new domain of science” (Fancher, 1979, p. 126). In 1879, at the University of Leipzig, Wundt opened the first laboratory exclusively devoted to psychological studies, and this event marked the official birth of psychology as an independent field of study. The new lab was full of graduate students carrying out research on topics assigned by Wundt, and it soon attracted young scholars from all over the world who were eager to learn about the new science that Wundt had developed.

How did the work of chemists influence early psychology?

Wundt believed that scientific psychology should focus on analyzing consciousness, a person’s subjective experience of the world and the mind. Consciousness encompasses a broad range of subjective experiences. We may be conscious of sights, sounds, tastes, smells, bodily sensations, thoughts, or feelings. As Wundt tried to figure out a way to study consciousness scientifically, he noted that chemists try to understand the structure of matter by breaking down natural substances into basic elements. So he and his students adopted an approach called structuralism, the analysis of the basic elements that constitute the mind. This approach involved breaking down consciousness into elemental sensations and feelings, and you can do a bit of structuralism right now without leaving your chair.

Consider the contents of your own consciousness. At this very moment you may be aware of the meaning of these words, the visual appearance of the letters on the page, the key ring pressing uncomfortably against your thigh, your feelings of excitement or boredom (probably excitement), the smell of curried chicken salad, or the nagging question of whether the War of 1812 really deserves its own overture. At any given moment, all sorts of things are swimming in the stream of consciousness, and Wundt tried to analyze them in a systematic way using the method of introspection, the subjective observation of one’s own experience. In a typical experiment, observers (usually students) were presented with a stimulus (usually a color or a sound) and then asked to report their introspections. The observers described the brightness of a color or the loudness of a tone. They reported on their “raw” sensory experience, rather than on their interpretations of that experience. For example, an observer presented with this page would not report seeing words on the page (which counts as an interpretation of the experience), but instead might describe a series of black marks, some straight and others curved, against a bright white background. Wundt also attempted to carefully describe the feelings associated with elementary perceptions. For example, when Wundt listened to the clicks produced by a metronome, some of the patterns of sounds were more pleasant than others. By analyzing the relation between feelings and perceptual sensations, Wundt and his students hoped to uncover the basic structure of conscious experience.

9

Wundt tried to provide objective measurements of conscious processes by using reaction time techniques similar to those first developed by Helmholtz. Wundt used reaction times to examine a distinction between the perception and interpretation of a stimulus. His research participants were instructed to press a button as soon as a tone sounded. Some participants were told to concentrate on perceiving the tone before pressing the button, whereas others were told to concentrate only on pressing the button. Those people who concentrated on the tone responded about one tenth of a second more slowly than those told to concentrate only on pressing the button. Wundt reasoned that both fast and slow participants had to register the tone in consciousness (perception), but only the slower participants also had to interpret the significance of the tone and press the button. The faster research participants, focusing only on the response they were to make, could respond automatically to the tone because they didn’t have to engage in the additional step of interpretation (Fancher, 1979). This type of experimentation broke new ground by showing that psychologists could use scientific techniques to disentangle even subtle conscious processes. In fact, as you’ll see in later chapters, reaction time procedures have proven extremely useful in modern research.

Titchener Brings Structuralism to the United States

The pioneering efforts of Wundt’s laboratory launched psychology as an independent science and profoundly influenced the field for the remainder of the 19th century. Many European and American psychologists journeyed to Leipzig to study with Wundt. Among the most eminent was British-

10

What are the problems with the introspective method?

The influence of the structuralist approach gradually faded, due mostly to the introspective method. Science requires replicable observations; we could never determine the structure of DNA or the life span of a dust mite if every scientist who looked through a microscope saw something different. Alas, even trained observers provided conflicting introspections about their conscious experiences (“I see a cloud that looks like a duck”—“No, I think that cloud looks like a horse”), thus making it difficult for different psychologists to agree on the basic elements of conscious experience. Indeed, some psychologists had doubts about whether it was even possible to identify such elements through introspection alone. One of the most prominent skeptics was someone you’ve already met: a young man with a bad attitude and a useless medical degree named William James.

James and the Functional Approach

James returned from his European tour inspired by the idea of approaching psychological issues from a scientific perspective. He received a teaching appointment at Harvard (primarily because the president of the university was a neighbor and family friend) and his position at Harvard enabled him to purchase laboratory equipment for classroom experiments. As a result, James taught the first course at an American university to draw on the new experimental psychology developed by Wundt and his German followers (Schultz & Schultz, 1987).

THE REAL WORLD: Improving Study Skills

To get the most out of taking this course, you should begin by doing something that might seem a bit strange: make it hard on yourself. But by making it hard on yourself in the right way, you will end up making the course easier and take away a lot more from it than you would otherwise. What do we mean by making it hard on yourself? Our minds don’t work like video cameras, passively recording everything that happens and then faithfully storing the information. In order to retain new information, you need to take an active role in learning, by doing such things as rehearsing, interpreting, and testing yourself. These activities initially might seem difficult, but in fact they are what psychologists call desirable difficulties (Bjork & Bjork, 2011): making it more difficult by actively engaging during critical phases of learning will increase your retention and ultimately result in improved performance. Here are some specific suggestions:

Rehearse. One useful type of active manipulation is rehearsal: repeating to-

be- learned information to yourself. Psychologists have found that a particularly effective strategy is called spaced rehearsal, where you repeat information to yourself at increasingly long intervals. For example, suppose that you want to learn the name of a person you’ve just met named Eric. Repeat the name to yourself right away, wait a few seconds and think of it again, wait a bit longer (maybe 30 seconds) and bring the name to mind once more, then rehearse the name again after a minute and once more after 2 or 3 minutes. Making rehearsal gradually more difficult will improve retention; studies show that this type of rehearsal improves long- term learning more than rehearsing the name without any spacing between rehearsals (Landauer & Bjork, 1978). You can apply this technique to names, dates, definitions, and many other kinds of information, including concepts presented in this textbook.  Anxious feelings about an upcoming exam may be unpleasant, but as you’ve probably experienced yourself, they can motivate much-

Anxious feelings about an upcoming exam may be unpleasant, but as you’ve probably experienced yourself, they can motivate much-needed study. SUPERSTUDIO/GETTY IMAGESInterpret. Simple rehearsal can be beneficial, but one of the most important lessons from psychological research is that we acquire information most effectively when we think about its meaning and reflect on its significance. In fact, we don’t even have to try to remember something if we think deeply enough about what we want to remember; the act of reflection itself will virtually guarantee good memory. For example, suppose that you want to learn the basic ideas behind Skinner’s approach to behaviorism. Ask yourself the following kinds of questions: How did behaviorism differ from previous approaches in psychology? How would a behaviorist like Skinner think about psychological issues that interest you, such as whether a mentally disturbed individual should be held responsible for committing a crime, or what factors would contribute to your choice of a major subject or career path? In attempting to answer such questions, you will need to review what you’ve learned about behaviorism and then relate it to other things you already know about. This may seem like a demanding activity, but it is much easier to remember new information when you can relate it to something you already know. The Critical Thinking questions that are sprinkled throughout the text will help you to reflect on and interpret the material, and a happy consequence of that activity is that you will be more likely to remember the information that the questions engage you to think about.

Build. Think about and review the information you have acquired in class on a regular basis. Begin soon after class, and then try to schedule regular “booster” sessions. Don’t wait until the last second to cram your review into one sitting; as discussed in the Rehearse section, research shows that spacing out review and repetition leads to longer-

lasting recall. Test. Don’t just look at your class notes or this textbook; test yourself on the material as often as you can. As you will learn in the Memory and Learning chapters, research also shows that actively testing yourself on information you’ve acquired helps you to later remember that information more than just looking at it again. Testing yourself can also guard against a common pitfall. You may think that you have learned the material because it seems familiar to you after having reviewed it several times, but just because the material seems familiar, that doesn’t necessarily mean that you have learned it well enough to answer a test question. Testing yourself will alert you to when you need to study more, even when the information seems familiar. The Cue Questions that you will encounter throughout the text (highlighted by green question marks, as you’ll see just below this box) are designed to test you and thereby increase learning and retention. Be sure to use them. The Learning Curve study aid will also help you to test and learn (see the Preface for further discussion of Learning Curve).

Hit the main points. Take some of the load off your memory by developing effective note-

taking and outlining skills. Students often scribble down vague and fragmentary notes during lectures, figuring that the notes will be good enough to jog memory later. But when the time comes to study, they’ve forgotten so much that their notes are no longer clear. Realize that you can’t write down everything an instructor says, and try to focus on making detailed notes about the main ideas, facts, and people mentioned in the lecture. Organize. The act of organizing an outline in a way that clearly highlights the major concepts will force you to reflect on the information in a way that promotes retention and will also provide you with a helpful study guide to promote self-

testing and review. Again, this activity may seem difficult or demanding at first, but it will result in improved retention and ultimately will make learning easier for you. Sleep on it. We’ve stressed the importance of making it hard on yourself, but this final item is an easy one: get some sleep. As you’ll learn in the Hot Science box in the Memory chapter, research shows that sleep helps to form lasting memories. In fact, research shows that sleep does a particularly good job of increasing memory for important, meaningful material. So be sure to enlist sleep as an ally in studying and test preparation.

11

How does functionalism relate to Darwin’s theory of natural selection?

James agreed with Wundt on some points, including the importance of focusing on immediate experience and the usefulness of introspection as a technique (Bjork, 1983), but he disagreed with Wundt’s claim that consciousness could be broken down into separate elements. James believed that trying to isolate and analyze a particular moment of consciousness (as the structuralists did) distorted the essential nature of consciousness. Consciousness, he argued, was more like a flowing stream than a bundle of separate elements. So James decided to approach psychology from a different perspective entirely and developed an approach known as functionalism, the study of the purpose mental processes serve in enabling people to adapt to their environment. In contrast to structuralism, which examined the structure of mental processes, functionalism set out to understand the functions those mental processes served. (See the Real World box for some strategies to enhance one of those functions—

James’s thinking was inspired by the ideas in Charles Darwin’s (1809–1882) recently published book on biological evolution, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (1859). Darwin proposed the principle of natural selection: The features of an organism that help it survive and reproduce are more likely than other features to be passed on to subsequent generations. From this perspective, James reasoned, mental abilities must have evolved because they were adaptive, that is, because they helped people solve problems and increased their chances of survival. Like other animals, people have always needed to avoid predators, locate food, build shelters, and attract mates. Applying Darwin’s principle of natural selection, James (1890) reasoned that consciousness must serve an important biological function and the task for psychologists was to understand what those functions are. Wundt and the other structuralists worked in laboratories, and James believed that such work was limited in its ability to tell us how consciousness functioned in the natural environment. Wundt, in turn, believed that James did not focus enough on new findings from the laboratory that he and the structuralists had begun to produce. Commenting on The Principles of Psychology, Wundt conceded that James was a topflight writer but disapproved of his approach: “It is literature, it is beautiful, but it is not psychology” (Bjork, 1983, p. 12).

12

The rest of the world did not agree, and James’s functionalist psychology quickly gained followers, especially in North America, where Darwin’s ideas were influencing many thinkers. G. Stanley Hall (1844–1924), who studied with both Wundt and James, set up the first psychology research laboratory in North America at Johns Hopkins University in 1881. Hall’s work focused on development and education and was strongly influenced by evolutionary thinking (Schultz & Schultz, 1987).

Hall believed that, as children develop, they pass through stages that repeat the evolutionary history of the human race. Thus, the mental capacities of a young child resemble those of our ancient ancestors, and children grow over a lifetime in the same way that a species evolves over aeons. Hall founded the American Journal of Psychology in 1887 (the first psychology journal in the United States), and went on to play a key role in founding the American Psychological Association (the first national organization of psychologists in the United States), serving as its first president.

The efforts of James and Hall set the stage for functionalism to develop as a major school of psychological thought in North America. Psychology departments that embraced a functionalist approach started to spring up at many major American universities, and in a struggle for survival that would have made Darwin proud, functionalism became more influential than structuralism had ever been. By the 1920s, functionalism was the dominant approach to psychology in North America.

Philosophers have pondered and debated ideas about human nature for millennia, but given the nature of their approach, they did not provide empirical evidence to support their claims.

Philosophers have pondered and debated ideas about human nature for millennia, but given the nature of their approach, they did not provide empirical evidence to support their claims. Some of the earliest successful efforts to develop a science linking mind and behavior came from the French scientists Marie Jean Pierre Flourens and Paul Broca, who showed that damage to the brain can result in impairments of behavior and mental functions.

Some of the earliest successful efforts to develop a science linking mind and behavior came from the French scientists Marie Jean Pierre Flourens and Paul Broca, who showed that damage to the brain can result in impairments of behavior and mental functions. Hermann von Helmholtz furthered the science of the mind by developing methods for measuring reaction time.

Hermann von Helmholtz furthered the science of the mind by developing methods for measuring reaction time. Wilhelm Wundt is credited with the founding of psychology as a scientific discipline. His structuralist approach focused on analyzing the basic elements of consciousness. Wundt’s student, Edward Titchener, brought structuralism to the United States.

Wilhelm Wundt is credited with the founding of psychology as a scientific discipline. His structuralist approach focused on analyzing the basic elements of consciousness. Wundt’s student, Edward Titchener, brought structuralism to the United States. William James applied Darwin’s theory of natural selection to the study of the mind. His functionalist approach focused on how mental processes serve to enable people to adapt to their environments.

William James applied Darwin’s theory of natural selection to the study of the mind. His functionalist approach focused on how mental processes serve to enable people to adapt to their environments. G. Stanley Hall established the first American research laboratory, journal, and professional organization devoted to psychology.

G. Stanley Hall established the first American research laboratory, journal, and professional organization devoted to psychology.

13