5.2 Sleep and Dreaming: Good Night, Mind

Why are dreams considered an altered state of consciousness?

What’s it like to be asleep? Sometimes it’s like nothing at all. Sleep can produce a state of unconsciousness in which the mind and brain apparently turn off the functions that create experience: The theater in your mind is closed. But this is an oversimplification because the theater actually seems to reopen during the night for special shows of bizarre cult films—

Sleep

Consider a typical night. As you begin to fall asleep, the busy, task-

Sleep Cycle

The sequence of events that occurs during a night of sleep is part of one of the major rhythms of human life, the cycle of sleep and waking. This circadian rhythm is a naturally occurring 24-

The sleep cycle is far more than a simple on—

194

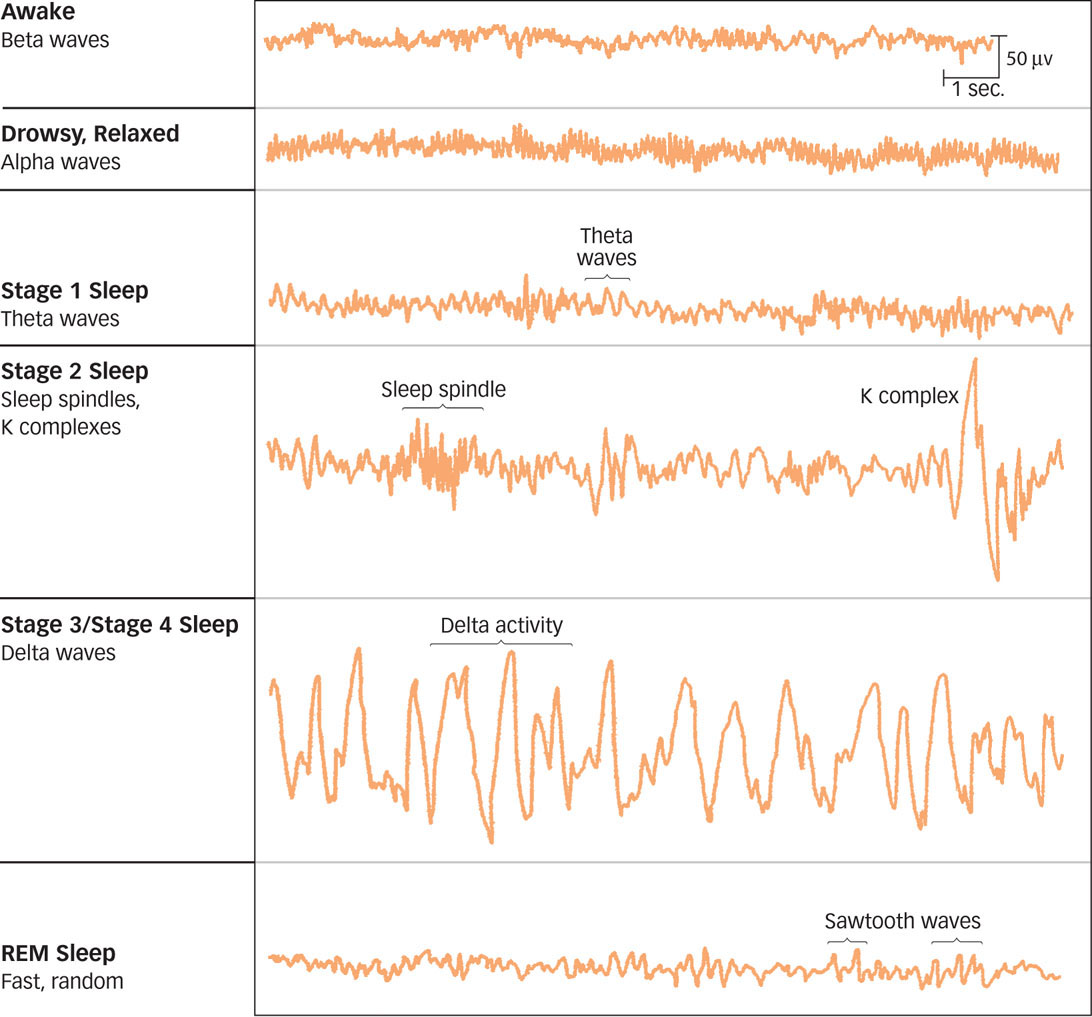

The largest changes in EEG occur during sleep. These changes show a regular pattern over the course of the night that allowed sleep researchers to identify five sleep stages (see FIGURE 5.9). In the first stage of sleep, the EEG moves to frequency patterns even lower than alpha waves (theta waves). In the second stage of sleep, these patterns are interrupted by short bursts of activity called sleep spindles and K complexes, and the sleeper becomes somewhat more difficult to awaken. The deepest stages of sleep are stages 3 and 4, known as slow-

Figure 5.9: EEG Patterns during the Stages of Sleep The waking brain shows high-

Figure 5.9: EEG Patterns during the Stages of Sleep The waking brain shows high-What do EEG recordings tell us about sleep?

During the fifth sleep stage, REM sleep, a stage of sleep characterized by rapid eye movements and a high level of brain activity, EEG patterns become high-

195

Although many people believe that they don’t dream much (if at all), some 80% of people awakened during REM sleep report dreams. If you’ve ever wondered whether dreams actually take place in an instant or whether they take as long to happen as the events they portray might take, the analysis of REM sleep offers an answer. Sleep researchers William Dement and Nathaniel Kleitman (1957) woke volunteers either 5 minutes or 15 minutes after the onset of REM sleep and asked them to judge, on the basis of the events in the remembered dream, how long they had been dreaming. Sleepers in 92 of 111 cases were correct, suggesting that dreaming occurs in “real time.” The discovery of REM sleep has offered many insights into dreaming, but not all dreams occur in REM periods. Some dreams are also reported in other sleep stages, but not as many—

What are the stages in a typical night’s sleep?

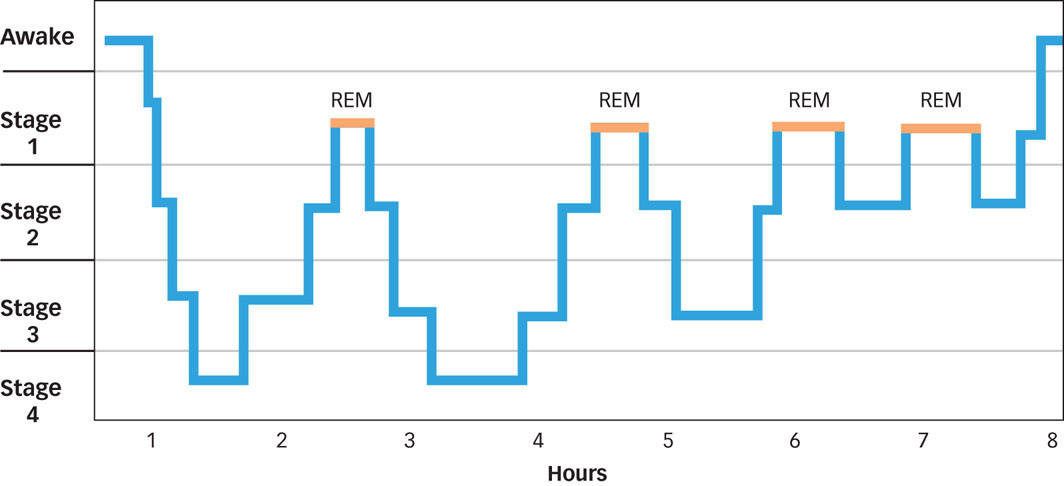

Putting EEG and REM data together produces a picture of how a typical night’s sleep progresses through cycles of sleep stages (see FIGURE 5.10). In the first hour of the night, you fall all the way from waking to the fourth and deepest stage of sleep, the stage marked by delta waves. These slow waves indicate a general synchronization of neural firing, as though the brain is doing one thing at this time rather than many: the neuronal equivalent of “the wave” moving through the crowd at a stadium as lots of individuals move together in synchrony. You then return to lighter sleep stages, eventually reaching REM and dreamland. Note that although REM sleep is lighter than that of lower stages, it is deep enough that you may be difficult to awaken. You then continue to cycle between REM and slow-

Figure 5.10: Stages of Sleep during the Night Over the course of the typical night, sleep cycles into deeper stages early on and then more shallow stages later. REM periods become longer in later cycles, and the deeper slow-

Figure 5.10: Stages of Sleep during the Night Over the course of the typical night, sleep cycles into deeper stages early on and then more shallow stages later. REM periods become longer in later cycles, and the deeper slow-196

Sleep Needs and Deprivation

How much do people sleep? The answer depends on the age of the sleeper (Dement, 1999). Newborns will sleep 6 to 8 times in 24 hours, often totaling more than 16 hours. Their napping cycle gets consolidated into “sleeping through the night,” usually sometime between 9 and 18 months, but occasionally even later. The typical 6-

This is a lot of sleeping. Could we tolerate less? Monitored by William Dement, Randy Gardner stayed up for 264 hours and 12 minutes in 1965 for a science project. When 17-

What is the relationship between sleep and learning?

Feats like this one suggest that sleep might be expendable. This is the theory behind the classic all-

Sleep turns out to be a necessity rather than a luxury in other ways as well. At the extreme, sleep loss can be fatal. When rats are forced to break Randy Gardner’s human waking record and stay awake even longer, they have trouble regulating their body temperature and lose weight although they eat much more than normal. Their bodily systems break down and they die, on average, in 21 days (Rechtshaffen et al., 1983). Shakespeare called sleep “nature’s soft nurse,” and it is clear that even for healthy young humans, a few hours of sleep deprivation each night can have a cumulative detrimental effect: reducing mental acuity and reaction time, increasing irritability and depression, and increasing the risk of accidents and injury (Coren, 1997).

Some studies have deprived people of different sleep stages selectively by waking them whenever certain stages are detected. Studies of REM sleep deprivation indicate that this part of sleep is important psychologically. Memory problems and excessive aggression are observed in both humans and rats after only a few days of being wakened whenever REM activity starts (Ellman et al., 1991). The brain must value something about REM sleep because REM deprivation causes a rebound of more REM sleep the next night (Brunner et al., 1990). Deprivation from slow-

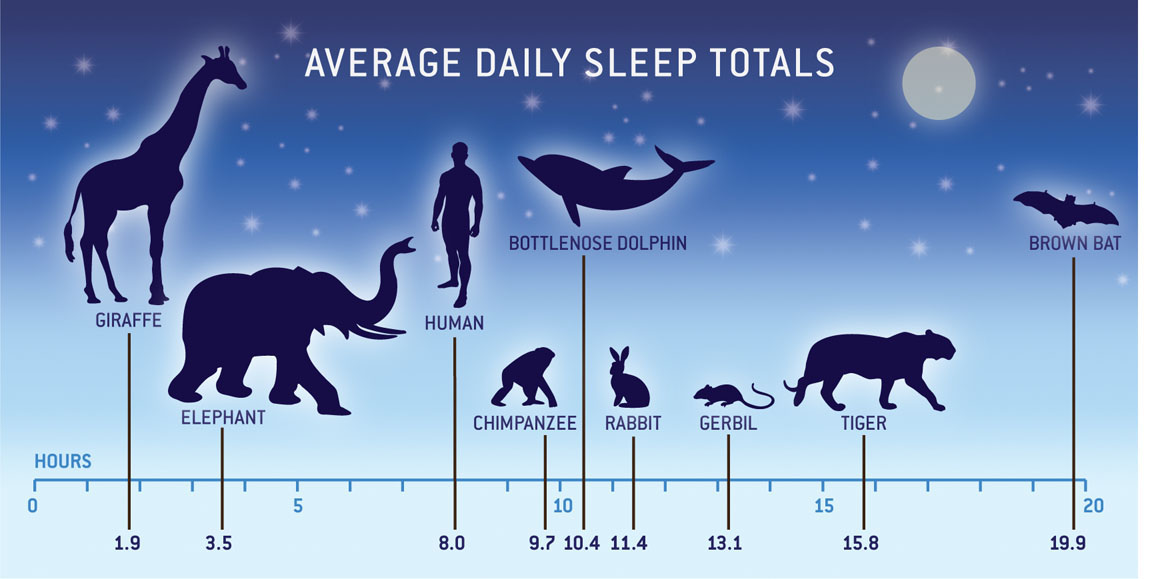

It’s clearly dangerous to neglect the need for sleep. But why would we have such a need in the first place? All animals appear to sleep, although the amount of sleep required varies quite a bit (see FIGURE 5.11). Giraffes sleep less than 2 hours daily, whereas brown bats snooze for almost 20 hours. These variations in sleep needs, and the very existence of a need, are hard to explain. Is the restoration that happens during the unconsciousness of sleep something that simply can’t be achieved during consciousness? Sleep is, after all, potentially costly in the course of evolution. The sleeping animal is easy prey, so the habit of sleep would not seem to have developed so widely across species unless it had significant benefits that made up for this vulnerability. Theories of sleep have not yet determined why the brain and body have evolved to need these recurring episodes of unconsciousness.

Figure 5.11: All animals and insects seem to require sleep, although in differing amounts. Next time you oversleep and someone accuses you of “sleeping like a baby,” you might tell them that instead that you were sleeping like a tiger, or a brown bat.

Figure 5.11: All animals and insects seem to require sleep, although in differing amounts. Next time you oversleep and someone accuses you of “sleeping like a baby,” you might tell them that instead that you were sleeping like a tiger, or a brown bat.

197

Sleep Disorders

In answer to the question, “Did you sleep well?,” comedian Stephen Wright said, “No, I made a couple of mistakes.” Sleeping well is something everyone would love to do, but for many people, sleep disorders are deeply troubling. The most common disorders that plague sleep include insomnia, sleep apnea, and somnambulism.

Insomnia, difficulty in falling asleep or staying asleep, is perhaps the most common sleep disorder. About 30–48% of people report symptoms of insomnia, 9–15% report insomnia severe enough to lead to daytime complaints, and 6% of people meet criteria for a diagnosis of insomnia, which requires persistent and impairing sleep problems (Bootzin & Epstein, 2011; Ohayon, 2002). Unfortunately, insomnia often is a persistent problem and most people with insomnia experience it for at least a year (Morin et al., 2009).

There are many potential causes of insomnia. In some instances it results from lifestyle choices such as working night shifts (self-

What are some problems caused by sleeping pills?

Giving up on trying so hard to sleep is probably better than another common remedy—

198

Sleep apnea is a disorder in which the person stops breathing for brief periods while asleep. A person with apnea usually snores because apnea involves an involuntary obstruction of the breathing passage. When episodes of apnea occur for over 10 seconds at a time and recur many times during the night, they may cause many awakenings and sleep loss or insomnia. Apnea occurs most often in middle-

Is it safe to wake a sleepwalker?

Somnambulism (or sleepwalking), occurs when a person arises and walks around while asleep. Sleepwalking is more common in children, peaking between the ages of 4 and 8 years, with 15–40% of children experiencing at least one episode (Bhargava, 2011). Sleepwalking tends to happen early in the night, usually in slow-

There are other sleep disorders that are less common. Narcolepsy is a disorder in which sudden sleep attacks occur in the middle of waking activities. Narcolepsy involves the intrusion of a dreaming state of sleep (with REM) into waking and is often accompanied by unrelenting excessive sleepiness and uncontrollable sleep attacks lasting from 30 seconds to 30 minutes. This disorder appears to have a genetic basis, as it runs in families, and can be treated effectively with medication. Sleep paralysis is the experience of waking up unable to move and is sometimes associated with narcolepsy. This eerie experience usually happens as you are awakening from REM sleep but before you have regained motor control. This period typically lasts only a few seconds or minutes and can be accompanied by hypnopompic (when awakening) or hypnagogic (when falling asleep) hallucinations in which dream content may appear to occur in the waking world. A very clever series of recent studies suggests that sleep paralysis accompanied by hypnopompic hallucinations of figures being in one’s bedroom seems to explain many perceived instances of alien abductions and recovered memories of sexual abuse (aided by therapists who used hypnosis to help the sleepers [incorrectly] piece it all together; McNally & Clancy, 2005). Night terrors (or sleep terrors) are abrupt awakenings with panic and intense emotional arousal. These terrors, which occur most often in children and in only about 2% of adults (Ohayon, Guilleminault, & Priest, 1999), happen most often in non-

199

To sum up, there is a lot going on when we close our eyes for the night. Humans follow a pretty regular sleep cycle, going through the five stages of sleep during the night. Disruptions to that cycle, either from sleep deprivation or sleep disorders, can produce consequences for waking consciousness. But something else happens during a night’s sleep that affects our consciousness, both while asleep and when we wake up.

Dreams

Pioneering sleep researcher William C. Dement (1959) said, “Dreaming permits each and every one of us to be quietly and safely insane every night of our lives.” Indeed, dreams do seem to have a touch of insanity about them. We experience crazy things in dreams, but even more bizarre is the fact that we are the writers, producers, and directors of the crazy things we experience. Just what are these experiences, and how can they be explained?

Dream Consciousness

What distinguishes dream consciousness from the waking state?

Dreams depart dramatically from reality. You may dream of being naked in public, of falling from a great height, of sleeping through an important appointment, of your teeth being loose and falling out, or of being chased (Holloway, 2001). These things don’t happen much in reality unless you’re having a very bad life. The quality of consciousness in dreaming is also altered significantly from waking consciousness. There are five major characteristics of dream consciousness that distinguish it from the waking state (Hobson, 1988).

We intensely feel emotion, whether it is bliss or terror or love or awe.

We intensely feel emotion, whether it is bliss or terror or love or awe. Dream thought is illogical: The continuities of time, place, and person don’t apply. You may find you are in one place and then another, for example, without any travel in between—

Dream thought is illogical: The continuities of time, place, and person don’t apply. You may find you are in one place and then another, for example, without any travel in between—or people may change identity from one dream scene to the next.  Sensation is fully formed and meaningful; visual sensation is predominant, and you may also deeply experience sound, touch, and movement (although pain is very uncommon).

Sensation is fully formed and meaningful; visual sensation is predominant, and you may also deeply experience sound, touch, and movement (although pain is very uncommon). Dreaming occurs with uncritical acceptance, as though the images and events are perfectly normal rather than bizarre.

Dreaming occurs with uncritical acceptance, as though the images and events are perfectly normal rather than bizarre. We have difficulty remembering the dream after it is over. People often remember dreams only if they are awakened during the dream and even then may lose recall for the dream within just a few minutes of waking. If waking memory were this bad, you’d be standing around half-

We have difficulty remembering the dream after it is over. People often remember dreams only if they are awakened during the dream and even then may lose recall for the dream within just a few minutes of waking. If waking memory were this bad, you’d be standing around half-naked in the street much of the time, having forgotten your destination, clothes, and lunch money.

Not all of our dreams are fantastic and surreal, however. Far from the adventures in nighttime insanity storied by Freud, dreams are often ordinary (Domhoff, 2007). We often dream about mundane topics that reflect prior waking experiences or “day residue.” Current conscious concerns pop up (Nikles et al., 1998), along with images from the recent past. A dream may even incorporate sensations experienced during sleep, as when sleepers in one study were led to dream of water when drops were sprayed on their faces during REM sleep (Dement & Wolpert, 1958). The day residue does not usually include episodic memories, that is, complete daytime events replayed in the mind. Rather, dreams that reflect the day’s experience tend to single out sensory experiences or objects from waking life. Rather than simply being a replay of that event, dreams often consist of “interleaved fragments of experience” from different times and places that our mind weaves together into a single story (Wamsley & Stickgold, 2011). For instance, after a fun day at the beach with your roommates, your dream that night might include cameo appearances by bouncing beach balls or a flock of seagulls. One study had research participants play the computer game Tetris and found that participants often reported dreaming about the Tetris geometrical figures falling down—

200

Some of the most memorable dreams are nightmares, and these frightening dreams can wake up the dreamer (Levin & Nielsen, 2009). One set of daily dream logs from college undergraduates suggested that the average student has about 24 nightmares per year (Wood & Bootzin, 1990), although some people may have them as often as every night. Children have more nightmares than adults, and people who have experienced traumatic events are inclined to have nightmares that relive those events. Following the 1989 earthquake in the San Francisco Bay area, for example, college students who had experienced the quake reported more nightmares than those who had not and often reported that the dreams were about the quake (Wood et al., 1992). This effect of trauma may not only produce dreams of the traumatic event: When police officers experience “critical incidents” of conflict and danger, they tend to have more nightmares in general (Neylan et al., 2002).

Dream Theories

Dreams are puzzles that cry out to be solved. How could you not want to make sense out of these experiences? Although dreams may be fantastic and confusing, they are emotionally riveting, filled with vivid images from your own life, and they seem very real. The search for dream meaning goes all the way back to biblical figures, who interpreted dreams and looked for prophecies in them. In the Old Testament, the prophet Daniel (a favorite of three of the authors of this book) curried favor with King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon by interpreting the king’s dream. The question of what dreams mean has been burning since antiquity, mainly because the meaning of dreams is usually far from obvious.

In the first psychological theory of dreams, Freud (1900/1965) proposed that dreams are confusing and obscure because the dynamic unconscious creates them precisely to be confusing and obscure. According to Freud’s theory, dreams represent wishes, and some of these wishes are so unacceptable, taboo, and anxiety producing that the mind can only express them in disguised form. Freud believed that many of the most unacceptable wishes are sexual. For instance, he would interpret a dream of a train going into a tunnel as symbolic of sexual intercourse. According to Freud, the manifest content of a dream, a dream’s apparent topic or superficial meaning, is a smoke screen for its latent content, a dream’s true underlying meaning. For example, a dream about a tree burning down in the park across the street from where a friend once lived (the manifest content) might represent a camouflaged wish for the death of the friend (the latent content). In this case, wishing for the death of a friend is unacceptable, so it is disguised as a tree on fire. The problem with Freud’s approach is that there is an infinite number of potential interpretations of any dream and finding the correct one is a matter of guesswork—

201

What is the evidence that we dream about our suppressed thoughts?

Although dreams may not represent elaborately hidden wishes, there is evidence that they do feature the return of suppressed thoughts. Researchers asked volunteers to think of a personal acquaintance and then to spend five minutes before going to bed writing down whatever came to mind (Wegner, Wenzlaff, & Kozak, 2004). Some participants were asked to suppress thoughts of this person as they wrote, others were asked to focus on thoughts of the person, and yet others were asked just to write freely about anything. The next morning, participants wrote dream reports. Overall, all participants mentioned dreaming more about the person they had named than about other people. But they most often dreamed of the person they named if they were in the group that had been assigned to suppress thoughts of the person the night before. This finding suggests that Freud was right to suspect that dreams harbor unwanted thoughts. Perhaps this is why actors dream of forgetting their lines, travelers dream of getting lost, and football players dream of fumbling the ball.

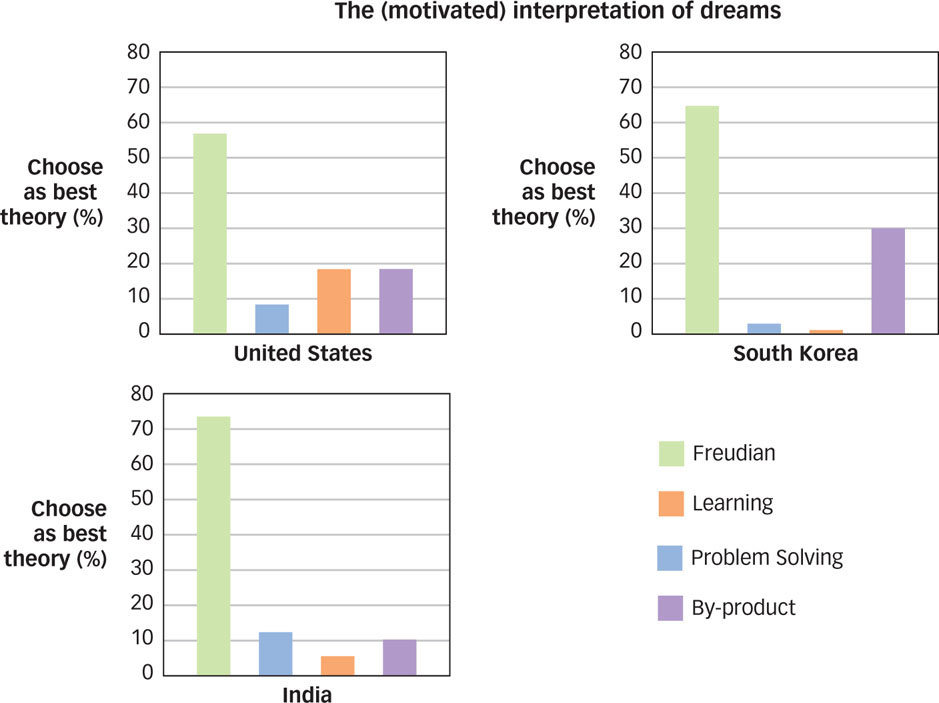

CULTURE & COMMUNITY: What Do Dreams Mean to Us around the World?

A recent study (Morewedge & Norton, 2009) assessed how people from three different cultures evaluate their dreams. Participants were asked to rate different theories of dreaming on a scale of 1 (do not agree at all) to 7 (agree completely). A significant majority of students from the United States, South Korea, and India agreed with the Freudian theory that dreams have meanings. Only small percentages believed the other options, that dreams provide a means to solve problems, promote learning, or are by-

Another key theory of dreaming is the activation-synthesis model (Hobson & McCarley, 1977). This theory proposes that dreams are produced when the brain attempts to make sense of random neural activity that occurs during sleep. During waking consciousness, the mind is devoted to interpreting lots of information that arrives through the senses. You figure out that the odd noise you’re hearing during class is your cell phone vibrating, for example, or you realize that the strange smell in the hall outside your room must be from burned popcorn. In the dream state, the mind doesn’t have access to external sensations, but it keeps on doing what it usually does: interpreting information. Because that information now comes from neural activations that occur without the continuity provided by the perception of reality, the brain’s interpretive mechanisms can run free. This might be why, for example, a person in a dream can sometimes change into someone else. There is no actual person being perceived to help the mind keep a stable view. In the mind’s effort to perceive and give meaning to brain activation, the person you view in a dream about a grocery store might seem to be a clerk but then change to be your favorite teacher when the dream scene moves to your school. The great interest people have in interpreting their dreams the next morning may be an extension of the interpretive activity they’ve been doing all night.

202

The Freudian theory and the activation—

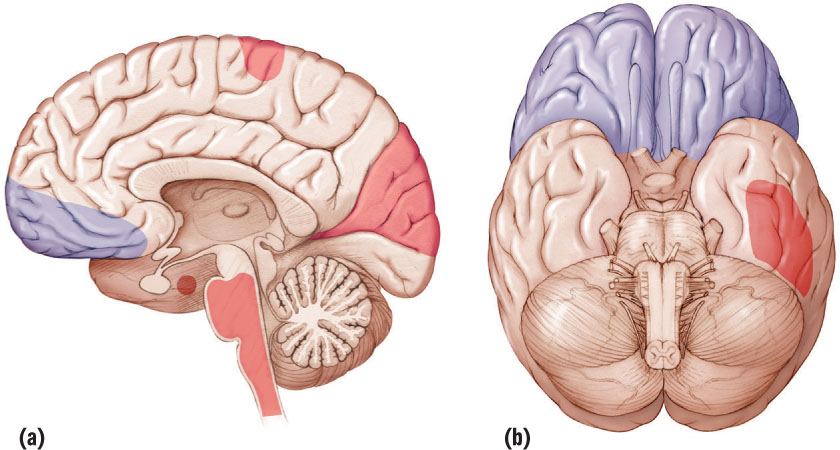

The Dreaming Brain

What happens in the brain when we dream? Several studies have made fMRI scans of people’s brains during sleep, focusing on the areas of the brain that show changes in activation during REM periods. These studies show that the brain changes that occur during REM sleep correspond clearly with certain alterations of consciousness that occur in dreaming. FIGURE 5.12 shows some of the patterns of activation and deactivation found in the dreaming brain (Nir & Tononi, 2010; Schwartz & Maquet, 2002).

Figure 5.12: Brain Activation and Deactivation during REM Sleep Brain areas shaded red are activated during REM sleep; those shaded blue are deactivated. (a) The medial view shows activation of the amygdala, the visual association areas, the motor cortex, and the brain stem and deactivation of the prefrontal cortex. (b) The ventral view shows activation of other visual association areas and deactivation of the prefrontal cortex (Schwartz & Maquet, 2002).

Figure 5.12: Brain Activation and Deactivation during REM Sleep Brain areas shaded red are activated during REM sleep; those shaded blue are deactivated. (a) The medial view shows activation of the amygdala, the visual association areas, the motor cortex, and the brain stem and deactivation of the prefrontal cortex. (b) The ventral view shows activation of other visual association areas and deactivation of the prefrontal cortex (Schwartz & Maquet, 2002).

In dreams there are heights to look down from, dangerous people lurking, the occasional monster, some minor worries, and at least once in a while that major exam you’ve forgotten about until you walk into class. These themes suggest that the brain areas responsible for fear or emotion somehow work overtime in dreams, and it turns out that this is clearly visible in fMRI scans. The amygdala is involved in responses to threatening or stressful events, and indeed the amygdala is quite active during REM sleep.

203

The typical dream is also a visual wonderland, with visual events present in almost all dreams. However, there are fewer auditory sensations, even fewer tactile sensations, and almost no smells or tastes. This dream “picture show” doesn’t involve actual perception, of course, just the imagination of visual events. It turns out that the areas of the brain responsible for visual perception are not activated during dreaming, whereas the visual association areas in the occipital lobe that are responsible for visual imagery do show activation (Braun et al., 1998). Your brain is smart enough to realize that it’s not really seeing bizarre images but acts instead as though it’s imagining bizarre images.

What do fMRIs tell us about why dreams don’t have coherent story lines?

During REM sleep, the prefrontal cortex shows relatively less arousal than it usually does during waking consciousness. What does this mean for the dreamer? As a rule, the prefrontal areas are associated with planning and executing actions, and often dreams seem to be unplanned and rambling. Perhaps this is why dreams often don’t have very sensible story lines—

Another odd fact of dreaming is that while the eyes are moving rapidly, the body is otherwise very still. During REM sleep, the motor cortex is activated, but spinal neurons running through the brain stem inhibit the expression of this motor activation (Lai & Siegal, 1999). This turns out to be a useful property of brain activation in dreaming; otherwise, you might get up and act out every dream! Individuals suffering from one rare sleep disorder, in fact, lose the normal muscular inhibition accompanying REM sleep and so act out their dreams, thrashing around in bed or stalking around the bedroom (Mahowald & Schenck, 2000). However, most people who are moving during sleep are probably not dreaming. The brain specifically inhibits movement during dreams, perhaps to keep us from hurting ourselves.

Sleeping and dreaming present a view of the mind in an altered state of consciousness.

Sleeping and dreaming present a view of the mind in an altered state of consciousness. During a night’s sleep, the brain passes in and out of five stages of sleep; most dreaming occurs in the REM sleep stage.

During a night’s sleep, the brain passes in and out of five stages of sleep; most dreaming occurs in the REM sleep stage. Sleep needs decrease over the life span, but being deprived of sleep and dreams has psychological and physical costs.

Sleep needs decrease over the life span, but being deprived of sleep and dreams has psychological and physical costs. Sleep can be disrupted through disorders that include insomnia, sleep apnea, somnambulism, narcolepsy, sleep paralysis, and night terrors.

Sleep can be disrupted through disorders that include insomnia, sleep apnea, somnambulism, narcolepsy, sleep paralysis, and night terrors. In dreaming, the dreamer uncritically accepts changes in emotion, thought, and sensation but poorly remembers the dream on awakening.

In dreaming, the dreamer uncritically accepts changes in emotion, thought, and sensation but poorly remembers the dream on awakening. Theories of dreaming include Freud’s psychoanalytic theory and the activation-

Theories of dreaming include Freud’s psychoanalytic theory and the activation-synthesis model.  fMRI studies of the brain in dreaming reveal activations associated with visual imagery, reductions of other sensations, increased sensitivity to emotions such as fear, lessened capacities for planning, and the prevention of movement.

fMRI studies of the brain in dreaming reveal activations associated with visual imagery, reductions of other sensations, increased sensitivity to emotions such as fear, lessened capacities for planning, and the prevention of movement.

204