5.3 Drugs and Consciousness: Artificial Inspiration

The author of the dystopian novel Brave New World, Aldous Huxley (1932), once wrote of his experiences with the drug mescaline. The Doors of Perception described the intense experience that accompanied his departure from normal consciousness. He described “a world where everything shone with the Inner Light, and was infinite in its significance. The legs, for example, of a chair—

Being the legs of a chair? This probably is better than being the seat of a chair, but it still sounds like an odd experience. Still, many people seek out such experiences, often through using drugs. Psychoactive drugs are chemicals that influence consciousness or behavior by altering the brain’s chemical message system. You read about several such drugs in the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter when we explored the brain’s system of neurotransmitters. And you will read about them in a different light when we turn to their role in the treatment of psychological disorders in the Treatment chapter. Whether these drugs are used for entertainment, for treatment, or for other reasons, they each exert their influence by increasing the activity of a neurotransmitter (the agonists) or decreasing its activity (the antagonists).

Some of the most common neurotransmitters are serotonin, dopamine, gammaaminobutyric acid (GABA), and acetylcholine. Drugs alter the functioning of neurotransmitters by preventing them from bonding to sites on the postsynaptic neuron, by inhibiting their reuptake to the presynaptic neuron, or by enhancing their bonding and transmission. Different drugs can intensify or dull transmission patterns, creating changes in brain electrical activities that mimic natural operations of the brain. For example, a drug such as Valium (benzodiazepine) induces sleep but prevents dreaming and so creates a state similar to slow-

Drug Use and Abuse

Why do children sometimes spin around until they get dizzy and fall down? There is something strangely attractive about states of consciousness that depart from the norm, and people throughout history have sought out these altered states by dancing, fasting, chanting, meditating, and ingesting a bizarre assortment of chemicals to intoxicate themselves (Tart, 1969). People pursue altered consciousness even when there are costs, from the nausea that accompanies dizziness to the life-

What is the allure of altered consciousness?

Often, drug-

205

Rats are not tiny little humans, of course, so such research is not a firm basis for understanding human responses to cocaine. But these results do make it clear that cocaine is addictive and that the consequences of such addiction can be dire. Studies of self-

People usually do not become addicted to a psychoactive drug the first time they use it. They may experiment a few times, then try again, and eventually find that their tendency to use the drug increases over time due to several factors, such as drug tolerance, physical dependence, and psychological dependence. Drug tolerance is the tendency for larger drug doses to be required over time to achieve the same effect. Physicians who prescribe morphine to control pain in their patients are faced with tolerance problems because steadily greater amounts of the drug may be needed to dampen the same pain. With increased tolerance comes the danger of drug overdose; recreational users find they need to use more and more of a drug to produce the same high. But then, if a new batch of heroin or cocaine is more concentrated than usual, the “normal” amount the user takes to achieve the same high can be fatal.

What problems I can arise in drug withdrawal?

Self-

Drug addiction reveals a human frailty: our inability to look past the immediate consequences of our behavior to see and appreciate the long-

206

What are the statistics on overcoming addiction?

The psychological and social problems stemming from drug addiction are major. For many people, drug addiction becomes a way of life, and for some, it is a cause of death. Like the cocaine-

It may not be accurate to view all recreational drug use under the umbrella of “addiction.” Many people at this point in the history of Western society, for example, would not call the repeated use of caffeine an addiction, and some do not label the use of alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana in this way. In other times and places, however, each of these has been considered a terrifying addiction worthy of prohibition and public censure. In the early 17th century, for example, tobacco use was punishable by death in Germany, by castration in Russia, and by decapitation in China (Corti, 1931). Not a good time to be a smoker. By contrast, cocaine, heroin, marijuana, and amphetamines have each been popular and even recommended as medicines at several points throughout history, each without any stigma of addiction attached (Inciardi, 2001).

Although “addiction” as a concept is familiar to most of us, there is no standard clinical definition of what an addiction actually is. The concept of addiction has been extended to many human pursuits, giving rise to such terms as sex addict, gambling addict, workaholic, and, of course, chocoholic. Societies react differently at different times, with some uses of drugs ignored, other uses encouraged, others simply taxed, and yet others subjected to intense prohibition (see the Real World box on p. 212). Rather than viewing all drug use as a problem, it is important to consider the costs and benefits of such use and to establish ways to help people choose behaviors that are informed by this knowledge (Parrott et al., 2005).

207

Types of Psychoactive Drugs

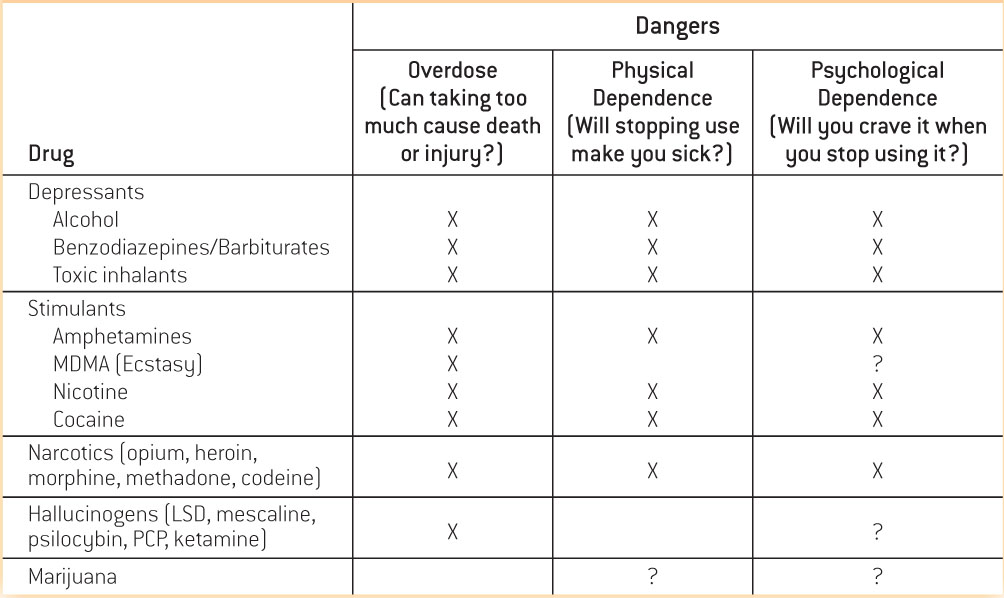

Four in five North Americans use caffeine in some form every day, but not all psychoactive drugs are this familiar. To learn how both the well-

Depressants

Depressants are substances that reduce the activity of the central nervous system. The most commonly used depressant is alcohol, and others include barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and toxic inhalants (such as glue or gasoline). Depressants have a sedative or calming effect, tend to induce sleep in high doses, and can arrest breathing in extremely high doses. Depressants can produce both physical and psychological dependence.

Alcohol. Alcohol is king of the depressants, with its worldwide use beginning in prehistory, its easy availability in most cultures, and its widespread acceptance as a socially approved substance. Fifty-

Why do people experience being drunk differently?

Alcohol’s initial effects, euphoria and reduced anxiety, feel pretty positive. As it is consumed in greater quantities, drunkenness results, bringing slowed reactions, slurred speech, poor judgment, and other reductions in the effectiveness of thought and action. The exact way in which alcohol influences neural mechanisms is still not understood, but like other depressants, alcohol increases activity of the neurotransmitter GABA (De Witte, 1996). As you read in the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter, GABA normally inhibits the transmission of neural impulses, and so one effect of alcohol is as an inhibitor—

208

Expectancy theory suggests that alcohol effects can be produced by people’s expectations of how alcohol will influence them in particular situations (Marlatt & Rohsenow, 1980). So, for instance, if you’ve watched friends or family drink at weddings and notice that this often produces hilarity and gregariousness, you could well experience these effects yourself should you drink alcohol on a similarly festive occasion. Seeing people getting drunk and fighting in bars, in turn, might lead to aggression after drinking.

The expectancy theory has been tested in studies that examine the effects of actual alcohol ingestion independent of the perception of alcohol ingestion. In experiments using a balanced placebo design, behavior is observed following the presence or absence of an actual stimulus and also following the presence or absence of a placebo stimulus. In such a study, participants are given drinks containing alcohol or a substitute liquid, and some people in each group are led to believe they had alcohol and others are led to believe they did not. People told they are drinking alcohol when they are not, for instance, might get a touch of vodka on the plastic lid of a cup to give it the right odor when the drink inside is merely tonic water. These experiments often show that the belief that one has had alcohol can influence behavior as strongly as the ingestion of alcohol itself (Goldman, Brown, & Christiansen, 1987). You may have seen people at parties getting rowdy after only one beer—

Another approach to the varied effects of alcohol is the theory of alcohol myopia, which proposes that alcohol hampers attention, leading people to respond in simple ways to complex situations (Steele & Josephs, 1990). This theory recognizes that life is filled with complicated pushes and pulls, and our behavior is often a balancing act. Imagine that you are really attracted to someone who is dating your friend. Do you make your feelings known or focus on your friendship? The myopia theory holds that when you drink alcohol, your fine judgment is impaired. It becomes hard to appreciate the subtlety of these different options, and the inappropriate response is to veer full tilt one way or the other. So, alcohol might lead you to make a wild pass at your friend’s date or perhaps just cry in your beer over your timidity—

In one study on the alcohol myopia theory, men (half of whom were drinking alcohol) watched a video showing an unfriendly woman and then were asked how acceptable it would be for a man to act sexually aggressive toward a woman (Johnson, Noel, & Sutter-

Both the expectancy and myopia theories suggest that people using alcohol will often go to extremes (Cooper, 2006). In fact, it seems that drinking is a major contributing factor to social problems that result from extreme behavior. Drinking while driving is a main cause of auto accidents. Twenty-

209

Barbiturates, Benzodiazepines, and Toxic Inhalants. Compared to alcohol, the other depressants are much less popular but still are widely used and abused. Barbiturates such as Seconal or Nembutal are prescribed as sleep aids and as anesthetics before surgery. Benzodiazepines such as Valium and Xanax are also called minor tranquilizers and are prescribed as antianxiety drugs. These drugs are prescribed by physicians to treat anxiety or sleep problems, but they are dangerous when used in combination with alcohol because they can cause respiratory depression. Physical dependence is possible because withdrawal from long-

Stimulants

Do stimulants create dependency?

Stimulants are substances that excite the central nervous system, heightening arousal and activity levels. They include caffeine, amphetamines, nicotine, cocaine, modafinil, and Ecstasy, and sometimes have a legitimate pharmaceutical purpose. Amphetamines (also called speed), for example, were originally prepared for medicinal uses and as diet drugs; however, amphetamines such as Methedrine and Dexedrine are widely abused, causing insomnia, aggression, and paranoia with long-

Ecstasy (also known as MDMA, “X,” or “E”), an amphetamine derivative, is a stimulant but it has added effects somewhat like those of hallucinogens (we’ll talk about those shortly). Ecstasy is particularly known for making users feel empathic and close to those around them. It is used often as a party drug to enhance the group feeling at dance clubs or raves, but it has unpleasant side effects such as causing jaw clenching and interfering with the regulation of body temperature. The rave culture has popularized pacifiers and juices as remedies for these problems, but users remain highly susceptible to heatstroke and exhaustion. Although Ecstasy is not as likely as some other drugs to cause physical or psychological dependence, it nonetheless can lead to some dependence. What’s more, the impurities sometimes found in street pills are also dangerous (Parrott, 2001). Ecstasy’s potentially toxic effect on serotonin neurons in the human brain is under debate, although mounting evidence from animal and human studies suggests that sustained use is associated with damage to serotonergic neurons and potentially associated problems with mood, attention and memory, and impulse control (Kish et al., 2010; Urban et al., 2012).

210

What are some of the dangerous side effects of cocaine use?

Cocaine is derived from leaves of the coca plant, which has been cultivated by indigenous peoples of the Andes for millennia and chewed as a medication. Yes, the urban legend is true: Coca-

Nicotine is something of a puzzle. This is a drug with almost nothing to recommend it to the newcomer. It usually involves inhaling smoke that doesn’t smell that great, at least at first, and there’s not much in the way of a high either—

Narcotics

Why are narcotics especially alluring?

Opium, which comes from poppy seeds, and its derivatives heroin, morphine, methadone, and codeine (as well as prescription drugs such as Demerol and Oxycontin), are known as narcotics (or opiates), highly addictive drugs derived from opium that relieve pain. Narcotics induce a feeling of well-

The brain produces endogenous opioids or endorphins, which are neurotransmitters closely related to opiates. As you learned in the Neuroscience & Behavior chapter, endorphins play a role in how the brain copes internally with pain and stress. These substances reduce the experience of pain naturally. When you exercise for a while and start to feel your muscles burning, for example, you may also find that there comes a time when the pain eases—

211

Hallucinogens

The drugs that produce the most extreme alterations of consciousness are the hallucinogens, drugs that alter sensation and perception, and often cause visual and auditory hallucinations. These include LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide, or acid), mescaline, psilocybin, PCP (phencyclidine), and ketamine (an animal anesthetic). Some of these drugs are derived from plants (mescaline from peyote cactus, psilocybin or “shrooms” from mushrooms) and have been used by people since ancient times. For example, the ingestion of peyote plays a prominent role in some Native American religious practices. The other hallucinogens are largely synthetic. LSD was first made by chemist Albert Hofman in 1938, leading to a rash of experimentation that influenced popular culture in the 1960s. Timothy Leary, at the time a lecturer in the Department of Psychology at Harvard, championed the use of LSD to “turn on, tune in, and drop out”; the Beatles sang of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” (denying, of course, that this might be a reference to LSD); and the wave of interest led many people to experiment with hallucinogens.

What are the effects of hallucinogens?

The experiment was not a great success. These drugs produce profound changes in perception. Sensations may seem unusually intense, stationary objects may seem to move or change, patterns or colors may appear, and these perceptions may be accompanied by exaggerated emotions ranging from blissful transcendence to abject terror. These are the “I’ve-

Marijuana

Marijuana (or cannabis) is a plant whose leaves and buds contain a psychoactive drug called tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). When smoked or eaten, either as is or in concentrated form as hashish, this drug produces an intoxication that is mildly hallucinogenic. Users describe the experience as euphoric, with heightened senses of sight and sound and the perception of a rush of ideas. Marijuana affects judgment and short-

What are the risks of marijuana use?

The addiction potential of marijuana is not strong, as tolerance does not seem to develop, and physical withdrawal symptoms are minimal. Psychological dependence is possible, however, and some people do become chronic users. Marijuana use has been widespread throughout the world for recorded history, both as a medicine for pain and/or nausea and as a recreational drug, but its use remains controversial. Marijuana abuse and dependence have been linked with increased risk of depression, anxiety, and other forms of psychopathology. Many people also are concerned that marijuana (along with alcohol and tobacco) is a gateway drug, a drug whose use increases the risk of the subsequent use of more harmful drugs. The gateway theory has gained mixed support, with recent studies challenging this theory and suggesting that early-

212

THE REAL WORLD: Drugs and the Regulation of Consciousness

Everyone has an opinion about drug use. Given that it’s not possible to perceive what happens in anyone else’s mind, why does it matter to us what people do to their own consciousness? Is consciousness something that governments should be able to legislate? Or should people be free to choose their own conscious states (McWilliams, 1993)? After all, how can a “free society” justify regulating what people do inside their own heads?

Individuals and governments alike answer these questions by pointing to the costs of drug addiction, both to the addict and to the society that must “carry” unproductive people, pay for their welfare, and often even take care of their children. Drug users appear to be troublemakers and criminals, the culprits behind all those drug-

Drug use did not stop with 40 years of the War on Drugs though, and instead, prisons filled with people arrested for drug use. From 1990 to 2007, the number of drug offenders in state and federal prisons increased from 179,070 to 348,736—

213

What can be done? The policy of the Obama administration is to wind down the war mentality and instead focus on reducing the harm that drugs cause (Fields, 2009). This harm reduction approach is a response to high-

There appears to be increasing support for the idea that people should be free to decide whether they want to use substances to alter their consciousness, especially when use of the substance carries a medical benefit, such as decreased nausea, decreased insomnia, and increased appetite. Since 1996, 18 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws to legalize the use of marijuana for medical purposes. On November 6, 2012, Colorado and Washington became the first two states to legalize marijuana for purely recreational purposes. The fact that marijuana continues to be a Schedule I Controlled Substance under federal law complicates matters and it may take years before the legal issues involved are fully resolved. Indeed, upon learning of the passing of the legalization initiative, Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper warned citizens of Colorado: “Federal law still says marijuana is an illegal drug so don’t break out the Cheetos or Goldfish too quickly.”

Psychoactive drugs influence consciousness by altering the brain’s chemical messaging system and intensifying or dulling the effects of neurotransmitters.

Psychoactive drugs influence consciousness by altering the brain’s chemical messaging system and intensifying or dulling the effects of neurotransmitters. Drug tolerance can result in overdose, and physical and psychological dependence can lead to addiction.

Drug tolerance can result in overdose, and physical and psychological dependence can lead to addiction. Major types of psychoactive drugs include depressants, stimulants, narcotics, hallucinogens, and marijuana.

Major types of psychoactive drugs include depressants, stimulants, narcotics, hallucinogens, and marijuana. The varying effects of alcohol, a depressant, are explained by theories of alcohol expectancy and alcohol myopia.

The varying effects of alcohol, a depressant, are explained by theories of alcohol expectancy and alcohol myopia.

214