9.3 Language and Thought: How Are They Related?

Language is such a dominant feature of our mental world that it is tempting to equate language with thought. Some theorists have even argued that language is simply a means of expressing thought. The linguistic relativity hypothesis maintains that language shapes the nature of thought. This idea was championed by Benjamin Whorf (1956), an engineer who studied language in his spare time and was especially interested in Native American languages. The most frequently cited example of linguistic relativity comes from the Inuit in Canada. Their language has many different terms for frozen white flakes of precipitation, for which we use the word snow. Whorf believed that because they have so many terms for snow, the Inuit perceive and think about snow differently than do English speakers.

Language and Color Processing

How does language influence our understanding of color?

Whorf has been criticized for the anecdotal nature of his observations (Pinker, 1994), and some controlled research has cast doubt on Whorf’s hypothesis. Eleanor Rosch (1973) studied the Dani, an isolated agricultural tribe living in New Guinea. They have only two terms for colors that roughly refer to “dark” and “light.” If Whorf’s hypothesis were correct, you would expect the Dani to have problems perceiving and learning different shades of color. But in Rosch’s experiments, they learned shades of color just as well as people who have many more color terms in their first language. However, more recent evidence shows that language may indeed influence color processing (Roberson et al., 2004). Researchers compared English children with African children from a cattle-

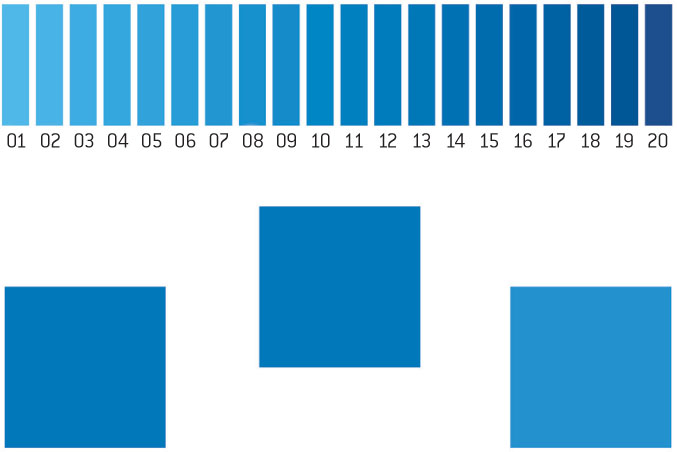

Figure 9.5: Language Affects How We Think About Color Unlike English, the Russian language has different words for light blue and dark blue. Russian speakers asked to pick which of the two bottom squares matched the color of the single square above responded more quickly when one of the bottom squares was called goluboy (light blue) and the other was called siniy (dark blue) than when both were referred to by the same name. English speakers took about the same amount of time.

Figure 9.5: Language Affects How We Think About Color Unlike English, the Russian language has different words for light blue and dark blue. Russian speakers asked to pick which of the two bottom squares matched the color of the single square above responded more quickly when one of the bottom squares was called goluboy (light blue) and the other was called siniy (dark blue) than when both were referred to by the same name. English speakers took about the same amount of time.

Researchers showed a series of colored tiles to each child and then asked the child to choose that color from an array of 22 different colors. The youngest children, both English and Himba, who knew few or no color names, tended to confuse similar colors. But as the children grew and acquired more names for colors, their choices increasingly reflected the color terms they had learned. English children made fewer errors matching tiles that had English color names; Himba children made fewer errors for tiles with color names in Himba. These results reveal that language can indeed influence how children think about colors.

Similar effects have been observed in adults. Consider the 20 blue rectangles shown in FIGURE 9.5, which you’ll easily see change gradually from lightest blue on the left to darkest blue on the right. What you might not know is that in Russian, there are different words for light blue (goluboy) and dark blue (siniy). Researchers investigated whether Russian speakers would respond differently to patches of blue when they fell into different linguistic categories rather than into the same linguistic category (Winawer et al., 2007). Both Russian and English speakers on average classified rectangles 1–8 as light blue and 9–20 as dark blue, but only Russian speakers use different words to refer to the two classes of blue. In the experimental task, participants were shown three blue squares, as in the lower part of Figure 9.5, and were asked to pick which of the two bottom squares matched the colors of the top square. Russian speakers responded more quickly when one of the bottom squares was goluboy and the other was siniy than when both bottom squares were goluboy or both were siniy, whereas English speakers took about the same amount of time to respond in the two conditions (Winawer et al., 2007). As with children, language can affect how adults think about colors.

368

Language and the Concept of Time

How does a horizontal concept of time contrast with a vertical concept of time?

In another study exploring the relationship between language and thought, researchers looked at the way people think about time. In English, we often use spatial terms: We look forward to a promising future or move a meeting back to fit our schedule (Casasanto & Boroditsky, 2008). We also use these terms to describe horizontal spatial relations, such as taking three steps forward or two steps back (Boroditsky, 2001). In contrast, speakers of Mandarin (Chinese) often describe time using terms that refer to a vertical spatial dimension: Earlier events are referred to as up, and later events as down. To test the effect of this difference, researchers showed English speakers and Mandarin speakers either a horizontal or vertical display of objects and then asked them to make a judgment involving time, such as whether March comes before April (Boroditsky, 2001). English speakers were faster to make the time judgments after seeing a horizontal display, whereas for Mandarin speakers the opposite was true. When English speakers learned to use Mandarin spatial terms, their time judgments were also faster after seeing the vertical display! This result nicely shows another way in which language can influence thought.

Bear in mind, though, that either thought or language ability can be severely impaired while the capacity for the other is spared, as illustrated by the dramatic case of Christopher that you read earlier in this chapter–and as we’ll see again in the next section. These kinds of observations have led some researchers to suggest that Whorf was only “half right” in his claims about the effect of language on thought (Regier & Kay, 2009). Consistent with this idea, others suggest that it is overly simplistic to talk in general terms about whether language influences thought, and that researchers need to be more specific about the exact ways in which language influences thought. For example, Wolff & Holmes (2011) rejected the idea that language entirely determines thought. But they also pointed out that there is considerable evidence that language can influence thought both by highlighting specific properties of concepts and by allowing us to formulate verbal rules that help to solve problems. Thus, recent research has started to clarify the ways in which the linguistic relativity hypothesis is right and the ways in which it is wrong.

The linguistic relativity hypothesis maintains that language shapes the nature of thought.

The linguistic relativity hypothesis maintains that language shapes the nature of thought. Recent studies on color processing and time judgments point to an influence of language on thought. However, it is also clear that language and thought are to some extent separate.

Recent studies on color processing and time judgments point to an influence of language on thought. However, it is also clear that language and thought are to some extent separate.

369