6.5 Memory Failures: The Seven Sins of Memory

You probably have not given much thought to breathing today, and the reason is that from the moment you woke up, you have been doing it effortlessly and well. But the moment breathing fails, you are reminded of just how important it is. Memory is like that. Every time we see, think, notice, imagine, or wonder, we are drawing on our ability to use information stored in our brains, but it is not until this ability fails that we become acutely aware of just how much we should treasure it. We have seen in other contexts how an understanding of foibles and errors of human thought and action reveals the normal operation of various behaviours. Such memory errors—

6.5.1 1. Transience

Wilder Penfield was a famous Canadian neurosurgeon who founded the Montreal Neurological Institute and developed the effective surgical treatment of epilepsy. Before operating on a patient, he would stimulate regions of their brain with electrical probes. This was done while the patient was awake on the operating table (under local anaesthesia). His intent was to identify the regions of the brain responsible for generating the seizures, but in the process he was able to create detailed maps of the function of the human cortex. Stimulation in one area would cause the left hand to twitch. Stimulation in another area would cause the patient to report a tingling in their right leg. Many of the experiences reported by patients after stimulation had the character of amazingly detailed, vivid memories. For example, a patient might hear the voice of a cousin in Africa, or see a man and dog walking along a road near his place in the country. During such experiences, the patient was simultaneously aware of being in the operating room. These “memories” (as they seemed to be) were so detailed that, to Penfield, it seemed as though the cortex must contain a permanent record of all past experience. In fact, only a small minority of his patients reported such experiences, and whether or not they are memories is impossible to know—

Transience occurs during the storage phase of memory, after an experience has been encoded and before it is retrieved. You have already seen the workings of transience—

Figure 6.15: The Curve of Forgetting Hermann Ebbinghaus measured his retention at various delay intervals after he studied lists of nonsense syllables. Retention was measured in percent savings, that is, the percentage of time needed to relearn the list compared to the time needed to learn it initially.

Figure 6.15: The Curve of Forgetting Hermann Ebbinghaus measured his retention at various delay intervals after he studied lists of nonsense syllables. Retention was measured in percent savings, that is, the percentage of time needed to relearn the list compared to the time needed to learn it initially.

How might general memories come to distort specific memories?

Not only do we forget memories with the passage of time, the quality of our memories also changes. At early time points on the forgetting curve—

Yet another way that memories can be distorted is by interference from other memories. For example, if you carry out the same activities at work each day, by the time Friday rolls around, it may be difficult to remember what you did on Monday because later activities blend in with earlier ones. This is an example of retroactive interference, situations in which later learning impairs memory for information acquired earlier (Postman & Underwood, 1973). Proactive interference, in contrast, refers to situations in which earlier learning impairs memory for information acquired later. If you use the same parking lot each day at work or at school, you have probably gone out to find your car and then stood there confused by the memories of having parked it on previous days.

6.5.2 2. Absentmindedness

The great cellist Yo-

What makes people absentminded? One common cause is lack of attention. Attention plays a vital role in encoding information into long-

How is memory affected for someone whose attention is divided?

What happens in the brain when attention is divided? In one study, volunteers tried to learn a list of word pairs while researchers scanned their brains with positron emission tomography (PET) (Shallice et al., 1994). Some people simultaneously performed a task that took little attention (they moved a bar the same way over and over), whereas other people simultaneously performed a task that took a great deal of attention (they moved a bar over and over but in a novel, unpredictable way each time). The researchers observed less activity in the participants’ lower left frontal lobe when their attention was divided. As you saw earlier, greater activity in the lower left frontal region during encoding is associated with better memory. Dividing attention, then, prevents the lower left frontal lobe from playing its normal role in semantic encoding, and the result is absentminded forgetting. More recent research using fMRI has shown that divided attention also leads to less hippocampal involvement in encoding (Kensinger, Clarke, & Corkin, 2003; Uncapher & Rugg, 2008). Given the importance of the hippocampus to episodic memory, this finding may help to explain why absentminded forgetting is sometimes so extreme, as when we forget where we put our keys or glasses only moments earlier.

Another common cause of absentmindedness is forgetting to carry out actions that we planned to do in the future. On any given day, you need to remember the times and places that your classes meet, you need to remember with whom and where you are having lunch, you need to remember which grocery items to pick up for dinner, and you need to remember which page of this book you were on when you fell asleep. In other words, you have to remember to remember, and this is called prospective memory, remembering to do things in the future (Einstein & McDaniel, 1990, 2005).

Failures of prospective memory are a major source of absentmindedness. Avoiding these problems often requires having a cue available at the moment you need to remember to carry out an action. For example, air traffic controllers must sometimes postpone an action, such as granting a pilot’s request to change altitude, but remember to carry out that action a few minutes later when conditions change. In a simulated air traffic control experiment, researchers provided controllers with electronic signals to remind them to carry out a deferred request 1 minute later. The reminders were made available either during the 1-

6.5.3 3. Blocking

Have you ever tried to recall the name of a famous actor or a book you have read—

Studies have found that when people are in tip-

Why is Snow White’s name easier to remember than Mary Poppins?

Blocking occurs especially often for the names of people and places (Cohen, 1990; Semenza, 2009; Valentine, Brennen, & Brédart, 1996). Why? Because their links to related concepts and knowledge are weaker than for common names. That somebody’s last name is Baker does not tell us much about the person, but saying that he is a baker does. To illustrate this point, researchers showed people pictures of cartoon and comic strip characters, some with descriptive names that highlight key features of the character (e.g., Grumpy, Snow White, Scrooge) and others with arbitrary names (e.g., Aladdin, Mary Poppins, Pinocchio) (Brédart & Valentine, 1998). Even though the two types of names were equally familiar to participants in the experiment, they blocked less often on the descriptive names than on the arbitrary names.

Although it is frustrating when it occurs, blocking is a relatively infrequent event for most of us. However, it occurs more often as we grow older, and it is a very common complaint among people in their 60s and 70s (Burke et al., 1991; Schwartz, 2002). Even more striking, some individuals with brain damage live in a nearly perpetual tip-

6.5.4 4. Memory Misattribution

Figure 6.16: Memory Misattribution Another common form of memory misattribution is unintentional plagiarism: forgetting the source of an idea and assuming that you have come up with it yourself. In 1971, musician George Harrison had a huge hit worldwide with the song “My Sweet Lord.” Due to its similarity with the earlier Chiffons’ hit “He’s So Fine” (written by Ronnie Mack), Harrison was sued. In 1976 the court found that he had “subconsciously” copied the earlier song, but that the lack of awareness was not a mitigating factor–

Figure 6.16: Memory Misattribution Another common form of memory misattribution is unintentional plagiarism: forgetting the source of an idea and assuming that you have come up with it yourself. In 1971, musician George Harrison had a huge hit worldwide with the song “My Sweet Lord.” Due to its similarity with the earlier Chiffons’ hit “He’s So Fine” (written by Ronnie Mack), Harrison was sued. In 1976 the court found that he had “subconsciously” copied the earlier song, but that the lack of awareness was not a mitigating factor–Memory misattribution errors, which involve assigning a recollection or an idea to a wrong source, are some of the primary causes of eyewitness misidentifications. For example, the memory researcher Donald Thomson was accused of rape based on the victim’s detailed recollection of his face, but he was eventually cleared when it turned out he had an airtight alibi. At the time of the rape, Thomson was giving a live television interview on the subject of distorted memories! The victim had been watching the show just before she was assaulted and misattributed her memory of Thomson’s face to the rapist (Schacter, 1996; Thomson, 1988). Thomson’s case, though dramatic, is not an isolated occurrence: Faulty eyewitness memory was a factor in more than 75 percent of the first 310 American cases in which individuals were shown to be innocent by DNA evidence after conviction for crimes they did not commit (Innocence Project, 2012). See FIGURE 6.16 for another example or memory misattribution.

What can explain a déjà vu experience?

Part of memory is knowing where our memories came from. This is known as source memory, recall of when, where, and how information was acquired (Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, 1993; Mitchell & Johnson, 2009; Schacter, Harbluk, & McLachlan, 1984). People sometimes correctly recall a fact they learned earlier or accurately recognize a person or object they have seen before but misattribute the source of this knowledge—

Individuals with damage to the frontal lobes are especially prone to memory misattribution errors (Schacter et al., 1984; Shimamura & Squire, 1987). This is probably because the frontal lobes play a significant role in effortful retrieval processes, which are required to dredge up the correct source of a memory. These individuals sometimes produce bizarre misattributions. In 1991, a British photographer in his mid-

The subjective experience for M.R., as in everyday déjà vu experiences, is characterized by a strong sense of familiarity without any recall of associated details. Other individuals with neurological damage exhibit a recently discovered type of memory misattribution called déjà vécu: They feel strongly—

|

Sour |

Thread |

|

Candy |

Pin |

|

Sugar |

Eye |

|

Bitter |

Sewing |

|

Good |

Sharp |

|

Taste |

Point |

|

Tooth |

Prick |

|

Nice |

Thimble |

|

Honey |

Haystack |

|

Soda |

Pain |

|

Chocolate |

Hurt |

|

Heart |

Injection |

|

Cake |

Syringe |

|

Tart |

Cloth |

|

Pie |

Knitting |

But we are all vulnerable to memory misattribution. Take the following test and there is a good chance that you will experience false recognition for yourself. First, study the two lists of words presented in TABLE 6.1 by reading each word for about 1 second. When you are done, return to this paragraph for more instructions, but do not look back at the table! Now try to recognize which of the following words appeared on the list you just studied: taste, bread, needle, king, sweet, thread. If you think that taste and thread were on the lists you studied, you are right. And if you think that bread and king were not on those lists, you are also right. But if you think that needle or sweet appeared on the lists, you are dead wrong.

Most people make exactly the same mistake, claiming with confidence that they saw needle and sweet on the list. This occurs because all the words in the lists are associated with needle or sweet. Seeing each word in the study list activates related words. Because needle and sweet are related to all of the associates, they become more activated than other words—

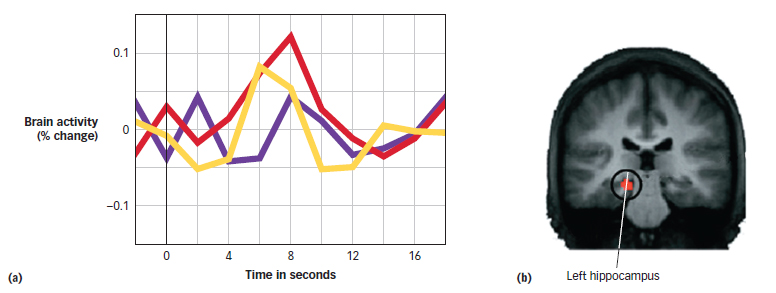

Figure 6.17: Hippocampal Activity during True and False Recognition Many brain regions show similar activation during true and false recognition, including the hippocampus. The figure shows results from an fMRI study of true and false recognition of visual shapes (Slotnick & Schacter, 2004). A plot of the activity level in the strength of the fMRI signal from the hippocampus over time (a) shows that after a few seconds, there is comparable activation for true recognition of previously studied shapes (red line) and false recognition of similar shapes that were not presented (yellow line). Both true and false recognition show increased hippocampal activity compared with correctly classifying unrelated shapes as new (purple line). The brain scan (b) shows a region of the left hippocampus.

Figure 6.17: Hippocampal Activity during True and False Recognition Many brain regions show similar activation during true and false recognition, including the hippocampus. The figure shows results from an fMRI study of true and false recognition of visual shapes (Slotnick & Schacter, 2004). A plot of the activity level in the strength of the fMRI signal from the hippocampus over time (a) shows that after a few seconds, there is comparable activation for true recognition of previously studied shapes (red line) and false recognition of similar shapes that were not presented (yellow line). Both true and false recognition show increased hippocampal activity compared with correctly classifying unrelated shapes as new (purple line). The brain scan (b) shows a region of the left hippocampus.

However, false recognition can be reduced (Schacter, Israel, & Racine, 1999). For example, recent evidence shows that when participants are given a choice between an object that they actually saw (e.g., a car) and a visually similar new object (a different car that looks like the one they saw), they almost always choose the car that they actually saw and thus avoid making a false recognition error (Guerin et al., 2012a, 2012b). This finding suggests that false recognition occurs, at least in part, because when presented with a similar new object on its own, participants do not recollect specific details about the object they actually studied, but these details need to be retrieved in order to correctly indicate that the similar object is new. Yet this information is available in memory, as shown by the ability of participants to correctly choose between the studied object and the visually similar new object. When people experience a strong sense of familiarity about a person, object, or event but lack specific recollections, a potentially dangerous recipe for memory misattribution is in place, both in the laboratory and also in real-

6.5.5 5. Suggestibility

How can eyewitnesses be mislead?

On October 4, 1992, an El Al cargo plane crashed into an apartment building in a southern suburb of Amsterdam, killing 39 residents and all 4 members of the airline crew. The disaster dominated news in the Netherlands for days as people viewed footage of the crash scene and read about the catastrophe. Ten months later, Dutch psychologists asked a simple question of university students: “Did you see the television film of the moment the plane hit the apartment building?” Fifty-

If misleading details can be implanted in people’s memories, is it also possible to suggest entire episodes that never occurred? The answer seems to be yes (Loftus, 1993, 2003). In one study, the research participant, a teenager named Chris, was asked by his older brother, Jim, to try to remember the time Chris had been lost in a shopping mall at age 5. He initially recalled nothing, but after several days, Chris produced a detailed recollection of the event. He recalled that he “felt so scared I would never see my family again” and remembered that a kindly old man wearing a flannel shirt found him crying (Loftus, 1993, p. 532). But according to Jim and other family members, Chris was never lost in a shopping mall. Of 24 participants in a larger study on implanted memories, approximately 25 percent falsely remembered being lost as a child in a shopping mall or in a similar public place (Loftus & Pickrell, 1995).

Why can childhood memories be influenced by suggestion?

People develop false memories in response to suggestions for some of the same reasons memory misattribution occurs. We do not store all the details of our experiences in memory, making us vulnerable to accepting suggestions about what might have happened or should have happened. In addition, visual imagery plays an important role in constructing false memories (Goff & Roediger, 1998). Asking people to imagine an event like spilling punch all over the bride’s parents at a wedding increases the likelihood that they will develop a false memory of it (Hyman & Pentland, 1996).

Suggestibility played an important role in a controversy that arose during the 1980s and 1990s concerning the accuracy of childhood memories that people recalled during psychotherapy. One highly publicized example involved a woman named Diana Halbrooks (Schacter, 1996). After a few months in psychotherapy, she began recalling disturbing incidents from her childhood, for example, that her mother had tried to kill her and that her father had abused her sexually. Although her parents denied that these events had ever occurred, her therapist encouraged her to believe in the reality of her memories. Eventually Diana Halbrooks stopped therapy and came to realize that the “memories” she had recovered were inaccurate.

How could this happen? A number of the techniques used by psychotherapists to try to pull up forgotten childhood memories are clearly suggestive (Poole et al., 1995). Specifically, research has shown that imagining past events and hypnosis can help create false memories (Garry et al., 1996; Hyman & Pentland, 1996; McConkey, Barnier, & Sheehan, 1998). More recent studies show that memories that people remember spontaneously on their own are corroborated by other people at about the same rate as the memories of individuals who never forgot their abuse, whereas memories recovered in response to suggestive therapeutic techniques are virtually never corroborated by others (McNally & Geraerts, 2009).

6.5.6 6. Bias

In 2000, the outcome of a very close race to decide the next American president, between George W. Bush and Al Gore, was decided by the Supreme Court 5 weeks after the election had taken place. The day after the election (when the result was still in doubt), supporters of Bush and Gore were asked to predict how happy they would be after the outcome of the election was determined (Wilson, Meyers, & Gilbert, 2003). These same respondents reported how happy they felt with the outcome on the day after Al Gore conceded. And 4 months later, the participants recalled how happy they had been right after the election was decided.

Bush supporters, who eventually enjoyed a positive result (their candidate took office), were understandably happy the day after the Supreme Court’s decision. However, their retrospective accounts overestimated how happy they were at the time. Conversely, Gore supporters were not pleased with the outcome. But when polled 4 months after the election was decided, Gore supporters underestimated how happy they actually were at the time of the result. In both groups, recollections of happiness were at odds with existing reports of their actual happiness at the time (Wilson et al., 2003).

These results illustrate the problem of bias, the distorting influences of present knowledge, beliefs, and feelings on recollection of previous experiences. Sometimes what people remember from their pasts says less about what actually happened than about what they think, feel, or believe now. Researchers have also found that our current moods can bias our recall of past experiences (Bower, 1981; Buchanan, 2007; Eich, 1995). So, in addition to helping you recall actual sad memories (as you saw earlier in this chapter), a sad mood can also bias your recollections of experiences that may not have been so sad. Consistency bias is the bias to reconstruct the past to fit the present. One researcher asked Americans in 1973 to rate their attitudes toward a variety of controversial social issues, including legalization of marijuana, women’s rights, and aid to minorities (Markus, 1986). They were asked to make the same rating again in 1982 and also to indicate what their attitudes had been in 1973. Researchers found that participants’ recollections of their 1973 attitudes in 1982 were more closely related to what they believed in 1982 than to what they had actually said in 1973.

How does your current outlook colour your memory of a past event?

Whereas consistency bias exaggerates the similarity between past and present, change bias is the tendency to exaggerate differences between what we feel or believe now and what we felt or believed in the past. In other words, change biases also occur. For example, most of us would like to believe that our romantic attachments grow stronger over time. In one study, dating couples were asked, once a year for 4 years, to assess the present quality of their relationships and to recall how they felt in past years (Sprecher, 1999). Couples who stayed together for the 4 years recalled that the strength of their love had increased since they last reported on it. Yet their actual ratings at the time did not show any increases in love and attachment. Objectively, the couples did not love each other more today than yesterday. But they did from the subjective perspective of memory.

A special case of change bias is egocentric bias, the tendency to exaggerate the change between present and past in order to make ourselves look good in retrospect. For example, students sometimes remember feeling more anxious before taking an exam than they actually reported at the time (Keuler & Safer, 1998), and blood donors sometimes recall being more nervous about giving blood than they actually were (Breckler, 1994). In both cases, change biases colour memory and make people feel that they behaved more bravely or courageously than they actually did. Similarly, when American university students tried to remember high school grades and their memories were checked against actual transcripts, they were highly accurate for grades of A (89 percent correct) and extremely inaccurate for grades of D (29 percent correct) (Bahrick, Hall, & Berger, 1996). The same kind of egocentric bias occurs with memory for college grades: 81 percent of students inflated the actual grade, and this bias was evident even when participants were asked about their grades soon after graduation (Bahrick, Hall, & DaCosta, 2008). People were remembering the past as they wanted it to be rather than the way it was.

6.5.7 7. Persistence

The artist Melinda Stickney-

Melinda Stickney-

Controlled laboratory studies have revealed that emotional experiences tend to be better remembered than nonemotional ones. For instance, memory for unpleasant pictures, such as mutilated bodies, or pleasant ones, such as attractive men and women, is more accurate than for emotionally neutral pictures, such as household objects (Ochsner, 2000). Emotional arousal seems to focus our attention on the central features of an event. In one experiment, people who viewed an emotionally arousing sequence of slides involving a bloody car accident remembered more of the central themes and fewer peripheral details than people who viewed a nonemotional sequence (Christianson & Loftus, 1987).

How does emotional trauma affect memory?

Intrusive memories are undesirable consequences of emotional experiences because emotional experiences generally lead to more vivid and enduring recollections than nonemotional experiences do. One line of evidence comes from the study of flashbulb memories, which are detailed recollections of when and where we heard about emotionally intense events (Brown & Kulik, 1977). For example, most people in North America can recall exactly where they were and how they heard about the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in which passenger aircraft were deliberately flown into the the World Trade Center in New York City—

Figure 6.18: The Amygdala’s Influence on Memory The amygdala, located next to the hippocampus, responds strongly to emotional events. Individuals with amygdala damage are unable to remember emotional events any better than nonemotional ones (Cahill & McGaugh, 1998).

Figure 6.18: The Amygdala’s Influence on Memory The amygdala, located next to the hippocampus, responds strongly to emotional events. Individuals with amygdala damage are unable to remember emotional events any better than nonemotional ones (Cahill & McGaugh, 1998).

Why do our brains succumb to persistence? A key player in the brain’s response to emotional events is a small, almond-

For example, consider what happened when people viewed a series of photographic slides that began with a mother walking her child to school and later included an emotionally arousing event: the child being hit by a car. When tested later, the research participants remembered the arousing event better than the mundane ones. But individuals with amygdala damage remembered the mundane and emotionally arousing events equally well (Cahill & McGaugh, 1998). PET and fMRI scans show that when healthy people view a slide sequence that includes an emotionally arousing event, the level of activity in the amygdala at the time they see it is a good predictor of their subsequent memory for the slide. When there is heightened activity in the amygdala as people watch emotional events, there is a better chance that they will recall those events on a later test (Cahill et al., 1996; Kensinger & Schacter, 2005, 2006). And when people are given a drug that interferes with the amygdala-

In many cases, there are clear benefits to forming strong memories for highly emotional events, particularly those that are life-

6.5.8 Are the Seven Sins Vices or Virtues?

You may have concluded that evolution has burdened us with an extremely inefficient memory system that is so prone to error that it often jeopardizes our well-

Consider transience, for example. It would be great to remember all the details of every incident in your life, no matter how much time had passed. Or would it? Do you remember Jill Price, the woman we described at the beginning of this chapter, who has this ability and said it drives her crazy (see Jill's Story)?

It is helpful and sometimes important to forget information that is not current, like an old phone number. If we did not gradually forget information over time, our minds would be cluttered with details that we no longer need (Bjork, 2011; Bjork & Bjork, 1988). Information that is used infrequently is less likely to be needed in the future than information that is used more frequently over the same period (Anderson & Schooler, 1991, 2000). Memory, in essence, makes a bet that when we have not used information recently, we probably will not need it in the future. We win this bet more often than we lose it, making transience an adaptive property of memory. But we are acutely aware of the losses—

How are we better off with imperfect memories?

Similarly, absentmindedness and blocking can be frustrating, but they are side effects of our memory’s usually successful attempt to sort through incoming information, preserving details that are worthy of attention and recall, and discarding those that are less worthy.

Memory misattribution and suggestibility both occur because we often fail to recall the details of exactly when and where we saw a face or learned a fact. This is because memory is adapted to retain information that is most likely to be needed in the environment in which it operates. We seldom need to remember all the precise contextual details of every experience. Our memories carefully record such details only when we think they may be needed later, and most of the time we are better off for it. Furthermore, we often use memories to anticipate possible future events. As discussed earlier, memory is flexible, allowing us to recombine elements of past experience in new ways, so that we can mentally try out different versions of what might happen. But this very flexibility—

Although each of the seven sins can cause trouble in our lives, they have an adaptive side as well. You can think of the seven sins as costs we pay for benefits that allow memory to work as well as it does most of the time.

Memory’s mistakes can be classified into seven sins.

Transience is reflected by a rapid decline in memory followed by more gradual forgetting. With the passing of time, memory switches from detailed to general. Both decay and interference contribute to transience.

Absentmindedness results from failures of attention, shallow encoding, and the influence of automatic behaviours, and is often associated with forgetting to do things in the future.

Blocking occurs when stored information is temporarily inaccessible, as when information is on the tip of the tongue.

Memory misattribution happens when we experience a sense of familiarity but do not recall, or mistakenly recall, the specifics of when and where an experience occurred. Misattribution can result in eyewitness misidentification or false recognition. Individuals suffering from frontal lobe damage are especially susceptible to false recognition.

Suggestibility gives rise to implanted memories of small details or entire episodes. Suggestive techniques such as hypnosis or visualization can promote vivid recall of suggested events, and therapists’ use of suggestive techniques may be responsible for some individuals’ false memories of childhood traumas.

Bias reflects the influence of current knowledge, beliefs, and feelings on memory or past experiences. Bias can lead us to make the past consistent with the present, exaggerate changes between past and present, or remember the past in a way that makes us look good.

Persistence reflects the fact that emotional arousal generally leads to enhanced memory, whether we want to remember an experience or not. Persistence is partly attributable to the operation of hormonal systems influenced by the amygdala.

Although each of the seven sins can cause trouble in our lives, they have an adaptive side as well. You can think of the seven sins as costs we pay for benefits that allow memory to work as well as it does most of the time.

OTHER VOICES: Early Memories

In this eloquent passage from his recent book about memory, Pieces of Light, psychologist Charles Fernyhough (2012, pp. 1–

“Can you remember?”

It starts with a question from my 7-

”Can you remember the first fish you ever caught?”

I stand straight and look out at the farmland that slopes away from our hillside vantage point. I have not been fishing in thirty-

“I don’t know,” I reply. “I think so.”

What accounts for my uncertainty?

Try to recall your own earliest memory of a specific event from your life: How do you know when your recollection took place? How do you know that what you are remembering is the actual event? What kind of evidence would you require to be convinced that your memory is valid? Can you think of an experiment that might be conducted to provide that evidence?

One way to address this problem is to ask people about memories for events that have clearly definable dates, such as the birth of a younger sibling, the death of a loved one, or a family move. For example, one study found that individuals can recall events surrounding the birth of a sibling that occurred when they were about 2.4 years old (Eacott & Crawley, 1998).

Do you think that firm conclusions can be drawn from these kinds of studies? Can it be that memories of these early events are based on family conversations that took place long after the events occurred? An adult or a child who remembers having ice cream in the hospital as a 3-

Charles Fernyhough, Pieces of Light: How the New Science of Memory Illuminates the Stories We Tell About Our Pasts. London: Profile Books Ltd., 2012 / New York: Harper, 2013. Copyright © Charles Fernyhough, 2012. Reprinted by permission of the author, Profile Books Ltd., and HarperCollins Publishers.