8.3 Motivation: Getting Moved

Leonardo is a robot, so he does what he is programmed to do, but nothing more. Because he does not have wants and urges—

8.3.1 The Function of Emotion

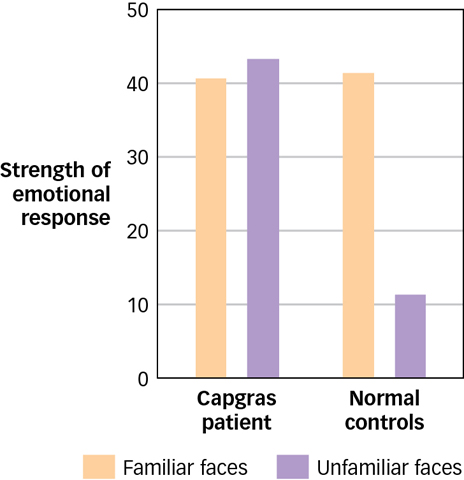

In the old science fiction film Invasion of the Body Snatchers, a young couple suspects that most of the people they know have been kidnapped by aliens and replaced with replicas. This sort of bizarre belief is a common story device in bad movies, but it is also the primary symptom of Capgras syndrome (see FIGURE 8.12). People who suffer from this syndrome typically believe that one or more of their family members are imposters. As one Capgras sufferer told her doctor, “He looks exactly like my father, but he really is not. He’s a nice guy, but he is not my father. … Maybe my father employed him to take care of me, paid him some money so he could pay my bills” (Hirstein & Ramachandran, 1997, p. 438).

Figure 8.12: Capgras Syndrome This graph shows the emotional responses (as measured by skin conductance) of a patient with Capgras syndrome and a group of control participants to a set of familiar and unfamiliar faces. Although the controls have stronger emotional responses to the familiar than to the unfamiliar faces, the Capgras patient has similar emotional responses to both (Hirstein & Ramachandran, 1997).

Figure 8.12: Capgras Syndrome This graph shows the emotional responses (as measured by skin conductance) of a patient with Capgras syndrome and a group of control participants to a set of familiar and unfamiliar faces. Although the controls have stronger emotional responses to the familiar than to the unfamiliar faces, the Capgras patient has similar emotional responses to both (Hirstein & Ramachandran, 1997).

This woman’s dad had not been body-

People with Capgras syndrome use their emotional experience as information about the world and, as it turns out, so do the rest of us. For example, people report having better lives when they are asked about their lives on a sunny day rather than a rainy day. Why? Because people naturally feel happier on sunny days, and they use their happiness as information about the quality of their lives (Schwarz & Clore, 1983). People who are in good moods believe that they have a higher probability of winning a lottery than do people who are in bad moods. Why? Because people use their moods as information about the likelihood of succeeding at a task (Isen & Patrick, 1983). We all know that satisfying lives and bright futures make us feel good—

How might emotions help us make decisions?

The information we get from our emotions is so useful that we can actually be lost without it. When neurologist Antonio Damasio was asked to examine a patient with an unusual form of brain damage, he asked the patient to choose between two dates for an appointment. It sounds like a simple decision, but for the next half hour, the patient enumerated reasons for and against each of the two possible dates, completely unable to decide in favour of one option or the other (Damasio, 1994). The problem was not any impairment of the patient’s ability to think or reason. On the contrary, he could think and reason all too well. What he could not do was feel. The patient’s injury had left him unable to experience emotion, so when he entertained one option (“If I come next Tuesday, I will have to cancel my lunch with Fred”), he did not feel any better or any worse than when he entertained another (“If I come next Wednesday, I will have to get up early to catch the bus”). And because he felt nothing when he thought about his options, he could not decide which one was best. Studies show that when individuals with this particular form of brain damage are given the opportunity to gamble, they make a lot of reckless bets because they do not feel the twinge of anxiety that tells them they are about to do something stupid. On the other hand, under certain conditions, such individuals make excellent investors, precisely because they are willing to take risks that most of us would not (Shiv et al., 2005).

If the first function of emotion is to provide us with information about the world, then the second function is to tell us what to do with that information. The hedonic principle is the claim that people are motivated to experience pleasure and avoid pain, and this claim has a long history. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle (350 BCE/1998) argued that the hedonic principle explained everything there was to know about human motivation: “It is for the sake of this that we all do all that we do.” We want many things, from peace and prosperity to health and security, but we want them for just one reason, and that is that they make us feel good. “Are these things good for any other reason except that they end in pleasure, and get rid of and avert pain?” asked Plato (380 BCE/1956). “Are you looking to any other standard but pleasure and pain when you call them good?” Plato and Aristotle were suggesting that pleasure is not just good: It is what good means.

According to the hedonic principle, then, our emotional experience can be thought of as a gauge that ranges from bad to good, and our primary motivation—

8.3.2 Instincts and Drives

If our primary motivation is to keep the needle on good, then which things push the needle in that direction and which things push it away? And where do these things get the power to push our needle around, and exactly how do they do the pushing? The answers to such questions lie in two concepts that have played an unusually important role in the history of psychology: instincts and drives.

8.3.2.1 Instincts

When a newborn baby is given a drop of sugar water, it smiles, and when it is given a cheque for $10 000, it acts like it could not care less. By the time the baby goes to university, these responses pretty much reverse. It seems clear that nature endows us with certain motivations and that experience endows us with others. William James (1890) called the natural tendency to seek a particular goal an instinct, which he defined as “the faculty of acting in such a way as to produce certain ends, without foresight of the ends, and without previous education in the performance” (p. 383). According to James, nature hardwired penguins, parrots, puppies, and people to want certain things without training and to execute the behaviours that produce these things without thinking. He and other psychologists of his time tried to make a list of what those things were.

Does an instinct explain behaviour, or just name it?

Unfortunately, they were quite successful, and in just a few decades their list of instincts had grown preposterously long and included some rather exotic entries, such as “the instinct to be secretive” and “the instinct to grind one’s teeth.” By 1924, sociologist Luther Bernard counted 5759 instincts and concluded that after three decades of list making, the term seemed to be suffering from “a great variety of usage and the almost universal lack of critical standards” (Bernard, 1924, p. 21). Furthermore, some psychologists began to worry that attributing the tendency for people to befriend each other to an “affiliation instinct” was more of a description than an explanation (Ayres, 1921; Dunlap, 1919; Field, 1921).

By 1930, the concept of instinct had fallen out of fashion. Not only did it fail to explain anything, but it also flew in the face of Western psychology’s hot new trend: behaviourism. Behaviourists rejected the concept of instinct on two grounds. First, they believed that behaviour should be explained by the external stimuli that evoke it and not by the hypothetical internal states on which it presumably depends. John Watson (1913) had written that “the time seems to have come when psychology must discard all reference to consciousness” (p. 163), and behaviourists saw instincts as just the sort of unnecessary “mind blather” that Watson forbade. Second, behaviourists wanted nothing to do with the notion of inherited behaviour because they believed that all complex behaviour was learned. Because instincts were inherited tendencies that resided inside the organism, behaviourists considered them doubly repugnant.

8.3.2.2 Drives

But within a few decades, some of Watson’s younger followers began to realize that the strict prohibition against the mention of internal states made certain phenomena difficult to explain. For example, if all behaviour is a response to an external stimulus, then why does a rat that is sitting still in its cage at 9:00 a.m. start wandering around and looking for food by noon? Nothing in the cage has changed, so why has the rat’s behaviour changed? What visible, measurable, external stimulus is the wandering rat responding to? The obvious answer is that the rat is responding to something inside itself, which meant that Watson’s young followers (the “new behaviourists” as they called themselves) were forced to look inside the rat to explain its wandering. How could they do that without talking about the “thoughts” and “feelings” that Watson had forbidden them to mention?

In what ways is the human body like a thermostat?

They began by noting that bodies are a bit like thermostats. When thermostats detect that the room is too cold, they send signals that initiate corrective actions such as turning on a furnace. Similarly, when bodies detect that they are underfed, they send signals that initiate corrective actions such as eating. Homeostasis is the tendency for a system to take action to keep itself in a particular state, and two of the new behaviourists, Clark Hull and Kenneth Spence, suggested that rats, people, and thermostats are all homeostatic mechanisms. To survive, an organism needs to maintain precise levels of nutrition, warmth, and so on, and when these levels depart from an optimal point, the organism receives a signal to take corrective action. That signal is called a drive, which is an internal state caused by physiological needs. According to Hull and Spence, it is not food per se that organisms find rewarding; it is the reduction of the drive for food. Hunger is a drive, a drive is an internal state, and when organisms eat, they are attempting to change their internal state.

Although the words instinct and drive are no longer widely used in psychology, both concepts have something to teach us. The concept of instinct reminds us that nature endows organisms with a tendency to seek certain things, and the concept of drive reminds us that this seeking is initiated by an internal state. The psychologist William McDougall (1930) called the study of motivation hormic psychology, which is a term derived from the Greek word for “urge,” and people clearly do have urges—

8.3.3 What the Body Needs

Why do some motivations take precedence over others?

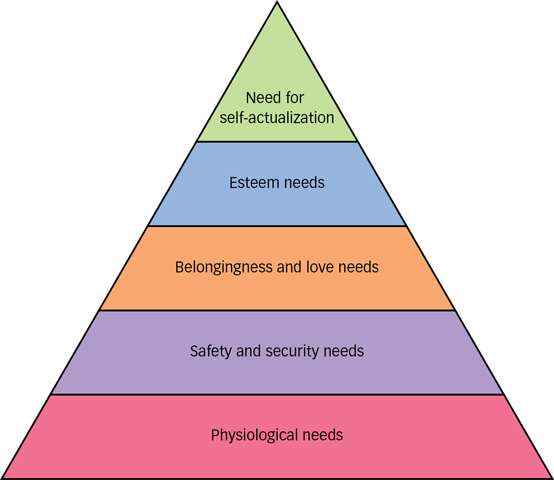

Abraham Maslow (1954) attempted to organize the list of human urges (or, as he called them, needs) in a meaningful way (see FIGURE 8.13). He noted that some needs (such as the need to eat) must be satisfied before others (such as the need to have friends), and he built a hierarchy of needs that had the most immediate needs at the bottom and the most deferrable needs at the top. Maslow suggested that, as a rule, people are more likely to experience a need when the needs below it are met. So when people are hungry or thirsty or exhausted, they are less likely to seek intellectual fulfillment or moral clarity (see FIGURE 8.14). According to Maslow, the needs that take precedence are typically those we share with other animals. For example, because all animals must survive and reproduce, all animals need to eat and mate. Human beings have these needs as well, but as you are about to see, they are more powerful and more complicated than most of us imagine (Kenrick et al., 2010).

Figure 8.13: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Human beings are motivated to satisfy a variety of needs. Psychologist Abraham Maslow thought these needs formed a hierarchy, with physiological needs forming a base and self-

Figure 8.13: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Human beings are motivated to satisfy a variety of needs. Psychologist Abraham Maslow thought these needs formed a hierarchy, with physiological needs forming a base and self-8.3.3.1 Survival: The Motivation for Food

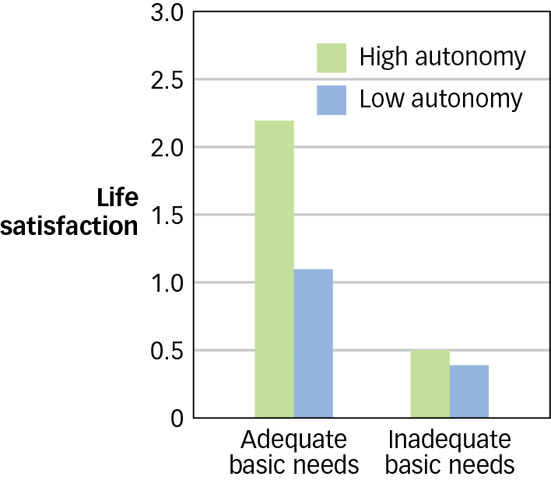

Figure 8.14: When Do Higher Needs Matter?Maslow was right. A recent study of 77 000 people in the world’s 51 poorest nations (Martin & Hill, 2012) showed that if people have their basic needs met, then autonomy (i.e., freedom to make their own decisions) increases their satisfaction with their lives. But when people do not have their basic needs met, autonomy makes little difference.

Figure 8.14: When Do Higher Needs Matter?Maslow was right. A recent study of 77 000 people in the world’s 51 poorest nations (Martin & Hill, 2012) showed that if people have their basic needs met, then autonomy (i.e., freedom to make their own decisions) increases their satisfaction with their lives. But when people do not have their basic needs met, autonomy makes little difference.

Animals convert matter into energy by eating, and they are driven to do this by an internal state called hunger. But what is hunger and where does it come from? At every moment, your body is sending signals to your brain about its current energy state. If your body needs energy, it sends a signal to tell your brain to switch hunger on, and if your body has sufficient energy, it sends a different signal to tell your brain to switch hunger off (Gropp et al., 2005). No one knows precisely what these signals are or how they are sent and received, but research has identified a variety of candidates.

What purpose does hunger serve?

For example, ghrelin is a hormone that is produced in the stomach and appears to be a signal that tells the brain to switch hunger on (Inui, 2001; Nakazato et al., 2001). When people are injected with ghrelin, they become intensely hungry and eat about 30 percent more than usual (Wren et al., 2001). Interestingly, ghrelin also binds to neurons in the hippocampus and temporarily improves learning and memory (Diano et al., 2006) so that we become just a little bit better at locating food when our bodies need it most. Leptin is a chemical secreted by fat cells, and it appears to be a signal that tells the brain to switch hunger off. It seems to do this by making food less rewarding (Farooqi et al., 2007). People who are born with a leptin deficiency have trouble controlling their appetites (Montague et al., 1997). For example, in 2002, medical researchers reported on the case of a 9-

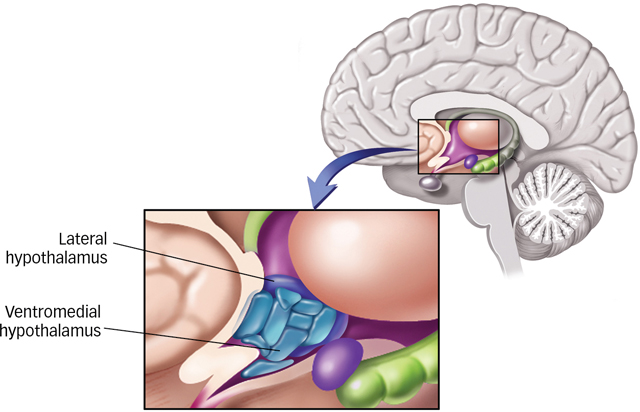

Whether hunger is one signal or many, the primary receiver of these signals is the hypothalamus. Different parts of the hypothalamus receive different signals (see FIGURE 8.15). The lateral hypothalamus receives orexigenic signals, and when it is destroyed, animals sitting in a cage full of food will starve themselves to death. The ventromedial hypothalamus receives anorexigenic signals, and when it is destroyed, animals will gorge themselves to the point of illness and obesity (Miller, 1960; Steinbaum & Miller, 1965). These two structures were once thought to be the “hunger centre” and “satiety centre” of the brain, but it turns out that this view is far too simple (Woods et al., 1998). Hypothalamic structures play an important role in turning hunger on and off, but the precise way in which they execute these functions is complex and poorly understood (Stellar & Stellar, 1985).

8.3.3.2 Eating Disorders

Figure 8.15: Hunger, Satiety, and the HypothalamusThe hypothalamus comprises many parts. In general, the lateral hypothalamus receives the signals that turn hunger on and the ventromedial hypothalamus receives the signals that turn hunger off.

Figure 8.15: Hunger, Satiety, and the HypothalamusThe hypothalamus comprises many parts. In general, the lateral hypothalamus receives the signals that turn hunger on and the ventromedial hypothalamus receives the signals that turn hunger off.

Feelings of hunger tell us when to eat and when to stop. But for the estimated 600 000 Canadians with eating disorders, eating is a much more complicated affair (Government of Canada, 2006). For instance, bulimia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by binge eating followed by purging. People with bulimia typically ingest large quantities of food in a relatively short period and then take laxatives or induce vomiting to purge the food from their bodies. These people are caught in a cycle: They eat to ease negative emotions such as sadness and anxiety, but then concern about weight gain leads them to experience negative emotions such as guilt and self-

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by an intense fear of being fat and severe restriction of food intake. People with anorexia tend to have a distorted body image that leads them to believe they are fat when they are actually emaciated, and they tend to be high-

What causes anorexia?

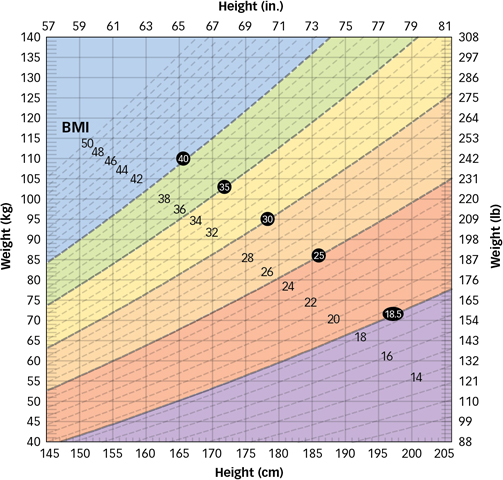

Anorexia may have both cultural and biological causes (Klump & Culbert, 2007). For example, women with anorexia typically believe that thinness equals beauty, and it is not hard to understand why. The average woman is 163 cm (5′4″) tall and weighs 69 kg (140 pounds), and so has a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 26.6. The typical fashion model is between 172 cm (5′ 8″) and 180 cm (5′11″), with a BMI of 16.2, which is considered underweight. Indeed, most university-

Bulimia and anorexia are problems for many people. But Canada’s most pervasive eating-

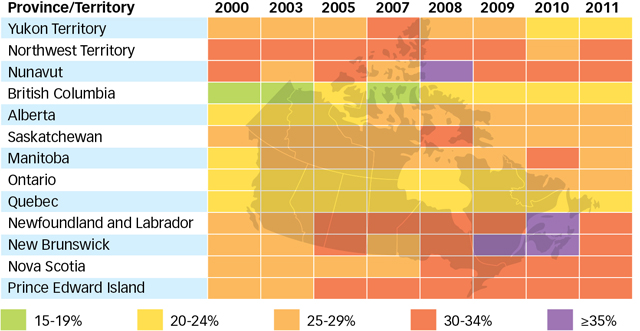

Figure 8.16: The Geography of ObesityThe chart shows the proportion of the adult population with a BMI in the obese range, and how this has changed over time. Obesity rates are increasing, and are particularly high in the Atlantic provinces and the North.

Figure 8.16: The Geography of ObesityThe chart shows the proportion of the adult population with a BMI in the obese range, and how this has changed over time. Obesity rates are increasing, and are particularly high in the Atlantic provinces and the North.

FIGURE 8.17 and TABLE 8.1 allow you to compute your BMI, and the odds are that you will not like what you learn. Although BMI is a better predictor of mortality for some people than for others (Romero-

Figure 8.17: Determining BMIFind your weight along the vertical axis. Draw a horizontal line from that value. Find your height on the horizontal axis. Draw a vertical line. The point of intersection of the two lines indicates your BMI. Use Table 8.1 to determine your level of health.

Figure 8.17: Determining BMIFind your weight along the vertical axis. Draw a horizontal line from that value. Find your height on the horizontal axis. Draw a vertical line. The point of intersection of the two lines indicates your BMI. Use Table 8.1 to determine your level of health.

|

Classification |

BMI Category (kg/m2) |

Health Problems Risk |

|---|---|---|

|

Underweight |

< 18.5 |

increased |

|

Normal weight |

18.5– |

least |

|

Overweight |

25.0– |

increased |

|

Obese Class I |

30.0– |

high |

|

Obese Class II |

35.0– |

very high |

|

Obese Class III |

≥ 40.0 |

extremely high |

|

Source: Health Canada, 2003. Canadian Guidelines for Body Weight Classification in Adults. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada. |

||

Obesity has many causes. For example, obesity is highly heritable (Allison et al., 1996) and may have a genetic component, which may explain why a disproportionate amount of the weight gained by Canadians in the past few decades has been gained by those who were already the heaviest (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2011a). Some studies suggest that “obesogenic” toxins in the environment can disrupt the functioning of the endocrine system and predispose people to obesity (Grün & Blumberg, 2006; Newbold et al., 2005), whereas other studies suggest that obesity can be caused by a dearth of “good bacteria” in the gut (Liou et al., 2013). Whatever the cause, obese people are often leptin-

Why do people overeat?

Genes, pollutants, and bacteria have all been implicated in the tendency toward obesity. But in most cases the cause of obesity is not such a mystery: We simply eat too much. We eat when we are hungry, of course, but we also eat when we are sad or anxious, or when we are presented with a visually appealing or delicious food, or when everyone else is eating (Herman, Roth, & Polivy, 2003). Sometimes we eat simply because the clock tells us to, which is why people with amnesia will happily eat a second lunch shortly after finishing an unremembered first one (Rozin et al., 1998) (see The Real World: Jeet Jet?). Although all of these factors influence eating in both normal-

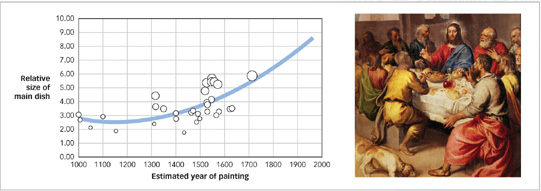

Blame the design. Hundreds of thousands of years ago, the main food-

THE REAL WORLD: Jeet Jet?*

In 1923, a reporter for the New York Times asked the British mountaineer George Leigh Mallory why he wanted to climb Mount Everest. Mallory replied: “Because it is there.”

Apparently, that is also the reason why we eat. Brian Wansink and colleagues (2005) wondered whether the amount of food people eat is influenced by the amount of food they see in front of them. So they invited participants to their laboratory, sat them down in front of a large bowl of tomato soup, and told them to eat as much as they wanted. In one condition of the study, a server came to the table and refilled the participant’s bowl whenever it got down to about a quarter full. In another condition, the bowl was not refilled by a server. Rather, unbeknownst to the participants, the bottom of the bowl was connected by a long tube to a large vat of soup, so whenever the participant ate from the bowl it would slowly and almost imperceptibly refill itself.

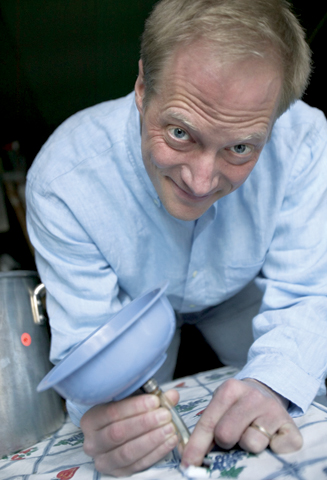

Researcher Brian Wansink and his bottomless bowl of soup.

Researcher Brian Wansink and his bottomless bowl of soup.What the researchers found was sobering. Participants who unknowingly ate from a “bottomless bowl” consumed a whopping 73 percent more soup than those who ate from normal bowls—

It seems that we find it easier to keep track of what we are eating than how much, and this can cause us to overeat even when we are trying our best to do just the opposite. For instance, one study showed that diners at an Italian restaurant often chose to eat butter on their bread rather than dipping it in olive oil because they thought that doing so would reduce the number of calories per slice. And they were right. What they did not realize, however, is that they would unconsciously compensate for this reduction in calories by eating 23 percent more bread during the meal (Wansink & Linder, 2003).

This and other research suggests that one of the best ways to reduce our waists is simply to count our bites.

*“Jeet jet?” is a phrase by Pittsburghers that means “Did you eat yet?”

It is all too easy to overeat and become overweight or obese, and it is all too difficult to reverse course. The human body resists weight loss in two ways. First, when we gain weight, we experience an increase in both the size and the number of fat cells in our bodies (usually in our abdomens if we are male and in our thighs and buttocks if we are female). But when we lose weight, we experience a decrease in the size of our fat cells but no decrease in their number. Once our bodies have added a fat cell, that cell is pretty much there to stay. It may become thinner when we diet, but it is unlikely to die.

Why is dieting so difficult and ineffective?

Second, our bodies respond to dieting by decreasing our metabolism, which is the rate at which energy is used by the body. When our bodies sense that we are living through a famine (which is what they conclude when we refuse to feed them), they find more efficient ways to turn food into fat: a great trick for our ancestors but a real nuisance for us. Indeed, when rats are overfed, then put on diets, then overfed again and put on diets again, they gain weight faster and lose it more slowly the second time around, which suggests that with each round of dieting, their bodies become increasingly efficient at converting food to fat (Brownell et al., 1986). The bottom line is that avoiding obesity is easier than overcoming it (Casazza et al., 2013).

And avoiding it is not as difficult as you might think. For instance, just by placing hard-

8.3.3.3 Reproduction: The Motivation for Sex

Food motivates us because it is essential to our survival. But sex is also essential to our survival (at least to the survival of our DNA), which is why evolution has ensured that a desire for sex is wired deep into the brain of almost every one of us. In some ways, that wiring scheme is simple: Glands secrete hormones that travel through the blood to the brain and stimulate sexual desire. But which hormones, which parts of the brain, and what triggers the launch in the first place?

The hormone dihydroepiandosterone (DHEA) seems to be involved in the initial onset of sexual desire. Both boys and girls begin producing this slow-

The answer appears to be yes—

The story for human beings is far more interesting. The females of most mammalian species (e.g., dogs, cats, and rats) have little or no interest in sex except when their estrogen levels are high, which happens when they are ovulating (i.e., when they are “in estrus” or “in heat”). In other words, estrogen regulates both ovulation and sexual interest in these mammals. But female human beings can be interested in sex at any point in their monthly cycles. Although the level of estrogen in a woman’s body changes dramatically over the course of her monthly menstrual cycle, studies suggest that sexual desire changes little, if at all. Somewhere in the course of our evolution, it seems, women’s sexual interest became independent of their ovulation.

Why do female humans not show clear signs of ovulation?

Some theorists have speculated that the advantage of this independence was that it made it more difficult for males to know whether a female was in the fertile phase of her monthly cycle. Male mammals often guard their mates jealously when their mates are ovulating, but go off in search of other females when their mates are not. If a male cannot use his mate’s sexual receptivity to tell when she is ovulating, then he has no choice but to stay around and guard her all the time. For females who are trying to keep their mates at home so that they will contribute to the rearing of children, sexual interest that is continuous and independent of fertility may be an excellent strategy.

If estrogen is not the hormonal basis of women’s sex drives, then what is? Two pieces of evidence suggest that the answer is testosterone—

8.3.3.4 Sexual Activity

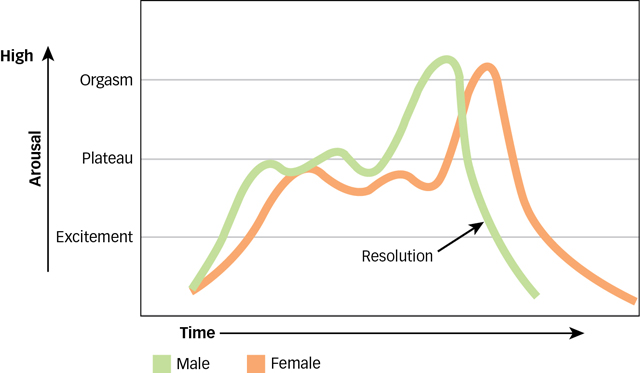

Men and women may have different levels of sexual drive, but their physiological responses during sex are fairly similar. Prior to the 1960s, data on human sexual behaviour consisted primarily of people’s answers to questions about their sex lives (and you may have noticed that this is a topic about which people do not always tell the truth). William Masters and Virginia Johnson changed all that by conducting groundbreaking studies in which they actually measured the physical responses of hundreds of volunteers as they masturbated or had sex in the laboratory (Masters & Johnson, 1966). Their work led to a deeper understanding of the human sexual response cycle, which refers to the stages of physiological arousal during sexual activity (see FIGURE 8.18). Human sexual response has four phases:

Figure 8.18: The Human Sexual Response CycleThe pattern of the sexual response cycle is quite similar for men and for women. Both men and women go through the excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution phases, though the timing of their response may differ.

Figure 8.18: The Human Sexual Response CycleThe pattern of the sexual response cycle is quite similar for men and for women. Both men and women go through the excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution phases, though the timing of their response may differ.

During the excitement phase, muscle tension and blood flow increase in and around the sexual organs, heart and respiration rates increase, and blood pressure rises. Both men and women may experience erect nipples and a “sex flush” on the skin of the upper body and face. A man’s penis typically becomes erect or partially erect and his testicles draw upward, while a woman’s vagina typically becomes lubricated and her clitoris becomes swollen.

During the plateau phase, heart rate and muscle tension increase further. A man’s urinary bladder closes to prevent urine from mixing with semen, and muscles at the base of his penis begin a steady rhythmic contraction. A man’s Cowper gland may secrete a small amount of lubricating fluid (which, by the way, often contains enough sperm to cause pregnancy). A woman’s clitoris may withdraw slightly, and her vagina may become more lubricated. Her outer vagina may swell, and her muscles may tighten and reduce the diameter of the opening of the vagina.

During the orgasm phase, breathing becomes extremely rapid and the pelvic muscles begin a series of rhythmic contractions. Both men and women experience quick cycles of muscle contraction of the anus and lower pelvic muscles, and women often experience uterine and vaginal contractions as well. During this phase, men ejaculate about two to five millilitres of semen (depending on how long it has been since their last orgasm and how long they were aroused prior to ejaculation). Ninety-

five percent of heterosexual men and 69 percent of heterosexual women reported having an orgasm during their last sexual encounter (Richters et al., 2006); although roughly 15 percent of women never experience orgasm, less than half experience orgasm from intercourse alone, and roughly half report having “faked” an orgasm at least once (Wiederman, 1997). The frequency with which women have orgasms seems to have a genetic component (Dawood et al., 2005). And it goes without saying that when men and women have orgasms, they typically experience them as intensely pleasurable. During the resolution phase, muscles relax, blood pressure drops, and the body returns to its resting state. Most men and women experience a refractory period, during which further stimulation does not produce excitement. This period may last from minutes to days and is typically longer for men than for women.

Why do people have sex?

Although sex is typically a prerequisite for reproduction, the vast majority of sexual acts are not meant to produce babies. University students, for example, are rarely aiming to get pregnant, but they do have sex because of physical attraction (“The person had beautiful eyes”), as a means to an end (“I wanted to be popular”), to increase emotional connection (“I wanted to communicate at a deeper level”), and to alleviate insecurity (“It was the only way my partner would spend time with me”) (Meston & Buss, 2007). Although men are more likely than women to report having sex for purely physical reasons, TABLE 8.2 shows that men and women do not differ dramatically in their most frequent responses about why they have sex. It is worth noting that not all sex is motivated by reasons like these: About half of university-

|

Top Ten Reasons Why Women and Men Report Having Sex |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Women |

Men |

|

|

1 |

I was attracted to the person. |

I was attracted to the person. |

|

2 |

I wanted to experience the physical pleasure. |

It feels good. |

|

3 |

It feels good. |

I wanted to experience the physical pleasure. |

|

4 |

I wanted to show my affection to the person. |

It is fun. |

|

5 |

I wanted to express my love for the person. |

I wanted to show my affection to the person. |

|

6 |

I was sexually aroused and wanted the release. |

I was sexually aroused and wanted the release. |

|

7 |

I was “horny.” |

I was “horny.” |

|

8 |

It is fun. |

I wanted to express my love for the person. |

|

9 |

I realized I was in love. |

I wanted to achieve an orgasm. |

|

10 |

I was “in the heat of the moment.” |

I wanted to please my partner. |

|

Source: Meston & Buss, 2007. |

||

8.3.4 What the Mind Wants

Survival and reproduction are every animal’s first order of business, so it is no surprise that we are strongly motivated by food and sex. But we are motivated by other things too. We crave kisses of both the chocolate and romantic variety, but we also crave friendship and respect, security and certainty, wisdom and meaning, and a whole lot more. Our psychological motivations can be every bit as powerful as our biological motivations, but they differ in two ways.

First, although we share our biological motivations with most other animals, our psychological motivations are relatively unique. Chimps and rabbits and robins and turtles are all motivated to have sex, but only human beings seem motivated to imbue the act with meaning. Second, although our biological motivations are few—

8.3.4.1 Intrinsic versus Extrinsic

Taking a psychology exam and eating a french fry are different in many ways. One makes you tired and the other makes you chubby, one requires that you move your lips and the other requires that you do not, and so on. But the key difference between these activities is that one is a means to an end and one is an end in itself. An intrinsic motivation is a motivation to take actions that are themselves rewarding. When we eat a french fry because it tastes good, exercise because it feels good, or listen to music because it sounds good, we are intrinsically motivated. These activities do not have a payoff: They are a payoff. Conversely, an extrinsic motivation is a motivation to take actions that lead to reward. When we floss our teeth so we can avoid gum disease (and get dates), when we work hard for money so we can pay our rent (and get dates), and when we take an exam so we can get a university degree (and get money to get dates), we are extrinsically motivated. None of these things directly bring pleasure, but all may lead to pleasure in the long run.

Why should people delay gratification?

Extrinsic motivation gets a bad rap. Canadians tend to believe that people should “follow their hearts” and “do what they love,” and we feel sorry for students who choose courses just to please their parents and for parents who choose jobs just to earn a pile of money. But the fact is that our ability to engage in behaviours that are unrewarding in the present because we believe they will bring greater rewards in the future is one of our species’ most significant talents, and no other species can do it quite as well as we can (Gilbert, 2006). In research on the ability to delay gratification (Ayduk et al., 2007; Mischel et al., 2004), people are typically faced with a choice between getting something they want right now (e.g., a scoop of ice cream) or waiting and getting more of what they want later (e.g., two scoops of ice cream). Waiting for ice cream is a lot like taking an exam or flossing: It is not much fun, but you do it because you know you will reap greater rewards in the end. Studies show that 4-

Why do rewards sometimes backfire?

There is a lot to be said for intrinsic motivation too (Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008). People work harder when they are intrinsically motivated, they enjoy what they do more, and they do it more creatively. Both kinds of motivation have advantages, which is why many of us try to build lives in which we are both intrinsically and extrinsically motivated by the same activity—

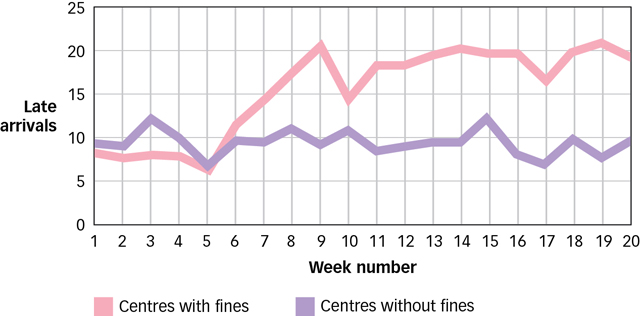

Just as rewards can undermine intrinsic motivation, punishments can create it. In one study, children who had no intrinsic interest in playing with a toy suddenly gained an interest when the experimenter threatened to punish them if they touched it (Aronson, 1963). University students who had no intrinsic motivation to cheat on a test were more likely to do so if the experimenter explicitly warned against it (Wilson & Lassiter, 1982). Threats can suggest that a forbidden activity is desirable, and they can also have the paradoxical consequence of promoting the very behaviours they are meant to discourage. For example, when a group of daycare centres got fed up with parents who arrived late to pick up their children, some of them instituted a financial penalty for tardiness. As FIGURE 8.19 shows, the financial penalty caused an increase in late arrivals (Gneezy & Rustichini, 2000). Why? Because parents are intrinsically motivated to fetch their kids and they generally do their best to be on time. But when the daycare centres imposed a fine for late arrival, the parents became extrinsically motivated to fetch their children—

Figure 8.19: When Threats BackfireThreats can cause behaviours that were once intrinsically motivated to become extrinsically motivated. Daycare centres that instituted fines for late-

Figure 8.19: When Threats BackfireThreats can cause behaviours that were once intrinsically motivated to become extrinsically motivated. Daycare centres that instituted fines for late-8.3.4.2 Conscious versus Unconscious

When prizewinning artists or scientists are asked to explain their achievements, they typically say things like, “I wanted to liberate colour from form” or “I wanted to cure diabetes.” They almost never say, “I wanted to exceed my father’s accomplishments, thereby proving to my mother that I was worthy of her love.” People clearly have conscious motivations, which are motivations of which people are aware, but they also have unconscious motivations, which are motivations of which people are not aware (Aarts, Custers, & Marien, 2008; Bargh et al., 2001; Hassin, Bargh, & Zimerman, 2009).

For example, psychologists David McClelland and John Atkinson argued that people vary in their need for achievement, which is the motivation to solve worthwhile problems (McClelland et al., 1953). They argued that this basic motivation is unconscious and thus must be measured with special techniques such as the Thematic Apperception Test, which presents people with a series of drawings and asks them to tell stories about them. The amount of “achievement-

What makes people conscious of their motivations?

What determines whether we are conscious of our motivations? Most actions have more than one motivation, and Robin Vallacher and Daniel Wegner (1985, 1987) have suggested that the ease or difficulty of performing the action determines which of these motivations we will be aware of. When actions are easy (e.g., screwing in a light bulb), we are aware of our most general motivations (e.g., to be helpful), but when actions are difficult (e.g., wrestling with a light bulb that is stuck in its socket), we are aware of our more specific motivations (e.g., to get the threads aligned). Vallacher and Wegner argued that people are usually aware of the general motivations for their behaviour and only become aware of their more specific motivations when they encounter problems. For example, participants in an experiment drank coffee either from a normal mug or from a mug that had a heavy weight attached to the bottom, which made the mug difficult to manipulate. When asked what they were doing, those who were drinking from the normal mug explained that they were “satisfying needs,” whereas those who were drinking from the weighted mug explained that they were “swallowing” (Wegner et al., 1984). The ease with which we can execute an action is one of many factors that determine whether we are or are not conscious of our motivations.

8.3.4.3 Approach versus Avoidance

The poet James Thurber (1956) wrote: “All men should strive to learn before they die/What they are running from, and to, and why.” The hedonic principle describes two conceptually distinct motivations: a motivation to “run to” pleasure and a motivation to “run from” pain. The first it what psychologists call an approach motivation, which is a motivation to experience a positive outcome. The second is an avoidance motivation which is a motivation not to experience a negative outcome. Pleasure is not just the lack of pain, and pain is not just the lack of pleasure. They are independent experiences that occur in different parts of the brain (Davidson et al., 1990; Gray, 1990).

Research suggests that, all else being equal, avoidance motivations tend to be more powerful than approach motivations. Most people will turn down a chance to bet on a coin flip that would pay them $10 if it came up heads but would require them to pay $8 if it came up tails, because they believe that the pain of losing $8 will be more intense than the pleasure of winning $10 (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). Because people expect losses to have more powerful emotional consequences than equal-

What is the difference between being motivated to avoid and being motivated to approach?

On average, avoidance motivation is stronger than approach motivation, but the relative strength of these two tendencies does differ somewhat from person to person. TABLE 8.3 shows a series of questions that have been used to measure the relative strength of a person’s approach and avoidance tendencies (Carver & White, 1994). Research shows that people who are described by the high-

|

To what extent do each of these items describe you? The items in red measure the strength of your avoidance tendency and the items in green measure the strength of your approach tendency. |

|---|

| • Even if something bad is about to happen to me, I rarely experience fear or nervousness. (LOW AVOIDANCE) |

| • I go out of my way to get things I want. (HIGH APPROACH) |

| • When I am doing well at something, I love to keep at it. (HIGH APPROACH) |

| • I am always willing to try something new if I think it will be fun. (HIGH APPROACH) |

| • When I get something I want, I feel excited and energized. (HIGH APPROACH) |

| • Criticism or scolding hurts me quite a bit. (HIGH AVOIDANCE) |

| • When I want something, I usually go all- |

| • I will often do things for no other reason than that they might be fun. (HIGH APPROACH) |

| • If I see a chance to get something I want, I move on it right away. (HIGH APPROACH) |

| • I feel pretty worried or upset when I think or know somebody is angry at me. (HIGH AVOIDANCE) |

| • When I see an opportunity for something I like, I get excited right away. (HIGH APPROACH) |

| • I often act on the spur of the moment. (HIGH APPROACH) |

| • If I think something unpleasant is going to happen, I usually get pretty “worked up.” (HIGH AVOIDANCE) |

| • When good things happen to me, it affects me strongly. (HIGH APPROACH) |

| • I feel worried when I think I have done poorly at something important. (HIGH AVOIDANCE) |

| • I crave excitement and new sensations. (HIGH APPROACH) |

| • When I go after something, I use a “no holds barred” approach. (HIGH APPROACH) |

| • I have very few fears compared to my friends. (LOW AVOIDANCE) |

| • It would excite me to win a contest. (HIGH APPROACH) |

| • I worry about making mistakes. (HIGH AVOIDANCE) |

|

Source: Carver & White, 1994. |

And what is probably the biggest thing that people want to avoid? All animals strive to stay alive, but only human beings realize that this striving is ultimately in vain and that death is life’s inevitable end. Some psychologists have suggested that the motivation to avoid the anxiety associated with death creates a sense of “existential terror” and that much of our behaviour is merely an attempt to manage it. Terror management theory is a theory about how people respond to knowledge of their own mortality, and it suggests that—

How do people deal with knowledge of death?

Terror management theory gives rise to the mortality-

Emotions motivate us indirectly by providing information about the world, but they also motivate us directly.

The hedonic principle suggests that people approach pleasure and avoid pain, and that this basic motivation underlies all others. All organisms are born with some motivations and acquire others through experience.

When the body experiences a deficit, we experience a drive to remedy it. Biological motivations generally take precedence over psychological motivations. An example of a biological motivation is hunger, which is the result of a complex system of physiological processes, and problems with this system can lead to eating disorders and obesity, both of which are difficult to overcome. Another example of a biological motivation is sexual interest. Men and women experience roughly the same sequence of physiological events during sex, they engage in sex for most of the same reasons, and both have sex drives that are regulated by testosterone.

People have many psychological motivations that vary on three key dimensions. Intrinsic motivations can be undermined by extrinsic rewards and punishments. People tend to be conscious of their more general motivations unless difficulty with the production of action forces them to become conscious of more specific motivations that are typically unconscious. Avoidance motivations are generally more powerful than approach motivations, although this is truer for some people than for others.