9.7 Transforming Information: How We Reach Conclusions

Reasoning is a mental activity that consists of organizing information or beliefs into a series of steps in order to reach conclusions. Not surprisingly, sometimes our reasoning seems sensible and straightforward, and other times it seems a little off. Consider some reasons offered by people who filed actual insurance accident claims (www.swapmeetdave.com):

“I left for work this morning at 7:00 a.m. as usual when I collided straight into a bus. The bus was 5 minutes early.”

“Coming home, I drove into the wrong house and collided with a tree I don’t have.”

“My car was legally parked as it backed into another vehicle.”

“The indirect cause of the accident was a little guy in a small car with a big mouth.”

“Windshield broke. Cause unknown. Probably voodoo.”

When people like these hapless drivers argue with you in a way that seems inconsistent or poorly thought out, you may accuse them of being “illogical.” Logic is a system of rules that specifies which conclusions follow from a set of statements. To put it another way, if you know that a given set of statements is true, logic will tell you which other statements must also be true. If the statement “Jack and Jill went up the hill” is true, then according to the rules of logic, the statement “Jill went up the hill” must also be true. To accept the truth of the first statement while denying the truth of the second statement would be a contradiction. Logic is a tool for evaluating reasoning, but it should not be confused with the process of reasoning itself. Equating logic and reasoning would be like equating carpenter’s tools (logic) with building a house (reasoning).

9.7.1 Practical, Theoretical, and Syllogistic Reasoning

Earlier in the chapter, we discussed decision making, which often depends on reasoning with probabilities. Practical reasoning and theoretical reasoning also allow us to make decisions (Walton, 1990). Practical reasoning is figuring out what to do, or reasoning directed toward action. Means–

Suppose you asked your friend Bruce to take you to a concert, and he said that his car was not working. You would undoubtedly find another way to get to the concert. If you then spied him driving into the concert parking lot, you might reason: “Bruce told me his car was not working. He just drove into the parking lot. If his car was not working, he could not drive it here. So, either he suddenly fixed it, or he was lying to me. If he was lying to me, he’s not much of a friend.” Notice the absence of an action-

If you concluded from these examples that we are equally adept at both types of reasoning, experimental evidence suggests you are wrong. People generally find figuring out what to do easier than deciding which beliefs follow logically from other beliefs. In cross-

|

Experimenter: |

All Kpelle men are rice farmers. Mr. Smith (this is a Western name) is not a rice farmer. Is he a Kpelle man? |

|

Farmer: |

I do not know the man in person. I have not laid eyes on the man himself. |

|

Experimenter: |

Just think about the statement. |

|

Farmer: |

If I know him in person, I can answer that question, but since I do not know him in person, I cannot answer that question. |

|

Experimenter: |

Try and answer from your Kpelle sense. |

|

Farmer: |

If you know a person, if a question comes up about him, you are able to answer. But if you do not know a person, if a question comes up about him, it is hard for you to answer it. |

As this excerpt shows, the farmer does not seem to understand that the problem can be resolved with theoretical reasoning. Instead, he is concerned with retrieving and verifying facts, a strategy that does not work for this type of task.

A very different picture emerges when members of preliterate cultures are given tasks that require practical reasoning. One well-

A child has to give you what you ask for just in the same way as when he asks for anything you give it to him. Why then should he be selfish with what he has? A parent loves his child and maybe the son refused without knowing the need of helping his father. … By showing respect to one another, friendship between us is assured, and as a result this will increase the prosperity of our family.

What have cross-

This preliterate individual had little difficulty understanding this practical problem. His response is intelligent, insightful, and well reasoned. A principal finding from this kind of cross-

Educated individuals in industrial societies are prone to similar failures in reasoning, as illustrated by belief bias: People’s judgments about whether to accept conclusions depend more on how believable the conclusions are than on whether the arguments are logically valid (Evans, Barston, & Pollard, 1983) (see also The Real World box). For example, syllogistic reasoning assesses whether a conclusion follows from two statements that are assumed to be true. Consider the two following syllogisms, evaluate the argument, and ask yourself whether or not the conclusions must be true if the statements are true:

Syllogism 1

- Statement 1: No cigarettes are inexpensive.

- Statement 2: Some addictive things are inexpensive.

- Conclusion: Some addictive things are not cigarettes.

THE REAL WORLD: From Zippers to Political Extremism: An Illusion of Understanding

Zippers are extremely helpful objects and we have all used them more times than we could possibly recall. Most of us also think that we have a pretty good understanding of how a zipper works—

Recent research suggests that the illusion of explanatory depth applies to a very different domain of everyday life: political extremism. Many pressing issues of our times, such as climate change and national security, share two features: They involve complex policies and tend to generate extreme views at either end of the political spectrum. Fernbach and his colleagues (2013) asked whether polarized views occur because people think that they understand the relevant policies in greater depth than they actually do. To investigate this hypothesis, the researchers asked American participants to rate their positions regarding six contemporary American political policies (sanctions on Iran for its nuclear program, raising the retirement age for social security, single-

Fernbach and his colleagues (2013) found that after attempting to generate detailed explanations, participants provided lower ratings of understanding and less extreme positions concerning all six policies than they had previously. Furthermore, those participants who exhibited the largest decreases in their pre-

The overall pattern of results supports the idea that extreme political views are enabled, at least in part, by an illusion of explanatory depth: Once people realize that they do not understand the relevant policy issues in as much depth as they had thought, their views moderate. There probably are not too many psychological phenomena that are well-

Syllogism 2

- Statement 1: No addictive things are inexpensive.

- Statement 2: Some cigarettes are inexpensive.

- Conclusion: Some cigarettes are not addictive.

If you are like most people, you probably concluded that the reasoning is valid in Syllogism 1 but flawed in Syllogism 2. Indeed, researchers found that nearly 100 percent of participants accepted the first conclusion as valid, but fewer than half accepted the second (Evans, Barston, & Pollard, 1983). But notice that the syllogisms are in exactly the same form. This form of syllogism is valid, so both conclusions are valid. Evidently, the believability of the conclusions influences people’s judgments.

9.7.2 Reasoning and the Brain

Research using fMRI provides novel insights into belief biases on reasoning tasks. In belief-

Syllogism 3

- Statement 1: No codes are highly complex.

- Statement 2: Some quipu are highly complex.

- Conclusion: No quipu are codes.

Belief-

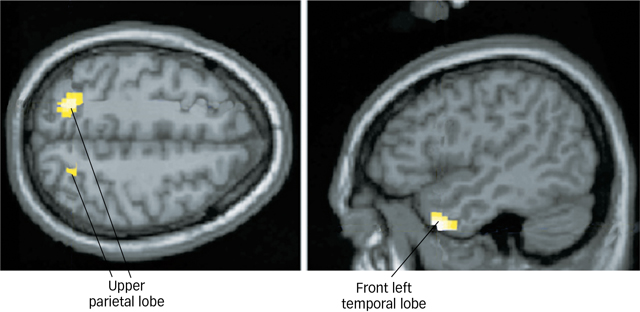

Figure 9.22: Active Brain Regions in Reasoning These images from an fMRI study show that different types of reasoning activate different brain regions. (a) Areas within the parietal lobe were especially active during logical reasoning that is not influenced by prior beliefs (belief-

Figure 9.22: Active Brain Regions in Reasoning These images from an fMRI study show that different types of reasoning activate different brain regions. (a) Areas within the parietal lobe were especially active during logical reasoning that is not influenced by prior beliefs (belief-The success of human reasoning depends on the content of the argument or scenario under consideration. People seem to excel at practical reasoning while stumbling when theoretical reasoning requires evaluation of the truth of a set of arguments.

Belief bias describes a distortion of judgments about conclusions of arguments, causing people to focus on the believability of the conclusions rather than on the logical connections between the premises.

Neuroimaging provides evidence that different brain regions are associated with different types of reasoning.

We can see here and elsewhere in the chapter that some of the same strategies that earlier helped us to understand perception, memory, and learning—

carefully examining errors and trying to integrate information about the brain into our psychological analyses— are equally helpful in understanding language and thought.