101.5 Preface

Why are you reading the preface? The book really gets going in about 10 pages, so why are you here instead of there? Are you the kind of person who cannot stand the idea of missing something? Are you trying to justify the cost of the book by consuming every word? Did you just open to this page out of habit? Are you starting to think that maybe you made a big mistake?

For as long as we can remember, we have been asking questions like these about ourselves, about our friends, and about anyone else who did not run away fast enough. Our curiosity about why people think, feel, and act as they do drew each of us into our first psychology course, and though we remember being swept away by the lectures, we do not remember much about our textbooks. That is probably because those textbooks were little more than colourful encyclopedias of facts, names, and dates. Little wonder that we sold them back to the bookstore the moment we finished our final exams.

When we became psychology professors, we did the things that psychology professors often do: We taught classes, we conducted research, and we wore sweater vests long after they stopped being fashionable. We also wrote stuff that people truly enjoyed reading, and that made us wonder why no one had ever written an introductory psychology textbook that students truly enjoyed reading. After all, psychology is the single most interesting subject in the known universe, so why should a psychology textbook not be the single most interesting object in a student’s backpack? We could not think of a reason, so we sat down and wrote the book that we wished we had been given as students. The first American edition of Psychology was published in 2008, and the reaction to it was nothing short of astounding. We had never written a textbook before, so we did not know exactly what to expect, but never in our wildest dreams did we imagine that we would win the Pulitzer Prize!

Which was good, because we did not. But what did happen was even better: We started getting letters and emails from students all over the country who just wanted to tell us how much they liked reading our book. They liked the content, of course, because as we may have already mentioned, psychology is the single most interesting subject in the known universe. But they also liked the fact that our textbook did not sound like a textbook. It was not written in the stodgy voice of the announcer from one of those nature films that we all saw in seventh grade biology (“Behold the sea otter, nature’s furry little scavenger”). Rather, it was written in our voices—

The last edition of our book was a hit—

Changes in the Third Edition

New focus on critical thinking

As sciences uncover new evidence and develop new theories, scientists change their minds. Some of the facts that students learn in a science course will still be facts a decade later, and others will require qualification or will turn out to have just been plain wrong. That’s why students not only need to learn the facts but also how to think about facts—

New section “Learning in the Classroom”

Like other psychology textbooks, the first two editions of our text provided in-

New research

A textbook should give students a complete tour of the classics, of course, but it should also take them out dancing on the cutting edge. We want students to realize that psychology is not a museum piece—

|

Chapter Number |

Hot Science |

|---|---|

|

1 |

Psychology as a Hub Science, p. 34 |

|

2 |

Do Violent Movies Make Peaceful Streets?, p. 64 |

|

3 |

Epigenetics and the Persisting Effects of Early Experiences, p. 112 |

|

4 |

Taste: From the Top Down, p. 170 |

|

5 |

Disorders of Consciousness, p. 185 |

|

6 |

Sleep on It, p. 233 |

|

7 |

Dopamine and Reward Learning in Parkinson’s Disease, p. 292 |

|

8 |

The Body of Evidence, p. 325 |

|

9 |

Sudden Insight and the Brain, p. 386 |

|

10 |

Dumb and Dumber?, p. 414 |

|

11 |

A Statistician in the Crib, p. 435 |

|

11 |

The End of History Illusion, p. 460 |

|

12 |

Personality on the Surface, p. 479 |

|

13 |

Mouse Over, p. 516 |

|

13 |

The Wedding Planner, p. 538 |

|

14 |

Can Discrimination Cause Stress and Illness?, p. 552 |

|

15 |

Optimal Outcome in Autism Spectrum Disorder, p. 615 |

|

16 |

“Rebooting” Psychological Treatment, p. 642 |

Fully updated coverage of DSM-5

One area where there has been lots of new research—

New organization

We have rearranged our table of contents to better fit our changing sense of how psychology is best taught. Specifically, we have moved the chapter on Stress and Health forward so that it now appears before the chapters on Psychological Disorders and Treatment of Psychological Disorders. We think this change improves the flow of the book in several ways. First, as you will learn, the experience of stress has a lot to do with interpersonal events and how we respond to them, information that you will have just learned about in the chapters on Personality and Social Psychology. Second, current models of psychological disorders view them as resulting from an interaction of some underlying predisposition (e.g., genetic or otherwise) and stressful life events. Such models will be much more intuitive if you first learn about the body’s stress response. Third, this chapter has information about health-

New Other Voices feature

Long before psychologists appeared on Earth, the human nature business was dominated by poets, playwrights, pundits, philosophers, and several other groups beginning with P. Those folks are still in that business today, and they continue to have deep and original insights into how and why people behave as they do. In this edition, we decided to invite some of them to share their thoughts with you via a new feature that we call Other Voices. In every chapter, you will find a short essay by someone who has three critical qualities: (a) They think deeply, (b) they write beautifully, and (c) they know things we do not. For example, you will find essays by leading journalists such as David Brooks, Ted Gup, Tina Rosenberg, David Ewing Duncan, and Lisa Willemse; leading educators such as Robert Rothon; renowned legal scholar Elyn Saks; and eminent scientists such as biologist Greg Hampikian and computer scientist Daphne Koller. And just to make sure we are not the only psychologists whose voices you hear, we have included essays by Tim Wilson, Chris Chabris, Daniel Simons, V. S. Ramachandran, Stephen Porter, and Charles Fernyhough. Every one of these amazing people has something important to say about human nature, and we are delighted that they have agreed to say it in these pages. Not only do these essays encourage students to think critically about a variety of psychological issues, but they also demonstrate both the relevance of psychology to everyday life and the growing importance of our science in the public forum.

|

Chapter Number |

Other Voices |

|---|---|

|

1 |

Is Psychology a Science?, p. 17 |

|

2 |

Can We Afford Science?, p. 75 |

|

3 |

Neuromyths, p. 124 |

|

4 |

Hallucinations and the Visual System, p. 156 |

|

5 |

The Blink of an Eye, p. 217 |

|

6 |

Early Memories, p. 261 |

|

7 |

Online Learning, p. 308 |

|

8 |

I Used to Get Invited to Poker Games …, p. 329 |

|

9 |

Canada’s Future Has to Be Bilingual, p. 364 |

|

10 |

How Science Can Build a Better You, p. 421 |

|

11 |

Men, Who Needs Them?, p. 429 |

|

11 |

You Are Going to Die, p. 467 |

|

12 |

Does the Study of Personality Lack … Personality?, p. 503 |

|

13 |

91% of All Students Read This Box and Love It, p. 531 |

|

14 |

False Hopes and Overwhelming Urges, p. 579 |

|

15 |

Successful and Schizophrenic, p. 613 |

|

16 |

Diagnosis: Human, p. 653 |

New Changing Minds questions

What can 784 introductory psychology professors agree about? They can agree that students usually come into their first psychology class with a set of beliefs about the field and that most of these beliefs are wrong. With the help of the wonderful people at Worth Publishers (they made us say that), we conducted a survey of 784 introductory psychology teachers and asked them to name their students’ most common misconceptions about psychology. We then created the Changing Minds questions you will see at the end of every chapter. These questions ask you first to think about an everyday situation in which a common misconception might arise, and then to use the science you have just learned to overcome that misconception. We hope these exercises will prepare you to apply what you learn—

Additional Student Support

101.5.0.0.1 Practice

Cue questions encourage critical thinking and help identify the most important concepts in every major section of the text.

Bulleted summaries follow each major section to reinforce key concepts and make it easier to study for the test.

Page xxiiiA Key Concept Quiz at the end of each chapter offers students the opportunity to test what they know.

Critical thinking questions are offered throughout the chapters within a number of the photograph captions, offering the opportunity to apply various concepts.

101.5.0.0.2 Practical Application

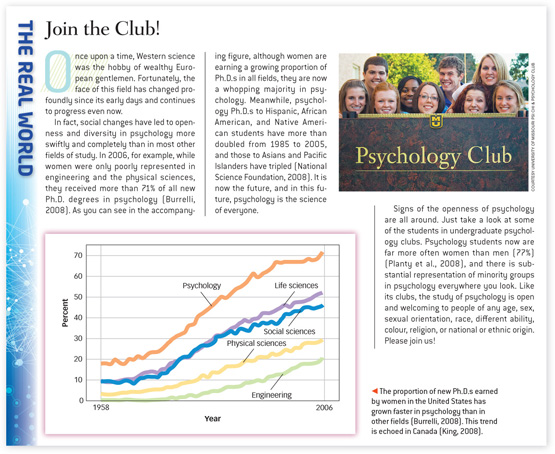

What would the facts and concepts of psychology be without real-

|

Chapter Number |

THE REAL WORLD |

|---|---|

|

1 |

The Perils of Procrastination, p. 4 |

|

1 |

Improving Study Skills, p. 10 |

|

2 |

“Oddsly” Enough, p. 61 |

|

3 |

Brain Plasticity and Sensations in Phantom Limbs, p. 104 |

|

3 |

Brain Death and the Vegetative State, p. 123 |

|

4 |

Multitasking, p. 146 |

|

4 |

Music Training: Worth the Time, p. 163 |

|

5 |

Anyone for Tennis?, p. 192 |

|

6 |

Is Google Hurting Our Memories?, p. 248 |

|

7 |

Understanding Drug Overdoses, p. 270 |

|

8 |

Jeet Jet?, p. 338 |

|

9 |

From Zippers to Political Extremism: An Illusion of Understanding, p. 390 |

|

10 |

Look Smart, p. 400 |

|

11 |

Walk This Way, p. 442 |

|

12 |

Are There “Male” and “Female” Personalities?, p. 481 |

|

13 |

Making the Move, p. 519 |

|

14 |

This is Your Brain on Placebos, p. 571 |

|

15 |

How Are Mental Disorders Defined and Diagnosed?, p. 592 |

|

16 |

Types of Psychotherapists, p. 630 |

|

16 |

Treating Severe Mental Disorders, p. 647 |

|

Chapter Number |

The Real World |

|---|---|

|

1 |

Analytic and Holistic Styles in Western and Eastern Cultures, p. 30 |

|

2 |

Best Place to Fall on Your Face, p. 45 |

|

4 |

Does Culture Influence Change Blindness?, p. 157 |

|

5 |

What Do Dreams Mean to Us around the World?, p. 203 |

|

6 |

Does Culture Affect Childhood Amnesia?, p. 240 |

|

7 |

Are There Cultural Differences in Reinforcers?, p. 281 |

|

8 |

Is It What You Say or How You Say It?, p. 330 |

|

9 |

Does Culture Influence Optimism Bias?, p. 378 |

|

12 |

Does Your Personality Change According to the Language You Are Speaking or Who You Are Speaking With?, p. 492 |

|

13 |

Free Parking, p. 528 |

|

14 |

Oh Canada, Our (New) Home and (Non- |

|

15 |

What Do Mental Disorders Look Like in Different Parts of the World?, p. 589 |

|

16 |

Treatment of Psychological Disorders around the World, p. 632 |

The Psychology of Men and Women

Aggression and biology, pp. 509–

Alcohol

myopia, pp. 208–

pregnancy, pp. 428–

Attraction, pp. 518–

Beauty standards of, pp. 521–

Biological sex/gender, pp. 453–

Body image, pp. 335–

Child-

attachment and, pp. 443–

day care, pp. 444, 447

Dating, pp. 517–

Dieting, pp. 337–

Eating disorders, pp. 333–

Freud’s views, pp. 13–

Gender and social connectedness, p. 465

Happiness, p. 463

Hormones, pp. 453–

Hostility and heart disease, p. 558

Jealousy, p. 26

Life expectancy, p. 464

Life satisfaction, p. 463

Marriage, pp. 465–

Mating preferences

biological, pp. 517–

cultural, pp. 517–

Menarche, p. 453

Moral development, pp. 453–

Personality, pp. 479, 481

Pheromones, p. 171

Physical development, pp. 450–

Pregnancy

health of mother and child, pp. 428–

teen, p. 457

Psychological disorders,

depression, p. 602

panic disorder, p. 596

Rape, p. 211

Relationships, pp. 524–

Sex

avoiding risks, p. 340

motivation for, pp. 339–

and teens, pp. 338–

Social connectedness, pp. 566–

Stereotyping, p. 538

Stress, coping, pp. 561–

Suicide, pp. 621–

Talkativeness, pp. 475–

Women in psychology, pp. 31–

CULTURE and Multicultural Experience

Aggression and culture, pp. 511–

and geography, p. 511

groups, p. 514

Aging population, pp. 460–

Alcohol, binge drinking, p. 209

Attachment style, pp. 444–

Attractiveness, p. 520

Autism, pp. 439, 614–

Body ideal, p. 521

Brain death, p. 123

Conformity, pp. 528–

Cultural norms, pp. 528–

Cultural psychology,

definition, pp. 28–

Culture, discovering, pp. 440–

Deaf culture, pp. 356, 439

Depression, pp. 601–

Development

adolescence, protracted, pp. 453–

attachment, pp. 443–

child-

cognitive development, pp. 433–

counting ability, p. 440

moral development, pp. 446–

Dreams, meaning of, pp. 201–

Drugs, psychological effects of, pp. 646–

Eating disorders, pp. 335–

Expression, display rules, p. 326

Expression, universality, pp. 323–

False memories, pp. 255–

Family therapy, p. 643

Freedom, p. 528

Helpfulness, p. 45

Homosexuality

genes, p. 456

pheromones, p. 171

views on, pp. 455–

Hunger, pp. 334–

Implicit learning, aging, p. 302

Intelligence, pp. 406–

age, pp. 410–

cultural aspects, pp. 406–

education on, pp. 414–

generational, pp. 412–

socioeconomic factors and, pp. 399–

testing bias, pp. 417–

Intrinsic motivation, p. 442

Language

bilingualism, pp. 363–

memory retrieval, p. 236

and personality, pp. 491–

structure, pp. 353–

and thought, pp. 367–

Life expectancy, p. 465

Marijuana laws, pp. 213–

Marriage, pp. 524–

Mating preferences, pp. 518–

Minorities in psychology, pp. 31–

Movie violence, p. 64

Norms, pp. 528–

Obesity, p. 577

Observational learning, pp. 295–

Parent and peer relationships, pp. 458–

Perceptual illusions, pp. 20–

Prejudice and stereotyping, p. 28

Psychoanalysis, pp. 634–

Psychological disorders

antisocial personality disorder, pp. 619–

eating disorders, pp. 335–

outlook on in different cultures, pp. 585, 589

schizophrenia, pp. 607–

Psychotherapy, p. 633

Racism

civil rights, p. 28

stress, p. 552

Reasoning, p. 388

Research ethics, pp. 70–

Sensory branding, p. 129

Stereotype threat, p. 541

Stereotyping, p. 538

Stress

adjusting to a new culture, p. 566

chronic, p. 552

poverty and inequality, p. 557

Subliminal perception, p. 191

Suicide, pp. 621–

Taste preference, pp. 170–

Teen pregnancy, p. 457

Threat reaction, p. 559

Tone of voice and meaning, p. 330

Preparing for the MCAT 2015

A complete correlation of the MCAT psychology topics with this book’s contents is available for download from the Resources area of LaunchPad at http:/

|

MCAT 2015: Categories in Sensation and Perception |

SGWNJ, Psychology, Third Canadian Edition, Correlations |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Content Category 6A: Sensing the environment |

Section Title |

Page Number(s) |

|

Sensory Processing |

Sensation and Perception |

129– |

|

Sensation |

Sensation and Perception |

129– |

|

• Thresholds |

Measuring Thresholds |

132– |

|

• Weber’s Law |

Measuring Thresholds |

132– |

|

• Signal detection theory |

Signal Detection |

133– |

|

• Sensory adaptation |

Sensory Adaptation |

134– |

|

• Sensory receptors |

Sensation and Perception Are Distinct Activities |

130– |

|

• Sensory pathways |

The Visual Brain |

141– |

|

|

Touch and Pain |

164– |

|

|

Body Position, Movement, and Balance |

167 |

|

|

Smell and Taste |

168– |

|

• Types of sensory receptors |

Vision I: How the Eyes and the Brain Convert Light Waves to Neural Signals |

135– |

|

|

The Human Ear |

158– |

|

|

The Body Senses: More Than Skin Deep |

164– |

|

|

Smell and Taste |

168– |

|

MCAT 2015: Categories in Sensation and Perception |

SGWNJ, Psychology, Third Canadian Edition, Correlations |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Content Category 6A: Sensing the environment |

Section Title |

Page Number(s) |

|

Vision |

Vision I and Vision II |

135– |

|

Structure and function of the eye |

The Human Eye |

137– |

|

Visual processing |

Vision I |

135– |

|

• Visual pathways in the brain |

From the Eye to the Brain |

139– |

|

• Parallel processing |

The Visual Brain |

141– |

|

• Feature detection |

Studying the Brain’s Electrical Activity |

118– |

|

|

The Visual Brain |

141– |

|

Hearing |

Audition: More Than Meets the Ear |

157– |

|

Auditory processing |

Perceiving Pitch |

160 |

|

• Auditory pathways in the brain |

Perceiving Pitch |

160 |

|

Sensory reception by hair cells |

The Human Ear |

158– |

|

Other Senses |

The Body Senses: More Than Skin Deep |

163– |

|

|

The Chemical Senses: Adding Flavour |

167– |

|

Somatosensation |

Touch |

164– |

|

• Pain perception |

Pain |

165– |

|

Taste |

Taste |

170– |

|

• Taste buds/chemoreceptors that detect specific chemicals |

Taste |

170– |

|

Smell |

Smell |

168– |

|

• Olfactory cells/chemoreceptors that detect specific chemicals |

Smell |

168– |

|

• Pheromones |

Smell |

171 |

|

• Olfactory pathways in the brain |

Smell |

168– |

|

Kinesthetic sense |

Body Position, Movement, and Balance |

167 |

|

Vestibular sense |

Body Position, Movement, and Balance |

167 |

|

Perception |

Sensation and Perception |

129– |

|

Perception |

Sensation and Perception Are Distinct Activities |

130– |

|

• Bottom- |

Pain |

165– |

|

|

Smell |

168– |

|

• Perceptual organization (e.g., depth, form, motion, constancy) |

Vision II: Recognizing What We Perceive |

144– |

|

• Gestalt principles |

Principles of Perceptual Organization |

148– |

About the Canadian Edition

In writing the Canadian edition, we retained all the unique features of the first American edition textbook, and included the essential and updated coverage of the third American edition. Building on this third edition, our goal was to create a textbook that would engage Canadian students by situating the content in Canadian and international contexts, replacing American examples with those of relevance for both Canadian and other international students. This is why we call it the third Canadian edition. Current Canadian and international data replace American data and statistics where appropriate. We highlight the remarkable scientific accomplishments of Canadian scientists in psychology and neuropsychology, drawing upon Canadian issues. Finally, we have included photographs and figures that reflect the Canadian context and Canadian research.

To illustrate how we have incorporated a Canadian perspective, we highlight some of the specific information included across different chapters.

In our introductory chapter on the evolution of psychology (Chapter 1), we discuss the development of the field in Canada, highlighting Canadian pioneers, such as James Mark Baldwin, Donald Olding Hebb, Brenda Milner, and Wilder Penfield. Besides the American Psychological Association, we include descriptions of other Canadian psychological organizations, such as the Canadian Psychological Association, the Canadian Society for Brain, Behaviour and Cognitive Science, and the Canadian Association of Neuroscience.

Page xxviiIn the chapter on research methods (Chapter 2), we include greater details on the fundamentals of conducting research and data evaluation, using Canadian data in our explanations. Most importantly, we include TriCouncil ethical guidelines, and the Canadian Psychological Association code of ethics that all Canadian psychologists are to follow whether in conducting research or dealing with clients.

When discussing neuroscience and behaviour (Chapter 3), we start with relevant Canadian examples to illustrate the issue of sports-

related head trauma and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. We also highlight the contributions of internationally renowned neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield in mapping the somatosensory and motor cortex. McGill researcher Michael Meaney’s work demonstrating that maternal caretaking behaviour has a profound influence on the stress response in offspring is profiled in the Hot Science box. In Sensation and Perception (Chapter 4), we highlight research from the University of Western Ontario on the neural pathways for vision or visual streams. We also describe University of Toronto researcher Glenn Schellenberg’s study on the link between music education and IQ scores.

In the chapter on consciousness (Chapter 5), we highlight a case study by researchers at the University of Western Ontario who use fMRI technology to determine the level of consciousness in brain-

damaged patients with disorders of consciousness. In Memory (Chapter 6), we cover the seminal research on levels of processing by Fergus Craik and Endel Tulving, from University of Toronto, which has been so influential in our understanding of how humans encode information. In this chapter, we discuss Brenda Milner’s discovery, through her early work with Henry Molaison (H.M.), of the role of the hippocampus in long-

term memory. In the chapter on Learning (Chapter 7), we discuss some of McMaster University researcher Shepard Siegel’s work on classical conditioning and how it can be used to explain how drug overdoses occur with experienced drug abusers. We also describe research at McGill University with rats that demonstrates how operant conditioning occurs.

In Emotion and Motivation (Chapter 8), we discuss the issue of eating disorders from a Canadian perspective and the research of University of British Columbia researcher Stephen Porter on lie detection.

In the chapter on language and thought (Chapter 9), we discuss the future of bilingualism in Canada.

In the chapter on intelligence (Chapter 10), we use athleticism as a model for intelligence, and Canadian hockey player, Hayley Wickenheiser, as an example. By examining Wickenheiser’s athletic abilities we question how intelligence is measured and thus discuss in detail intelligence testing and measurement methods. We also describe the work of University of British Columbia researcher Mark Holder on emotional intelligence.

In Development (Chapter 11), we highlight Canadian statistics on health-

related issues. McGill University research sheds light on the relationship between reflexes and motor development. We describe work by Canadian researcher Tomáš Paus that show how areas of the brain develop with age. The chapter on personality (Chapter 12) describes a study by University of British Columbia researchers on personality, language, and behaviour.

Page xxviiiSocial Psychology (Chapter 13) includes research on the frustration-

aggression hypothesis by University Calgary researchers. We also discuss the research conducted at McGill University on attraction and relationship maintenance. Stress and Health (Chapter 14) includes a study on Canadian immigration and health patterns, and statistics relating to health issues.

In the chapter on psychological disorders (Chapter 15), we look at the incidence rates of psychological disorders in Canada. We also look at alternative disorder evaluation protocols.

In Treatment of Psychological Disorders (Chapter 16), we examine treatment rates and strategies available to Canadians and the ethics code for the treatment of patients.

Media and Supplements

LaunchPad with LearningCurve Quizzing

A comprehensive web resource for teaching and learning psychology

LaunchPad combines Worth Publishers’ award-

The design of the LearningCurve quizzing system is based on the latest findings from learning and memory research. It combines adaptive question selection, immediate and valuable feedback, and a gamelike interface to engage students in a learning experience that is unique to them. Each LearningCurve quiz is fully integrated with other resources in LaunchPad through the Personalized Study Plan, so students will be able to review using Worth’s extensive library of videos and activities. And state-

of- the- art question analysis reports allow instructors to track the progress of individual students as well as their class as a whole.  Page xxix

Page xxixNew! Data Visualization Exercises offer students practice in understanding and reasoning about data. In each activity, students interact with a graph or visual display of data and must think like a scientist to answer the accompanying questions. These activities build quantitative reasoning skills and offer a deeper understanding of how science works.

An interactive e-

Book allows students to highlight, bookmark, and scribble in their own notes on the e-Book page, just as they would with a printed textbook. Google- style searching and in- text glossary definitions make the text ready for the digital age. Student Video Activities include more than 100 engaging video modules that instructors can easily assign and customize for student assessment. Videos cover classic experiments, current news footage, and cutting-

edge research, all of which are sure to spark discussion and encourage critical thinking.

PsychInvestigator: Laboratory Learning in Introductory Psychology is a series of activities that model a virtual laboratory and are produced in association with Arthur Kohn, Ph.D., of Dark Blue Morning Productions. Students are introduced to core psychological concepts by a video host and then participate in activities that generate real data and lead to some startling conclusions! Like all activities in LaunchPad, PsychInvestigator activities can be assigned and automatically graded.

The award-

winning tutorials in Tom Ludwig’s (Hope College) PsychSim 5.0 and Concepts in Action provide an interactive, step- by- step introduction to key psychological concepts. The Scientific American Newsfeed delivers weekly articles, podcasts, and news briefs on the very latest developments in psychology from the first name in popular science journalism.

Additional Student Supplements

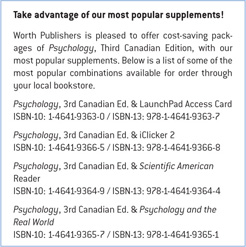

The CourseSmart e-

Book offers the complete text of Psychology, Third Canadian Edition, in an easy-to- use format. Students can choose either to purchase the CourseSmart e- Book as an online subscription or to download it to a personal computer or a portable media player, such as a smart phone or iPad. The CourseSmart e- Book for Psychology, Third Canadian Edition, can be previewed and purchased at www.coursesmart.com. Pursuing Human Strengths: A Positive Psychology Guide by Martin Bolt of Calvin College is a perfect way to introduce students to both the amazing field of positive psychology as well as their own personal strengths.

The Critical Thinking Companion for Introductory Psychology, by Jane S. Halonen of the University of West Florida and Cynthia Gray of Beloit College, contains both a guide to critical thinking strategies as well as exercises in pattern recognition, practical problem solving, creative problem solving, scientific problem solving, psychological reasoning, and perspective-

taking. Worth Publishers is proud to offer several readers of articles taken from the pages of Scientific American. Drawing on award-

winning science journalism, the Scientific American Reader to Accompany Psychology, Third Edition, by Daniel L. Schacter, Daniel T. Gilbert, Daniel M. Wegner, and Matthew K. Nock features pioneering and cutting- edge research across the fields of psychology. Selected by the authors themselves, this collection provides further insight into the fields of psychology through articles written for a popular audience. These articles are available for the Third Canadian Edition. Page xxxPsychology and the Real World: Essays Illustrating Fundamental Contributions to Society is a superb collection of essays by major researchers that describe their landmark studies. Published in association with the not-

for- profit FABBS Foundation, this engaging reader includes Elizabeth Loftus’s own reflections on her study of false memories, Eliot Aronson on his cooperative classroom study, and Daniel Wegner on his study of thought suppression. A portion of all proceeds is donated to FABBS to support societies of cognitive, psychological, behavioural, and brain sciences.

Course Management

Worth Publishers supports multiple Course Management Systems with enhanced cartridges for upload into Blackboard, eCollege, Angel, Desire2Learn, Sakai, and Moodle. Cartridges are provided free upon adoption of Psychology, Third Canadian Edition, and can be downloaded from Worth’s online catalog at www.worthpublishers.com.

Assessment

The Computerized Test Bank powered by Diploma includes a full assortment of test items from author Chad Galuska of the College of Charleston. Each chapter features over 200 multiple-

choice, true/false, and essay questions to test students at several levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. The new edition also features a new set of data- based reasoning questions to test advanced critical thinking skills in a manner similar to the MCAT. All the questions are matched to the outcomes recommended in the 2013 APA Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major. The accompanying grade book software makes it easy to record students’ grades throughout a course, to sort student records, to view detailed analyses of test items, to curve tests, to generate reports, and to add weights to grades. The iClicker Classroom Response System is a versatile polling system developed by educators for educators that makes class time more efficient and interactive. iClicker allows you to ask questions and instantly record your students’ responses, take attendance, and gauge students’ understanding and opinions. iClicker is available at a 10% discount when packaged with Psychology, Third Canadian Edition.

Presentation

Interactive Presentation Slides are another great way to introduce Worth’s dynamic media into the classroom without lots of advance preparation. Each presentation covers a major topic in psychology and integrates Worth’s high quality videos and animations for an engaging teaching and learning experience. These interactive presentations are complimentary to adopters of Psychology, Third Canadian Edition, and are perfect for technology novices and experts alike.

The Instructor’s Resources by Jeffrey Henriques of The University of Wisconsin-

Madison features a variety of materials that are valuable to new and veteran teachers alike. In addition to background on the chapter reading and suggestions for in- class lectures, the manual is rich with activities to engage students in different modes of learning. The Instructor’s Resources can be downloaded at http:/ /www.worthpublishers.com/ .launchpad/ schacter3ecanadian Page xxxi

The Worth Video Anthology for Introductory Psychology includes over 300 unique video clips to bring lectures to life. Provided complimentary to adopters of Psychology, Third Canadian Edition, this rich collection includes clinical footage, interviews, animations, and news segments that vividly illustrate topics across the psychology curriculum.

Faculty Lounge is an online forum provided by Worth Publishers where teachers can find and share favourite teaching ideas and materials, including videos, animations, images, PowerPoint slides, news stories, articles, web links, and lecture activities. Sign up to browse the site or upload your favorite materials for teaching psychology at www.worthpublishers.com/

facultylounge .

Acknowledgments

Despite what you might guess by looking at our photographs, we all found partners who were willing to marry us. We thank Susan McGlynn, Marilynn Oliphant, Keesha Nock, and Mark Wolforth for that particular miracle and also for their love and support during the time when we were busy writing this book.

Although ours are the names on the cover, writing a textbook is a team sport, and we were lucky to have an amazing group of professionals in our dugout. We greatly appreciate the contributions of Martin M. Antony, Mark Baldwin, Michelle A. Butler, Patricia Csank, Denise D. Cummins, Ian J. Deary, Howard Eichenbaum, Sam Gosling, Paul Harris, Catherine Myers, Shigehiro Oishi, Arthur S. Reber, Morgan T. Sammons, Dan Simons, Alan Swinkels, Richard M. Wenzlaff, and Steven Yantis.

We are grateful for the editorial, clerical, and research assistance we received from Molly Evans and Mark Knepley.

In addition, we would like to thank our core supplements authors. They provided insight into the role our book can play in the classroom and adeptly developed the materials to support it. Chad Galuska, Jeff Henriques, and Russ Frohardt, we appreciate your tireless work in the classroom and the experience you brought to the book’s supplements.

We would like to thank the faculty who reviewed the manuscript. These teachers showed a level of engagement we have come to expect from our best colleagues.

For the Canadian edition, we thank:

George Alder

Simon Fraser University

Karen Brebner

St. Francis Xavier University

Stan Cameron

Centennial College

Karla Emeno

University of Ontario Institute of Technology

Gerald Goldberg

York University

Peter Graf

University of British Columbia

Mark Holder

University of British Columbia–

Tru Kwong

Mount Royal University

Laura Loewen

Okanagan College

Michael MacGregor

University of Saskatchewan

Stacey MacKinnon

University of Prince Edward Island

Colleen MacQuarrie

University of Prince Edward Island

Neil McGrenaghan

Humber College

Rick Mehta

Acadia University

Lisa Sinclair

University of Winnipeg

Michael Souza

University of British Columbia

Paul Valliant

Laurentian University

Ena Vukatana

University of Calgary

Bruce Walker

Humber College

Kristian Weihs

Seneca College

Leslie Wright

Dalhousie University

For the American edition, we thank:

Eileen Achorn

University of Texas, San Antonio

Jim Allen

SUNY Geneseo

Randy Arnau

University of Southern Mississippi

Benjamin Bennett-

Oakland University

Stephen Blessing

University of Tampa

Kristin Biondolillo

Arkansas State University

Jeffrey Blum

Los Angeles City College

Richard Bowen

Loyola University of Chicago

Nicole Bragg

Mt. Hood Community College

Jennifer Breneiser

Valdosta State University

Michele Brumley

Idaho State University

Josh Burk

College of William and Mary

Jennifer Butler

Case Western Reserve University

Richard Cavasina

California University of Pennsylvania

Amber Chenoweth

Kent State University

Stephen Chew

Samford University

Chrisanne Christensen

Southern Arkansas University

Sheryl Civjan

Holyoke Community College

Jennifer Dale

Community College of Aurora

Jennifer Daniels

University of Connecticut

Joshua Dobias

University of New Hampshire

Dale Doty

Monroe Community College

Julie Evey-

University of Southern Indiana

Valerie Farmer-

Illinois State University

Diane Feibel

University of Cincinnati, Raymond Walters College

Jocelyn Folk

Kent State University

Chad Galuska

College of Charleston

Afshin Gharib

Dominican University of California

Jeffrey Gibbons

Christopher Newport University

Adam Goodie

University of Georgia

John Governale

Clark College

Patricia Grace

Kaplan University Online

Sarah Grison

University of Illinois at Urbana-

Deletha Hardin

University of Tampa

Jason Hart

Christopher Newport University

Lesley Hathorn

Metropolitan State College of Denver

Mark Hauber

Hunter College

Jacqueline Hembrook

University of New Hampshire

Allen Huffcutt

Bradley University

Mark Hurd

College of Charleston

Linda Jackson

Michigan State University

Jennifer Johnson

Rider University

Lance Jones

Bowling Green State University

Linda Jones

Blinn College

Katherine Judge

Cleveland State University

Don Kates

College of DuPage

Martha Knight-

Warren Wilson College

Ken Koenigshofer

Chaffey College

Neil Kressel

William Patterson University

Josh Landau

York College of Pennsylvania

Fred Leavitt

California State University, East Bay

Tera Letzring

Idaho State University

Karsten Loepelmann

University of Alberta

Ray Lopez

University of Texas at San Antonio

Jeffrey Love

Penn State University

Greg Loviscky

Penn State, University Park

Lynda Mae

Arizona State University at Tempe

Caitlin Mahy

University of Oregon

Gregory Manley

University of Texas at San Antonio

Karen Marsh

University of Minnesota at Duluth

Robert Mather

University of Central Oklahoma

Wanda McCarthy

University of Cincinnati at Clermont College

Daniel McConnell

University of Central Florida

Robert McNally

Austin Community College

Dawn Melzer

Sacred Heart University

Dennis Miller

University of Missouri

Mignon Montpetit

Miami University

Todd Nelson

California State University at Stanislaus

Margaret Norwood

Community College of Aurora

Aminda O’Hare

University of Kansas

Melissa Pace

Kean University

Brady Phelps

South Dakota State University

Raymond Phinney

Wheaton College

Claire St. Peter Pipkin

West Virginia University, Morgantown

Christy Porter

College of William and Mary

Douglas Pruitt

West Kentucky Community and Technical College

Elizabeth Purcell

Greenville Technical College

Gabriel Radvansky

University of Notre Dame

Celia Reaves

Monroe Community College

Diane Reddy

University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

Cynthia Shinabarger Reed

Tarrant County College

David Reetz

Hanover College

Tanya Renner

Kapi’olani Community College

Anthony Robertson

Vancouver Island University

Nancy Rogers

University of Cincinnati

Wendy Rote

University of Rochester

Larry Rudiger

University of Vermont

Sharleen Sakai

Michigan State University

Matthew Sanders

Marquette University

Phillip Schatz

Saint Joseph’s University

Vann Scott

Armstrong Atlantic State University

Colleen Seifert

University of Michigan at Ann Arbor

Wayne Shebilske

Wright State University

Elisabeth Sherwin

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Lisa Shin

Tufts University

Kenith Sobel

University of Central Arkansas

Genevieve Stevens

Houston Community College

Mark Stewart

American River College

Holly Straub

University of South Dakota

Mary Strobbe

San Diego Miramar College

William Struthers

Wheaton College

Lisa Thomassen

Indiana University

Jeremy Tost

Valdosta State University

Laura Turiano

Sacred Heart University

Jeffrey Wagman

Illinois State University

Alexander Williams

University of Kansas

John Wright

Washington State University

Dean Yoshizumi

Sierra College

Keith Young

University of Kansas

We are especially grateful to the extraordinary people of Worth Publishers. They include senior vice president Catherine Woods and publisher Kevin Feyen, who provided guidance and encouragement at all stages of the project; our acquisitions editor, Dan DeBonis, who managed the project with intelligence, grace, and good humour; our development editors, Valerie Raymond and Mimi Melek; director of development for print and digital products Tracey Kuehn; project editor Robert Errera; production manager Sarah Segal; and editorial assistant Katie Garrett, who through some remarkable alchemy turned a manuscript into a book; our art director Babs Reingold; layout designer Paul Lacy; photograph editor Cecilia Varas; and photograph researcher Elyse Rieder, who made that book an aesthetic delight; our media editor Rachel Comerford; and production manager Stacey Alexander, who guided the development and creation of a superb supplements package; our marketing manager Lindsay Johnson; and associate director of market development Carlise Stembridge, who served as tireless public advocates for our vision. For the Canadian edition, we would like to thank the team at First Folio Resource Group Inc. for editorial and production services, and Maria DeCambra & Associates for photograph editing and research. Thank you one and all. We look forward to working with you again.

Daniel L. Schacter

Daniel T. Gilbert

Matthew K. Nock

Ingrid S. Johnsrude