11.4 Adulthood: Change We Cannot Believe In

It takes fewer than 7000 days for a single-

11.4.1 Changing Abilities

The early 20s are the peak years for health, stamina, vigour, and prowess, and because our psychology is so closely tied to our biology, these are also the years during which most of our cognitive abilities are at their sharpest. At this very moment you probably see farther, hear better, remember more, and weigh less than you ever will again. Enjoy it while you can. Your physical peak will last for just a few dozen months more—

HOT SCIENCE: The End of History Illusion

“I have finally arrived.” That is the feeling that many young adults have when they look back at the fast-

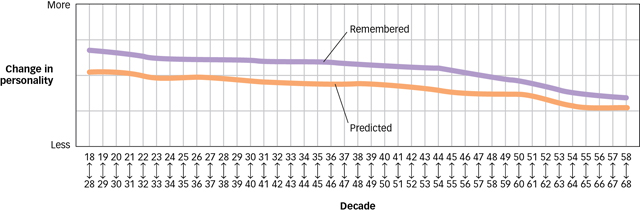

In a recent study (Quoidbach, Gilbert, & Wilson, 2013), researchers asked thousands of people to recall how much their personalities had changed in the last 10 years, or to predict how much their personalities would change in the next 10 years. They then compared the “looking back” memories of people who were a particular age with the “looking forward” predictions of people who were 10 years younger. So, for example, they compared how much 18-

As the graph shows, people who were looking back at a particular decade of life saw much more change than people who were looking forward to it—

Adulthood, it seems, is a period of life that is characterized by unanticipated change, or “change we cannot believe in.” Although both teenagers and their grandparents seem to think that the pace of personal change has slowed to a crawl and that they have finally become the people they will forever be, the data suggest that it simply is not so. Change slows but never stops, and its pace is faster than we expect.

What physical and psychological changes are associated with adulthood?

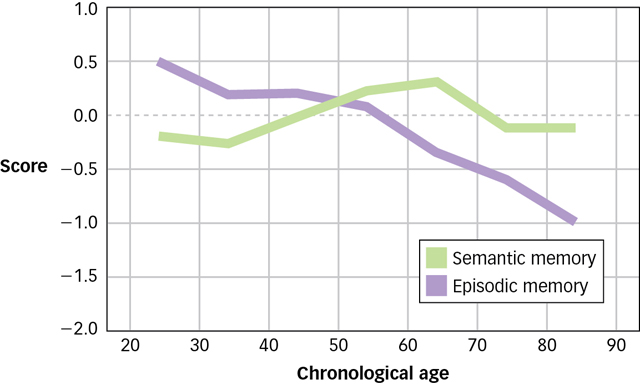

As these physical changes accumulate, they begin to have measurable psychological consequences (Salthouse, 2006) (see FIGURE 11.16). For instance, as your brain ages, your prefrontal cortex and its associated subcortical connections will deteriorate more quickly than the other areas of your brain (Raz, 2000), and you will experience a noticeable decline on cognitive tasks that require effort, initiative, or strategy. Your memory will worsen, though not all kinds will worsen at the same rate. You will experience a greater decline in working memory (the ability to hold information “in mind”) than in long-

How do adults compensate for their declining abilities?

But it is not all bad news. Even though your cognitive machinery will get rustier, research suggests that you will partially compensate by using it much more skillfully (Bäckman & Dixon, 1992; Salthouse, 1987). Older chess players remember chess positions much more poorly than younger players do, but they play just as well because they learn to search the board more efficiently (Charness, 1981). Older typists react more slowly than younger typists do, but they type just as quickly and accurately as because they are better at anticipating the next word in spoken or written text (Salthouse, 1984). There is a good reason that most CEOs, prime ministers, presidents, and other decision makers are over 25. Older airline pilots are considerably worse than younger pilots when it comes to keeping a list of words in short-

Figure 11.16: Cognitive Decline After the age of 20, people show gradual but steady declines on some measures of cognitive performance but not others (Salthouse, 2006). For example, the ability to recall past events (episodic memory) declines as we age, but the ability to recall the meanings of words (semantic memory) does not.

Figure 11.16: Cognitive Decline After the age of 20, people show gradual but steady declines on some measures of cognitive performance but not others (Salthouse, 2006). For example, the ability to recall past events (episodic memory) declines as we age, but the ability to recall the meanings of words (semantic memory) does not.

How do they do that? As you know from the Neuroscience and Behaviour chapter, young brains are highly differentiated, that is, they have different parts that do different things. We now know that as the brain ages it becomes de-

Figure 11.17: Bilaterality in Older and Younger Brains Across a variety of tasks, older adult brains show bilateral activation and young adult brains show unilateral activation. One explanation for this is that older brains compensate for the declining abilities of one neural structure by calling on other neural structures for help (Cabeza, 2002).

Figure 11.17: Bilaterality in Older and Younger Brains Across a variety of tasks, older adult brains show bilateral activation and young adult brains show unilateral activation. One explanation for this is that older brains compensate for the declining abilities of one neural structure by calling on other neural structures for help (Cabeza, 2002).

11.4.2 Changing Goals

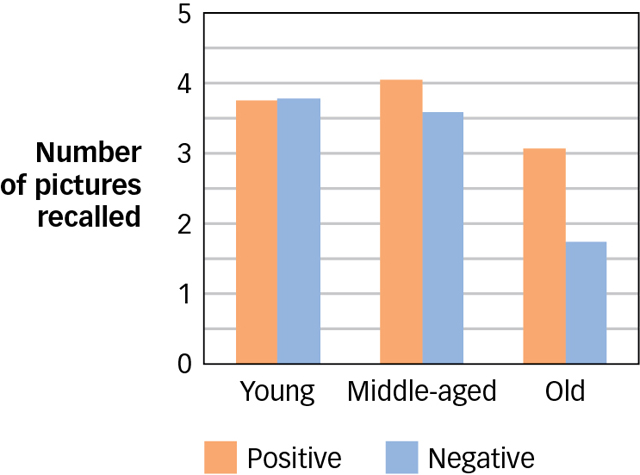

Figure 11.18: Memory for Pictures Memory generally declines with age, but the ability to remember negative information—

Figure 11.18: Memory for Pictures Memory generally declines with age, but the ability to remember negative information—How do informational goals change in adulthood?

One reason why Grandpa cannot find his car keys is that his prefrontal cortex does not work as well as it used to. But another reason is that the location of car keys just is not the sort of thing that grandpas want to spend their precious time memorizing (Haase, Heckhausen, & Wrosch, 2013). According to socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen & Turk-

Is late adulthood a happy or unhappy time for most people?

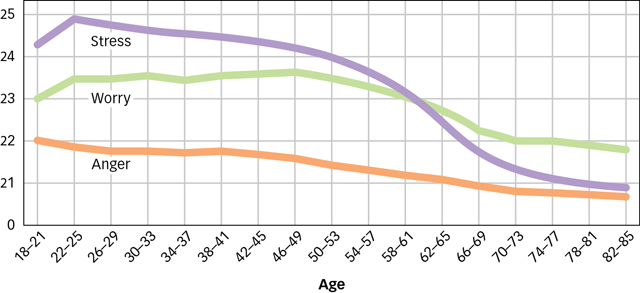

For example, older people perform much more poorly than younger people when they are asked to remember a series of unpleasant faces, but only slightly more poorly when they are asked to remember a series of pleasant faces (Mather & Carstensen, 2003). Whereas younger adults show equal amounts of amygdala activation when they see very pleasant or very unpleasant pictures, older adults show much more activation when they see very pleasant than very unpleasant pictures, suggesting that older adults just are not attending to information that does not make them happy (Mather et al., 2004). Indeed, compared to younger adults, older adults are generally better at sustaining positive emotions and curtailing negative ones (Isaacowitz, 2012; Isaacowitz & Blanchard-

Figure 11.19: Emotions and Age Older adults experience much lower levels of stress, worry, and anger than younger adults do (Stone et al., 2010).

Figure 11.19: Emotions and Age Older adults experience much lower levels of stress, worry, and anger than younger adults do (Stone et al., 2010).

Because having a short future orients people toward emotionally satisfying rather than intellectually profitable experiences, older adults become more selective about their interaction partners, choosing to spend time with family and a few close friends rather than with a large circle of acquaintances. One study monitored a group of people from the 1930s to the 1990s and found that their rate of interaction with acquaintances declined from early to middle adulthood, but their rate of interaction with spouses, parents, and siblings remained stable or increased (Carstensen, 1992). A study of older adults who ranged in age from 69 to 104 found that the oldest adults had fewer peripheral social partners than the younger adults did, but they had just as many emotionally close partners whom they identified as members of their “inner circle” (Lang & Carstensen, 1994). “Let’s go meet some new people” is not something that most 60-

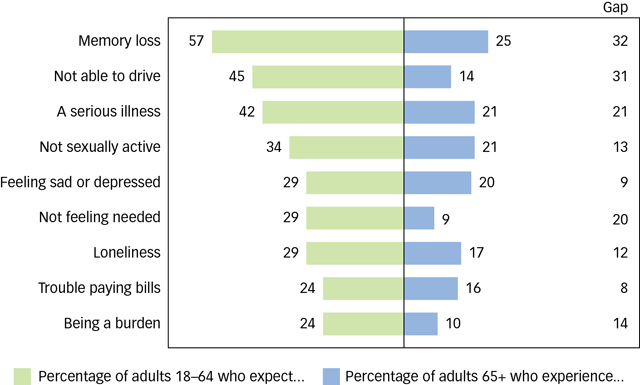

Figure 11.20: It is Better Than You Think Research shows that young adults overestimate the problems of old age (Pew Research Center for People & the Press, 2009).

Figure 11.20: It is Better Than You Think Research shows that young adults overestimate the problems of old age (Pew Research Center for People & the Press, 2009).

11.4.3 Changing Roles

The psychological separation from parents that begins in adolescence usually becomes a physical separation in adulthood. In virtually all human societies, young adults leave home, get married, and have children of their own. Being in a committed long-

What does research say about marriage, children, and happiness?

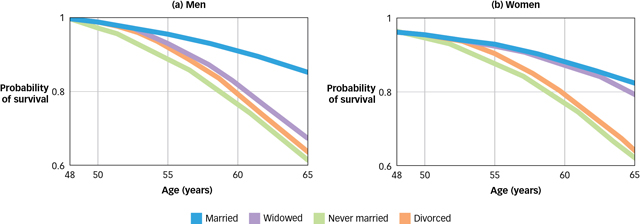

But do marriage and children really make us happy? Research shows that married people live longer (see FIGURE 11.21), have more frequent sex (and enjoy that sex more), and earn several times as much money as unmarried people do (Waite, 1995). Given these differences, it is no surprise that married people report being happier than unmarried people—

Figure 11.21: Til Death Do Us Part Married people live longer than unmarried people, and this is true of both men and women. But while widowed men die as young as never-

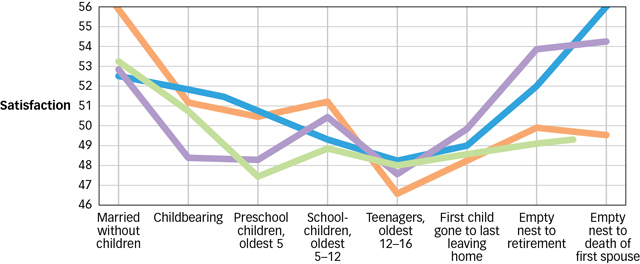

Figure 11.21: Til Death Do Us Part Married people live longer than unmarried people, and this is true of both men and women. But while widowed men die as young as never-Children are another story. In general, research suggests that children do not increase their parents’ happiness, and may even decrease it (DiTella, MacCulloch, & Oswald, 2003; Simon, 2008; Senior, 2014). For example, parents typically report lower marital satisfaction than do nonparents—

Figure 11.22: Marital Satisfaction over the Life Span This graph shows the results of four independent studies of marital satisfaction among men and women. All four studies suggest that marital satisfaction is highest before children are born and after they leave home (Walker, 1977).

Figure 11.22: Marital Satisfaction over the Life Span This graph shows the results of four independent studies of marital satisfaction among men and women. All four studies suggest that marital satisfaction is highest before children are born and after they leave home (Walker, 1977).

Does all of this mean that children cause unhappiness or happiness? Not necessarily. Because researchers cannot randomly assign people to be parents or nonparents, studies of the effects of parenthood are necessarily correlational. What does seem clear is that raising children is a challenging job that most people find especially rewarding when they are not in the middle of doing it.

Older adults show declines in working memory, episodic memory, and retrieval tasks, but they often develop strategies to compensate.

Gradual physical decline begins early in adulthood and has clear psychological consequences, some of which are offset by increases in skill and expertise.

Older people are more oriented toward emotionally satisfying information, which influences their basic cognitive performance, the size and structure of their social networks, and their general happiness.

For most people, adulthood means leaving home, living with a committed long-

term partner, and having children. People with a long- term partner are typically happier, but children and the responsibilities that parenthood entails present a significant challenge, for the first few years of a child’s life, at least.

OTHER VOICES: You Are Going to Die

Human development begins at conception and ends at death. Most of us would rather think about the conception part. Getting old seems scary and depressing, and one of the reasons why we send elderly people to retirement homes may be that we are afraid to watch our loved ones decline. The essayist Tim Kreider (2013) thinks this is a terrible loss—

My sister and I recently toured the retirement community where my mother has announced she will be moving. I have been in some bleak clinical facilities for the elderly where not one person was compos mentis and I had to politely suppress the urge to flee, but this was nothing like that. It was a very cushy modern complex housed in what used to be a seminary, with individual condominiums with big kitchens and sun rooms, equipped with fancy restaurants, grills and snack bars, a fitness centre, a concert hall, a library, an art room, a couple of beauty salons, a bank and an ornate chapel of Italian marble. You could walk from any building in the complex to another without ever going outside, through underground corridors and glass-

At all times of major life crisis, friends and family will crowd around and press upon you the false emotions appropriate to the occasion. “That’s so great!” everyone said of my mother’s decision to move to an assisted-

My sadness is purely selfish, I know. My friends are right; this was all Mom’s idea, she’s looking forward to it, and she really will be happier there. But it also means losing the farm my father bought in 1976, where my sister and I grew up, where Dad died in 1991. We’re losing our old phone number, the one we have had since the Ford administration, a number I know as well as my own middle name. However infrequently I go there, it is the place on earth that feels like home to me, the place I’ll always have to go back to in case adulthood falls through. I hadn’t realized, until I was forcibly divested of it, that I’d been harbouring the idea that someday, when this whole crazy adventure was over, I would at some point be nine again, sitting around the dinner table with Mom and Dad and my sister. And beneath it all, even at age 45, there is the irrational, little-

Plenty of people before me have lamented the way that we in industrialized countries regard our elderly as unproductive workers or obsolete products, and lock them away in institutions instead of taking them into our own homes out of devotion and duty. Most of these critiques are directed at the indifference and cruelty thus displayed to the elderly; what I wonder about is what it’s doing to the rest of us.

Segregating the old and the sick enables a fantasy, as baseless as the fantasy of capitalism’s endless expansion, of youth and health as eternal, in which old age can seem to be an inexplicably bad lifestyle choice, like eating junk food or buying a minivan, that you can avoid if you’re well-

We don’t see old or infirm people much in movies or on TV. We love explosive gory death onscreen, but we’re not so enamored of the creeping, gray, incontinent kind. Aging and death are embarrassing medical conditions, like hemorrhoids or eczema, best kept out of sight. Survivors of serious illness or injuries have written that, once they were sick or disabled, they found themselves confined to a different world, a world of sick people, invisible to the rest of us. Denis Johnson writes in his novel Jesus’ Son: “You and I don’t know about these diseases until we get them, in which case we also will be put out of sight.”

My own father died at home, in what was once my childhood bedroom. He was, in this respect at least, a lucky man. Almost everyone dies in a hospital now, even though absolutely nobody wants to, because by the time we’re dying all the decisions have been taken out of our hands by the well, and the well are without mercy. Of course we hospitalize the sick and the old for some good reasons (better care, pain relief), but I think we also segregate the elderly from the rest of society because we’re afraid of them, as if age might be contagious. Which, it turns out, it is.

… You are older at this moment than you’ve ever been before, and it is the youngest you’re ever going to get. The mortality rate is holding at a scandalous 100 percent. Pretending death can be indefinitely evaded with hot yoga or a gluten-

Just yesterday my mother sent me a poem she first read in college—

Do you agree with Kreider: Do we do a disservice to the young when we segregate the old?

From the New York Times, January 20, 2013. © 2013 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited. http:/