12.4 The Humanistic–Existential Approach: Personality as Choice

In the 1950s and 1960s, psychologists began to try to understand personality from a viewpoint quite different from trait theory’s biological determinism and Freud’s focus on unconscious drives from unresolved childhood experiences. These new humanistic and existential theorists turned attention to how humans make healthy choices that create their personalities. Humanistic psychologists emphasized a positive, optimistic view of human nature that highlights people’s inherent goodness and their potential for personal growth. Existentialist psychologists focused on the individual as a responsible agent who is free to create and live his or her life while negotiating the issue of meaning and the reality of death. The humanistic–

12.4.1 Human Needs and Self-Actualization

What is it to be self-

Humanists see the self-actualizing tendency, the human motive toward realizing our inner potential, as a major factor in personality. The pursuit of knowledge, the expression of one’s creativity, the quest for spiritual enlightenment, and the desire to give to society all are examples of self-

Humanist psychologists explain individual personality differences as arising from the various ways that the environment facilitates—

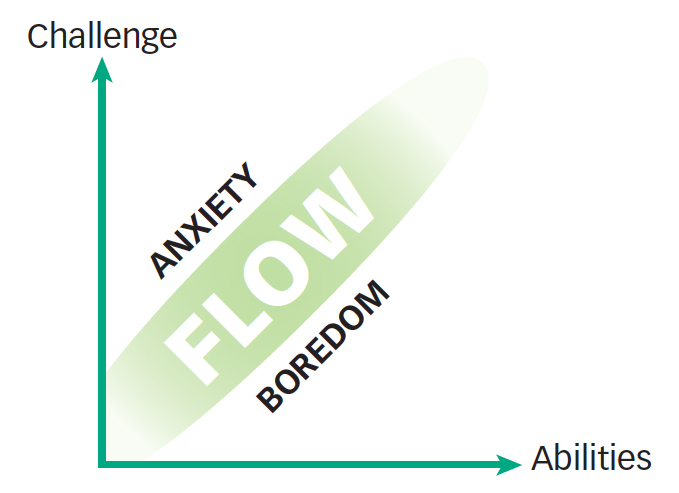

Figure 12.4: Flow Experience It feels good to do things that challenge your abilities but that do not challenge them too much. Csikszentmihalyi (1990) described this feeling between boredom and anxiety as the “flow experience.

Figure 12.4: Flow Experience It feels good to do things that challenge your abilities but that do not challenge them too much. Csikszentmihalyi (1990) described this feeling between boredom and anxiety as the “flow experience.

It feels great to be doing exactly what you are capable of doing. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1990) found that engagement in tasks that exactly match one’s abilities creates a mental state of energized focus that he called flow (see FIGURE 12.4). Tasks that are below our abilities cause boredom, those that are too challenging cause anxiety, and those that are “just right” lead to the experience of flow. If you know how to play the piano, for example, and are playing a Chopin prelude that you know well enough that it just matches your abilities, you are likely to experience this optimal state. People report being happier at these times than at any other times. Humanists believe that such peak experiences, or states of flow, reflect the realization of one’s human potential and represent the height of personality development.

12.4.2 Personality as Existence

Existentialists agree with humanists about many of the features of personality but focus on challenges to the human condition that are more profound than the lack of a nurturing environment. Rollo May (1983) and Victor Frankl (2000), for example, argued that specific aspects of the human condition, such as awareness of our own existence and the ability to make choices about how to behave, have a double-

What is angst, and how is it created?

According to the existential perspective, the difficulties we face in finding meaning in life and in accepting the responsibility of making free choices provoke a type of anxiety existentialists call angst (the anxiety of fully being). The human ability to consider limitless numbers of goals and actions is exhilarating, but it can also open the door to profound questions such as: Why am I here? What is the meaning of my life?

Thinking about the meaning of existence also can evoke an awareness of the inevitability of death. What, then, should we do with each moment? What is the purpose of living if life as we know it will end one day, perhaps even today? Alternatively, does life have more meaning given that it is so temporary? Existential theorists do not suggest that people consider these profound existential issues on a day-

For existentialists, a healthier solution is to face the issues head-

The humanistic–

existential approach to personality grew out of philosophical traditions that are at odds with most of the assumptions of the trait and psychoanalytic approaches. Humanists see personality as directed by an inherent striving toward self-

actualization and development of our unique human potentials. Existentialists focus on angst and the defensive response people often have to questions about the meaning of life and the inevitability of death.