12.5 The Social–Cognitive Approach: Personalities in Situations

What is it like to be a person? The social-cognitive approach views personality in terms of how the person thinks about the situations encountered in daily life and behaves in response to them. Bringing together insights from social psychology, cognitive psychology, and learning theory, this approach emphasizes how the person experiences and interprets situations (Bandura, 1986; Mischel & Shoda, 1999; Ross & Nisbett, 1991; Wegner & Gilbert, 2000).

Do researchers in social cognition think that personality arises from past experiences or from the current environment?

Researchers in social cognition believe that both the current situation and learning history are key determinants of behaviour, and focus on how people perceive their environments. People think about their goals, the consequences of their behaviour, and how they might achieve certain things in different situations (Lewin, 1951). The social–

12.5.1 Consistency of Personality across Situations

Although social–

This controversy began in earnest when Walter Mischel (1968) argued that measured personality traits often do a poor job of predicting individuals’ behaviour. Mischel reviewed decades of research that compared scores on standard personality tests with actual behaviour, looking at evidence from studies asking questions such as “Does a person with a high score on a test of introversion actually spend more time alone than someone with a low score?” Mischel’s disturbing conclusion: The average correlation between trait and behaviour is only about 0.30. This is certainly better than zero (i.e., no relation at all) but not very good when you remember that a perfect prediction is represented by a correlation of 1.0.

Mischel also noted that knowing how a person will behave in one situation is not particularly helpful in predicting the person’s behaviour in another situation. For example, in classic studies, Hugh Hartshorne and Mark May (1928) assessed children’s honesty by examining their willingness to cheat on a test and found that such dishonesty was not consistent from one situation to another. The assessment of a child’s trait of honesty in a cheating situation was of almost no use in predicting whether the child would act honestly in a different situation, such as when given the opportunity to steal money. Mischel proposed that measured traits do not predict behaviours very well because behaviours are determined more by situational factors than personality theorists were willing to acknowledge.

Does personality or the current situation predict a person’s behaviour?

Is there no personality, then? Do we all just do what situations require? The person–

12.5.2 Personal Constructs

Why does everyone not love clowns?

How can we understand differences in the way situations are interpreted? Recall our notion of personality often existing in the eye of the beholder. Situations may exist in the eye of the beholder as well. One person’s gold mine may be another person’s useless hole in the ground. George Kelly (1955) long ago realized that these differences in perspective could be used to understand the perceiver’s personality. He suggested that people view the social world from differing perspectives and that these different views arise through the application of personal constructs, dimensions people use in making sense of their experiences. Consider, for example, different individuals’ personal constructs of a clown: One person may see him as a source of fun, another as a tragic figure, and yet another as so frightening that McDonald’s must be avoided at all costs.

CULTURE & COMMUNITY

Does Your Personality Change According to Which Language You Are Speaking, or Who You are Speaking With?

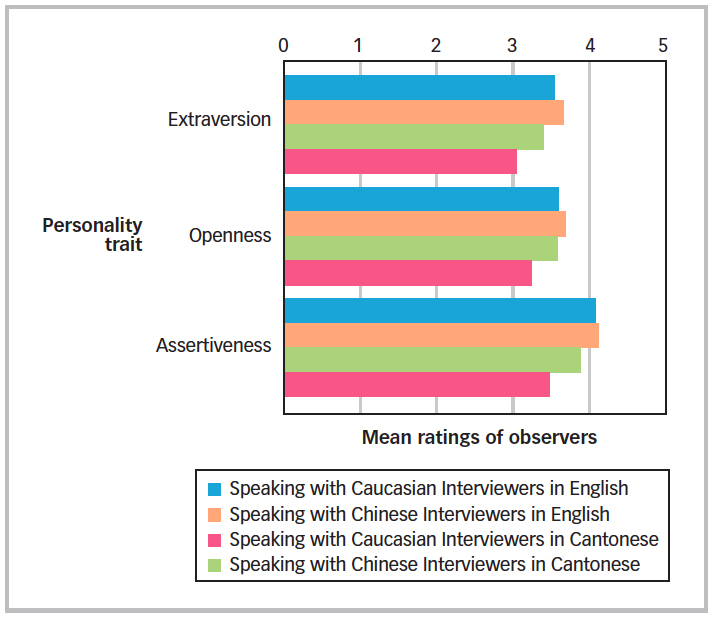

The personalities of people from different cultures can often diverge. For instance, Cantonese–

Such students were interviewed in four conditions: talking with a Caucasian interviewer in English, with the same interviewer in Cantonese, with a Chinese interviewer in English, and with that interviewer in Cantonese. Two different Caucasian and two different Chinese interviewers were used to control for interviewer effects, and all interviews were conducted from scripts (counterbalanced across conditions). In all the interviews, participants answered general information questions about themselves, their hobbies, and their social activities. All interviewers wore the same clothing and were trained to standardize their language and nonverbal behaviours. The four interviews with each participant were recorded (only the participant, not interviewer, was visible). The videos were observed by two Cantonese–

Observers ratings depended both on the language in which people were speaking and on the ethnicity of the interviewer. Participants were rated as substantially less extraverted, open to experience, and assertive when the participants were speaking with a Chinese interviewer in Cantonese than when they were speaking with a Caucasian interviewer in either language. When participants spoke with a Chinese interviewer in English, ratings were somewhat lower than when speaking with a Caucasian interviewer, but still higher than when speaking Cantonese with a Chinese interviewer. These results suggest that bilinguals, when they interact with people from different cultures, exhibit personality traits that correspond to their perceptions of “typical” personality in those cultures.

Kelly assessed personal constructs about social relationships by asking people to (1) list the people in their life, (2) consider three of the people and state a way in which two of them are similar to each other and different from the third, and (3) repeat this for other triads of people to produce a list of the dimensions used to classify friends and family. One respondent might focus on the degree to which people (self included) are lazy or hardworking, for example; someone else might attend to the degree to which people are sociable or unfriendly.

Kelly proposed that different personal constructs (construals) are the key to personality differences; that is, different construals lead people to engage in different behaviours. Taking a long break from work for a leisurely lunch might seem lazy to you. To your friend, the break might seem an ideal opportunity to catch up with friends and she or he may wonder why you always choose to eat at your desk. Social–

12.5.3 Personal Goals and Expectancies

Social–

People translate goals into behaviour in part through outcome expectancies, a person’s assumptions about the likely consequences of a future behaviour. Just as a laboratory rat learns that pressing a bar releases a food pellet, we learn that “if I am friendly toward people, they will be friendly in return,” and “if I ask people to pull my finger, they will withdraw from me.” So we learn to perform behaviours that we expect will have the outcome of moving us closer to our goals. Outcome expectancies are learned through direct experience, both bitter and sweet, and through merely observing other people’s actions and their consequences.

Outcome expectancies combine with a person’s goals to produce the person’s characteristic style of behaviour. An individual with the goal of making friends and the expectancy that being kind will produce warmth in return is likely to behave very differently from an individual whose goal is to achieve fame at any cost and who believes that shameless self-

What is the advantage of an internal locus of control?

People differ in their generalized expectancy for achieving goals. Some people seem to feel that they are fully in control of what happens to them in life, whereas others feel that the world doles out rewards and punishments to them irrespective of their actions. Julian Rotter (1966) developed a questionnaire (see TABLE 12.5) to measure a person’s tendency to perceive the control of rewards as internal to the self or external in the environment, a disposition he called locus of control. People whose answers suggest that they believe they control their own destiny are said to have an internal locus of control, whereas those who believe that outcomes are random, determined by luck, or controlled by other people are described as having an external locus of control. These beliefs translate into individual differences in emotion and behaviour. For example, people with an internal locus of control tend to be less anxious, achieve more, and cope better with stress than do people with an external orientation (Lefcourt, 1982). To get a sense of your standing on this trait dimension, choose one of the options for each of the sample items from the locus-

| For each pair of items, choose the option that most closely reflects your personal belief. Then check the answer key below to see if you have more of an internal or external locus of control. | |

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

|

Source: Rotter, 1966. Answers: A more internal locus of control would be reflected in choosing options 1b, 2b, 3a, and 4a. |

|

The social–

cognitive approach focuses on personality as arising from individuals’ behaviour in situations. Situations mean different things to different people, as suggested by Kelly’s personal construct theory. According to social–

cognitive personality theorists, the same person may behave differently in different situations but should behave consistently in similar situations. People translate their goals into behaviour through outcome expectancies, their assumptions about the likely consequences of future behaviours.