12.6 The Self: Personality in the Mirror

Imagine that you wake up tomorrow morning, drag yourself into the bathroom, look into the mirror, and do not recognize the face looking back at you. This was the plight of a patient studied by neurologist Todd Feinberg (2001). The woman, married for 30 years and the mother of two grown children, one day began to respond to her mirror image as if it were a different person. She talked to and challenged the person in the mirror. When there was no response, she tried to attack it as if it were an intruder. Her husband, shaken by this bizarre behaviour, brought her to the neurologist, who was gradually able to convince her that the image in the mirror was in fact herself.

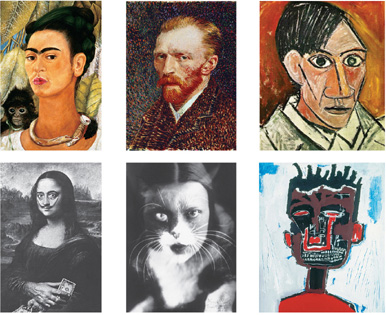

Most of us are pretty familiar with the face that looks back at us from every mirror. We develop the ability to recognize ourselves in mirrors by 18 months of age (as discussed in the Consciousness chapter), and we share this skill with chimpanzees and other apes that have been raised in the presence of mirrors. Self-

Admittedly, none of us know all there is to know about our own personality. In fact, sometimes others may know us better than we know ourselves (Vazire & Mehl, 2008). But we do have enough self-

12.6.1 Self-Concept

Explain the difference between I and Me.

In his renowned psychology textbook, William James (1890) included a theory of self in which he pointed to the self’s two facets, the I and the Me. The I is the self that thinks, experiences, and acts in the world; it is the self as a knower. The Me is the self that is an object in the world; it is the self that is known. The I is much like consciousness, then, a perspective on all of experience (see the Consciousness chapter), but the Me is less mysterious: It is just a concept of a person.

If asked to describe your Me, you might mention your physical characteristics (male or female, tall or short, dark-

12.6.1.1 Self-Concept Organization

Almost everyone has a place for memorabilia, a drawer or box somewhere that holds all those sentimental keepsakes—

What is your life story as you see it—

The aspect of the self-

Self-

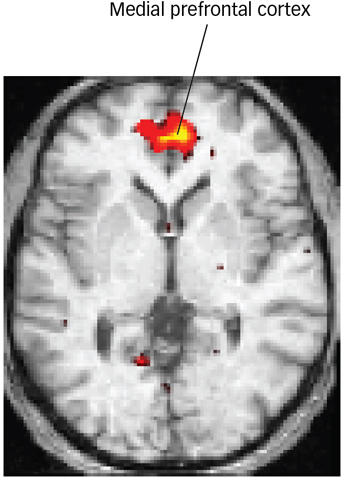

Research also shows that the traits people use to judge the self tend to stick in memory. When people make judgments of themselves on traits, they later recall the traits better than when they judge other people on the same traits (Rogers, Kuiper, & Kirker, 1977). For example, answering a question such as “Are you generous?”—no matter what your answer—

Figure 12.5: Self-

Figure 12.5: Self-Why do traits not always reflect knowledge of behaviour?

How do our behaviour self-

12.6.1.2 Causes and Effects of Self-Concept

How do self-

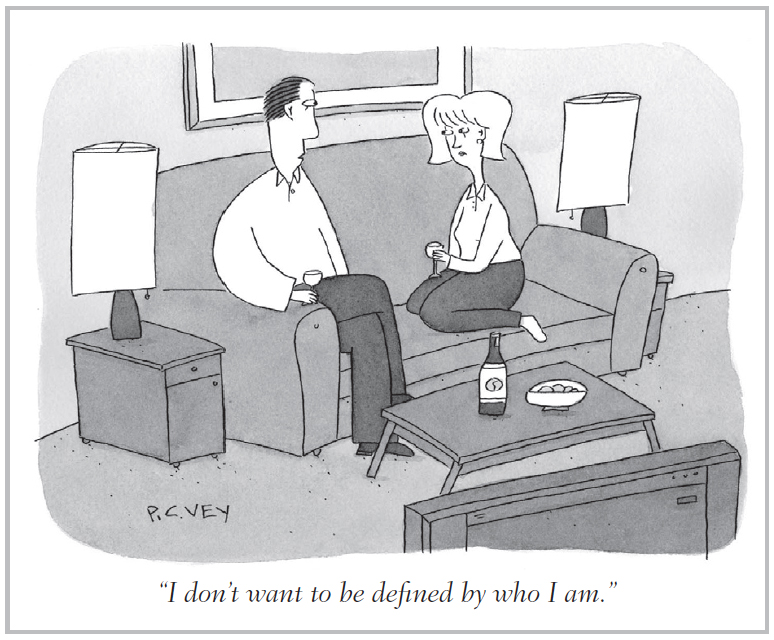

Over the course of a lifetime, however, we become less and less impressed with what others have to say about us. Social theorist George Herbert Mead (1934) observed that all the things people have said about us accumulate after a while into what we see as a kind of consensus held by the “generalized other.” We typically adopt this general view of ourselves and hold on to it stubbornly. As a result, the person who says you are a jerk may upset you momentarily, but you bounce back, secure in the knowledge that you actually are not a jerk. And just as we might argue vehemently with someone who tried to tell us a refrigerator is a pair of underpants, we are likely to defend our self-

How does self-

Because it is so stable, a major effect of the self-

12.6.2 Self-Esteem

When you think about yourself, do you feel good and worthy? Do you like yourself, or do you feel bad and have negative, self-

|

1. On the whole, I am satisfied with myself. |

SA |

A |

D |

SD |

|

2. At times, I think I am no good at all. |

SA |

A |

D |

SD |

|

3. I feel that I have a number of good qualities. |

SA |

A |

D |

SD |

|

4. I am able to do things as well as most other people. |

SA |

A |

D |

SD |

|

5. I feel I do not have much to be proud of. |

SA |

A |

D |

SD |

|

6. I certainly feel useless at times. |

SA |

A |

D |

SD |

|

7. I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others. |

SA |

A |

D |

SD |

|

8. I wish I could have more respect for myself. |

SA |

A |

D |

SD |

|

9. All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure. |

SA |

A |

D |

SD |

|

10. I take a positive attitude toward myself. |

SA |

A |

D |

SD |

|

Source: Rosenberg, 1965. Scoring: For items 1, 3, 4, 7, and 10, SA = 3, A = 2, D = 1, SD = 0; for items 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9, the scoring is reversed, with SA = 0, A = 1, D = 2, SD = 3. The higher the total score, the higher one’s self- |

||||

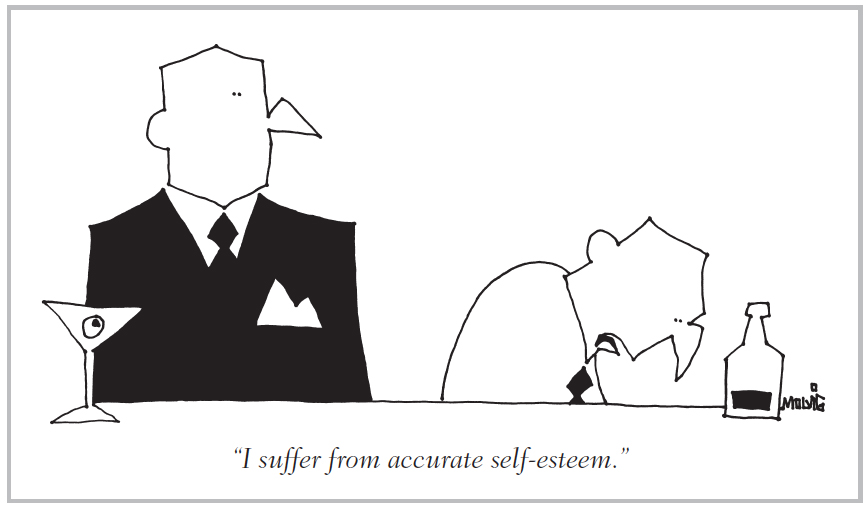

Although some personality psychologists have argued that self-

12.6.2.1 Sources of Self-Esteem

Some psychologists contend that high self-

How do comparisons with others affect self-

An important factor is whom people choose for comparison. For example, James (1890) noted that an accomplished athlete who is the second best in the world should feel pretty proud, but this athlete might not if the standard of comparison involves being best in the world. In fact, athletes in the 1992 Olympics who had won silver medals looked less happy during the medal ceremony than those who had won bronze medals (Medvec, Madey, & Gilovich, 1995). If the actual self is seen as falling short of the ideal self (the person that they would like to be) people tend to feel sad or dejected; when they become aware that the actual self is inconsistent with the self they have a duty to be, they are likely to feel anxious or agitated (Higgins, 1987).

Unconscious perspectives we take on feedback can also affect our sense of self-

Self-

12.6.2.2 The Desire for Self-Esteem

What is so great about self-

Does self-

How might self-

Could the desire for self-

The idea that self-

Whatever the reason that low self-

What is the relationship between self-

On the whole, most people satisfy the desire for high self-

On the other hand, a few people take positive self-

12.6.2.3 Implicit Egotism

What is your favourite letter of the alphabet? About 30 percent of people answer by picking what just happens to be the first letter of their first name. Could this choice indicate that some people think so highly of themselves that they base judgments of seemingly unrelated topics on how much it reminds them of themselves?

Do people choose homes and occupations based in part on their own names?

This name-

These biases have been called expressions of implicit egotism because people are not typically aware that they are influenced by the wonderful sound of their own names (Pelham, Carvallo, & Jones, 2005). When Regina moves to Regina, she is not likely to volunteer that she did so because it matched her name. Yet people who show this egotistic bias in one way also tend to show it in others: People who strongly prefer their own name letter also are likely to pick their birth date as their favourite number (Koole, Dijksterhuis, & van Knippenberg, 2001). And people who like their name letter were also found to evaluate themselves positively on self-

At some level, of course, a bit of egotism is probably good for us. It is sad to meet someone who hates her own name or whose snap judgment of self is “I am worthless.” Yet in another sense, implicit egotism is a curiously subtle error: a tendency to make biased judgments of what we will do and where we will go in life just because we happen to have a certain name. Yes, the bias is only a small one. But your authors wonder: Could we have found better people to work with had we not fallen prey to this bias in our choice of colleagues? The first three authors (Dan, Dan, and Dan) thought they were breaking this cycle by adding a non-

The self is the part of personality that the person knows and can report about. Some of the personality measures we have seen in this chapter (such as personality inventories based on self-

The self-

concept is a person’s knowledge of self, including both specific self- narratives and more abstract personality traits or self- schemas. People’s self-

concept develops through social feedback, and people often act to try to confirm these views through a process of self- verification. Page 503Self-

esteem is a person’s evaluation of self; it is derived from being accepted by others, as well as by how we evaluate ourselves by comparison to others. Theories proposed to explain why we seek positive self- esteem suggest that we do so to achieve perceptions of status, or belonging, or of being symbolically protected against mortality. People strive for positive self-

views through self- serving biases and implicit egotism.

OTHER VOICES: Does the Study of Personality Lack…Personality?

As described in this chapter, some of the field’s older ideas about personality (such as those in the sections on psychodynamic and humanistic–

… In the twentieth century, psychoanalysts were a big deal. There were a number of best-

When it comes to treating mental illness, I guess I am glad we have made this shift. I put more faith in medications and cognitive therapies than in Freudian or Jungian analysis. But something has been lost as well as gained. We are less adept at talking about personalities and neuroses than we were when psychoanalysts held center stage.

For example, in the middle of the twentieth century, a woman named Karen Horney (pronounced HOR-

Some people respond to their wounds by moving against others. These domineering types seek to establish security by conquering and outperforming other people. They deny their own weaknesses. They are rarely plagued by self-

Other people respond to anxiety by moving toward others. These dependent types try to win people’s affections by being compliant. They avoid conflict. They become absorbed by their relationships, surrendering their individual opinions. They regard everyone else as essentially good, even people who have been cruel. …

Other people move away from others. These detached types try to isolate themselves and adopt an onlooker’s attitude toward life. As Terry D. Cooper summarizes the category in his book, Sin, Pride and Self-

The domineering person believes that, if he wins life’s battles, nothing can hurt him. The dependent person believes that, if he shuns private gain and conforms to the wishes of others, then the world will treat him nicely. The detached person believes that, if he asks nothing of the world, the world will ask nothing of him. These are ideal types, obviously, conceptual categories. They join a profusion of personality types that were churned out by various writers in the mid-

The books that explained these theories were good bad books. The good bad book (I am deriving the category from a phrase from Orwell) makes sweeping claims, and lumps people into big groups. Sometimes these claims are not really defensible intellectually. But they are thought-

We are probably poorer now that people like Horney have sunk to near oblivion—

Is David Brooks right? The study of personality has been away from big picture explanations like those of Freud, Maslow, and Frankl, which attempt to explain why we behave the way we do with one overarching theory, and toward efforts to break down personality into smaller constructs and understand how nature and nurture produce these core traits. But have we actually gotten worse at understanding personality? On balance, should interesting theories that make intriguing assumptions about people’s personalities, but have no data to support their accuracy, be retained simply because they tell a more interesting story? If you are reading this book, you represent the future of psychology. How can we better understand and measure human personality? What are the most important future steps?

From the New York Times, October 12, 2012 © 2012 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited. http:/