13.2 Social Influence: Controlling People

Those of us who grew up watching cartoons on Saturday mornings have usually thought a bit about which of the standard superpowers we would most like to have. Super strength and super speed have obvious benefits, invisibility and X-

Social influence is the ability to control another person’s behaviour (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004). But how does it work? If you want someone to give you their time, money, allegiance, or affection, you would be wise to consider first what it is they want. People have three basic motivations that make them susceptible to social influence (Bargh, Gollwitzer, & Oettingen, 2010; Fiske, 2010). First, people are motivated to experience pleasure and to avoid experiencing pain (the hedonic motive). Second, people are motivated to be accepted and to avoid being rejected (the approval motive). Third, people are motivated to believe what is right and to avoid believing what is wrong (the accuracy motive). As you will see, most social influence attempts appeal to one or more of these motives.

13.2.1 The Hedonic Motive: Pleasure Is Better Than Pain

How effective are rewards and punishments?

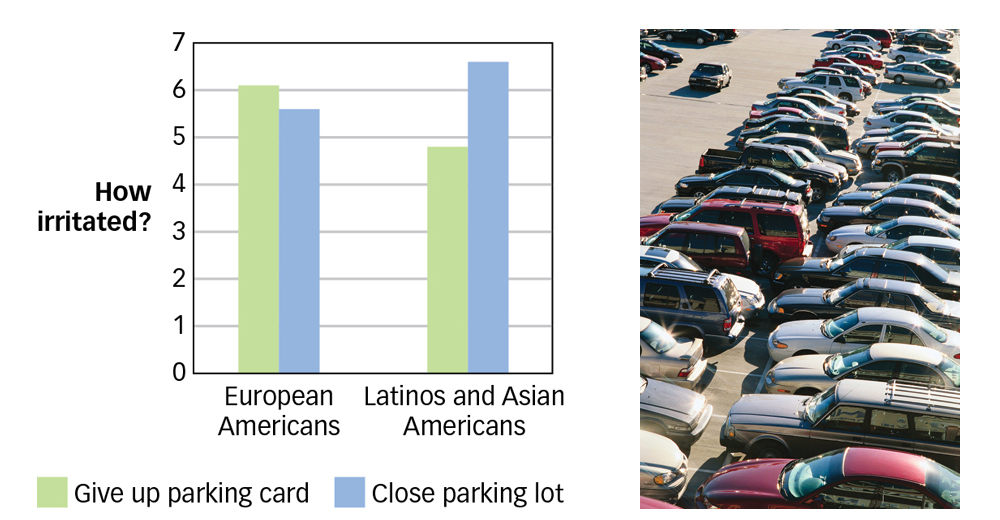

If there is an animal that prefers pain to pleasure it must be very good at hiding because no one has ever seen it. Pleasure seeking is the most basic of all motives, and social influence often involves creating situations in which others can achieve more pleasure by doing what we want them to do than by doing something else. Parents, teachers, governments, and businesses influence our behaviour by offering rewards and threatening punishments (see FIGURE 13.8). There is nothing mysterious about how these influence attempts work, and they are often quite effective. When the Republic of Singapore warned its citizens that anyone caught chewing gum in public would face a year in prison and a $5500 fine, the rest of the world was outraged; but when the outrage subsided, it was hard to ignore the fact that gum chewing in Singapore had fallen to an all-

You will recall from the Memory chapter that even a sea slug will repeat behaviours that are followed by rewards and avoid behaviours that are followed by punishments. Although the same is generally true of human beings, there are some instances in which rewards and punishments can backfire. For example, children in one study were allowed to play with coloured markers and then some were given a “Good Player Award.” When the children were given markers the next day, those who had received an award were less likely to play with them than were those who had not received an award (Lepper, Greene, & Nisbett, 1973). Why? Because children who had received an award the first day came to think of drawing as something one does to receive rewards, and if no one was going to give them an award, then why the heck should they do it (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999)? Similarly, rewards and punishments can backfire simply because people do not like being manipulated with them. Researchers placed signs in two restrooms on a university campus: “Please do not write on these walls” and “Do not write on these walls under any circumstances.” Two weeks later, the walls in the second restroom had more graffiti on the walls, presumably because students did not appreciate the threatening tone of the second sign and wrote on the walls just to prove that they could (Pennebaker & Sanders, 1976).

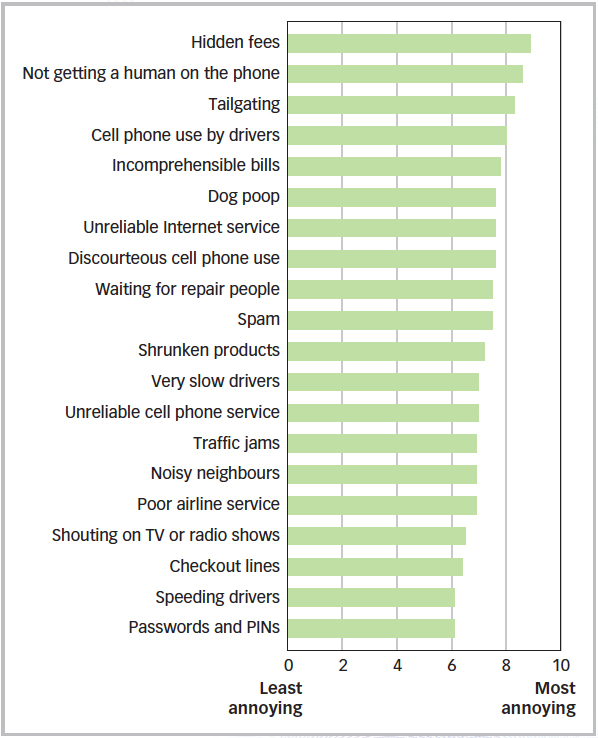

Figure 13.8: The Cost of Speeding The penalty for speeding in Massachusetts used to be a modest fine. In 2006, the legislature changed the law so that drivers under 18 who are caught speeding now lose their licenses for 90 days—

Figure 13.8: The Cost of Speeding The penalty for speeding in Massachusetts used to be a modest fine. In 2006, the legislature changed the law so that drivers under 18 who are caught speeding now lose their licenses for 90 days—CULTURE & COMMUNITY: Free Parking

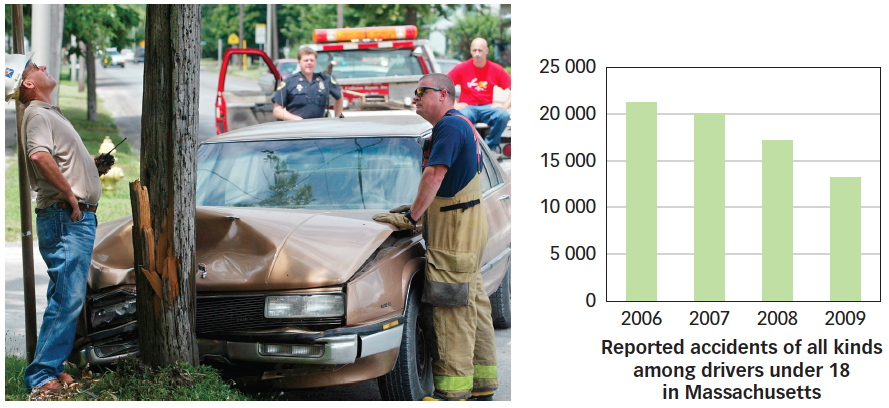

People do not like to be manipulated, and they get upset when someone threatens their freedom to do as they wish. Is this a uniquely Western reaction? To find out, psychologist Eva Jonas and her colleagues asked American university students one of two favours and then measured how irritated they felt (Jonas et al., 2009). In one case, they asked students if they would give up their right to park on campus for a week (“Would you mind if I used your parking card so I can participate in a research project in this building?”). In the other case, they asked students if they would give up everyone’s right to park on campus for a week (“Would you mind if we closed the entire parking lot for a tennis tournament?”). How did students react to these requests?

It depended on their culture. As the figure shows, European American students were more irritated by a request that limited their freedom than by a request that limited everyone’s freedom (“If nobody can park, that’s inconvenient. But if everybody except me can park, that’s unfair!”). But Latino and Asian American students had precisely the opposite reactions (“The needs of the requestor outweigh the needs of one student, but they do not outweigh the needs of all students”). It appears that people do indeed value freedom—

13.2.2 The Approval Motive: Acceptance Is Better Than Rejection

Other people stand between us and starvation, predation, loneliness, and all the other things that make getting shipwrecked such an unpopular pastime. We depend on others for safety, sustenance, and solidarity, and so we are powerfully motivated to have others like us, accept us, and approve of us (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Leary, 2010). Like the hedonic motive, this motive leaves us vulnerable to social influence.

13.2.2.1 Normative Influence

How are we influenced by other people’s behaviour?

Consider the many things you know about elevators. When you get on an elevator you are supposed to face forward and not talk to the person next to you even if you were talking to that person before you got on the elevator unless you are the only two people on the elevator in which case it is okay to talk and face sideways but still not backward. Although no one ever taught you this rule, you probably picked it up somewhere along the way. The unwritten rules that govern social behaviour are called norms, which are customary standards for behaviour that are widely shared by members of a culture (Cialdini, 2013; Miller & Prentice, 1996). We learn norms with exceptional ease and we obey them with exceptional fidelity because we know that if we do not, others will not approve of us. For example, every human culture has a norm of reciprocity, which is the unwritten rule that people should benefit those who have benefitted them (Gouldner, 1960). When a friend buys you lunch, you return the favour; and if you do not, your friend gets miffed. Indeed, the norm of reciprocity is so strong that when researchers randomly pulled the names of strangers from a telephone directory and sent them all Christmas cards, they received Christmas cards back from most (Kunz & Woolcott, 1976).

Norms are a powerful weapon in the game of social influence. Normative influence occurs when another person’s behaviour provides information about what is appropriate (see FIGURE 13.9). For example, waiters know all about the norm of reciprocity, which is why they often give customers a piece of candy along with the bill. Studies show that customers who receive a candy feel obligated to do “a little extra” for the waiter who did “a little extra” for them (Strohmetz et al., 2002). Indeed, people will sometimes refuse small gifts precisely because they do not want to feel indebted to the gift giver (Shen, Wan, & Wyer, 2011).

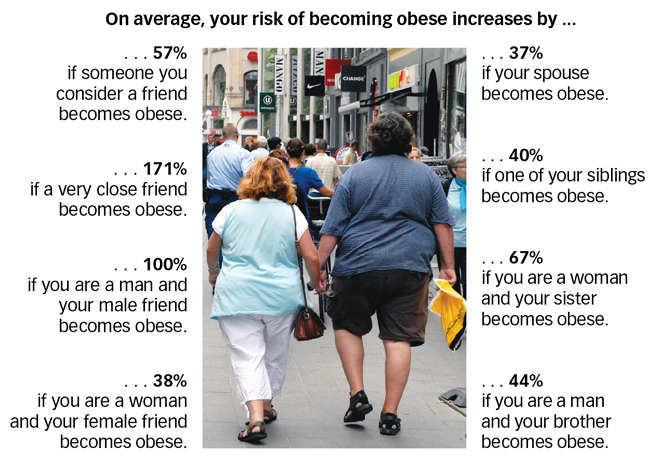

Figure 13.9: The Perils of Connection Other people’s behaviour defines what is “normal,” which is one of the reasons why obesity “spreads” through social networks (Christakis & Fowler, 2007).

Figure 13.9: The Perils of Connection Other people’s behaviour defines what is “normal,” which is one of the reasons why obesity “spreads” through social networks (Christakis & Fowler, 2007).

The norm of reciprocity involves swapping, but the thing being swapped does not have to be a favour. The door-in-the-face technique is an influence strategy that involves getting someone to deny an initial request. Here is how it works: You ask someone for something more valuable than you really want, you wait for that person to refuse (to “slam the door in your face”), and then you ask the person for what you really want. For example, when researchers asked university students to volunteer to supervise adolescents who were going on a field trip, only 17 percent of the students agreed. But when the researchers first asked students to commit to spending 2 hours per week for 2 years working at a youth detention centre (to which every one of the students said no) and then asked them to supervise a field trip, 50 percent of the students agreed (Cialdini et al., 1975). Why? The norm of reciprocity! The researchers began by asking for a large favour, which the student refused. Then the researchers made a concession by asking for a smaller favour. Because the researchers made a concession, the norm of reciprocity demanded that the student make one too—

13.2.2.2 Conformity

Why do we do what we see other people doing?

People can influence us by invoking familiar norms, such as the norm of reciprocity. But if you have ever found yourself sneaking a peek at the diner next to you, hoping to discover whether the little fork is supposed to be used for the shrimp or the salad, then you know that other people can influence us by defining new norms in ambiguous, confusing, or novel situations. Conformity is the tendency to do what others do simply because others are doing it, and it results in part from normative influence.

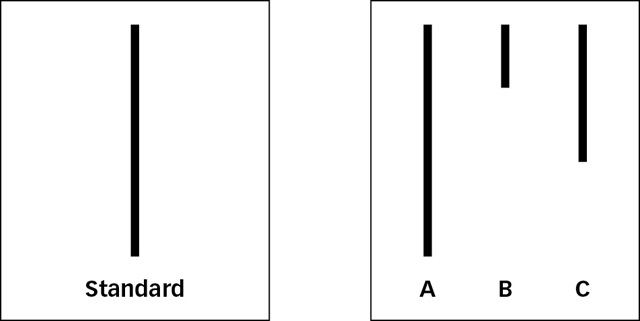

Figure 13.10: Asch’s Conformity Study If you were asked which of the lines on the right (A, B, or C) matches the standard line on the left, what would you say? Research on conformity suggests that your answer would depend, in part, on how other people in the room answered the same question.

Figure 13.10: Asch’s Conformity Study If you were asked which of the lines on the right (A, B, or C) matches the standard line on the left, what would you say? Research on conformity suggests that your answer would depend, in part, on how other people in the room answered the same question.

In a classic study, psychologist Solomon Asch had participants sit in a room with seven other people who appeared to be ordinary participants, but who were actually trained actors (Asch, 1951, 1956). An experimenter explained that the participants would be shown cards with three printed lines and that his or her job was simply to say which of the three lines matched a “standard line” that was printed on another card (see FIGURE 13.10). The experimenter held up a card and then asked each person to answer in turn. The real participant was among the last to be called on. Everything went well on the first two trials, but then on the third trial something really strange happened: the actors all began giving the same wrong answer! What did the real participants do? Seventy-

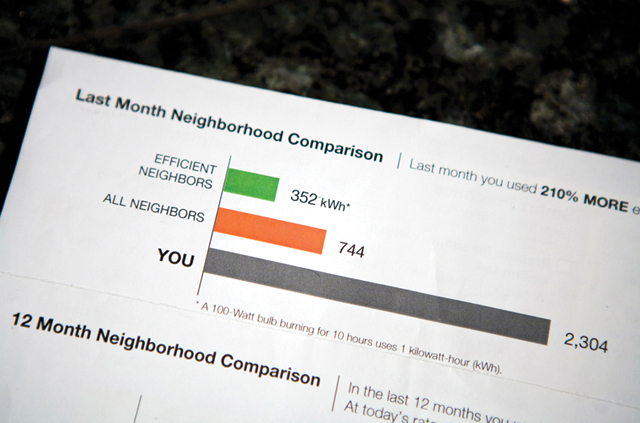

The behaviour of others can tell us what is proper, appropriate, expected, and accepted (in other words, it can define a norm) and once a norm is defined, we feel obliged to honour it. When a Holiday Inn in Tempe, Arizona, left a variety of different “message cards” in guests’ bathrooms in the hopes of convincing those guests to reuse their towels rather than laundering them every day, it discovered that the single most effective message was the one that simply read: “Seventy five percent of our guests use their towels more than once” (Cialdini, 2005). When the electricity provider in Sacramento, California randomly selected 35 000 customers and sent them electric bills showing how their energy consumption compared to that of their neighbours (see FIGURE 13.11), consumption fell by 2 percent (Kaufman, 2009). Clearly, normative influence can be a force for good.

Figure 13.11: Normative Influence at Home In 2008, the Sacramento Municipal Utility District (the electricity provider in Sacramento, California) randomly selected 35 000 of its customers and sent them electric bills like the one shown here. The bill did not just show how much electricity the customer had used; it also showed how much electricity was used by neighbours who lived in similar-

Figure 13.11: Normative Influence at Home In 2008, the Sacramento Municipal Utility District (the electricity provider in Sacramento, California) randomly selected 35 000 of its customers and sent them electric bills like the one shown here. The bill did not just show how much electricity the customer had used; it also showed how much electricity was used by neighbours who lived in similar-13.2.2.3 Obedience

Other people’s behaviour can provide information about norms, but in most situations there are a few people whom we all recognize as having special authority both to define the norms and to enforce them. The guy who works at the movie theatre may be some high school fanboy with a bad haircut and a 10:00 p.m. curfew, but in the context of the theatre, he is the authority. So when he asks you to put away your cell and stop texting in the middle of the movie, you do as you are told. Obedience is the tendency to do what powerful people tell us to do.

OTHER VOICES: 91% of All Students Read This Box and Love It

Binge drinking is a problem on university campuses across North America (Wechsler & Nelson, 2001). About half of all students report doing it, and those who do are much more likely to miss classes, get behind in their school work, drive drunk, and have unprotected sex. So what to do?

Universities have tried a number of remedies—

… Like most universities, Northern Illinois University in DeKalb has a problem with heavy drinking. In the 1980s, the school was trying to cut down on student use of alcohol with the usual strategies. One campaign warned teenagers of the consequences of heavy drinking. “It was the ‘don’t run with a sharp stick you will poke your eye out’ theory of behaviour change,” said Michael Haines, who was the coordinator of the school’s Health Enhancement Services. When that did not work, Haines tried combining the scare approach with information on how to be well: “It’s O.K. to drink if you don’t drink too much—

That one failed, too. In 1989, 45 percent of students surveyed said they drank more than five drinks at parties. This percentage was slightly higher than when the campaigns began. And students thought heavy drinking was even more common; they believed that 69 percent of their peers drank that much at parties.

But by then Haines had something new to try. In 1987 he had attended a conference on alcohol in higher education sponsored by the United States Department of Education. There Wes Perkins, a professor of sociology at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Alan Berkowitz, a psychologist in the school’s counseling centre, presented a paper that they had just published on how student drinking is affected by peers. “There are decades of research on peer influence—

The “aha!” conclusion Perkins and Berkowitz drew was this: maybe students’ drinking behaviour could be changed by just telling them the truth. …

Haines surveyed students at Northern Illinois University and found that they also had a distorted view of how much their peers drink. He decided to try a new campaign, with the theme “most students drink moderately.” The centrepiece of the campaign was a series of ads in the Northern Star, the campus newspaper, with pictures of students and the caption “two thirds of Northern Illinois University students (72%) drink 5 or fewer drinks when they ‘party’.”

Haines’s staff also made posters with campus drinking facts and told students that if they had those posters on the wall when an inspector came around, they would earn $5. (35 percent of the students did have them posted when inspected.) Later they made buttons for students in the fraternity and sorority system—

After the first year of the social norming campaign, the perception of heavy drinking had fallen from 69 to 61 percent. Actual heavy drinking fell from 45 to 38 percent. The campaign went on for a decade, and at the end of it NIU students believed that 33 percent of their fellow students were episodic heavy drinkers, and only 25 percent really were—

Why isn’t this idea more widely used? One reason is that it can be controversial. Telling [university] students “most of you drink moderately” is very different than saying “don’t drink.” (It’s so different, in fact, that the National Social Norms Institute, with headquarters at the University of Virginia, gets its money from Anheuser Busch—

Social norming is a powerful but controversial tool for changing behaviour. When we tell students about drinking on campus, should we tell them what is true (even if that truth is a bit ugly) or should we tell them what is best (even if they are unlikely to do it)?

From the New York Times, March 27, 2013. © 2013 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited. http:/

Why do we do what others tell us to do?

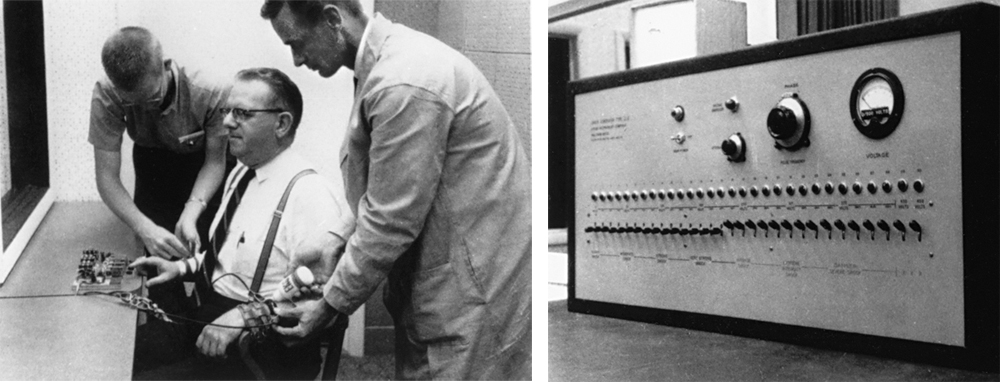

Why do we obey powerful people? Although powerful people are often capable of rewarding and punishing us, research shows that much of their influence is normative (Tyler, 1990). Psychologist Stanley Milgram (1963) demonstrated this in one of psychology’s most infamous experiments. The participants in this experiment met a middle-

Figure 13.12: Milgram’s Obedience Studies The learner (left) is being hooked up to the shock generator (right) that was used in Stanley Milgram’s obedience studies.

Figure 13.12: Milgram’s Obedience Studies The learner (left) is being hooked up to the shock generator (right) that was used in Stanley Milgram’s obedience studies.

After the learner was strapped into his chair, the experiment began. When the learner made his first mistake, the participant dutifully delivered a 15-

Were these people psychopathic sadists? Would normal people electrocute a stranger just because some guy in a lab coat told them to? The answer, it seems, is yes—as long as normal means being sensitive to social norms. The participants in this experiment knew that hurting others is often wrong but not always wrong: Doctors give painful injections, and teachers give painful exams. There are many situations in which it is permissible—

13.2.3 The Accuracy Motive: Right Is Better Than Wrong

When you are hungry, you open the refrigerator and grab an apple because you know that apples (a) taste good and (b) are in the refrigerator. This action, like most actions, relies on both an attitude, which is an enduring positive or negative evaluation of an object or event, and a belief, which is an enduring piece of knowledge about an object or event. In a sense, our attitudes tell us what we should do (eat an apple) and our beliefs tell us how to do it (start by opening the fridge). If our attitudes or beliefs are inaccurate—

13.2.3.1 Informational Influence

How do informational and normative influences differ?

If everyone in the mall suddenly ran screaming for the exit, you would probably join them—

You are the constant target of informational influence. When a salesperson tells you that “most people buy the iPad with extra memory,” she is artfully suggesting that you should take other people’s behaviour as information about the product. Advertisements that refer to soft drinks as “popular” or books as “best sellers” are reminding you that other people are buying these particular drinks and books, which suggests that they know something you do not and that you would be wise to follow their example. Situation comedies provide laugh tracks because the producers know that when you hear other people laughing, you will mindlessly assume that something must be funny (Fein, Goethals, & Kugler, 2007; Nosanchuk & Lightstone, 1974). Bars and nightclubs make people stand in line even when there is plenty of room inside because they know that passersby will see the line and assume that the club is worth waiting for. In short, the world is full of objects and events that we know little about, and we can often cure our ignorance by paying attention to the way in which others are acting toward them. Alas, the very thing that makes us open to information leaves us open to manipulation as well.

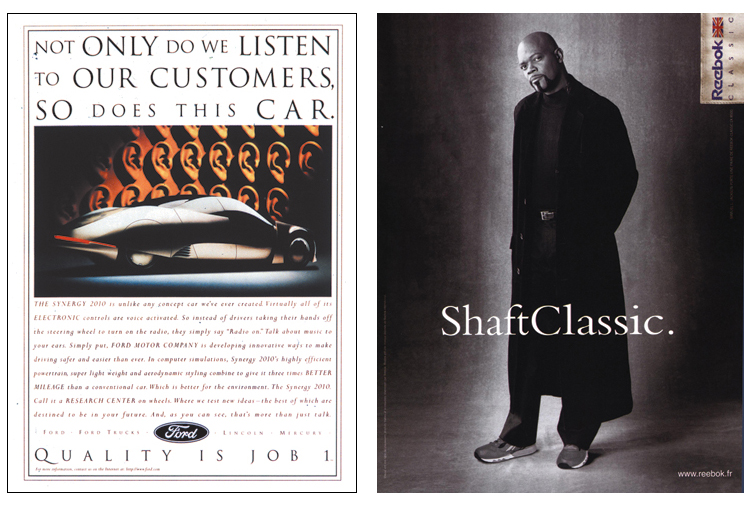

13.2.3.2 Persuasion

When the next federal election rolls around, two things will happen. First, the candidates will say that they intend to win your vote by making arguments that focus on the issues. Second, the candidates will then avoid arguments, ignore issues, and attempt to win your vote with a variety of cheap tricks and emotional appeals. What the candidates promise to do and what they actually do reflect two basic forms of persuasion, which occurs when a person’s attitudes or beliefs are influenced by a communication from another person (Albarracín & Vargas, 2010; Petty & Wegener, 1998). The candidates will promise to persuade you by demonstrating that their positions on the issues are the most practical, intelligent, fair, and beneficial. Having made that promise, they will then devote most of their financial resources to persuading you by other means: for example, by dressing nicely and smiling a lot, by flipping burgers at barbeques and wearing cardigans, by repeatedly “dissing” the other parties’ candidates, and so on. In other words, the candidates will promise to engage in systematic persuasion, which refers to the process by which attitudes or beliefs are changed by appeals to reason, but they will spend most of their time and money engaged in heuristic persuasion, which refers to the process by which attitudes or beliefs are changed by appeals to habit or emotion (Chaiken, 1980; Petty & Cacioppo, 1986).

How do these two forms of persuasion work? Systematic persuasion appeals to logic and reason, and assumes that people will be more persuaded when evidence and arguments are strong rather than weak. Heuristic persuasion appeals to habit and emotion, and assumes that rather than weighing evidence and analyzing arguments, people will often use heuristics (simple shortcuts or “rules of thumb”) to help them decide whether to believe a communication (see the Language and Thought chapter). Which form of persuasion will be more effective depends on whether the person is willing and able to weigh evidence and analyze arguments.

When is it more effective to appeal to reason or to emotion?

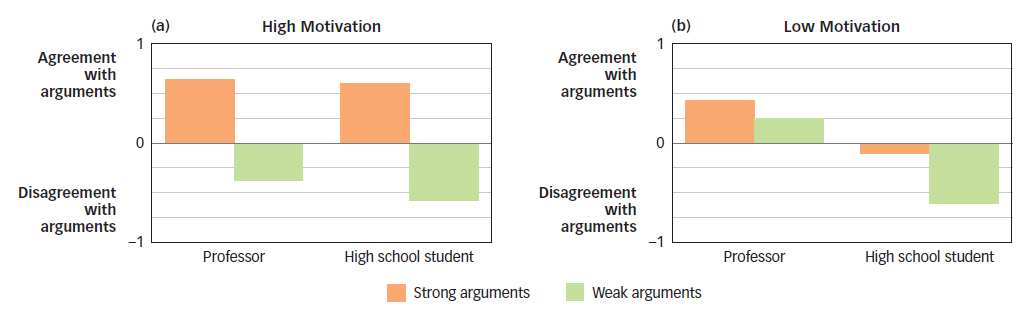

In one study, university students heard a speech that contained either strong or weak arguments in favour of instituting comprehensive exams at their school (Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman, 1981). Some students were told that the speaker was a university professor, and others were told that the speaker was a high school student—

Figure 13.13: Systematic and Heuristic Persuasion (a) Systematic persuasion. When students were motivated to analyze arguments because they would be personally affected by them, their attitudes were influenced by the strength of the arguments (strong arguments were more persuasive than weak arguments), but not by the status of the communicator (the professor was not more persuasive than the high school student). (b) Heuristic persuasion. When students were not motivated to analyze arguments because they would not be personally affected by them, their attitudes were influenced by the status of the communicator (the professor was more persuasive than the high school student), but not by the strength of the arguments (strong arguments were no more persuasive than weak arguments) (Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman, 1981).

Figure 13.13: Systematic and Heuristic Persuasion (a) Systematic persuasion. When students were motivated to analyze arguments because they would be personally affected by them, their attitudes were influenced by the strength of the arguments (strong arguments were more persuasive than weak arguments), but not by the status of the communicator (the professor was not more persuasive than the high school student). (b) Heuristic persuasion. When students were not motivated to analyze arguments because they would not be personally affected by them, their attitudes were influenced by the status of the communicator (the professor was more persuasive than the high school student), but not by the strength of the arguments (strong arguments were no more persuasive than weak arguments) (Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman, 1981).

13.2.3.3 Consistency

Why do we care about being consistent?

If a friend told you that rabbits had just staged a coup in Antarctica and were halting all carrot exports, you probably would not turn on CBC. You would know right away that your friend was joking (or stupid) because the statement is logically inconsistent with other things that you know are true, for example, that rabbits do not foment revolution and that Antarctica does not export carrots. People evaluate the accuracy of new beliefs by assessing their consistency with old beliefs, and although this is not a foolproof method for determining whether something is true, it provides a pretty good approximation. We are motivated to be accurate, and because consistency is a rough measure of accuracy, we are motivated to be consistent as well (Cialdini, Trost, & Newsom, 1995).

That motivation leaves us vulnerable to social influence. For example, the foot-in-the-door technique involves making a small request and then following it with a larger request (Burger, 1999; Freedman & Fraser, 1966). In one study (Pliner et al., 1974), the experimenter went to a Toronto neighbourhood and knocked on doors asking for donations for the Cancer Society. Residents in about one third of the houses in the neighbourhood were simply asked whether they would donate, and 46 percent said they would. The average donation among those who gave money was 58 cents (this was 1974!). The evening before the donation drive, another experimenter canvassed other houses in the neighbourhood, asking residents whether they would be willing to wear a daffodil pin the next day to help publicize the fundraising drive. All residents complied with this request. The next evening, when asked to donate to the Cancer Society, almost twice the proportion of these people (77 percent) said they would, and those people donated an average that was nearly twice as high (92 cents) as in the other group. Why would residents be more likely to grant two requests than one?

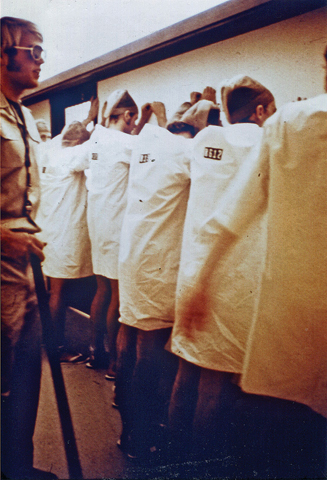

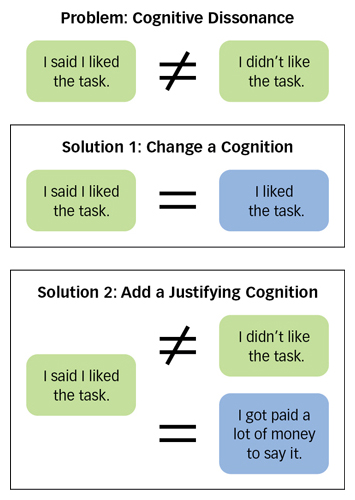

Just imagine how the homeowners in the second group felt. They had already agreed to wear a pin publicizing the Cancer Society funding drive, and yet they knew they did not want to donate much money. As they wrestled with this inconsistency, they probably began to experience a feeling called cognitive dissonance, which is an unpleasant state that arises when a person recognizes the inconsistency of his or her actions, attitudes, or beliefs (Festinger, 1957). When people experience cognitive dissonance they naturally try to alleviate it, and one way to alleviate cognitive dissonance is to restore consistency among one’s actions, attitudes, and beliefs (Aronson, 1969; Cooper & Fazio, 1984). Donating generously to the Cancer Society accomplished that. Recent research shows that this phenomenon can be used to good effect: Hotel guests who were asked at check-

Figure 13.14: Alleviating Cognitive Dissonance Suffering for something of little value can cause cognitive dissonance. One way to alleviate that dissonance is to change your belief about the value of the thing you suffered for.

Figure 13.14: Alleviating Cognitive Dissonance Suffering for something of little value can cause cognitive dissonance. One way to alleviate that dissonance is to change your belief about the value of the thing you suffered for.

What happens when we are inconsistent?

The fact that we can alleviate cognitive dissonance by changing our actions, attitudes, or beliefs has some interesting implications. For instance, in one study, female university students applied to join a weekly discussion on “the psychology of sex.” Women in the control group were allowed to join the discussion, but women in the experimental group were allowed to join the discussion only after first passing an embarrassing test that involved reading pornographic fiction to a strange man. Although the carefully staged discussion was as dull as possible, women in the experimental group found it more interesting than did women in the control group (Aronson & Mills, 1958). Why? Women in the experimental group knew that they had paid a steep price to join the group (“I read all that porn out loud!”), but that belief was inconsistent with the belief that the discussion was worthless. As such, the women experienced cognitive dissonance, which they alleviated by changing their beliefs about the value of the discussion (see the top half of FIGURE 13.14). We normally think that people pay for things because they value them, but as this study shows, people sometimes value things because they have paid for them—

We are motivated to be consistent, but there are inevitably times when we just cannot, for example, when we tell a friend that her new hairstyle is “daring” when it actually resembles a wet skunk after an unfortunate encounter with a snowblower. Why do not we experience cognitive dissonance under such circumstances and come to believe our own lies? Because while telling a friend that her hairstyle is daring is inconsistent with the belief that her hairstyle is hideous, it is perfectly consistent with the belief that one should be nice to one’s friends. When small inconsistencies are justified by large consistencies, cognitive dissonance is reduced.

For example, participants in one study were asked to perform a dull task that involved turning knobs one way, then the other way, and then back again. After the participants were sufficiently bored, the experimenter explained that he desperately needed a few more people to volunteer for the study, and he asked the participants to go into the hallway, find another person, and tell that person that the knob-

People are motivated to experience pleasure and avoid pain (the hedonic motive), and thus can be influenced by rewards and punishments, although these can sometimes backfire.

People are motivated to attain the approval of others (the approval motive), and thus can be influenced by social norms, such as the norm of reciprocity. People often look to the behaviour of others to determine what is normative, and they often end up conforming or obeying, sometimes with disastrous results.

People are motivated to know what is true (the accuracy motive), and thus can be influenced by other people’s behaviours and communications. This motivation also causes them to seek consistency among their attitudes, beliefs, and actions.