14.5 The Psychology of Health: Feeling Good

Two kinds of psychological factors influence personal health: health-

14.5.1 Personality and Health

Different health problems seem to plague different social groups. For example, South Asian Canadians, even those of healthy weight, are more likely to die from a heart attack earlier than the general population, and First Nations people are more susceptible to diabetes than are Asians or Europeans. Beyond these general social categories, personality turns out to be a factor in Canadians’ wellness, with individual differences in optimism and hardiness being important influences (Heart & Stroke Foundation, 2010).

14.5.1.1 Optimism

Pollyanna is one of literature’s most famous optimists. Eleanor H. Porter’s 1913 novel portrayed Pollyanna as a girl who greeted life with boundless good cheer, even when she was orphaned and sent to live with her cruel aunt. Her response to a sunny day was to remark on the good weather, of course, but her response to a gloomy day was to point out how lucky it is that not every day is gloomy! Her crotchety Aunt Polly had exactly the opposite attitude, somehow managing to turn every happy moment into an opportunity for strict correction. A person’s level of optimism or pessimism tends to be fairly stable over time, and research comparing the personalities of twins reared together versus those reared apart suggests that this stability arises because these traits are moderately heritable (Plomin et al., 1992). Perhaps Pollyanna and Aunt Polly were each “born that way.”

An optimist who believes that “in uncertain times, I usually expect the best” is likely to be healthier than a pessimist who believes that “if something can go wrong for me, it will.” One recent review of dozens of studies including tens of thousands of participants concluded that of all of the measures of psychological well-

Who is healthier, the optimist or the pessimist? Why?

Rather than improving physical health directly, optimism seems to aid in the maintenance of psychological health in the face of physical health problems. When sick, optimists are more likely than pessimists to maintain positive emotions, avoid negative emotions such as anxiety and depression, stick to medical regimens their caregivers have prescribed, and keep up their relationships with others. Among women who have surgery for breast cancer, for example, optimists are less likely to experience distress and fatigue after treatment than are pessimists, largely because they keep up social contacts and recreational activities during their treatment (Carver, Lehman, & Antoni, 2003). Optimism also seems to aid in the maintenance of physical health. For instance, optimism appears to be associated with cardiovascular health because optimistic people tend to engage in healthier behaviours like eating a balanced diet and exercising, which in turn leads to a healthier lipid profile (i.e., higher levels of high-

The benefits of optimism raise an important question: If the traits of optimism and pessimism are stable over time—

14.5.1.2 Hardiness

Some people seem to be thick-

Can just anyone develop hardiness? Researchers have attempted to teach hardiness with some success. In one such attempt, participants attended 10 weekly hardiness-

14.5.2 Health-Promoting Behaviours and Self-Regulation

Even without changing our personalities at all, we can do certain things to be healthy. The importance of healthy eating, safe sex, and giving up smoking are common knowledge. But we do not seem to be acting on the basis of this knowledge. Currently 59.9 percent of Canadian men and 45.0 percent of Canadian women are overweight or obese (Statistics Canada, 2013b). The prevalence of unsafe sex is difficult to estimate, but currently in Canada it is estimated that of every 100 sexually active people, 30 will be found to have a sexually transmitted bacterial infection (chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis). This rate is rising quickly (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2010). Another 71 300 people live with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), 25 percent of whom are unaware of their infection, which is usually contracted through unprotected sex with an infected partner (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2012). And despite endless warnings, 16 percent of Canadians still smoke cigarettes (Health Canada, 2013). What is going on?

14.5.2.1 Self-Regulation

Why is it difficult to achieve and maintain self-

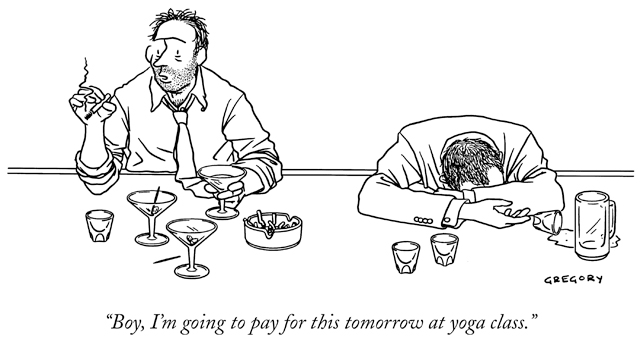

Doing what is good for you is not necessarily easy. Mark Twain once remarked, “The only way to keep your health is to eat what you do not want, drink what you do not like, and do what you would rather not.” Engaging in health-

Self-

Sometimes, though, self-

14.5.2.2 Eating Wisely

In many Western cultures, the weight of the average citizen is increasing at an alarming rate. One explanation is based on our evolutionary history: In order to ensure their survival, our ancestors found it useful to eat well in times of plenty to store calories for leaner times. In postindustrial societies in the twenty-

Short of moving to France, what can you do? Studies indicate that dieting does not always work because the process of conscious self-

Why is exercise a more effective weight-

The restraint problem may be inherent in the very act of self-

14.5.2.3 Avoiding Sexual Risks

People put themselves at risk when they have unprotected vaginal, oral, or anal intercourse. Sexually active adolescents and adults are usually aware of such risks, not to mention the risk of unwanted pregnancy, and yet many behave in risky ways nonetheless. Why does awareness not translate into avoidance? Risk takers harbour an illusion of unique invulnerability, a systematic bias toward believing that they are less likely to fall victim to the problem than are others (Perloff & Fetzer, 1986). For example, a study of sexually active female university students found that respondents judged their own likelihood of getting pregnant in the next year as less than 10 percent, but estimated the average for other women at the university to be 27 percent (Burger & Burns, 1988). Paradoxically, this illusion was even stronger among women in the sample who reported using inadequate or no contraceptive techniques. The tendency to think “It will not happen to me” may be most pronounced when it probably will.

Why does planning ahead reduce sexual risk taking?

Unprotected sex often is the impulsive result of last-

14.5.2.4 Not Smoking

One in two smokers dies prematurely from smoking-

Nicotine, the active ingredient in cigarettes, is addictive, so smoking is difficult to stop once the habit is established (as discussed in the Consciousness chapter). As in other forms of self-

To quit smoking forever, how many times do you need to quit?

Psychological programs and techniques to help people kick the habit include nicotine replacement systems such as gum and skin patches, counselling programs, and hypnosis, but these programs are not always successful. Trying again and again in different ways is apparently the best approach (Schachter, 1982). After all, to quit smoking forever, you only need to quit one more time than you start up. But like the self-

The connection between mind and body can be revealed through the influences of personality and self-

regulation of behaviour on health. The personality traits of optimism and hardiness are associated with reduced risk for illnesses, perhaps because people with these traits can fend off stress.

The self-

regulation of behaviours such as eating, sexuality, and smoking is difficult for many people because self- regulation is easily disrupted by stress; strategies for maintaining self- control can pay off with significant improvements in health and quality of life.

OTHER VOICES: False Hopes and Overwhelming Urges

By Lisa Willemse

Leading research into eating disorders suggests that overcoming obesity is not merely about addressing weight through an improvement in energy balanc—

Much has been studied and written on the physical and dietary contributors to obesity in recent years. As a result, health practitioners are better equipped to make informed recommendations on portion sizes, food choices and exercise regimens. But we now recognize that obesity is a multifaceted issue, and that dietary approaches alone often ignore the powerful behavioural, cognitive and emotional factors in play.

Few researchers understand this concept better than Dr. Janet Polivy. A professor of psychology at the University of Toronto, Dr. Polivy has been unraveling the complicated psychology behind eating and weight disorders for more than 30 years. Her studies have led to some important findings, among them the False Hope Syndrome and the ‘What-

The False Hope Syndrome emerged from a series of studies looking at why diets and weight loss gimmicks do not work for the majority of patients.

“When most of us approach a diet or weight loss program, our expectations tend to be optimistic, particularly about changing things about ourselves, such as our appearance and body weight,” Dr. Polivy explains. “We want to believe the promise diet programs make to us; that it will be fast, easy, effective, and that we will keep the weight off for the long term. But we also want to believe the implicit promises—

Such promises, promoted by books, product packaging and the media, raise expectations falsely and contradict the research evidence, which has conclusively found that weight loss is not easy, fast or permanent.

“There is no magic diet,” says Dr. Polivy. “These unrealistic expectations about changing aspects of oneself contribute to the failure of the effort, and the failure often results in lowered self-

Dr. Polivy identified the ‘What-

The ‘What-

Fighting the urge to toss aside a diet, even for a few hours, is particularly challenging in today’s society, because we are bombarded with food cues. “Everywhere we look it’s all around us, pushing our desires to eat more and reminding us of what we’re missing,” notes Dr. Polivy.

For obese patients who may be struggling with feelings of inadequacy, failure and low self esteem, these temptations can be too hard to overcome and can be followed by feelings of failure and guilt. Greater understanding and communication about these urges can go a long way in helping patients overcome them, she says.

DIET’S MENTAL CHALLENGES

Dr. Janet Polivy’s research has identified many psychological contributors to obesity, among them:

False Hope Syndrome–Dieters place unrealistic expectations about changing aspects of oneself, based on false promises of fast, easy and long-

What-

Adapted with permission from CONDUIT magazine, the official publication of the Canadian Obesity Network (www.obesitynetwork.ca). (c) 2009