15.5 Depressive and Bipolar Disorders: At the Mercy of Emotions

You are probably in a mood right now. Maybe you are happy that it is almost time to get a snack or saddened by something you heard from a friend—

15.5.1 Depressive Disorders

What is the difference between depression and sadness?

Everyone feels sad, pessimistic, and unmotivated from time to time. But for most people these periods are relatively short-

Major depressive disorder (or unipolar depression), which we refer to here simply as “depression,” is characterized by a severely depressed mood and/or inability to experience pleasure that lasts 2 or more weeks and is accompanied by feelings of worthlessness, lethargy, and sleep and appetite disturbance. In a related condition called dysthymia, the same cognitive and bodily problems as in depression are present, but they are less severe and last longer, persisting for at least 2 years. When both types co-

Some people experience recurrent depressive episodes in a seasonal pattern, commonly known as seasonal affective disorder (SAD). In most cases, the episodes begin in fall or winter and remit in spring, and this pattern is due to reduced levels of light over the colder seasons (Westrin & Lam, 2007). Nevertheless, recurrent summer depressive episodes have been reported. A winter-

Approximately 1 in 12 Canadians will experience major depression at some point in their lives (Kessler et al., 2012; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2002a). On average, major depression lasts about 12 weeks (Eaton et al., 2008). However, without treatment, approximately 80 percent of individuals will experience at least one recurrence of the disorder (Judd, 1997; Mueller et al., 1999). Compared with people who have a single episode, individuals with recurrent depression have more severe symptoms, higher rates of depression in their families, more suicide attempts, and higher rates of divorce (Merikangas, Wicki, & Angst, 1994).

Why do more women than men experience depression?

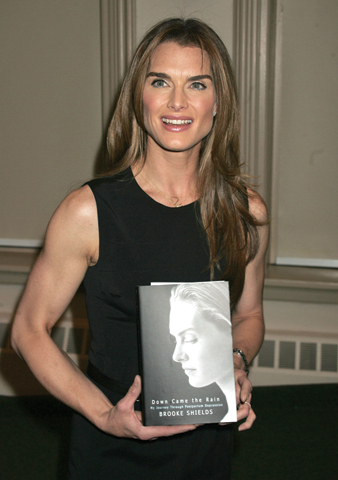

Similar to anxiety disorders, the rate of depression is much higher in women (22 percent) than in men (14 percent) (Kessler et al., 2012). Socioeconomic standing has been invoked as an explanation for women’s heightened risk: Their incomes are lower than those of men, and poverty could cause depression. Sex differences in hormones are another possibility: Estrogen, androgen, and progesterone influence depression; some women experience postpartum depression (depression following childbirth) due to changing hormone balances. It is also possible that the higher rate of depression in women reflects greater willingness by women to face their depression and seek out help, leading to higher rates of diagnosis (Nolen-

15.5.1.1 Biological Factors

Heritability estimates for major depression typically range from 33 to 45 percent (Plomin et al., 1997; Wallace, Schnieder, & McGuffin, 2002). However, like most types of mental disorders, heritability rates vary as a function of severity. For example, a relatively large study of twins found that the concordance rates for severe major depression (defined as three or more episodes) were quite high, with a rate of 59 percent for identical twins and 30 percent for fraternal twins (Bertelsen, Harvald, & Hauge, 1977). In contrast, concordance rates for less severe major depression (defined as fewer than three episodes) fell to 33 percent for identical twins and 14 percent for fraternal twins. Heritability rates for dysthymia are low and inconsistent (Plomin et al., 1997). This makes depression about as heritable as complex medical conditions, like type 2 diabetes and asthma.

Beginning in the 1950s, researchers noticed that drugs that increased levels of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and serotonin could sometimes reduce depression. This observation suggested that depression might be caused by an absolute or relative depletion of these neurotransmitters and sparked a revolution in the pharmacological treatment of depression (Schildkraut, 1965), leading to the development and widespread use of such popular prescription drugs as Prozac and Zoloft, which increase the availability of serotonin in the brain. Further research has shown, however, that reduced levels of these neurotransmitters cannot be the whole story regarding the causes of depression. For example, some studies have found increases in norepinephrine activity among depressed individuals (Thase & Howland, 1995). Moreover, even though the antidepressant medications change neurochemical transmission in less than a day, they typically take at least 2 weeks to relieve depressive symptoms and are not effective in decreasing depressive symptoms in many cases. A biochemical model of depression has yet to be developed that accounts for all the evidence.

Newer biological models of depression have tried to understand depression using a diathesis–

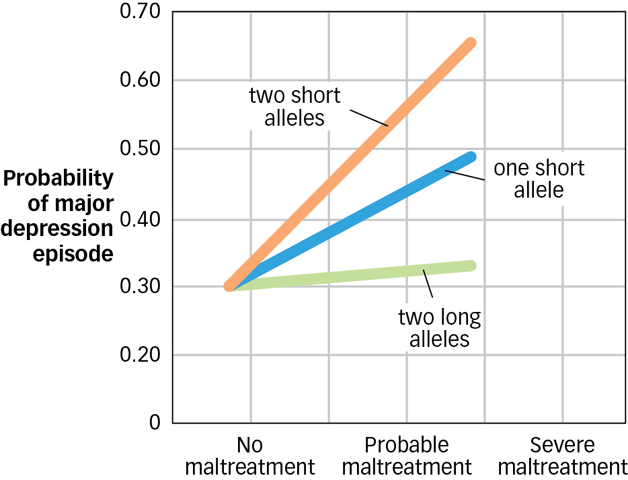

Figure 15.2: Gene × Environment Interactions in Depression Stressful life experiences are much more likely to lead to later depression among those with one short, and especially two short, alleles of the serotonin transporter gene. Those with two long alleles (long alleles are associated with more efficient serotonergic functioning) showed no increased risk of depression, even among those who experienced severe maltreatment.

Figure 15.2: Gene × Environment Interactions in Depression Stressful life experiences are much more likely to lead to later depression among those with one short, and especially two short, alleles of the serotonin transporter gene. Those with two long alleles (long alleles are associated with more efficient serotonergic functioning) showed no increased risk of depression, even among those who experienced severe maltreatment.

Recent research also has begun to tell us what parts of the brain show abnormalities in depression. For instance, some important findings came out of a recent meta-

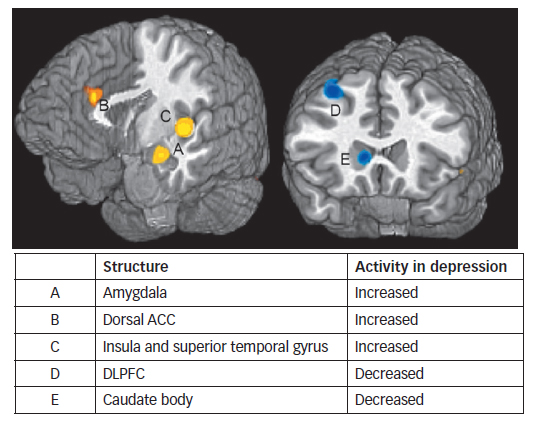

Figure 15.3: Brain and Depression When presented with negative information, people with depression show increased activation in regions of the brain associated with emotional processing such as the amygdala, insula, and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC); and decreased activity in regions associated with cognitive control such as the dorsal striatum and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (Hamilton et al., 2012).

Figure 15.3: Brain and Depression When presented with negative information, people with depression show increased activation in regions of the brain associated with emotional processing such as the amygdala, insula, and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC); and decreased activity in regions associated with cognitive control such as the dorsal striatum and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (Hamilton et al., 2012).

15.5.1.2 Psychological Factors

If optimists see the world through rose-

What is helplessness theory?

Elaborating on this initial idea, researchers proposed a theory of depression that emphasizes the role of people’s negative inferences about the causes of their experiences (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978). Helplessness theory, which is a part of the cognitive model of depression, maintains that individuals who are prone to depression automatically attribute negative experiences to causes that are internal (i.e., their own fault), stable (i.e., unlikely to change), and global (i.e., widespread). For example, a student at risk for depression might view a bad grade on a mathematics test as a sign of low intelligence (internal) that will never change (stable) and that will lead to failure in all his or her future endeavours (global). In contrast, a student without this tendency might have the opposite response, attributing the grade to something external (poor teaching), unstable (a missed study session), and/or specific (boring subject).

The relationship between one’s perceptions and depression has been further developed and supported over the past several decades. The update to Beck’s cognitive model suggests that due to a combination of a genetic vulnerability and negative early life events, people with depression have developed a negative schema (described in the Development chapter). This negative schema is characterized by biases in

interpretations of information (a tendency to interpret neutral information negatively—

seeing the world through grey glass); attention (trouble disengaging from negative information);

memory (better recall of negative information) (Gotlib & Joormann, 2010).

For example, a student at risk for depression who got a bad grade on a test might interpret a well-

15.5.2 Bipolar Disorder

If depression is distressing and painful, would the opposite extreme be better? Not for Virginia Woolf or for Julie, a 20-

Why is bipolar disorder sometimes misdiagnosed as schizophrenia?

In addition to her manic episodes, Julie (like Woolf) had a history of depression. The diagnostic label for this constellation of symptoms is bipolar disorder, a condition characterized by cycles of abnormal, persistent high mood (mania) and low mood (depression). In about two thirds of people with bipolar disorder, manic episodes immediately precede or immediately follow depressive episodes (Whybrow, 1997). The depressive phase of bipolar disorder is often clinically indistinguishable from major depression (Johnson, Cuellar, & Miller, 2009). In the manic phase, which must last at least 1 week to meet DSM requirements, mood can be elevated, expansive, or irritable. Other prominent symptoms include grandiosity, decreased need for sleep, talkativeness, racing thoughts, distractibility, and reckless behaviour (such as compulsive gambling, sexual indiscretions, and unrestrained spending sprees). Psychotic features such as hallucinations (erroneous perceptions) and delusions (erroneous beliefs) may be present, so the disorder can be misdiagnosed as schizophrenia (described in a later section).

Here’s how Kay Redfield Jamison (1995, p. 67) described her own experience with bipolar disorder in An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness.

There is a particular kind of pain, elation, loneliness, and terror involved in this kind of madness. When you are high it is tremendous. The ideas and feelings are fast and frequent like shooting stars, and you follow them until you find better and brighter ones.…But, somewhere, this changes. The fast ideas are far too fast, and there are far too many; overwhelming confusion replaces clarity. Memory goes. Humour and absorption on friends’ faces are replaced by fear and concern. Everything previously moving with the grain is now against—

The lifetime risk for bipolar disorder is about 1 in 40 and does not differ between men and women (Kessler et al., 2012). Bipolar disorder is typically a recurrent condition, with approximately 90 percent of afflicted people suffering from several episodes over a lifetime (Coryell et al., 1995). About 10 percent of people with bipolar disorder have rapid cycling bipolar disorder, characterized by at least four mood episodes (either manic or depressive) every year, and this form of the disorder is particularly difficult to treat (Post et al., 2008). Rapid cycling is more common in women than in men and is sometimes precipitated by taking certain kinds of antidepressant drugs (Liebenluft, 1996; Whybrow, 1997). Unfortunately, bipolar disorder tends to be persistent. In one study, 24 percent of the participants had relapsed within 6 months of recovery from an episode, and 77 percent had at least one new episode within 4 years of recovery (Coryell et al., 1995).

Some have suggested that people with psychotic and mood (especially bipolar) disorders have higher creativity and intellectual ability (Andreasen, 2011). In bipolar disorder, the suggestion goes, before the mania becomes too pronounced, the energy, grandiosity, and ambition that it supplies may help people achieve great things. In addition to Virginia Woolf, notable individuals thought to have had the disorder include Isaac Newton, Vincent van Gogh, Abraham Lincoln, Ernest Hemingway, Winston Churchill, and Theodore Roosevelt.

15.5.2.1 Biological Factors

What findings offer exciting new evidence of why symptoms of different disorders seem to overlap?

Among the various mental disorders, bipolar disorder has one of the highest rates of heritability, with concordance from 40 to 70 percent for identical twins and 10 percent for fraternal twins (Craddock & Jones, 1999). Like most other disorders, it is likely that bipolar disorder is polygenic, arising from the interaction of multiple genes that combine to create the symptoms observed in those with this disorder; however, these have been difficult to identify. Adding to the complexity, there also is evidence of pleiotropic effects, in which one gene influences one’s susceptibility to multiple disorders. For instance, one recent study revealed a shared genetic vulnerability for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. The genes linked to both disorders are associated with compromised abilities both in filtering unnecessary information and recognition memory, as well as problems with dopamine and serotonin transmission—

There is growing evidence that the epigenetic changes you learned about in the Neuroscience and Behaviour chapter can help to explain how it is that genetic risk factors influence the development of bipolar and related disorders. Remember how rat pups whose moms spent less time licking and grooming them experienced epigenetic changes (decreased DNA methylation) that led to a poorer stress response? As you might expect, these same kinds of epigenetic effects seem to help explain who develops symptoms of mental disorders and who does not. For instance, studies examining monozygotic twin pairs (identical twins who share 100 percent of their DNA) in which one develops bipolar disorder or schizophrenia and one does not, reveal significant epigenetic differences between the two, with decreased methylation at genetic locations known to be important in brain development and the occurrence of bipolar disorders and schizophrenia (Dempster et al., 2011; Labrie, Pai, & Petronis, 2012).

15.5.2.2 Psychological Factors

How does stress relate to manic-

Stressful life experiences often precede manic and depressive episodes (Johnson, Cuellar, et al., 2008). One study found that severely stressed individuals took an average of 3 times longer to recover from an episode than did individuals not affected by stress (Johnson & Miller, 1997). The stress–

Mood disorders are mental disorders in which a disturbance in mood is the predominant feature.

Major depression (or unipolar depression) is characterized by a severely depressed mood and/or inability to experience pleasure lasting at least 2 weeks; symptoms include excessive self-

criticism, guilt, difficulty concentrating, sleep and appetite disturbances, lethargy, and possibly suicidal thoughts or attempts at suicide. Dysthymia, a related disorder, involves less severe symptoms that persist for at least 2 years. Bipolar disorder is an unstable emotional condition involving extreme mood swings of depression and mania. The manic phase is characterized by periods of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, lasting at least 1 week.