16.2 Psychological Treatments: Healing the Mind through Interaction

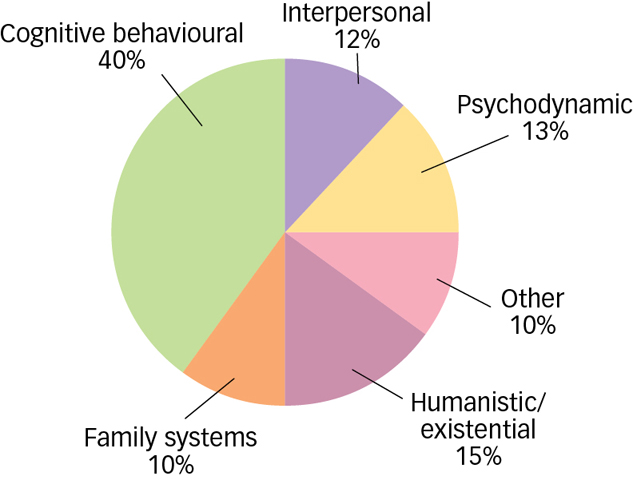

Psychological therapy, or psychotherapy, is an interaction between a socially sanctioned clinician and someone suffering from a psychological problem, with the goal of providing support or relief from the problem. Currently over 500 different forms of psychotherapy exist. Although there are similarities among all the psychotherapies, each approach is unique in its goals, aims, and methods. A survey of 538 psychologists registered with provincial regulatory bodies asked them to describe their theoretical orientation (Hunsley, Ronson, & Cohen, 2013) (see FIGURE 16.1). Many of the practising psychologists endorsed more than one orientation, reflecting the fact that they tended to apply an appropriate theoretical perspective suited to the problem at hand, rather than adhering to a single theoretical perspective for all clients and all types of problems. As Figure 16.1 shows, most of the practitioners relied on five orientations in their work. Cognitive–

Figure 16.1: Dominant therapy orientations of Canadian clinical psychologists in 2009/2010. This chart shows the percentage of practitioners (out of the 538 who returned survey information) who chose each theoretical orientation as one to which they subscribed (Hunsley et al., 2013). The results of a large number of studies conducted over the last 30 years demonstrate the efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy over other forms of therapy for a wide range of mood, anxiety, substance-

Figure 16.1: Dominant therapy orientations of Canadian clinical psychologists in 2009/2010. This chart shows the percentage of practitioners (out of the 538 who returned survey information) who chose each theoretical orientation as one to which they subscribed (Hunsley et al., 2013). The results of a large number of studies conducted over the last 30 years demonstrate the efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy over other forms of therapy for a wide range of mood, anxiety, substance-16.2.1 Psychodynamic Therapy

Psychodynamic psychotherapy has its roots in Freud’s psychoanalytically oriented theory of personality. Psychodynamic psychotherapies explore childhood events and encourage individuals to use this understanding to develop insight into their psychological problems. Psychoanalysis was the first psychodynamic therapy to develop, but it has largely been replaced by modern psychodynamic therapies, such as interpersonal psychotherapy.

16.2.1.1 Psychoanalysis

As you saw in the Personality chapter, psychoanalysis assumes that people are born with aggressive and sexual urges that are repressed during childhood development through the use of defense mechanisms. Psychoanalysts encourage their clients to bring these repressed conflicts into consciousness so that the clients can understand them and reduce their unwanted influences. Psychoanalysts focus a great deal on early childhood events because they believe that urges and conflicts were likely to be repressed during this time.

Traditional psychoanalysis involves four or five sessions per week over an average of 3 to 6 years (Ursano & Silberman, 2003). During a session, the client reclines on a couch, facing away from the analyst, and is asked to express whatever thoughts and feelings come to mind. Occasionally, the therapist may comment on some of the information presented by the client, but does not express his or her values and judgments. The stereotypic image you might have of psychological therapy—

16.2.1.2 What Happens in Psychoanalysis

The goal of psychoanalysis is for the client to understand the unconscious in a process Freud called developing insight. A psychoanalyst can use several key techniques to help the client develop insight, including the following.

16.2.1.2.1 Free Association

In free association, the client reports every thought that enters the mind, without censorship or filtering. This strategy allows the stream of consciousness to flow unimpeded. If the client stops, the therapist prompts further associations (“And what does that make you think of?”). The therapist may then look for themes that recur during therapy sessions.

16.2.1.2.2 Dream Analysis

Psychoanalysis may treat dreams as metaphors that symbolize unconscious conflicts or wishes and that contain disguised clues that the therapist can help the client understand. A psychoanalytic therapy session might begin with an invitation for the client to recount a dream, after which the client might be asked to participate in the interpretation by freely associating to the dream.

16.2.1.2.3 Interpretation

This is the process by which the therapist deciphers the meaning (e.g., unconscious impulses or fantasies) underlying what the client says and does. Interpretation is used throughout therapy, during free association and dream analysis, as well as in other aspects of the treatment. During the process of interpretation, the therapist suggests possible meanings to the client, looking for signs that the correct meaning has been discovered.

16.2.1.2.4 Analysis of Resistance

What might a client’s resistance signal to a psychoanalyst?

In the process of “trying on” different interpretations of the client’s thoughts and actions, the therapist may suggest an interpretation that the client finds particularly unacceptable. Resistance is a reluctance to cooperate with treatment for fear of confronting unpleasant unconscious material. For example, the therapist might suggest that the client’s problem with obsessive health worries could be traced to a childhood rivalry with her mother for her father’s love and attention. The client could find the suggestion insulting and resist the interpretation. The therapist might interpret this resistance as a signal not that the interpretation is wrong but instead that the interpretation is on the right track. If a client always shifts the topic of discussion away from a particular idea, it might signal to the therapist that this is indeed an issue the client could be directed to confront in order to develop insight.

Through the course of meeting so frequently over such a long period of time, the client and psychoanalyst often develop a close relationship. Freud noticed this relationship developing in his analyses and was at first troubled by it: Clients would develop an unusually strong attachment to him, almost as though they were viewing him as a parent or a lover, and he worried that this could interfere with achieving the goal of insight. Over time, however, he came to believe that the development and resolution of this relationship was a key process of psychoanalysis. Transference occurs when the analyst begins to assume a major significance in the client’s life and the client reacts to the analyst based on unconscious childhood fantasies. Successful psychoanalysis involves analyzing the transference so that the client understands this reaction and why it occurs.

16.2.1.3 Beyond Psychoanalysis

In what common ways do modern psychodynamic theories differ from Freudian analysis?

Although Freud’s insights and techniques are fundamental, modern psychodynamic treatments differ from classic psychoanalysis in both their content and procedures. One of the most widely used psychodynamic treatments is interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), a form of psychotherapy that focuses on helping clients improve current relationships (Weissman, Markowitz, & Klerman, 2000). In terms of content, rather than using free association, therapists using IPT talk to clients about their interpersonal behaviours and feelings. They pay particular attention to the client’s grief (an exaggerated reaction to the loss of a loved one), role disputes (conflicts with a significant other), role transitions (changes in life status, such as starting a new job, getting married, or retiring), or interpersonal deficits (lack of the necessary skills to start or maintain a relationship). The treatment focuses on interpersonal functioning with the assumption that, as interpersonal relations improve, symptoms will subside.

Modern psychodynamic psychotherapies such as IPT also differ from classical psychoanalysis in the procedures used. For starters, in modern psychodynamic therapy the therapist and client typically sit face-

Although psychodynamic therapy has been around for a long time and continues to be widely practised, there is relatively little evidence for its effectiveness. Comparisons to other forms of treatment such as cognitive behaviour therapy (described later) suggest that psychodynamic therapy is somewhat less effective (Watzke et al., 2012). Moreover, there is some evidence that some of the aspects of psychodynamic therapy long believed to be effective may actually be harmful. For instance, research suggests that the more a therapist makes interpretations about perceived transference in the client, the worse the therapeutic alliance and the worse the clinical outcome (Henry et al., 1994). Despite findings like these, there is some evidence that long-

16.2.2 Humanistic and Existential Therapies

How does a humanistic view of human nature differ from a psychodynamic view?

Humanistic and existential therapies emerged in the middle of the twentieth century, in part as a reaction to the negative views that psychoanalysis holds about human nature. Humanistic and existential therapies assume that human nature is generally positive, and they emphasize the natural tendency of each individual to strive for personal improvement. Humanistic and existential therapies share the assumption that psychological problems stem from feelings of alienation and loneliness, and that those feelings can be traced to failures to reach one’s potential (in the humanistic approach) or from failures to find meaning in life (in the existential approach). Although interest in these approaches peaked in the 1960s and 1970s, some therapists continue to use these approaches today. Two well-

16.2.2.1 Person-Centred Therapy

Person-centred therapy (or client-centred therapy) assumes that all individuals have a tendency toward growth and that this growth can be facilitated by acceptance and genuine reactions from the therapist. American psychologist Carl Rogers (1902–

Rogers encouraged person-

The goal is not to uncover repressed conflicts, as in psychodynamic therapy, but instead to try to understand the client’s experience and reflect that experience back to the client in a supportive way, encouraging the client’s natural tendency toward growth. This style of therapy is reminiscent of psychoanalysis in its way of encouraging the client toward the free expression of thoughts and feelings.

16.2.2.2 Gestalt Therapy

Gestalt therapy was founded by Frederick “Fritz” Perls (1893–

Gestalt therapy emphasizes the experiences and behaviours that are occurring at that particular moment in the therapy session. For example, if a client is talking about something stressful that occurred during the previous week, the therapist might shift the attention to the client’s current experience by asking, “How do you feel as you describe what happened to you?” This technique is known as focusing. Clients are also encouraged to put their feelings into action. One way to do this is the empty chair technique, in which the client imagines that another person (e.g., a spouse, a parent, a co-

16.2.3 Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies

Unlike the talk therapies described above, behavioural and cognitive treatments emphasize actively changing a person’s current thoughts and behaviours as a way to decrease or eliminate their psychopathology. In the evolution of psychological treatments, clients started out lying down in psychoanalysis, then sitting in psychodynamic and related approaches, but are often standing and engaging in behaviour-

16.2.3.1 Behaviour Therapy

What primary problem did behaviourists have with psychoanalytic ideas?

Whereas Freud developed psychoanalysis as an offshoot of hypnosis and other techniques used by other clinicians before him, behaviour therapy was developed based on laboratory findings from earlier behavioural psychologists. As you read in the Psychology: Evolution of a Science chapter, behaviourists rejected theories that were based on “invisible” mental properties that were difficult to test and impossible to observe directly. Behaviourists found psychoanalytic ideas particularly hard to test: How do you know whether a person has an unconscious conflict or whether insight has occurred? Behavioural principles, in contrast, focused solely on behaviours that could be observed (e.g., avoidance of a feared object, such as refusing to get on an airplane). Behaviour therapy assumes that disordered behaviour is learned and that symptom relief is achieved through changing overt maladaptive behaviours into more constructive behaviours. A variety of behaviour therapy techniques have been developed for many disorders, based on the learning principles you encountered in the Learning chapter, including operant conditioning procedures (which focus on reinforcement and punishment) and classical conditioning procedures (which focus on extinction). Here are three examples of behaviour therapy techniques in action:

16.2.3.1.1 Eliminating Unwanted Behaviours

How would you change a 3-

16.2.3.1.2 Promoting Desired Behaviours

Candy and time-

16.2.3.1.3 Reducing Unwanted Emotional Responses

How might exposure therapy help treat a phobia or fear of a specific object?

One of the most powerful ways to reduce fear is by gradual exposure to the feared object or situation. Exposure therapy involves confronting an emotion-

|

Item |

Fear (0– |

|---|---|

|

1. Have a party and invite everyone from work |

99 |

|

2. Go to a holiday party for 1 hour without drinking |

90 |

|

3. Invite Cindy to have dinner and see a movie |

85 |

|

4. Go for a job interview |

80 |

|

5. Ask boss for a day off work |

65 |

|

6. Ask questions in a meeting at work |

65 |

|

7. Eat lunch with co- |

60 |

|

8. Talk to a stranger on the bus |

50 |

|

9. Talk to cousin on the telephone for 10 minutes |

40 |

|

10. Ask for directions at the gas station |

35 |

|

Source: Ellis (1991). |

|

Exposure therapy can also help people overcome unwanted emotional and behavioural responses through exposure and response prevention. Persons with OCD, for example, might have recurrent thoughts that their hands are dirty and need washing. Washing stops the uncomfortable feelings of contamination only briefly, though, and they wash again and again in search of relief. In exposure with response prevention, they might be asked in therapy to get their hands dirty on purpose (first by touching a coin picked up from the ground, then by touching a public toilet, and later by touching a dead mouse) and leave them dirty for hours. They may need to do this only a few times to break the cycle and be freed from the obsessive ritual (Foa et al., 2007).

16.2.3.2 Cognitive Therapy

Whereas behaviour therapy focuses primarily on changing a person’s behaviour, cognitive therapy, as the name suggests, focuses on helping a client identify and correct any distorted thinking about self, others, or the world (Beck, 2005). For example, behaviourists might explain a phobia as the outcome of a classical conditioning experience such as being bitten by a dog, where the dog bite leads to the development of a dog phobia through the association of the dog with the experience of pain. Cognitive theorists might instead emphasize the interpretation of the event. It might not be the event itself that caused the fear, but rather the individual’s beliefs and assumptions about the event and the feared stimulus. In the case of a dog bite, cognitive theorists might focus on a person’s new or strengthened belief that dogs are dangerous to explain the fear.

How might a client restructure a negative self-

Cognitive therapies use a principal technique called cognitive restructuring, which involves teaching clients to question the automatic beliefs, assumptions, and predictions that often lead to negative emotions and to replace negative thinking with more realistic and positive beliefs. Specifically, clients are taught to examine the evidence for and against a particular belief or to be more accepting of outcomes that may be undesirable yet still manageable. For example, a depressed client may believe that she is stupid and will never pass her university courses—

|

Belief |

Emotional Response |

|---|---|

|

I have to get this done immediately. |

Anxiety, stress |

|

I must be perfect. |

|

|

Something terrible will happen. |

|

|

Everyone is watching me. |

Embarrassment, social anxiety |

|

I will not be able to make friends. |

|

|

People know something is wrong with me. |

|

|

I am a loser and will always be a loser. |

Sadness, depression |

|

Nobody will ever love me. |

|

|

She did that to me on purpose. |

Anger, irritability |

|

He is evil and should be punished. |

|

|

Things ought to be different. |

|

|

Source: Ellis (1991). |

|

Any of these irrational beliefs might bedevil a person with serious emotional problems if left unchallenged and are potential targets for cognitive restructuring. In therapy sessions, the cognitive therapist will help the client to identify evidence that supports, and fails to support, each negative thought in order to help the client generate more balanced thoughts that accurately reflect the true state of affairs. In other words, the clinician tries to remove the dark lens through which the client views the world, not with the goal of replacing it with rose-

|

Clinician: |

Last week I asked you to keep a thought record of situations that made you feel very depressed, at least one per day, and the automatic thoughts that popped into your mind. Were you able to do that? |

|

Client: |

Yes. |

|

Clinician: |

Great. Did you bring it in with you today? |

|

Client: |

Yes, here it is. |

|

Clinician: |

Wonderful, I am glad you were able to complete this assignment. Let’s take a look at this together. What’s the first situation that you recorded? |

|

Client: |

Well…I went out on Friday night with my friends, which I thought would be fun and help me to feel better. But I was feeling kind of down about things and I ended up not really talking to anyone, which led me to just sit in the corner and drink all night, which caused me to get so drunk that I passed out at the party. I woke up the next day feeling embarrassed and more depressed than ever. |

|

Clinician: |

OK, sounds like a tough situation. So the situation is you had too much to drink and passed out. The resulting emotion you had was depression. How intense was your feeling of depression on a scale of 0 to 100? |

|

Client: |

90. |

|

Clinician: |

OK, and what thoughts automatically popped into your head? |

|

Client: |

I can’t control myself. I’ll never be able to control myself. My friends think I’m a loser and will never want to hang out with me again. |

|

Clinician: |

OK, and which of these thoughts led you to feel most depressed? |

|

Client: |

That my friends think I’m a loser and won’t want to hang out with me anymore. |

|

Clinician: |

Alright, so let’s focus on that one for a minute. What evidence can you think of that supports this thought? |

|

Client: |

Well…um…I got really drunk and so they have to think I’m a loser. I mean, who does that? |

|

Clinician: |

OK, write that down on your thought record in this column here. Anything else? Is there any other evidence you can think of that supports those thoughts? |

|

Client: |

No. |

|

Clinician: |

All right. Now let’s take a moment to think about whether there is any evidence that does not support those thoughts. Did anything happen that suggests that your friends don’t think you are a loser or that they do want to keep hanging out with you? |

|

Client: |

Well…apparently some kids were making fun of me when I was passed out and my friends stopped them. And they also brought me home safely and then called the next day and joked about what happened and my one friend Tommy said something like “we’ve all been there” and that he wants to hang out again this weekend. |

|

Clinician: |

OK, great, write that down in this next column. This is very interesting. So on one hand, you feel depressed and have thoughts that you are a loser and your friends do not like you. But on the other hand, you have some pretty real- |

|

Client: |

Yeah, I guess you’re right if you put it that way. I didn’t think about it like that. |

|

Clinician: |

So now if we were going to replace your first thoughts, which don’t seem to have a lot of real- |

|

Client: |

Probably something like, my friends probably weren’t happy about the fact that I got so drunk because then they had to take care of me, but they are my friends and were there for me and want to keep hanging out with me. |

|

Clinician: |

Excellent job. I think that sounds just right based on the evidence, write that down in the next column. And how much do you believe in this new thought on a scale of 0 to 100? |

|

Client: |

I think it is actually pretty accurate, so I would say 95. |

|

Clinician: |

And thinking about this new more balanced thought rather than your first one, how would you rate your depression? |

|

Client: |

Much lower than before. Probably a 40. I’m still not happy that I got so drunk, but less depressed about my friends. |

In addition to cognitive restructuring techniques, which try to change a person’s thoughts to be more balanced or accurate, some forms of cognitive therapy also include techniques for coping with unwanted thoughts and feelings, techniques that resemble meditation (see the Consciousness chapter). Clients may be encouraged to attend to their troubling thoughts or emotions or be given meditative techniques that allow them to gain a new focus (Hofmann & Asmundson, 2008). One such technique, called mindfulness meditation, teaches an individual to be fully present in each moment; to be aware of his or her thoughts, feelings, and sensations; and to detect symptoms before they become a problem. Researchers have found mindfulness meditation to be helpful for preventing relapse in depression. In one study, people recovering from depression were about half as likely to relapse during a 60-

16.2.3.3 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

Why do most therapists use a blend of cognitive and behavioural strategies?

Historically, cognitive and behavioural therapies were considered distinct systems of therapy, and some people continue to follow this distinction, using solely behavioural or cognitive techniques. Today, the extent to which therapists use cognitive versus behavioural techniques depends on the individual therapist as well as the type of problem being treated. Most therapists working with anxiety and depression use a blend of cognitive and behavioural therapeutic strategies, often referred to as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). In a way, this technique acknowledges that there may be behaviours that people cannot control through rational thought, but also that there are ways of helping people think more rationally when thought does play a role. In contrast to traditional behaviour therapy and cognitive therapy, CBT is problem focused, meaning that it is undertaken for specific problems (e.g., reducing the frequency of panic attacks or returning to work after a bout of depression), and action oriented, meaning that the therapist tries to assist the client in selecting specific strategies to help address those problems. The client is expected to do things, such as engage in exposure exercises, practise behaviour change skills or use a diary to monitor relevant symptoms (e.g., the severity of depressed mood, panic attack symptoms). This is in contrast to psychodynamic or other therapies where goals may not be explicitly discussed or agreed on and the client’s only necessary action is to attend the therapy session.

CBT also contrasts with psychodynamic approaches in its assumptions about what the client can know. CBT is transparent in that nothing is withheld from the client. By the end of the course of therapy, most clients have a very good understanding of the treatment they have received as well as the specific techniques that are used to make the desired changes. For example, clients with OCD who fear contamination would feel confident in knowing how to confront feared situations such as public washrooms and why confronting this situation is helpful.

Cognitive behavioural therapies have been found to be effective for a number of disorders (Butler et al., 2006) (see the Hot Science box below). Substantial effects of CBT have been found for unipolar depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, post-

HOT SCIENCE: “Rebooting” Psychological Treatment

Modern psychotherapy has advanced far beyond the days of Freud and his free-

Although most psychologists providing treatment to those with psychological disorders still use traditional psychotherapy, researchers are developing and testing new methods of assessing and treating disorders that make creative use of new technologies. One of the most exciting recent advances in psychological treatment involves computerized training programs. For example, research suggests that biases in the ways that people process information cause psychological disorders. Cognitive bias modification (CBM) is a computerized intervention that focuses on eliminating these biases (MacLeod & Mathews, 2012). Specifically, people with social anxiety show selective attention for threatening information (e.g., when shown several faces they have an automatic tendency to look at the angrier one). In one form of CBM for social anxiety, the patient completes a computerized training program in which he or she is repeatedly shown pairs of faces, one angry and one neutral, that flash on the screen very quickly (for 500 ms) after which the letter “E” or “F” appears behind one of them and the patient’s task is to indicate whether the letter is an “E” or “F.” In CBM, the “E” or “F” always, or nearly always, appears behind the neutral face, which over time teaches the person to ignore the angry face and attend to the neutral face, thus reducing their tendency to attend to threatening faces. The training is intended to generalize beyond faces to reduce attention to threatening stimuli in general. In a recent placebo-

In addition to new forms of treatment that can be administered in clinics, advances in technology are allowing psychologists to bring the clinic into people’s everyday life. Psychologists are now using computers, cellular phones, and wearable bio-

16.2.4 Group Treatments: Healing Multiple Minds at the Same Time

When is group therapy the best option?

It is natural to think of psychopathology as an illness that affects only the individual. A particular person “is depressed,” for example, or “has anxiety.” Yet each person lives in a world of other people, and interactions with others may intensify and even create disorders. A depressed person may be lonely after moving away from friends and loved ones, or an anxious person could be worried about pressures from parents. These ideas suggest that people might be able to recover from disorders in the same way they got into them—

16.2.4.1 Couples and Family Therapy

When a couple is “having problems,” neither individual may be suffering from any psychopathology. Rather, it may be the relationship itself that is disordered. Couples therapy is when a married, co-

There are cases when therapy with even larger groups is warranted. An individual may be having a problem—

In family therapy, the “client” is the entire family. Family therapists believe that problem behaviours exhibited by a particular family member are the result of a dysfunctional family. For example, an adolescent girl suffering from bulimia might be treated in therapy with her mother, father, and older brother. The therapist would work to understand how the family members relate to one another, how the family is organized, and how it changes over time. In discussions with the family, the therapist might discover that the parents’ excessive enthusiasm about her brother’s athletic career led the girl to try to gain their approval by controlling her weight to become “beautiful.” Both couples and family therapy involve more than one person attending therapy together, and the problems and solutions are seen as arising from the interaction of these individuals rather than simply from any one individual.

16.2.4.2 Group Therapy

Taking these ideas one step further, if individuals (or families) can benefit from talking with a psychotherapist, perhaps they can also benefit from talking with other clients who are talking with the therapist. This is group therapy, a technique in which multiple participants (who often do not know one another at the outset) work on their individual problems in a group atmosphere. The therapist in group therapy serves more as a discussion leader than as a personal therapist, conducting the sessions both by talking with individuals and by encouraging them to talk with one another. Group therapy is often used for people who have a common problem, such as substance abuse, but it can also be used for those with differing problems.

What are the pros and cons of a group therapy approach?

Why do people choose group therapy? One advantage is that attending a group with others who have similar problems shows clients that they are not alone in their suffering. In addition, group members model appropriate behaviours for one another and share their insights about how to deal with their problems. Group therapy is often just as effective as individual therapy (e.g., Jonsson & Hougaard, 2008). So, from a societal perspective, group therapy is much more efficient.

Group therapy also has disadvantages. It may be difficult to assemble a group of individuals who have similar needs. This is particularly an issue with CBT, which tends to focus on specific problems such as depression or panic disorder. Group therapy may become a problem if one or more members undermine the treatment of other group members. This can occur if some group members dominate the discussions, threaten other group members, or make others in the group uncomfortable (e.g., attempting to date other members). Finally, clients in group therapy get less attention than they might in individual psychotherapy.

16.2.4.3 Self-Help and Support Groups

What are the pros and cons of self-

An important offshoot of group therapy is the concept of self-

In some cases, though, self-

AA has 185 000 group meetings that occur around the world (Mack, Franklin, & Frances, 2003). Members are encouraged to follow “12 steps” to reach the goal of lifelong abstinence from all drinking, and the steps include believing in a higher power, practising prayer and meditation, and making amends for harm to others. Most members attend group meetings several times per week, and between meetings they receive additional support from their “sponsor.” A few studies examining the effectiveness of AA have been conducted, and it appears that individuals who participate tend to overcome problem drinking with greater success than those who do not participate in AA (Fiorentine, 1999; Morgenstern et al., 1997). However, several tenets of the AA philosophy are not supported by the research. We know that the general AA program is useful, but questions about which parts of this program are most helpful have yet to be studied.

Considered together, the many social approaches to psychotherapy reveal how important interpersonal relationships are for each of us. It may not always be clear how psychotherapy works, whether one approach is better than another, or what particular theory should be used to understand how problems have developed. What is clear, however, is that social interactions between people—

Psychodynamic therapies, including psychoanalysis, emphasize helping clients gain insight into their unconscious conflicts. Traditional psychoanalysis involves 4 to 5 sessions per week of treatment with a client lying on a couch free-

associating, whereas modern psychodynamic therapies involve one session per week with face- to- face interactions in which therapists help clients solve interpersonal problems. Humanistic approaches (e.g., person-

centred therapy) and existential approaches (e.g., gestalt therapy) focus on helping people to develop a sense of personal worth. Behaviour therapy applies learning principles to specific behaviour problems.

Cognitive therapy is focused on helping people to change the way they think about events in their lives, and teaching them to challenge irrational thoughts.

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), which merges cognitive and behavioural approaches, has been shown to be effective for treating a wide range of psychological disorders.

Group therapies target couples, families, or groups of clients brought together for the purpose of working together to solve their problems.

Self-

help and support groups, such as AA, are common in Canada and around the world but are not well studied.