1.2.1 The Path to Freud and Psychoanalytic Theory

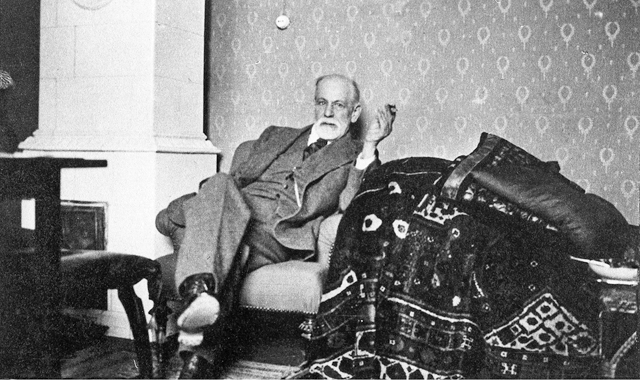

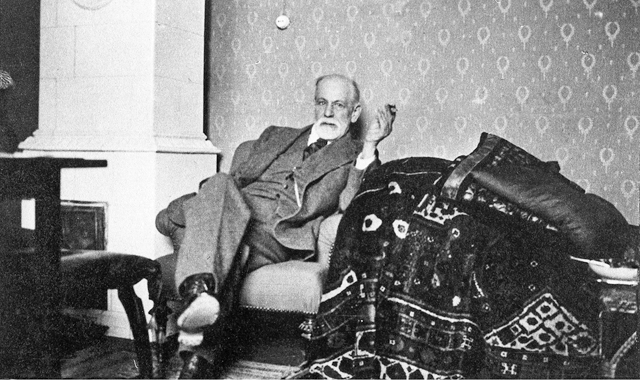

In this photograph, Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) sits by the couch reserved for his psychoanalytic patients, where they would be encouraged to recall past experiences and bring unconscious thoughts into awareness.

RUE DES ARCHIVES/THE GRANGER COLLECTION, NYC — ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

French physicians Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893) and Pierre Janet (1859–1947) reported striking observations when they interviewed patients who had developed a condition known then as hysteria, a temporary loss of cognitive or motor functions, usually as a result of emotionally upsetting experiences. Hysterical patients became blind, paralyzed, or lost their memories, even though there was no known physical cause of their problems. However, when the patients were put into a trancelike state through the use of hypnosis (an altered state of consciousness characterized by suggestibility), their symptoms disappeared: Blind patients could see, paralyzed patients could walk, and forgetful patients could remember. After coming out of the hypnotic trance, the patients forgot what had happened under hypnosis and again showed their symptoms. The patients behaved like two different people in the waking versus hypnotic states.

These peculiar disorders were ignored by Wundt, Titchener, and other laboratory scientists, who did not consider them a proper subject for scientific psychology (Bjork, 1983). But William James believed they had important implications for understanding the nature of the mind (Taylor, 2001). He thought it was important to capitalize on these mental disruptions as a way of understanding the normal operation of the mind. During our ordinary conscious experience we are only aware of a single “me” or “self,” but the aberrations described by Charcot, Janet, and others suggested that the brain can create many conscious selves that are not aware of each other’s existence (James, 1890, p. 400). These striking observations also fuelled the imagination of a young physician from Vienna, Austria, who studied with Charcot in Paris in 1885. His name was Sigmund Freud (1856–1939).

How was Freud influenced by work with hysteric patients?

After his visit to Charcot’s clinic in Paris, Freud returned to Vienna, where he continued his work with hysteric patients. (The word hysteria, by the way, comes from the Latin word hyster [womb]. It was once believed that only women suffered from hysteria, which was thought to be caused by a “wandering womb.”) Working with physician Joseph Breuer (1842–1925), Freud began to make his own observations of hysteric patients and develop theories to explain their strange behaviours and symptoms. Freud theorized that many of the patients’ problems could be traced to the effects of painful childhood experiences that the person could not remember, and he suggested that the powerful influence of these seemingly lost memories revealed the presence of an unconscious mind. According to Freud, the unconscious is the part of the mind that operates outside of conscious awareness but influences conscious thoughts, feelings, and actions. This idea led Freud to develop psychoanalytic theory, an approach that emphasizes the importance of unconscious mental processes in shaping feelings, thoughts, and behaviours. From a psychoanalytic perspective, it is important to uncover a person’s early experiences and to illuminate a person’s unconscious anxieties, conflicts, and desires. Psychoanalytic theory formed the basis for a therapy that Freud called psychoanalysis, which focuses on bringing unconscious material into conscious awareness to better understand psychological disorders. During psychoanalysis, patients recalled past experiences (“When I was a toddler, I was frightened by a masked man on a black horse”) and related their dreams and fantasies (“Sometimes I close my eyes and imagine not having to pay for this session”). Psychoanalysts used Freud’s theoretical approach to interpret what their patients said.

Page 14

In the early 1900s, Freud and a growing number of followers formed a psychoanalytic movement. Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) and Alfred Adler (1870–1937) were prominent in the movement, but both were independent thinkers, and Freud apparently had little tolerance for individuals who challenged his ideas. Soon enough, Freud broke off his relationships with both men so that he could shape the psychoanalytic movement himself (Sulloway, 1992). Psychoanalytic theory became quite controversial (especially in America) because it suggested that understanding a person’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviour required a thorough exploration of the person’s early sexual experiences and unconscious sexual desires. In those days these topics were considered far too racy for scientific discussion.

Most of Freud’s followers, like Freud himself, were trained as physicians and did not conduct psychological experiments in the laboratory (although early in his career, Freud did do some nice laboratory work on the sexual organs of eels). By and large, psychoanalysts did not hold positions in universities and developed their ideas in isolation from the research-based approaches of Wundt, Titchener, James, Hall, Baldwin, and others. One of the few times that Freud met with the leading academic psychologists was at a conference that G. Stanley Hall organized at Clark University in Massachusetts in 1909. It was there that William James and Sigmund Freud met for the first time. Although James worked in an academic setting and Freud worked with clinical patients, both men believed that mental aberrations provide important clues into the nature of mind.

This famous psychology conference, held in 1909 at Clark University, was organized by G. Stanley Hall and brought together many notable figures, such as William James and Sigmund Freud. Both men are circled, with James on the left.

CORBIS

Page 15

1.2.2 Influence of Psychoanalysis and the Humanistic Response

Most historians consider Freud to be one of the most influential thinkers of the twentieth century, and the psychoanalytic movement influenced everything from literature and history to politics and art. Within psychology, psychoanalysis had its greatest impact on clinical practice, but that influence has been considerably diminished over the past 40 years.

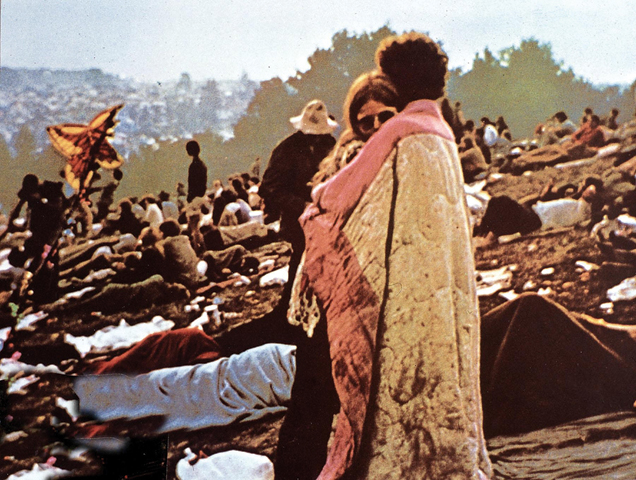

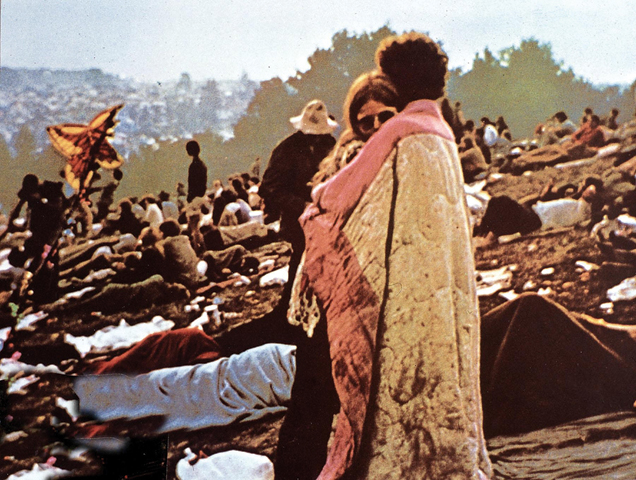

Humanistic psychology offered a positive view of human nature that matched the zeitgeist of the 1960s.

© UNITED ARCHIVES GMBH/ALAMY

This is partly because Freud’s vision of human nature was a dark one, emphasizing limitations and problems rather than possibilities and potentials. He saw people as hostages to their forgotten childhood experiences and primitive sexual impulses, and the inherent pessimism of his perspective frustrated those psychologists who had a more optimistic view of human nature. In America, the years after World War II were positive, invigorating, and upbeat: Poverty and disease were being conquered by technology, the standard of living of ordinary Americans was rising sharply, and people were landing on the moon. The era was characterized by the accomplishments—not the foibles—of the human mind, and Freud’s viewpoint was out of step with the spirit of the times.

Why are Freud’s ideas less influential today?

Freud’s ideas were also difficult to test, and a theory that cannot be tested is of limited use in psychology or other sciences. Although Freud’s emphasis on unconscious processes has had an enduring impact on psychology, psychologists began to have serious misgivings about many aspects of Freud’s theory.

It was in these times that psychologists such as Abraham Maslow (1908–1970) and Carl Rogers (1902–1987) pioneered a new movement called humanistic psychology, an approach to understanding human nature that emphasizes the positive potential of human beings. Humanistic psychologists focused on the highest aspirations that people had for themselves. Rather than viewing people as prisoners of events in their remote pasts, humanistic psychologists viewed people as free agents who have an inherent need to develop, grow, and attain their full potential. This movement reached its peak in the 1960s when a generation of “flower children” found it easy to see psychological life as a kind of blossoming of the spirit. Humanistic therapists sought to help people realize their full potential; in fact, they called them clients rather than patients. In this relationship, the therapist and the client (unlike the psychoanalyst and the patient) were on equal footing. The development of the humanistic perspective was one more reason why Freud’s ideas eventually became less influential.

Psychologists have often focused on patients with psychological disorders as a way of understanding human behaviour. Clinicians such as Jean-Martin Charcot and Pierre Janet studied unusual cases in which patients acted like different people while under hypnosis, raising the possibility that each of us has more than one self.

Through his work with hysteric patients, Sigmund Freud developed psychoanalysis, which emphasized the importance of unconscious influences and childhood experiences in shaping thoughts, feelings, and behaviour.

Happily, humanistic psychologists offered a more optimistic view of the human condition, suggesting that people are inherently disposed toward growth and can usually reach their full potential with a little help from their friends.

Page 16