1.5 Beyond the Individual: Social and Cultural Perspectives

The picture we have painted so far may vaguely suggest a scene from some 1950s science-

1.5.1 The Development of Social Psychology

Social psychology is the study of the causes and consequences of sociality. As this definition suggests, social psychologists address a remarkable variety of topics. Historians trace the birth of social psychology to an experiment conducted in 1895 by psychologist and bicycle enthusiast Norman Triplett, who noticed that cyclists seemed to ride faster when they rode with others. Intrigued by this observation, he conducted an experiment that showed that children reeled in a fishing line faster when tested in the presence of other children than when tested alone. Triplett was not trying to improve the fishing abilities of children, of course, but rather was trying to show that the mere presence of other people can influence performance on even the most mundane kinds of tasks.

How did historical events influence the development of social psychology?

Social psychology’s development began in earnest in the 1930s and was driven by several historical events. The rise of Nazism led many of Germany’s most talented scientists to immigrate to America, and among them were psychologists such as Solomon Asch (1907–

Other historical events also shaped social psychology in its early years. For example, the Holocaust brought the problems of conformity and obedience into sharp focus, leading psychologists such as Asch (1956) and others to examine the conditions under which people can influence each other to think and act in inhuman or irrational ways. The civil rights movement and the rising tensions between African Americans and white Americans led psychologists such as Gordon Allport (1897–

1.5.2 The Emergence of Cultural Psychology

North Americans and Western Europeans are sometimes surprised to realize that most of the people on the planet are members of neither culture. Although we are all more alike than we are different, there is nonetheless considerable diversity within the human species in social practices, customs, and ways of living. Culture refers to the values, traditions, and beliefs that are shared by a particular group of people. Although we usually think of culture in terms of nationality and ethnic groups, cultures can also be defined by age (youth culture), sexual orientation (gay culture), religion (Jewish culture), or occupation (academic culture). Cultural psychology is the study of how cultures reflect and shape the psychological processes of their members (Shweder & Sullivan, 1993). Cultural psychologists study a wide range of phenomena, ranging from visual perception to social interaction, as they seek to understand which of these phenomena are universal and which vary from place to place and time to time.

Perhaps surprisingly, one of the first psychologists to pay attention to the influence of culture was someone recognized today for pioneering the development of experimental psychology, Wilhelm Wundt. He believed that a complete psychology would have to combine a laboratory approach with a broader cultural perspective (Wundt, 1900–

How did anthropologists influence psychology in the 1980s?

Yet, at the time, most anthropologists paid as little attention to psychology as psychologists did to anthropology. Cultural psychology only began to emerge as a strong force in psychology during the 1980s and 1990s, when psychologists and anthropologists began to communicate with each other about their ideas and methods (Stigler, Shweder, & Herdt, 1990). It was then that psychologists rediscovered Wundt as an intellectual ancestor of this area of the field (Jahoda, 1993).

Physicists assume that E = mc2 whether the m is located in Moosejaw, Moscow, or the Orion Nebula. Chemists assume that water is made of hydrogen and oxygen, and that it was made of hydrogen and oxygen in 1609 as well. The laws of physics and chemistry are assumed to be universal, and for much of psychology’s history, the same assumption was made about the principles that govern human behaviour (Shweder, 1991). Absolutism holds that culture makes little or no difference for most psychological phenomena, that “honesty is honesty and depression is depression, no matter where one observes it” (Segall, Lonner, & Berry, 1998, p. 1103). And yet, as any world traveller knows, cultures differ in exciting, delicious, and frightening ways, and things that are true of people in one culture are not necessarily true of people in another. John Berry (of Queen’s University) and his colleagues maintain that relativism holds that psychological phenomena are likely to vary considerably across cultures and should be viewed only in the context of a specific culture (Berry et al., 1992). Although depression is observed in nearly every culture, the symptoms associated with it vary dramatically from one place to another. For example, in Western cultures there is greater emphasis on cognitive symptoms such as worthlessness, whereas in Eastern cultures there is greater focus on somatic symptoms such as fatigue and body aches (Draguns & Tanaka-

Why are psychological conclusions so often relative to the person, place, or culture described?

Today, most cultural psychologists fall somewhere between these two extremes. Most psychological phenomena can be influenced by culture, some are completely determined by it, and others seem to be entirely unaffected. For example, the age of a person’s earliest memory differs dramatically across cultures (MacDonald, Uesiliana, & Hayne, 2000), whereas judgments of facial attractiveness do not (Cunningham et al., 1995). As noted when we discussed evolutionary psychology, it seems likely that the most universal phenomena are those that are closely associated with the basic biology that all human beings share. Conversely, the least universal phenomena are those rooted in the varied socialization practices that different cultures evolve. Of course, the only way to determine whether a phenomenon is variable or constant across cultures is to design research to investigate these possibilities, and cultural psychologists do just that (Cole, 1996; Segall et al., 1998). We will highlight the work of cultural psychologists throughout the text and in Culture & Community boxes like the one in this section concerning cultural differences in analytic and holistic styles of processing information.

CULTURE & COMMUNITY: Analytic and Holistic Styles in Western and Eastern Cultures

The study of cultural influences on mind and behaviour has increased dramatically over the past decade. An especially intriguing line of research has revealed differences in how the world is viewed by people from Western cultures such as North America and Europe, and Eastern cultures such as China, Japan, Korea, and other Asian countries. One of the most consistently observed differences is that people from Western cultures tend to adopt an analytic style of processing information, focusing on an object or person without paying much attention to the surrounding context, whereas people from Eastern cultures tend to adopt a holistic style that emphasizes the relationship between an object or person and the surrounding context (Nisbett & Miyamoto, 2005).

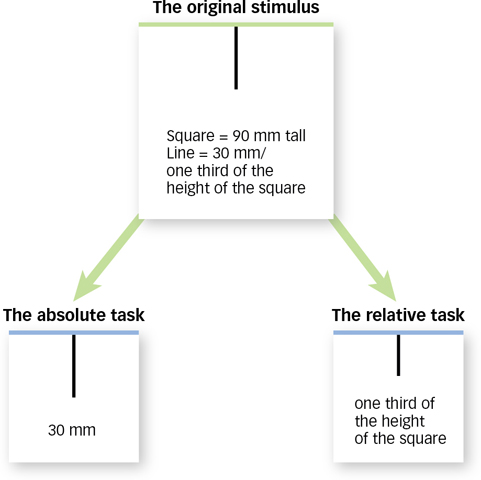

This difference is illustrated nicely by a study in which American and Japanese participants performed a novel task, called the framed-

Social psychology recognizes that people exist as part of a network of other people and examines how individuals influence and interact with one another. Social psychology was pioneered by German émigrés, such as Kurt Lewin, who were motivated by a desire to address social issues and problems.

Cultural psychology is concerned with the effects of the broader culture on individuals and with similarities and differences among people in different cultures. Within this perspective, absolutists hold that culture has little impact on most psychological phenomena, whereas relativists believe that culture has a powerful effect.

Together, social and cultural psychology help expand the discipline’s horizons beyond just an examination of individuals. These areas of psychology examine behaviour within the broader context of human interaction.