1.6 The Profession of Psychology: Past and Present

If ever you find yourself on an airplane with an annoying seatmate who refuses to let you read your magazine, there are two things you can do. First, you can turn to the person and say in a calm and friendly voice, “Did you know that I am covered with strange and angry bacteria?” If that seems a bit extreme, you might instead try saying, “Did you know that I am a psychologist, and I am forming an evaluation of you as you speak?” as this will usually eliminate the problem without getting you arrested. The truth is that most people do not really know what psychology is or what psychologists do, but they do have some vague sense that it is not wise to talk to one. Now that you have been briefly acquainted with psychology’s past, let us consider its present by looking at psychology as a profession. We will look first at the origins of psychology’s professional organizations, next at the contexts in which psychologists tend to work, and finally at the kinds of training required to become a psychologist.

1.6.1 Psychologists Band Together: Psychological Associations

You will recall that when we last saw William James, he was wandering around the greater Boston area, expounding the virtues of the new science of psychology. In July 1892, James and five other psychologists travelled to Clark University to attend a meeting called by G. Stanley Hall. Each worked at a large university where they taught psychology courses, performed research, and wrote textbooks. Although they were too few to make up a jury or even a respectable hockey team, these seven men decided that it was time to form an organization that represented psychology as a profession, and on that day the American Psychological Association (APA) was born. The seven psychologists could scarcely have imagined that today their little club would grow to have more than 150 000 members from all over the world. Although all of the original members were employed by universities or colleges, today academic psychologists make up only 20 percent of the membership, whereas nearly 70 percent of the members work in clinical and health-

1.6.1.1 The Growing Role of Women and Minorities

How has the face of psychology changed as the field has evolved?

In 1892, the APA had 31 members, all of whom were white and all of whom were male. Today, about half of all CPA and APA members are women, and the percentage of non-

1.6.1.2 Psychology in Canada

The development of psychology in Canada paralleled that in Europe and in the United States. As you read earlier, the first psychology laboratory in Canada was established by James Mark Baldwin, a student of Wundt’s, in 1889, at the University of Toronto. Although Baldwin did not stay in Toronto, his laboratory was expanded by August Kirschmann, another student of Wundt’s, around the turn of the twentieth century. Although at most other universities psychology was considered a field of philosophy, by 1926, psychology was established enough at the University of Toronto to became an independent department. McGill University also had an independent psychology department from 1922. Elsewhere, after 1940, independent psychology departments began springing up at Canadian universities.

One of the first graduate students in the new Department of Psychology at McGill University was Donald Olding Hebb (1904–

Brenda Milner, a Cambridge-

1.6.2 What Psychologists Do: Research Careers

Before describing what psychologists do, it should be noted that most people who major in psychology do not go on to become psychologists. Psychology has become a major academic, scientific, and professional discipline with links to many other disciplines and career paths (see the Hot Science box below). That being said, what should you do if you do want to become a psychologist, and what should you fail to do if you desperately want to avoid it? You can become a “psychologist” by a variety of routes, and the people who call themselves psychologists may hold a variety of different degrees. Typically, students finish university and enter graduate school in order to obtain a Ph.D. in some particular area of psychology (e.g., social, cognitive, developmental). During graduate school, students generally gain exposure to the field by taking classes and learn to conduct research by collaborating with their professors. Although William James was able to master every area of psychology because the areas were so small during his lifetime, today a student can spend the better part of a decade mastering just one.

After receiving a Ph.D., you can go on for more specialized research training by pursuing a postdoctoral fellowship under the supervision of an established researcher in his or her area, or apply for a faculty position at a college or university or a research position in government or industry. Academic careers usually involve a combination of teaching and research, whereas careers in government or industry are typically dedicated to research alone.

1.6.2.1 The Variety of Career Paths

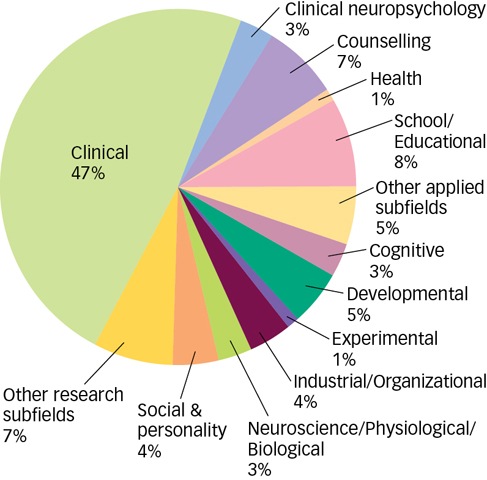

Figure 1.3: The Major Subfields in Psychology Psychologists are drawn to many different subfields in psychology. Here are the percentages of people receiving Ph.D.s in various subfields. Clinical psychology makes up almost half of the doctorates awarded in psychology.

Figure 1.3: The Major Subfields in Psychology Psychologists are drawn to many different subfields in psychology. Here are the percentages of people receiving Ph.D.s in various subfields. Clinical psychology makes up almost half of the doctorates awarded in psychology.Note: The numbers do not add up to 100% due to rounding.

In what ways does psychology contribute to society?

As you saw earlier, research is not the only career option for a psychologist. Most people who call themselves psychologists neither teach nor do research but, rather, they assess or treat people with psychological problems. Most of these clinical psychologists work in private practice, often in partnerships with other psychologists or with psychiatrists (who have earned an M.D., or medical degree, and are allowed to prescribe medication). Other clinical psychologists work in hospitals or medical schools, some have faculty positions at universities or colleges, and some combine private practice with an academic job. Many clinical psychologists focus on specific problems or disorders, such as depression or anxiety, whereas others focus on specific populations such as children, ethnic minority groups, or older adults (see FIGURE 1.3). Counselling psychologists assist people in dealing with work or career issues and changes or help people deal with common crises such as divorce, the loss of a job, or the death of a loved one. Counselling psychologists may have a Ph.D. or an M.A. (master’s degree) in counselling psychology or an M.S.W. (Master of Social Work).

Psychologists are also quite active in educational settings. School psychologists, offer guidance to students, parents, and teachers. A similar proportion of APA members focus on issues in the workplace. Psychologists who work in business or industry are known as industrial/organizational psychologists. They may be involved in assessing potential employees, finding ways to improve productivity, or helping staff and management to develop effective planning strategies for coping with change or anticipated future developments. Of course, this brief list does not begin to cover all the different career paths that someone with training in psychology might take. For instance, sports psychologists help athletes improve their performance, forensic psychologists assist lawyers and courts, and consumer psychologists help companies develop and advertise new products. Indeed, we cannot think of any major enterprise that does not employ psychologists.

HOT SCIENCE: Psychology as a Hub Science

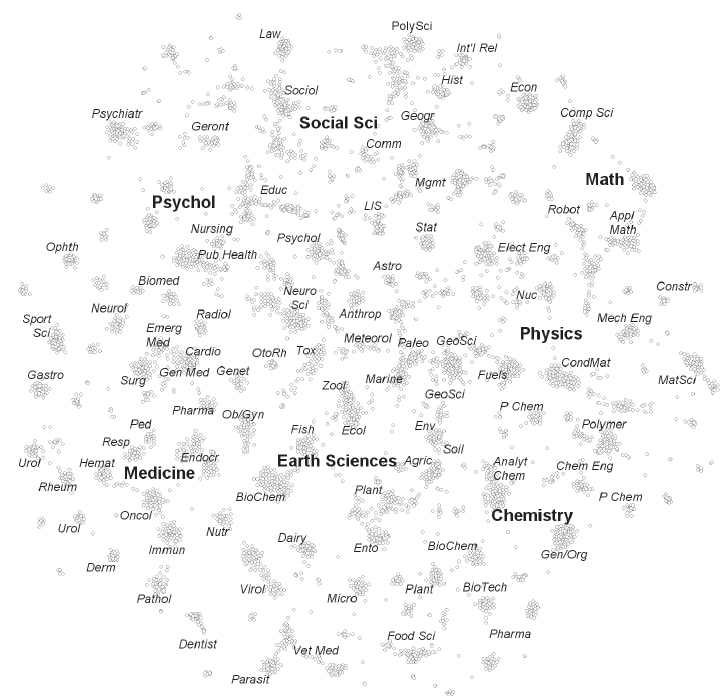

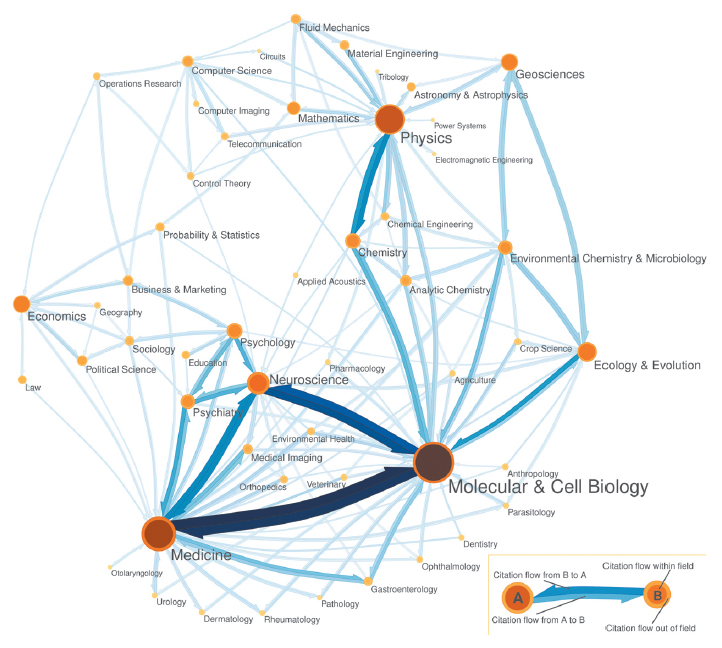

This chapter describes how psychology emerged as a field of study, and the Other Voices box seen earlier illustrates some of the ways in which psychology is indeed a scientific field of study. But where does psychology stand in relation to other areas of science? That is, how big a field is it? What links does it have to other scientific disciplines? What fields (if any) are influenced by psychological science? With recent advances in computing and electronic record keeping, researchers are now able to answer these questions by literally creating maps of science. Information about scientific articles, the journals in which they are published, and the frequency and patterns with which articles in one field are cited by articles in another field, is now fully electronic and available online (in the Science Citation and Social Science Citation Indexes). Researchers can use this information to learn about the interconnectedness of different scientific disciplines.

As an example, in an article called “Mapping the Backbone of Science,” Kevin Boyack and his colleagues (2005) used data from more than 1 million articles, with over 23 million references, published in more than 7000 journals to create a map showing the similarities and interconnectedness of different areas of science based on how frequently journal articles from different disciplines cite each other. The results are fascinating. As shown in the figure on the left, seven major fields, or “hub sciences,” that link with and influence smaller subfields emerged in the data: math, physics, chemistry, earth sciences, medicine, psychology, and social science. The organization of the hubs is interesting to note. As you can see in the figure on the left, psychology sits between medicine and social studies, whereas physics sits between mathematics and chemistry. The location of subfields also matches with what you might expect: public health and neurology fall between psychology and medicine, statistics between psychology and math, and economics between social science and math.

Studies like this one provide an informative picture of how different areas of science relate to each other historically (i.e., the citations in that study dated back many years). But science is dynamic and constantly changing and so an important question is: What does the science look like right now (while you are in school and deciding which classes to take and what career path to follow)? In another study, data from more than 6 million citations, found in over 6000 journals was used to create a map of citation patterns focusing only on citations to articles published in a recent 5-

Studies like these are useful to university administrators, funding agencies, and also to students to help them understand the relationships between different academic departments and how the scientific work of one field relates to the scientific field more broadly. They also show the reach of psychology to other disciplines and support the idea that knowledge about psychology has relevance for many related disciplines and career paths. Good thing you are taking this class!

Even this brief and incomplete survey provides a sense of the wide variety of contexts in which psychologists operate. You can think of psychology as an international community of professionals devoted to advancing scientific knowledge; assisting people with psychological problems and disorders; and trying to enhance the quality of life in work, school, and other everyday settings.

The American Psychological Association (APA) has grown dramatically since it was formed in 1892 and now includes over 150 000 members working in clinical, academic, and applied settings. Psychologists are also represented by professional organizations such as the Association for Psychological Science (APS), which focuses on scientific psychology, and in Canada by the Canadian Psychological Association (CPA), the Canadian Society for Brain Behaviour and Cognitive Sciences (CSBBCS), and the Canadian Association for Neuroscience–

association canadienne de neuroscience (CAN- ACN). Psychology in Canada developed similarly to psychology elsewhere. By the 1920s, the University of Toronto and McGill University had stand-

alone departments of psychology and, by the 1940s, these were beginning to appear at other Canadian universities. Psychologists prepare for research careers through graduate and postdoctoral training, and work in a variety of applied settings, including schools, clinics, and industry.