2.1 Empiricism: How to Know Stuff

When ancient Greeks sprained their ankles, caught the flu, or accidentally set their togas on fire, they had to choose between two kinds of doctors: dogmatists (from dogmatikos, meaning “belief”), who thought that the best way to understand illness was to develop theories about the body’s functions, and empiricists (from empeirikos, meaning “experience”), who thought that the best way to understand illness was to observe sick people. The rivalry between these two schools of medicine did not last long because the people who went to see dogmatists tended to die, which was bad for business. Today we use the word dogmatism to describe the tendency for people to cling to their assumptions, and the word empiricism to describe the belief that accurate knowledge can be acquired through observation. The fact that we can answer questions about the natural world by examining it may seem painfully obvious to you, but this painfully obvious fact has only recently gained wide acceptance. For most of human history, people trusted authority to answer important questions, and it is only in the last millennium (and especially in the past three centuries) that people have begun to trust their eyes and ears more than their elders.

2.1.1 The Scientific Method

What is the scientific method?

Empiricism is the essential element of the scientific method, which is a procedure for finding truth by using empirical evidence. In essence, the scientific method suggests that when we have an idea about the world—

When scientists set out to develop a theory, they generally follow the rule of parsimony, which says that the simplest theory that explains all the evidence is the best one. Parsimony comes from the Latin word parcere, meaning “to spare,” and the rule is often credited to the fourteenth-

We want our theories to be as simple as possible, but we also want them to be right. How do we decide if a theory is right? Theories make specific predictions about what we should observe in the world. For example, if bats really do navigate by making sounds and then listening for echoes, then we should observe that deaf bats cannot navigate. That “should statement” is technically known as a hypothesis, which is a falsifiable prediction made by a theory. The word falsifiable is a critical part of that definition. Some theories, such as “God created the universe,” simply do not specify what we should observe if they are true, and thus no observation can ever falsify them. Because these theories do not give rise to hypotheses, they can never be the subject of scientific investigation. That does not mean they are wrong—

Why can theories be proven wrong but not right?

So what happens when we test a hypothesis? Albert Einstein is reputed to have said that, “No amount of experimentation can ever prove me right, but a single experiment can prove me wrong.” Why should that be? Well, just imagine what you could possibly learn about the navigation-

We cannot observe every bat that has ever been and will ever be, which means that even if the theory was not disproved by your observation there always remains some chance that it will be disproved by some other observation. When evidence is consistent with a theory, it increases our confidence in it, but it never makes us completely certain. The next time you see a newspaper headline that says “Scientists prove theory X correct,” you are hereby authorized to roll your eyes.

The scientific method suggests that the best way to learn the truth about the world is to develop theories, derive hypotheses from them, test those hypotheses by gathering evidence, and then use that evidence to modify the theories. But what exactly does gathering evidence entail?

2.1.2 The Art of Looking

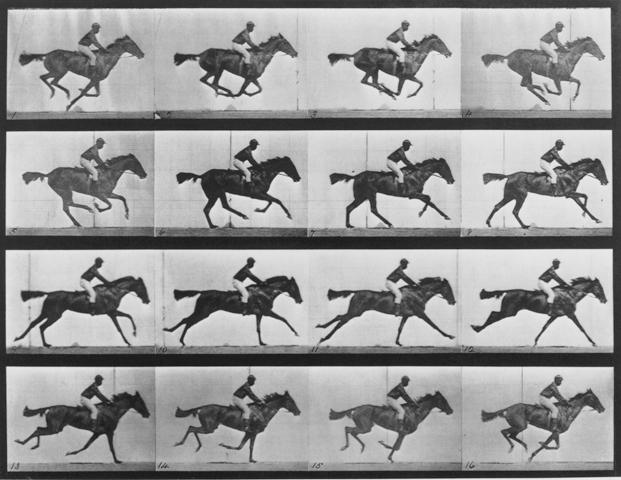

For centuries, people rode horses. And for centuries when they got off their horses they sat around and argued about whether all four of a horse’s feet ever leave the ground at the same time. Some said yes, some said no, and some said they really wished they could talk about something else for a change. In 1877, Eadweard Muybridge invented a technique for taking photographs in rapid succession, and his photographs showed that when horses gallop, all four feet do indeed leave the ground. And that was that. Never again did two riders have the pleasure of a flying horse debate because Muybridge had settled the matter, once and for all time.

But why did it take so long? After all, people had been watching horses gallop for quite a few years, so why did some say that they clearly saw the horse going airborne while others said that they clearly saw at least one hoof on the ground at all times? Because as wonderful as eyes may be, there are a lot of things they cannot see and a lot of things they see incorrectly. We cannot see germs but they are very real. Earth looks perfectly flat but it is imperfectly round. As Muybridge knew, we have to do more than just look if we want to know the truth about the world. Empiricism is the right approach, but to do it properly requires an empirical method, a set of rules and techniques for observation.

In many sciences, the word method refers primarily to technologies that enhance the powers of the senses. Biologists use microscopes and astronomers use telescopes because the things they want to observe are invisible to the naked eye. Human behaviour, on the other hand, is quite visible, so you might expect psychology’s methods to be relatively simple. In fact, the empirical challenges facing psychologists are among the most daunting in all of modern science, thus psychology’s empirical methods are among the most sophisticated in all of modern science. These empirical challenges arise because people have three qualities that make them unusually difficult to study:

What makes human beings especially difficult to study?

Complexity: No galaxy, particle, molecule, or machine is as complicated as the human brain. Scientists can describe the birth of a star or the death of a cell in exquisite detail, but they can barely begin to say how the 500 million interconnected neurons that constitute the brain give rise to the thoughts, feelings, and actions that are psychology’s core concerns.

Variability: In almost all the ways that matter, one E. coli bacterium is pretty much like another. But people are as varied as their fingerprints. No two individuals ever do, say, think, or feel exactly the same thing under exactly the same circumstances, which means that when you have seen one, you have most definitely not seen them all.

Page 43Reactivity: An atom of cesium-

133 oscillates 9 192 631 770 times per second regardless of whether anyone is watching. But people often think, feel, and act one way when they are being observed and a different way when they are not. When people know they are being studied, they do not always behave as they otherwise would.

The fact that human beings are complex, variable, and reactive presents a major challenge to the scientific study of their behaviour, and psychologists have developed two kinds of methods that are designed to meet these challenges head-

Empiricism is the belief that the best way to understand the world is to observe it firsthand. It is only in the last few centuries that empiricism has come to prominence.

Empiricism is at the heart of the scientific method, which suggests that our theories about the world give rise to falsifiable hypotheses, and that we can thus make observations that test those hypotheses. The results of these tests can disprove our theories but cannot prove them.

Observation does not just mean “looking.” It requires a method. The methods of psychology are special because, more than most other natural phenomena, human beings are complex, variable, and reactive.