2.4 The Ethics of Science: First, Do No Harm

Somewhere along the way, someone probably told you that it is not nice to treat people like objects. And yet, it may seem that psychologists do just that by creating situations that cause people to feel fearful or sad, to do things that are embarrassing or immoral, and to learn things about themselves and others that they might not really want to know. Do not be fooled by appearances. The fact is that psychologists go to great lengths to protect the well-

2.4.1 Respecting People

During World War II, Nazi doctors performed truly barbaric experiments on human subjects, such as removing organs or submerging them in ice water just to see how long it would take them to die. When the war ended, the international community developed the Nuremberg Code of 1947 and then the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964, which spelled out rules for the ethical treatment of human subjects. Unfortunately, not everyone obeyed them. For example, from 1942 to 1952, the Canadian federal government conducted food and nutrition experiments on malnourished Cree communities in Northern Manitoba, and later at six Aboriginal residential schools. Some children received foods with vitamins and minerals, while others did not. At the time, no one in the communities was aware why some children were being fed products made with vitamin-

What are three features of ethical research?

Over time, the basic tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki have become increasingly enshrined in national legislation and regulations. In Canada, all research involving human persons or tissue is covered by the Tri-

The specific ethical code that psychologists follow incorporates these basic principles and expands them. (You can find the American Psychological Association’s Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct [2002] at http:/

Informed consent: Participants may not take part in a psychological study unless they have given informed consent, which is a written agreement to participate in a study made by an adult who has been informed of all the risks that participation may entail. This does not mean that the person must know everything about the study (e.g., the hypothesis), but it does mean that the person must know about anything that might potentially be harmful or painful. If people cannot give informed consent (e.g., because they are minors or are mentally incapable), then informed consent must be obtained from their legal guardians. And even after people give informed consent, they always have the right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

Freedom of consent: Psychologists may not coerce participation. Coercion not only means physical and psychological coercion but monetary coercion as well. It is unethical to offer people large amounts of money to persuade them to do something that they might otherwise decline to do. University students may be invited to participate in studies as part of their training in psychology, but they are ordinarily offered the option of learning the same things by other means.

Protection for vulnerable persons: Psychologists must take every possible precaution to protect their research participants from physical or psychological harm. If there are two equally effective ways to study something, the psychologist must use the safer method. If no safe method is available, the psychologist may not perform the study.

Risk–

benefit analysis: Although participants may be asked to accept small risks, such as a minor shock or a small embarrassment, they may not even be asked to accept large risks, such as severe pain, psychological trauma, or any risk that is greater than the risks they would ordinarily take in their everyday lives. Furthermore, even when participants are asked to take small risks, the psychologist must first demonstrate that these risks are outweighed by the social benefits of the new knowledge that might be gained from the study.Deception: Psychologists may only use deception when it is justified by the study’s scientific, educational, or applied value and when alternative procedures are not feasible. They may never deceive participants about any aspect of a study that could cause them physical or psychological harm or pain.

Debriefing: If a participant is deceived in any way before or during a study, the psychologist must provide a debriefing, which is a verbal description of the true nature and purpose of a study. If the participant was changed in any way (e.g., made to feel sad), the psychologist must attempt to undo that change (e.g., ask the person to do a task that will make him or her happy) and restore the participant to the state he or she was in before the study.

Confidentiality: Psychologists are obligated to keep private and personal information obtained during a study confidential.

These are just some of the rules that psychologists must follow. But how are those rules enforced? Almost all psychology studies are done by psychologists who work at colleges and universities. These institutions have research ethics boards (REBs) that are composed of instructors and researchers, university staff, and laypeople from the community (e.g., business leaders or members of the clergy). If the research is federally funded (as much research is), then the law requires that the REB consist of at least five people, including an ethics expert, a legal expert, and a community member who is not affiliated with the institution. A psychologist may conduct a study only after the REB has reviewed and approved it.

As you can imagine, the code of ethics and the procedure for approval are so strict that many studies simply cannot be performed anywhere, by anyone, at any time. For example, psychologists would love to know how growing up without exposure to language affects a person’s subsequent ability to speak and think, but they cannot ethically manipulate that variable in an experiment. They can only study the natural correlations between language exposure and speaking ability, and so may never be able to firmly establish the causal relationships between these variables. Indeed, there are many questions that psychologists will never be able to answer definitively because doing so would require unethical experiments that violate basic human rights.

2.4.2 Respecting Animals

What steps must psychologists take to protect nonhuman subjects?

Not all research participants have human rights because not all research participants are human. Some are chimpanzees, rats, pigeons, or other nonhuman animals. The Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC) is the national organization responsible for establishing standards for the ethical use and care of animals in research. It describes the special rights of these nonhuman participants, and provides guidelines that all research must follow. The Three Rs tenet (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) guides the ethical use of animals in science, ensuring appropriate consideration of the animals’ comfort, health, and humane treatment.

Replacement: Researchers have to prove that there is no alternative to using animals in research and that the use of animals is justified by the scientific or clinical value of the study.

Reduction: Researchers must use the fewest number of animals possible to achieve the research.

Refinement: Procedures must be modified to minimize discomfort, infection, illness, and pain of animals. This requires that animals be treated humanely, with comfortable housing and the ability to satisfy their basic instincts, (for example, mice have to make nests), and appropriate administration of painkillers.

These rules are good—

We have seen our cars and homes firebombed or flooded, and we have received letters packed with poisoned razors and death threats via e-

Where do most people stand on this issue? The majority of Canadians consider it morally acceptable to use nonhuman animals in research and say they would reject a governmental ban on such research (Gallup poll: Kiefer, 2003). Indeed, most Canadians eat meat, wear leather, and support the rights of hunters, which is to say that most Candians see a sharp distinction between animal and human rights. Science is not in the business of resolving moral controversies, and every individual must draw his or her own conclusions about this issue. But whatever position you take, it is important to note that only a small percentage of psychological studies involve animals, and only a small percentage of those studies cause animals pain or harm. Psychologists mainly study people, and when they do study animals, they mainly study their behaviour.

2.4.3 Respecting Truth

Research ethics boards ensure that data are collected ethically. But once the data are collected, who ensures that they are ethically analyzed and reported? No one does. Psychology, like all sciences, works on the honour system. No authority is charged with monitoring what psychologists do with the data they have collected, and no authority is charged with checking to see if the claims they make are true. You may find that a bit odd. After all, we do not use the honour system in stores (“Take the television set home and pay us next time you are in the neighborhood”), banks (“No need to look up your account, just tell me how much money you want to withdraw”), or courtrooms (“If you say you are innocent, well then, that is good enough for me”), so why would we expect it to work in science? Are scientists more honest than everyone else?

Definitely! Okay, we just made that up. But the honour system does not depend on scientists being especially honest, but on the fact that science is a community enterprise. When scientists claim to have discovered something important, other scientists do not just applaud, they start studying it too. When physicist Jan Hendrik Schön announced in 2001 that he had produced a molecular-

What are psychologists expected to do when they report the results of their research?

What exactly are psychologists on their honour to do? At least three things. First, when they write reports of their studies and publish them in scientific journals, psychologists are obligated to report truthfully on what they did and what they found. They cannot fabricate results (e.g., claiming to have performed studies that they never really performed) or fudge results (e.g., changing records of data that were actually collected), and they cannot mislead by omission (e.g., by reporting only the results that confirm their hypothesis and saying nothing about the results that do not). Second, psychologists are obligated to share credit fairly by including as co-

Research ethics boards ensure that scientific research that uses human subjects is based on the principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice.

Psychologists are obligated to uphold these principles by getting free informed consent from participants, protecting participants from harm, weighing benefits against risks, avoiding deception, and keeping information confidential.

Psychologists are obligated to respect the rights of animals and treat them humanely.

Psychologists are obligated to tell the truth about their studies, to share credit appropriately, and to grant others access to their data.

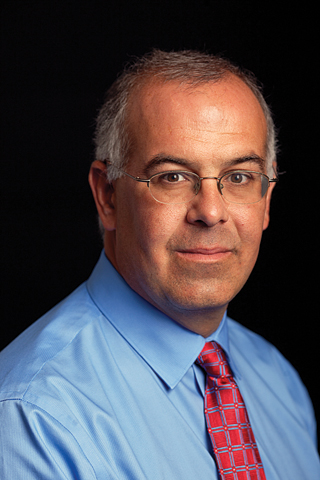

OTHER VOICES: Can We Afford Science?

Who pays for all the research described in textbooks like this one? The answer is you. By and large, scientific research is funded by governmental agencies, such as the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), which give scientists grants (also known as money) to do particular research projects that the scientists proposed. Of course, this money could be spent on other things, for example, feeding the poor, housing the homeless, caring for the ill and elderly, and so on. Does it make sense to spend taxpayer dollars on psychological science when some of our fellow citizens are cold and hungry?

American journalist and author David Brooks (2011) argued that research in the behavioural sciences in not an expenditure—

Over the past 50 years, we’ve seen a number of gigantic policies produce disappointing results—

Fortunately, today we are in the middle of a golden age of behavioral research. Thousands of researchers are studying the way actual behavior differs from the way we assume people behave. They are coming up with more accurate theories of who we are, and scores of real-

When you renew your driver’s license, you have a chance to enroll in an organ donation program. In countries like Germany and the U.S., you have to check a box if you want to opt in. Roughly 14 percent of people do. But behavioral scientists have discovered that how you set the defaults is really important. So in other countries, like Poland or France, you have to check a box if you want to opt out. In these countries, more than 90 percent of people participate.

This is a gigantic behavior difference cued by one tiny and costless change in procedure.

Yet in the middle of this golden age of behavioral research, there is a bill working through [the American] Congress that would eliminate the National Science Foundation’s Directorate for Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences. This is exactly how budgets should not be balanced—

Let’s say you want to reduce poverty. We have two traditional understandings of poverty. The first presumes people are rational. They are pursuing their goals effectively and do not need much help in changing their behavior. The second presumes that the poor are afflicted by cultural or psychological dysfunctions that sometimes lead them to behave in shortsighted ways. Neither of these theories has produced much in the way of effective policies.

Eldar Shafir of Princeton and Sendhil Mullainathan of Harvard have recently, with federal help, been exploring a third theory, that scarcity produces its own cognitive traits.

A quick question: What is the starting taxi fare in your city? If you are like most upper-

These questions impose enormous cognitive demands. The brain has limited capacities. If you increase demands on one sort of question, it performs less well on other sorts of questions.

Shafir and Mullainathan gave batteries of tests to Indian sugar farmers. After they sell their harvest, they live in relative prosperity. During this season, the farmers do well on the I.Q. and other tests. But before the harvest, they live amid scarcity and have to think hard about a thousand daily decisions. During these seasons, these same farmers do much worse on the tests. They appear to have lower I.Q.’s. They have more trouble controlling their attention. They are more shortsighted. Scarcity creates its own psychology.

Princeton students don’t usually face extreme financial scarcity, but they do face time scarcity. In one game, they had to answer questions in a series of timed rounds, but they could borrow time from future rounds. When they were scrambling amid time scarcity, they were quick to borrow time, and they were nearly oblivious to the usurious interest rates the game organizers were charging. These brilliant Princeton kids were rushing to the equivalent of payday lenders, to their own long-

Shafir and Mullainathan have a book coming out next year, exploring how scarcity—

People are complicated. We each have multiple selves, which emerge or don’t depending on context. If we’re going to address problems, we need to understand the contexts and how these tendencies emerge or do not emerge. We need to design policies around that knowledge. Cutting off financing for this sort of research now is like cutting off navigation financing just as Christopher Columbus hit the shoreline of the New World.

What do you think? Is Brooks right? Is psychological science a wise use of public funds, or is it a luxury that we simply cannot afford?

From the New York Times, July 7, 2011 © 2011 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited. http:/