10.3 Adolescence: Minding the Gap

Between childhood and adulthood is an extended developmental stage that may not qualify for a hood of its own, but that is clearly distinct from the stages that come before and after. Adolescence is the period of development that begins with the onset of sexual maturity (about 11 to 14 years of age) and lasts until the beginning of adulthood (about 18 to 21 years of age). Unlike the transition from embryo to fetus or from infant to child, this transition is sudden and clearly marked. In just 3 or 4 years, the average adolescent gains about 40 pounds and grows about 10 inches. For girls, all this growing starts at about the age of 10 and ends when they reach their full heights at about the age of 15.5. For boys, it starts at about the age of 12 and ends at about the age of 17.5.

adolescence

The period of development that begins with the onset of sexual maturity (about 11 to 14 years of age) and lasts until the beginning of adulthood (about 18 to 21 years of age).

334

The beginning of this growth spurt signals the onset of puberty, which refers to the bodily changes associated with sexual maturity. These changes involve primary sex characteristics, which are bodily structures that are directly involved in reproduction—for example, the onset of menstruation in girls and the enlargement of the testes, scrotum, and penis and the emergence of the capacity for ejaculation in boys. They also involve secondary sex characteristics, which are bodily structures that change dramatically with sexual maturity but that are not directly involved in reproduction—for example, the enlargement of the breasts and the widening of the hips in girls and the appearance of facial hair, pubic hair, underarm hair, and the lowering of the voice in both genders. This pattern of changes is caused by increased production of estrogen in girls and testosterone in boys.

puberty

The bodily changes associated with sexual maturity.

primary sex characteristics

Bodily structures that are directly involved in reproduction.

secondary sex characteristics

Bodily structures that change dramatically with sexual maturity but that are not directly involved in reproduction.

How does the brain change at puberty?

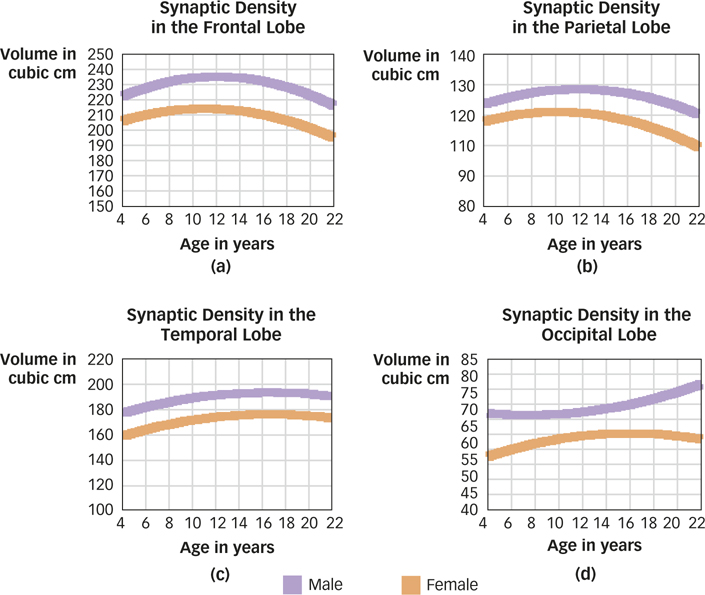

Just as the body changes during adolescence, so too does the brain. Between the ages of 6 and 13, the connections between the temporal lobe (the brain region specialized for language) and the parietal lobe (the brain region specialized for understanding spatial relations) multiply rapidly and then stop—

The Protraction of Adolescence

The age at which puberty begins varies across individuals (e.g., people tend to reach puberty at about the same age as their same-

How has the onset of puberty changed over the last century?

335

The increasingly early onset of puberty has important psychological consequences. Just two centuries ago, the gap between childhood and adulthood was relatively brief because people became physically mature at roughly the same time that they were ready to accept adult roles in society, and these roles did not normally require them to have extensive schooling. But in modern societies, people typically spend 3 to 10 years in school after they reach puberty. Thus, while the age at which people become physically adult has decreased, the age at which they are prepared or allowed to take on adult responsibilities has increased, and so the period between childhood and adulthood has become extended or protracted.

Adolescence is often characterized as a time of internal turmoil and external recklessness, and some psychologists have speculated that the protraction of adolescence is partly to blame for its sorry reputation (Epstein, 2007a; Moffitt, 1993). In some sense, adolescents are adults who have temporarily been denied a place in adult society, so they try to demonstrate their adulthood by doing things like smoking, drinking, using drugs, having sex, and committing crimes. So yes, adolescence is rough, but it is not nearly as rough as television shows might lead you to believe (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Research suggests that the “moody adolescent” who is a victim of “raging hormones” is largely a myth: Adolescents are no moodier than children (Buchanan, Eccles, & Becker, 1992), and fluctuations in their hormone levels have only a tiny impact on their moods (Brooks-

Are adolescent problems inevitable?

336

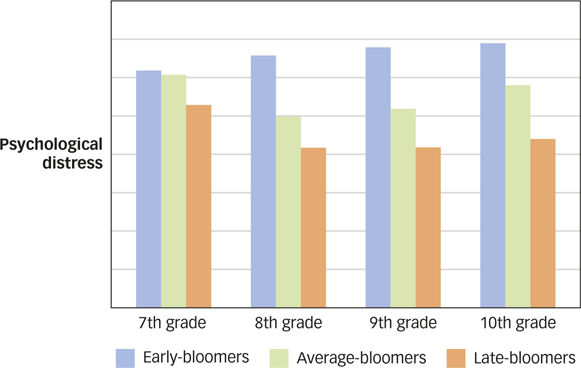

Sexuality

Puberty can be difficult, but it is especially difficult for girls who reach it earlier than their peers (Mendle, Turkheimer, & Emery, 2007; see FIGURE 10.9). Early blooming girls don’t have as much time as their peers do to develop the skills necessary to cope with adolescence (Petersen & Grockett, 1985), but because they look mature, people expect them to act like adults. They also draw the attention of older men, who may lead them into a variety of unhealthy activities (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 1996). Some research suggests that for girls, the timing of puberty has a greater influence on emotional and behavioral problems than does the occurrence of puberty itself (Buchanan et al., 1992). The timing of puberty does not have such consistent effects on boys: Some studies suggest that early maturing boys do better than their peers, some suggest they do worse, and some suggest that there is no difference at all (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 2001).

What makes adolescence especially difficult?

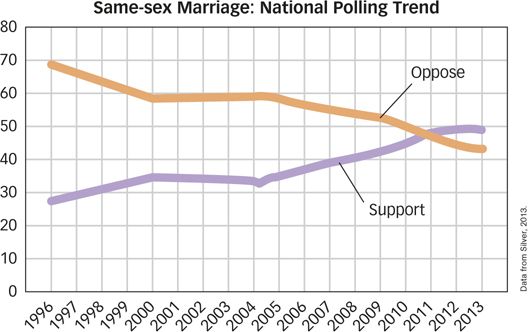

For a small minority of adolescents, puberty is additionally complicated by the fact that they are attracted to members of the same sex. Most gay men report having become aware of their sexual orientation between the ages of 6 and 18, and most gay women report having become aware between the ages of 11 and 26 (Calzo et al., 2011). Not only does their sexual orientation make gay adolescents different from the vast majority of their peers (a mere 3.5% of American adults identify themselves as lesbian, gay, or bisexual; Gates, 2011), but it can also subject them to disapproval from family, friends, and community. Americans are rapidly becoming more accepting of homosexuality (see FIGURE 10.10), but there are still plenty who disapprove. And in some nations, people do more than simply disapprove: They send gay citizens to prison or sentence them to death.

337

What determines whether a person’s sexuality is primarily oriented toward the same or the opposite sex? For a long time, psychologists believed that a person’s sexual orientation depended primarily on his or her upbringing. For example, psychoanalytic theorists claimed that boys who grow up with a domineering mother and a submissive father are less likely to identify with their father and are therefore more likely to become homosexual. But modern research has failed to identify any aspect of parenting that has a significant impact on a person’s sexual orientation (Bell, Weinberg, & Hammersmith, 1981). Perhaps the most telling fact is that children raised by homosexual couples and children raised by heterosexual couples are equally likely to become heterosexual adults (Patterson, 1995). There is also little support for the idea that a person’s early sexual encounters have a lasting impact on his or her sexual orientation (Bohan, 1996).

So what does determine a person’s sexual orientation? There is now considerable evidence to suggest that biology plays the major role. The identical twin of a gay man (with whom he shares 100% of his genes) has a 50% chance of being gay, whereas the fraternal twin or nontwin brother of a gay man (with whom he shares 50% of his genes) has only a 15% chance (Bailey & Pillard, 1991; Gladue, 1994). A similar pattern has emerged in studies of women (Bailey et al., 1993). Some evidence suggests that the fetal environment may play a role in determining sexual orientation and that high levels of androgens in the womb may predispose both male and female fetuses later to develop a sexual preference for women (Ellis & Ames, 1987; Meyer-

Is sexual orientation determined by biology or experience?

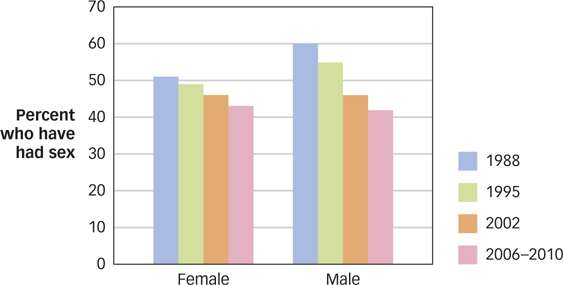

Sexual orientation may not be a matter of choice, but sexual behavior is, and many American teenagers choose it. Although the fraction of American teenagers who have had sex has declined in recent years (see FIGURE 10.11), it is still more than a third. Unfortunately, teenagers’ interest in sex typically surpasses their knowledge about it, and ignorance has consequences. A quarter of American teenagers have had four or more sexual partners by their senior year in high school, but only about half report using a condom during their last intercourse (Centers for Disease Control, 2002). Although teen birth rates have been falling in the United States for about 20 years, they are still the highest in the developed world, and consequently, so is the rate of abortion. That’s too bad, because teenage mothers fare more poorly than teenage women without children on almost every measure of academic and economic achievement, and their children fare more poorly on most measures of educational success and emotional well-

338

Why do many adolescents make unwise choices about sex?

Despite what some people believe, evidence suggests that sex education does not increase the likelihood that teenagers will have sex. Instead, sex education leads teens to delay having sex for the first time, increases the likelihood they will use birth control when they do have sex, and lowers the likelihood that they will get pregnant or catch a sexually transmitted disease (Mueller, Gavin, & Kulkarni, 2008; Satcher, 2001). Despite these documented benefits, sex education in American schools is often absent, sketchy, or based on the goal of abstinence rather than harm prevention. Alas, there is little evidence to suggest that abstinence-

Parents and Peers

Children define themselves almost entirely in terms of their relationships with parents and siblings, and adolescence marks a shift away from family relations and toward peer relations. Two things can make this shift difficult. First, although children cannot choose their parents, adolescents can choose their peers. As such, adolescents have the power to shape themselves by joining groups that will lead them to develop new values, attitudes, beliefs, and perspectives. The responsibility this opportunity entails can be overwhelming. Second, as adolescents strive for greater autonomy, their parents naturally rebel. For instance, parents and adolescents tend to disagree about the age at which certain adult behaviors—

How do family and peer relationships change during adolescence?

Studies show that across a wide variety of cultures, historical epochs, and even species, peer relations evolve in a similar way (Dunphy, 1963; Weisfeld, 1999). Young adolescents initially form groups or “cliques” with same-

339

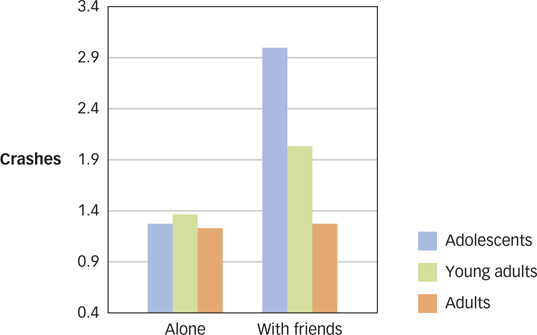

Studies show that throughout adolescence, people spend increasing amounts of time with opposite-

SUMMARY QUIZ [10.3]

Question 10.8

| 1. | Evidence indicates that American adolescents are |

- moodier than children.

- victims of raging hormones.

- likely to develop drinking problems.

- living in a protracted gap between childhood and adulthood.

d.

Question 10.9

| 2. | Scientific evidence suggests that ________ play(s) a key role in determining a person’s sexual orientation. |

- personal choices

- parenting styles

- sibling relationships

- biology

d.

Question 10.10

| 3. | Adolescents place the greatest emphasis on relationships with |

- peers.

- parents.

- siblings.

- nonparental authority figures.

a.