11.5 The Social-Cognitive Approach: Personalities in Situations

Do researchers in social cognition think that personality arises from past experiences or from the current environment?

What is it like to be a person? The social-cognitive approach is an approach that views personality in terms of how the person thinks about the situations encountered in daily life and behaves in response to them. Bringing together insights from social psychology, cognitive psychology, and learning theory, this approach emphasizes how the person experiences and interprets situations (Bandura, 1986; Mischel & Shoda, 1999; Ross & Nisbett, 1991; Wegner & Gilbert, 2000).

social-cognitive approach

An approach that views personality in terms of how the person thinks about the situations encountered in daily life and behaves in response to them.

Researchers in social cognition believe that both the current situation and learning history are key determinants of behavior. These researchers focus on how people perceive their environments, how personality contributes to the way people construct situations in their own minds, and how people’s goals and expectancies influence their responses to situations.

Consistency of Personality across Situations

At the core of the social-

person–situation controversy

The question of whether behavior is caused more by personality or by situational factors.

366

Is there no personality, then? Do we all just do what situations require? It turns out that information about both personality and situation are necessary to predict behavior accurately (Fleeson, 2004; Mischel, 2004). Some situations are particularly powerful, leading most everyone to behave similarly regardless of personality (Cooper & Withey, 2009). At a funeral, almost everyone looks somber, and during an earthquake, almost everyone shakes. But in more moderate situations, personality can come forward to influence behavior (Funder, 2001). Among the children in Hartshorne and May’s (1928) studies, cheating versus not cheating on a test was actually a fairly good predictor of cheating on a test later—

Does personality or the current situation predict a person’s behavior?

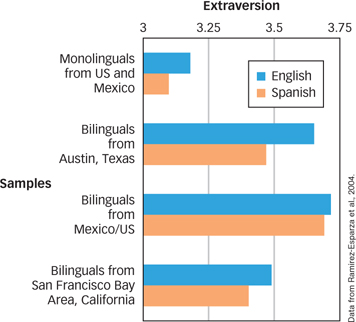

Culture & Community: Does your personality change according to which language you’re speaking?

Does your personality change according to which language you’re speaking? The personalities of people from different cultures often can diverge. For instance, in one study of personality tests taken by Americans and Mexicans, Americans reported being more extraverted, more agreeable, and more conscientious than Mexicans (Ramirez-

Interestingly, however, when the researchers tested Spanish–

367

Personal Constructs

How can we understand differences in the way situations are interpreted? George Kelly (1955) long ago realized that these differences in perspective could be used to understand the perceiver’s personality. He suggested that people view the social world from differing perspectives and that these different views arise through the application of personal constructs, dimensions people use in making sense of their experiences. Consider, for example, different individuals’ personal constructs of a clown: One person may see him as a source of fun, another as a tragic figure, and yet another as so frightening that McDonald’s must be avoided at all costs.

personal constructs

Dimensions people use in making sense of their experiences.

Why doesn’t everyone love clowns?

Kelly proposed that different personal constructs are the key to personality differences and lead people to engage in different behaviors. Taking a long break from work for a leisurely lunch might seem lazy to you. To your friend, the break might seem an ideal opportunity for catching up with friends and wonder why you always choose to eat at your desk. Social-

Personal Goals and Expectancies

Social-

People translate goals into behavior in part through outcome expectancies, a person’s assumptions about the likely consequences of a future behavior. Just as a laboratory rat learns that pressing a bar releases a food pellet, we learn that “if I am friendly toward people, they will be friendly in return” and “if I ask people to pull my finger, they will withdraw from me.” So we learn to perform behaviors that we expect will have the outcome of moving us closer to our goals. Outcome expectancies are learned through direct experience, both bitter and sweet, and through merely observing other people’s actions and their consequences. Outcome expectancies combine with a person’s goals to produce the person’s characteristic style of behavior. We do not all want the same things from life, clearly, and our personalities largely reflect the goals we pursue and the expectancies we have about the best ways to pursue them.

outcome expectancies

A person’s assumptions about the likely consequences of a future behavior.

What is the advantage of an internal locus of control?

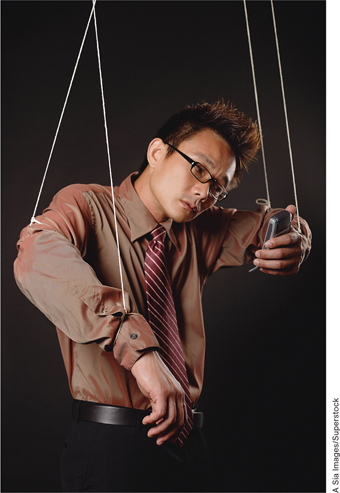

People also differ in their expectancy for achieving goals. Some people seem to feel that they are fully in control of what happens to them in life, whereas others feel that the world doles out rewards and punishments to them irrespective of their actions. A person’s locus of control is the tendency to perceive the control of rewards as internal to the self or external in the environment (Rotter, 1966). People who believe they control their own destinies are said to have an internal locus of control, whereas those who believe that outcomes are random, determined by luck, or controlled by other people are described as having an external locus of control. These beliefs translate into individual differences in emotion and behavior. For example, people with an internal locus of control tend to be less anxious, achieve more, and cope better with stress than do people with an external orientation (Lefcourt, 1982). To get a sense of your standing on this trait dimension, choose one of the options for each of the sample items from the locus-

locus of control

A person’s tendency to perceive the control of rewards as internal to the self or external in the environment.

|

For each pair of items, choose the option that most closely reflects your personal belief. |

|

|

1. |

a. Many of the unhappy things in people’s lives are partly due to bad luck. b. People’s misfortunes result from the mistakes they make. |

|

2. |

a. I have often found that what is going to happen will happen. b. Trusting to fate has never turned out as well for me as making a decision to take a definite course of action. |

|

3. |

a. Becoming a success is a matter of hard work; luck has little or nothing to do with it. b. Getting a good job depends mainly on being in the right place at the right time. |

|

4. |

a. When I make plans, I am almost certain that I can make them work. b. It is not always wise to plan too far ahead because many things turn out to be a matter of good or bad fortune anyhow. |

|

Source: Information from Rotter, 1966. Answer: A more internal locus of control would be reflected in choosing options 1b, 2b, 3a, and 4a. |

|

368

SUMMARY QUIZ [11.5]

Question 11.12

| 1. | Which of the following is NOT an emphasis of the social- |

- how personality and situation interact to cause behavior

- how personality contributes to the way people construct situations in their own minds

- how people’s goals and expectancies influence their responses to situations

- how people confront realities rather than embrace comforting illusions

d.

Question 11.13

| 2. | According to social- |

- personal constructs

- outcome expectancies

- loci of control

- personal goals

a.

Question 11.14

| 3. | Tyler has been getting poor evaluations at work. He attributes this to having a mean boss who always assigns him the hardest tasks. This suggests that Tyler has |

- external locus of control

- internal locus of control

- high performance anxiety

- poorly developed personal constructs

a.