12.1 Social Behavior: Interacting with People

Centipedes aren’t social. Neither are snails or brown bears. In fact, most animals are loners that prefer solitude to company. So why don’t we?

DATA VISUALIZATION

Dunbar’s Number and the Size of Social Networks

All animals must survive and reproduce, and being social is one strategy for accomplishing these two important goals. When it comes to finding food or fending off enemies, herds and packs and flocks can often do what individuals can’t, and that’s why over millions of years, many different species have found it useful to become social. But of the thousands and thousands of social species on our planet, only we form large-

Survival: The Struggle for Resources

To survive, an animal must find resources such as food, water, and shelter. These resources are always scarce, because if they weren’t, then the animal population would just keep increasing until they were. Animals solve the problem of scarce resources in two ways: by hurting each other and helping each other. Hurting and helping are antonyms, so you might expect them to have little in common. But as you will see, these seemingly antithetical behaviors are actually two solutions to the same problem (Hawley, 2002).

Aggression

The simplest way to solve the problem of scarce resources is simply to take what you want and kick the stuffing out of anyone who tries to stop you. Aggression is behavior whose purpose is to harm another (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Bushman & Huesmann, 2010), and it is a strategy used by just about every animal on the planet. Aggression is not something that animals do for its own sake, but as a way of getting the resources they desire. The frustration-aggression hypothesis suggests that animals aggress when their desires are frustrated (Dollard et al., 1939), and it is pretty easy to see aggression through this lens. The chimp wants the banana (desire), but the pelican is about to take it (frustration), so the chimp threatens the pelican with its fist (aggression). The robber wants the money (desire), but the teller has it all locked up (frustration), so the robber threatens the teller with a gun (aggression).

aggression

Behavior whose purpose is to harm another.

frustration-aggression hypothesis

A principle stating that animals aggress when their desires are frustrated.

381

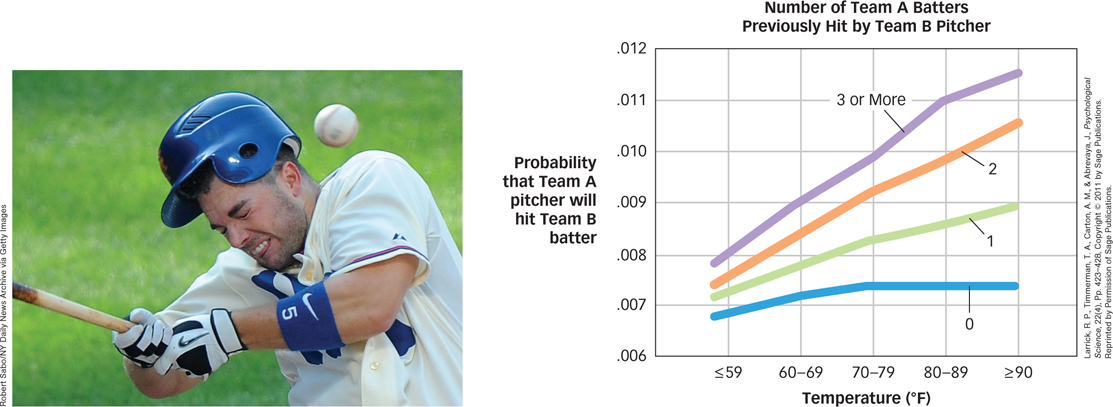

The frustration–

Larrick, R. p., Timmerman, T. A., Carton, A. M., & Abrevaya, J., sychologicalp Science, 22(4), pp. 423–

Of course, not everyone aggresses every time they feel bad. So who does and why? Research suggests that both biology and culture play important roles in determining if and when people who feel bad will aggress. Let’s start by examining biology.

Biology and Aggression. If you wanted to know whether someone was likely to aggress and you could ask them only one question, it should be this: “Are you male or female?” (Wrangham & Peterson, 1997). Violent crimes such as assault, battery, and murder are almost exclusively perpetrated by men—

One of the most reliable ways to elicit aggression in males is to challenge their status or dominance. Indeed, three quarters of all murders can be classified as “status competitions” or “contests to save face” (Daly & Wilson, 1988). Contrary to popular wisdom, it isn’t men with low self-

382

Ap photo/Jerry Larson

Under what circumstances do women aggress?

Women can be aggressive too, of course, but their aggression tends to be focused on challenges to their resources rather than to their status. Women are much less likely than men to aggress without provocation or to aggress in ways that cause physical injury, but they are only slightly less likely than men to aggress when provoked or to aggress in ways that cause psychological injury (Bettencourt & Miller, 1996; Eagly & Steffen, 1986). Indeed, women may even be more likely than men to aggress by causing social harm—

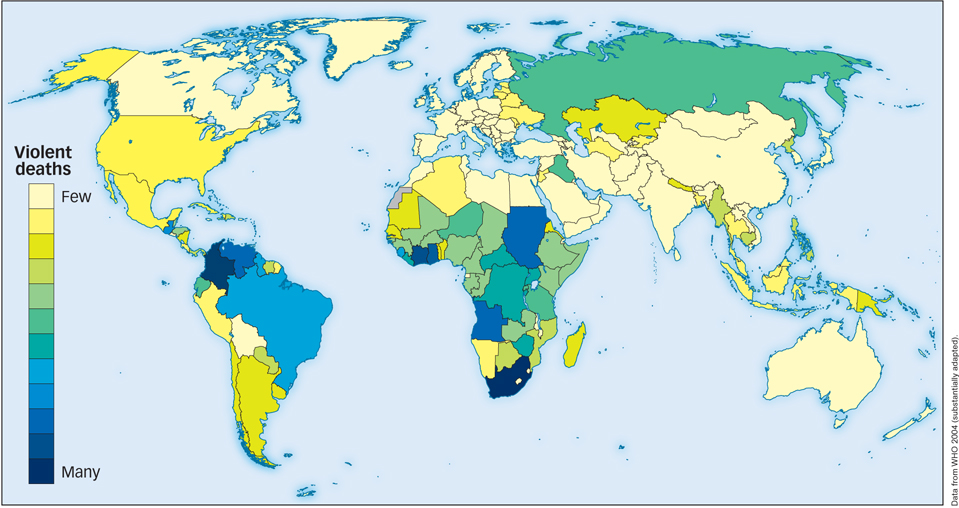

Culture and Aggression. Aggression has a biological basis, but it is also strongly influenced by culture (see FIGURE 12.2). For example, violent crime in the United States is more prevalent in the South, where traditional notions of honor require men to react aggressively when their status is challenged (Brown, Osterman, & Barnes, 2009; Nisbett & Cohen, 1996). In one set of experiments, researchers either did or did not insult American students from northern and southern states. When insulted, Southerners were more likely to experience a surge of testosterone and to feel that their status had been diminished by the insult (Cohen et al., 1996). And when a large man walked directly toward them as they were leaving the experiment, the insulted Southerners got “right up in his face” before giving way, whereas Northerners just stepped aside. On the other hand, when participants were not insulted, polite Southerners stepped aside before Northerners did. Clearly, culture plays an important role in determining whether our innate capacity for aggression will actually lead to aggressive behavior (Leung & Cohen, 2011).

Apphoto/Manish Swarup

What evidence suggests that culture can influence aggression?

383

Cooperation

Aggression is one way to solve the problem of scarce resources, but it is not the best way, because when individuals work together, they can often each get more resources than either could get alone. Cooperation is behavior by two or more individuals that leads to mutual benefit (Deutsch, 1949; Pruitt, 1998), and it is one of our species’ greatest achievements—

cooperation

Behavior by two or more individuals that leads to mutual benefit.

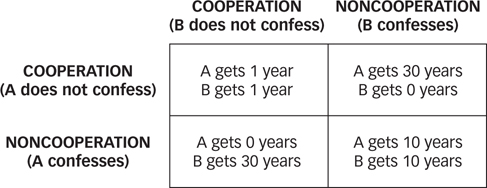

Risk and Trust. So why don’t we all cooperate all the time? Cooperation can be beneficial, but it can also be risky, and a simple game known as the prisoner’s dilemma illustrates why. Imagine that you and your friend have been arrested for hacking into a bank’s computer system and stealing a few million dollars. You are now being interrogated separately. The detectives tell you that if you and your friend both confess, you’ll each get 10 years in prison for felony theft, and if you both refuse to confess, you’ll each get 1 year in prison for disturbing the peace. However, if one of you confesses and the other doesn’t, then the one who confesses will go free and the other will be put away for 30 years. What should you do? If you study FIGURE 12.3, you’ll see that you and your friend would be wise to cooperate. If you both trust each other and both refuse to confess, then you will both get light sentences. But if you trust your friend and then your friend double-

The prisoner’s dilemma game illustrates a basic fact: Cooperation benefits everyone, but only if everyone cooperates. If someone doesn’t cooperate, then everyone else pays a price. This fact makes it hard for us to decide whether we should or should not cooperate. We know that if everyone pays their taxes, then the tax rate stays low, and everyone enjoys the benefits of sturdy bridges and first-

384

What makes cooperation risky?

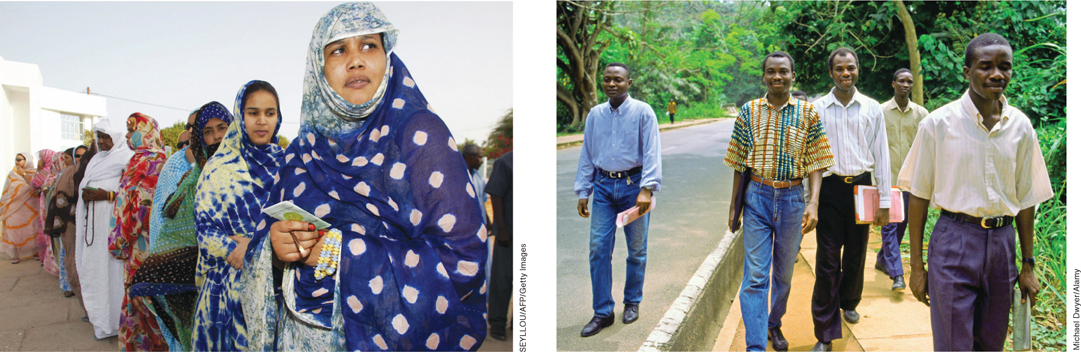

Groups and Favoritism. In fact, there is. A group is a collection of people who have something in common that distinguishes them from others, and every one of us is a member of many groups—

group

A collection of people who have something in common that distinguishes them from others.

prejudice

A positive or negative evaluation of another person based on the person’s group membership.

discrimination

Positive or negative behavior toward another person based on the person’s group membership.

What is the difference between prejudice and discrimination?

The ability to trust and cooperate is one of the main benefits of being in a group. But groups also have costs. For example, when groups try to make decisions, they rarely do better than the best member would have done alone—

common knowledge effect

The tendency for group discussions to focus on information that all members share.

group polarization

The tendency for groups to make decisions that are more extreme than any member would have made alone.

groupthink

The tendency for groups to reach consensus in order to facilitate interpersonal harmony.

385

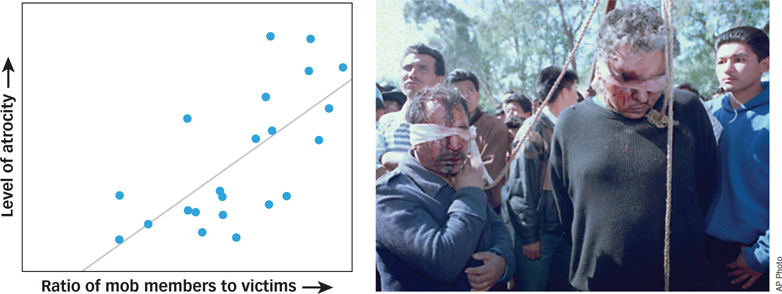

The costs of groups go beyond bad decisions. People in groups sometimes do terrible things that they would never do alone, such as rioting, lynching, and gang-

What are the costs of groups?

One reason is deindividuation, which occurs when immersion in a group causes people to become less aware of their individual values. We may wish we could grab the Rolex from the jeweler’s window or plant a kiss on the attractive stranger in the library, but we don’t do these things because they conflict with our personal values. Research shows that being assembled in groups draws our attention to others and away from ourselves, and as a result, we are less likely to consider our own personal values and instead adopt the group’s values (Postmes & Spears, 1998).

deindividuation

A phenomenon that occurs when immersion in a group causes people to become less aware of their individual values.

A second reason why groups behave badly is diffusion of responsibility, which refers to the tendency for individuals to feel diminished responsibility for their actions when they are surrounded by others who are acting the same way. For example, studies of bystander intervention— which is the act of helping strangers in an emergency situation—reveal that people are less likely to help an innocent person in distress when there are many other bystanders present, because they assume that one of the other bystanders is more responsible than they are (Darley & Latané, 1968; Latané & Nida, 1981). If you saw a fellow student cheat on an exam, you’d probably feel more responsible for reporting the incident if you were taking the test in a group of 3 than in a group of 3,000 (see FIGURE 12.4).

diffusion of responsibility

The tendency for individuals to feel diminished responsibility for their actions when they are surrounded by others who are acting the same way.

bystander intervention

The act of helping strangers in an emergency situation.

If groups make bad decisions and foster bad behavior, then might we be better off without them? It seems unlikely. Not only do groups enable cooperation, which has extraordinary benefits, but one of the best predictors of a person’s general well-

386

Altruism

So far, the picture we’ve painted of human beings isn’t all that rosy: People aggress against each other in order to get resources, and they cooperate when doing so provides them with greater benefits than aggression does. Okay, sure, we all like benefits. But aren’t we ever just nice to each other?

Altruism is behavior that benefits another without benefiting oneself, and for centuries, scientists and philosophers have argued about whether people are ever truly altruistic. That might seem like an odd argument to have. After all, people give their blood to the injured, their food to the homeless, and their time to the elderly. We volunteer, we tithe, we donate. Isn’t that evidence of altruism?

altruism

Behavior that benefits another without benefiting oneself.

Not necessarily, because behaviors that appear to be altruistic often have hidden benefits for those who do them. For example, ground squirrels make a loud noise when they see a predator, which attracts the predator’s attention and puts them at increased risk of being eaten, but which allows their fellow squirrels to escape. Although this behavior appears to be altruistic, it actually isn’t because the helpers are genetically related to the helpees. Any animal that promotes the survival of its relatives is actually promoting the survival of its own genes (Hamilton, 1964). Kin selection is the process by which evolution selects for individuals who cooperate with their relatives, and cooperating with related individuals is not truly altruistic. Cooperating with unrelated individuals isn’t necessarily altruistic either. Male baboons will risk injury to help an unrelated male baboon win a fight, and monkeys will spend time grooming unrelated monkeys when they could be doing something more interesting (which is just about anything). But as it turns out, the animals that give favors tend to get favors in return. Reciprocal altruism is behavior that benefits another with the expectation that those benefits will be returned in the future, and despite the second word in this term, it isn’t truly altruistic (Trivers, 1972). Indeed, reciprocal altruism is merely cooperation extended over time.

kin selection

The process by which evolution selects for individuals who cooperate with their relatives.

reciprocal altruism

Behavior that benefits another with the expectation that those benefits will be returned in the future.

© Marty Katz/

Are human beings ever truly altruistic?

The behavior of nonhuman animals provides little evidence of genuine altruism (cf. Bartal, Decety, & Mason, 2011). But what about us? Are we any different? Like other animals, we tend to help our kin more than we help strangers (Burnstein, Crandall, & Kitayama, 1994; Komter, 2010), and we tend to expect those we help to help us in return (Burger et al., 2009). But unlike other animals, we do sometimes provide benefits to complete strangers who have no chance of repaying us (Batson, 2002; Warneken & Tomasello, 2009). We hold the door for people who share precisely none of our genes and tip waiters in restaurants to which we will never return. And we do more than that. As the World Trade Center burned on the morning of September 11, 2001, civilians in sailboats headed toward the destruction rather than away from it, initiating the largest waterborne evacuation in U.S. history. As one observer remarked, “If you’re out on the water in a pleasure craft and you see those buildings on fire, in a strictly rational sense you should head to New Jersey. Instead, people went into potential danger and rescued strangers” (Dreifus, 2003). Human beings can be truly altruistic, and some studies suggest that they are even more altruistic than they realize (Miller & Ratner, 1998).

387

Reproduction: The Quest for Immortality

All animals must survive and reproduce, and social behavior is useful for survival. But it is an absolute prerequisite for reproduction, which doesn’t happen until people get very, very social. The first step on the road to reproduction is finding someone who wants to travel that road with us. How do we do that?

Selectivity

Dr. paul Zahl/photo Researchers

With the exception of a few well-

Why are women choosier than men?

One reason for this is that our basic biology makes sex a riskier proposition for women than for men. Men produce billions of sperm in their lifetimes, their ability to conceive a child tomorrow is not inhibited by having conceived one today, and conception has no significant physical costs. On the other hand, women produce a small number of eggs in their lifetimes, conception eliminates their ability to conceive for at least 9 more months, and pregnancy produces physical changes that increase women’s nutritional requirements and put them at risk of illness and death. Therefore, if a man mates with a woman who does not produce healthy offspring or who won’t do her part to raise the children, he’s lost nothing but 10 minutes and a teaspoon of bodily fluid. But if a woman makes the same mistake, she has lost a precious egg, borne the costs of pregnancy, risked her life in childbirth, and missed at least 9 months of other reproductive opportunities.

So basic biology pushes women to be choosier then men. But culture and experience can push equally hard, and in a different direction (Petersen & Hyde, 2010; Zentner, & Mitura, 2012). For example, women may be choosier than men simply because they are approached more often (Conley et al., 2011) or because the reputational costs of promiscuity are higher (Eagly & Wood, 1999; Kasser & Sharma, 1999). Indeed, when sex becomes expensive for men (e.g., when they are choosing a long-

388

The Real World: Making the Move

Making the Move

When it comes to selecting romantic partners, women tend to be choosier than men, and most scientists think that it has a lot to do with differences in their reproductive biology. But it might also have something to do with the nature of the courtship dance itself.

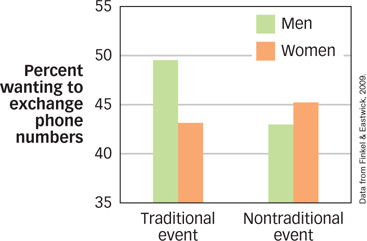

When it comes to approaching a potential romantic partner, the person with the most interest should be most inclined to “make the first move.” Of course, in most cultures, men are expected to make the first move. Could it be that making the first move causes men to think that they have more interest than women do?

To find out, researchers created two kinds of speed dating events (Finkel & Eastwick, 2009). In the traditional event, the women stayed in their seats, and the men moved around the room, stopping to spend a few minutes chatting with each woman. In the nontraditional event, the men stayed in their seats, and the women moved around the room, stopping to spend a few minutes chatting with each man. When the event was over, the researchers asked each man and woman privately whether they wanted to exchange phone numbers with any of the potential partners they’d met.

The results were striking (see the accompanying figure). When men made the move (as they traditionally do), women were the choosier gender. That is, men wanted to get a lot more phone numbers than women wanted to give. But when women made the move, men were the choosier gender, and women asked for more numbers than men were willing to hand over. Apparently, approaching someone makes us eager, and being approached makes us cautious. One reason why women are typically the choosier gender may simply be that in most cultures, men are expected to make the first move.

Attraction

For most of us, there is a very small number of people with whom we are willing to have sex, an even smaller number of people with whom we are willing to have children, and a staggeringly large number of people with whom we are unwilling to have either. So when we meet someone new, how do we decide which of these categories the person belongs in? Many things go into choosing a date, a lover, or a partner for life, but perhaps none is more important than the simple feeling we call attraction (Berscheid & Reis, 1998). Research suggests that this feeling is caused by situational, physical, and psychological factors. Let’s examine them in turn.

Situational Factors. We tend to think that we select our romantic partners on the basis of their personalities, appearances, and so on—

389

Proximity provides something else as well. Every time we encounter a person, that person becomes a bit more familiar to us, and people generally prefer familiar to novel stimuli. The mere exposure effect is the tendency for liking to increase with the frequency of exposure (Bornstein, 1989; Zajonc, 1968). For instance, in some experiments, geometric shapes, faces, or alphabetical characters were flashed on a computer screen so quickly that participants were unaware of having seen them. Participants were then shown some of the “old” stimuli that had been flashed on the screen as well as some “new” stimuli that had not. Although they could not reliably say which stimuli were old and which were new, the participants did tend to like the old stimuli better than the new ones (Monahan, Murphy, & Zajonc, 2000). Although there are some circumstances under which “familiarity breeds contempt” (Norton, Frost, & Ariely, 2007), for the most part, it tends to breed liking (Reis et al., 2011).

mere exposure effect

The tendency for liking to increase with the frequency of exposure.

Why does proximity influence attraction?

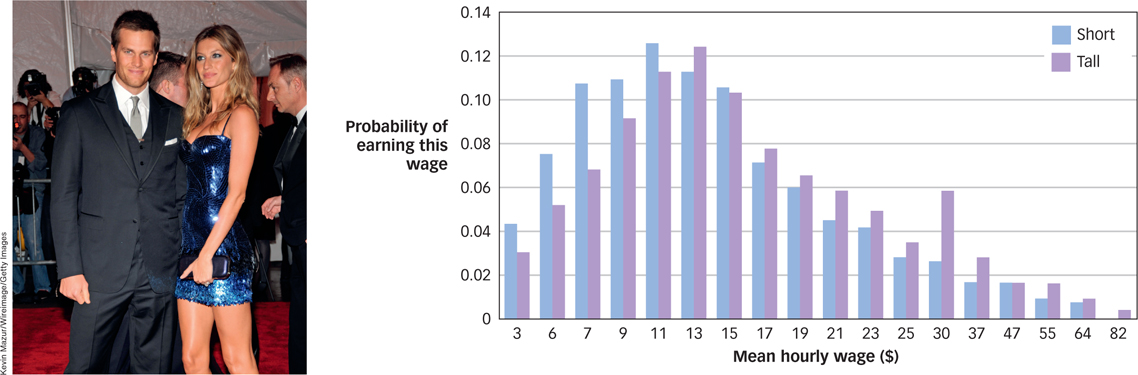

Physical Factors. One of the strongest determinants of attraction is a person’s physical appearance. One study found that a man’s height and a woman’s weight were among the best predictors of how many responses their personal ads received (Lynn & Shurgot, 1984), and another study found that physical attractiveness was the only factor that predicted the online dating choices of both women and men (Green, Buchanan, & Heuer, 1984). Good-

Why is physical appearance so important?

So yes, it pays to be beautiful. But what exactly constitutes beauty? The answer to that question varies across cultures. In the United States, for example, most women want to be slender, but in Mauritania, young girls are forced to drink up to 5 gallons of high-

390

But while different cultures have somewhat different standards of beauty, those standards also have a lot in common (Cunningham et al., 1995). For example, in all cultures, faces are generally considered more attractive when they are bilaterally symmetrical—

Michael Dwyer/Alamy

Why is similarity such a powerful determinant of attraction?

Psychological Factors. A person’s physical appearance is often the first thing we know about them, so it isn’t surprising that it determines our initial attraction (Lenton & Francesconi, 2010). But once people begin interacting, they quickly move beyond appearances (Cramer, Schaefer, & Reid, 1996; Regan, 1998). People’s inner qualities—

How much wit and wisdom do we want our mate to have? Research suggests that we are most attracted to those who are similar to us (Byrne, Ervin, & Lamberth, 1970; Byrne & Nelson, 1965; Hatfield & Rapson, 1992; Neimeyer & Mitchell, 1988). Indeed, one of the best predictors of whether two people will marry is their similarity in terms of education, religious background, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and personality (Botwin, Buss, & Shackelford, 1997; Buss, 1985; Caspi & Herbener, 1990).

391

Why is similarity so attractive? First, it’s easy to interact with people who are similar to us because we can instantly agree on a wide range of issues, such as what to eat, where to live, how to raise children, and how to spend our money. Second, when someone shares our attitudes and beliefs, we feel more confident that those attitudes and beliefs are correct, and that’s always a comfort (Byrne & Clore, 1970). Third, if we like people who share our attitudes and beliefs, then we can reasonably expect them to like us for the same reason, and being liked is a powerful source of attraction (Aronson & Worchel, 1966; Backman & Secord, 1959; Condon & Crano, 1988). Although we tend to like people who like us, it is worth noting that we especially like people who like us and who don’t like anyone else (Eastwick et al., 2007).

Relationships

Lightscapes photography, Inc./Corbis

Why do people form long-

Once we have attracted a mate, we are ready to reproduce. (Note: It is perfectly fine to pause for dinner.) Human reproduction ordinarily happens in the context of committed, long-

One answer is that we’re born half-

In most cultures, committed, long-

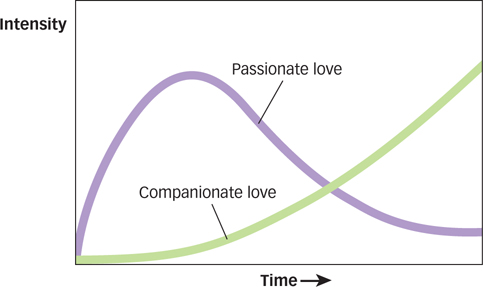

But what exactly is love? Psychologists distinguish between two basic kinds: passionate love, which is an experience involving feelings of euphoria, intimacy, and intense sexual attraction, and companionate love, which is an experience involving affection, trust, and concern for a partner’s well-

passionate love

An experience involving feelings of euphoria, intimacy, and intense sexual attraction.

companionate love

An experience involving affection, trust, and concern for a partner’s well-

392

Divorce: When the Costs Outweigh the Benefits

The most recent U.S. government census statistics indicate that for every two couples that get married, roughly one couple gets divorced. But why? Marital satisfaction is only weakly correlated with marital stability (Karney & Bradbury, 1995), suggesting that relationships break up or remain intact for reasons other than the satisfaction of those involved (Drigotas & Rusbult, 1992; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). Social exchange is the hypothesis that people remain in relationships only as long as they perceive a favorable ratio of costs to benefits (Homans, 1961; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). Relationships offer both benefits (love, sex, and financial security) and costs (responsibility, conflict, loss of freedom), and people maintain them as long as the ratio of the two is acceptable. Three things determine whether a person will find a particular cost-

social exchange

The hypothesis that people remain in relationships only as long as they perceive a favorable ratio of costs to benefits.

How do people weigh the costs and benefits of their relationships?

- The acceptableness of any cost–

benefit ratio depends on the alternatives available. For example, a cost– benefit ratio that is acceptable to two people who are stranded on a desert island might not be acceptable to the same two people if they were living in a large city where each had access to other potential partners. A cost– benefit ratio is acceptable when we feel that it is the best we can or should do. - People may want their cost–

benefit ratios to be high, but they also want them to be roughly the same as their partner’s. For example, spouses are more distressed when their respective cost– benefit ratios are different than when they are unfavorable, and this is true even when their cost– benefit ratio is more favorable than their partner’s (Schafer & Keith, 1980). - Relationships can be thought of as investments into which people pour resources such as time, money, and affection, and research suggests that once people have poured resources into a relationship, they are willing to settle for less favorable cost–

benefit ratios (Kelley, 1983; Rusbult, 1983). This is one of the reasons why people are much more likely to end new marriages than old ones (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002; Cherlin, 1992).

SUMMARY QUIZ [12.1]

Question 12.1

| 1. | Why are acts of aggression— |

- frustration

- negative affect

- resource scarcity

- biology and culture interaction

b.

393

Question 12.2

| 2. | What is the single best predictor of aggression? |

- temperament

- age

- gender

- status

c.

Question 12.3

| 3. | The prisoner’s dilemma game illustrates |

- the hypothesis-

confirming bias. - the diffusion of responsibility.

- group polarization.

- the benefits and costs of cooperation.

d.

Question 12.4

| 4. | Which of the following is NOT a downside of being in a group? |

- Groups make cooperation less risky

- Groups make people less healthy and happy.

- Groups sometimes make poor decisions.

- Groups may take extreme actions an individual member would not take alone.

a.