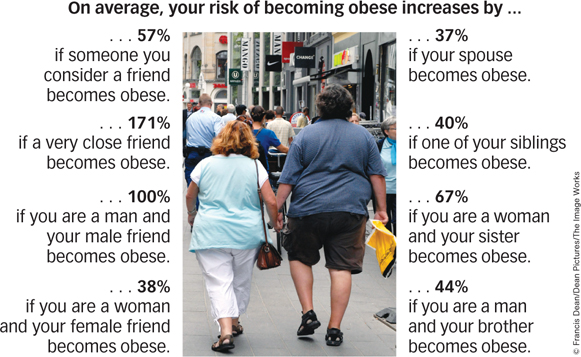

12.2 Social Influence: Controlling People

Those of us who grew up watching superhero cartoons have usually thought a bit about which of the standard superpowers we’d most like to have. Super strength and super speed have obvious benefits, invisibility could be interesting as well as lucrative, and there’s always a lot to be said for flying. But when it comes right down to it, the ability to control other people would probably be the most useful. After all, who needs to change the course of mighty rivers or bend steel in his bare hands if someone else can be convinced to do it for them? The things we want from life—

Luckily, you’ve got it! Social influence is the control of one person’s behavior by another (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004) and it happens all the time. Every one of us influences other people, and every one of us is influenced by them. The techniques we use are numerous and varied, but in the end they all rely on the fact that human beings have three basic motivations: to experience pleasure and to avoid experiencing pain (the hedonic motive), to be accepted and to avoid being rejected (the approval motive), and to believe what is right and to avoid believing what is wrong (the accuracy motive; Bargh, Gollwitzer, & Oettingen, 2010; Fiske, 2010). As you will see, most attempts at social influence appeal to one or more of these three motivations.

social influence

The control of one person’s behavior by another.

The Hedonic Motive: Pleasure Is Better Than Pain

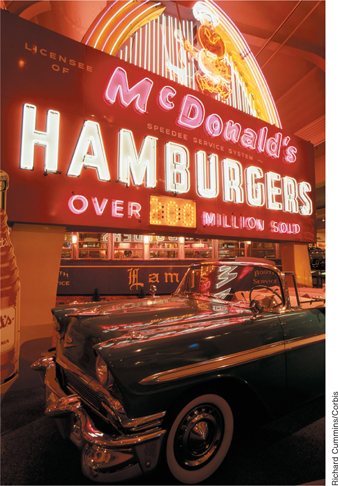

Pleasure seeking is the most basic of all motives, and social influence often involves creating situations in which others can achieve more pleasure by doing what we want them to do than by doing something else. Parents, teachers, governments, and businesses influence our behavior by offering rewards and threatening punishments (see FIGURE 12.7). There’s nothing mysterious about how these influence attempts work, and they are often quite effective. When the Republic of Singapore warned its citizens that anyone caught chewing gum in public would face a year in prison and a $5,500 fine, the rest of the world was outraged; but when the outrage subsided, it was hard to ignore the fact that gum chewing in Singapore had fallen to an all-

394

Question 12.5

Why do rewards and punishments sometimes backfire?

You’ll recall from the Learning chapter that even a sea slug will repeat behaviors that are followed by rewards and avoid behaviors that are followed by punishments. Although the same is generally true of human beings, there are some instances in which rewards and punishments can backfire. For example, children in one study were allowed to draw with colored markers. Some were given a “Good Player Award” (the “rewarded” children) and some were not (the “unrewarded” children). The next day, all of the children were again given markers, but this time no awards were offered. The results showed that the previously rewarded children drew with the markers less than the previously unrewarded children did (Lepper, Greene, & Nisbett, 1973). Why? Because previously rewarded children had come to think of drawing as something one does to get a reward—

The Approval Motive: Acceptance Is Better Than Rejection

Other people stand between us and starvation, predation, loneliness, and all the other things that make getting shipwrecked such an unpopular pastime. We depend on others for safety, sustenance, and solidarity, and so we are powerfully motivated to have others like us, accept us, and approve of us (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Leary, 2010). Like the hedonic motive, the approval motive can be a lever for social influence.

395

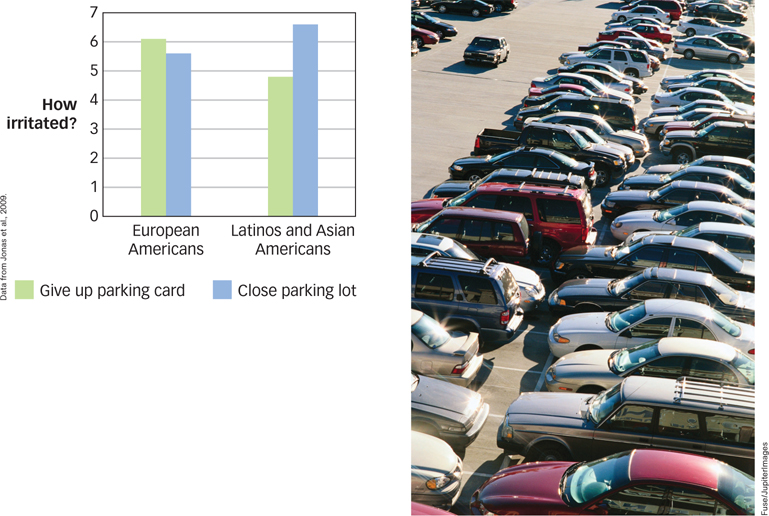

Culture & Community: Free parking.

Free parking. People don’t like to be manipulated, and they get upset when someone threatens their freedom. Is this a uniquely Western reaction? To find out, psychologists asked college students for one of two favors and then measured how irritated the students felt (Jonas et al., 2009). In one case, the psychologists asked students if they would give up their right to park on campus for a week (“Would you mind if I used your parking card so I can participate in a research project in this building?”). In the other case, the psychologists asked students if they would give up everyone’s right to park on campus for a week (“Would you mind if we closed the entire parking lot for a tennis tournament?”). How did students react to these requests?

Fuse/JupiterImages

It depended on culture. As the figure shows, European American students were more irritated by a request that limited their own freedom than by a request that limited everyone’s freedom (“If nobody can park, that’s inconvenient. But if everybody except me can park, that’s unfair!”). But Latino and Asian American students had precisely the opposite reactions (“The needs of the requestor outweigh the needs of one student, but they don’t outweigh the needs of all students”). It appears that all people value freedom—

Normative Influence

When you get on an elevator, you are supposed to face forward and not talk to the person next to you even if you were talking to that person before you got on the elevator unless you are the only two people on the elevator in which case it’s okay to talk and face sideways but still not backward. Although no one ever taught you this particularly long rule of elevator etiquette, you probably picked it up somewhere along the way. The unwritten rules that govern social behavior are called norms, which are customary standards for behavior that are widely shared by members of a culture (Cialdini, 2013; Miller & Prentice, 1996).

norms

Customary standards for behavior that are widely shared by members of a culture.

How are we influenced by other people’s behavior?

We learn norms with exceptional ease and we obey them with exceptional fidelity because we know that if we don’t, others won’t approve of us. For example, every human culture has a norm of reciprocity, which is the unwritten rule that people should benefit those who have benefited them (Gouldner, 1960). When a friend buys you lunch, you must eventually return the favor; and if you don’t, your friend will eventually get a new one. Indeed, the norm of reciprocity is so strong that when researchers randomly pulled the names of strangers from a telephone directory and sent them all Christmas cards, they received Christmas cards back from most (Kunz & Woolcott, 1976).

norm of reciprocity

The unwritten rule that people should benefit those who have benefited them.

Norms can be a powerful tool for social influence. Normative influence is a phenomenon that occurs when another person’s behavior provides information about what is appropriate (see FIGURE 12.8). For example, waiters and waitresses know all about the norm of reciprocity, and so they often give customers a piece of candy along with the bill, hoping that customers who receive a free candy will feel obligated to do “a little extra” for the server who did “a little extra” for them. Research shows that this little trick works quite nicely (Strohmetz et al., 2002).

normative influence

A phenomenon that occurs when another person’s behavior provides information about what is appropriate.

396

Conformity

People can influence us by invoking familiar norms, such as the norm of reciprocity. But if you’ve ever found yourself in a fancy restaurant, sneaking a peek at the person next to you in the hopes of discovering whether the little fork is meant to be used for shrimp or salad, then you know that other people can also influence us by defining new norms in ambiguous, confusing, or novel situations. Conformity is the tendency to do what others do simply because others are doing it, and it results in part from normative influence.

conformity

The tendency to do what others do simply because others are doing it.

Why do we do what we see other people doing?

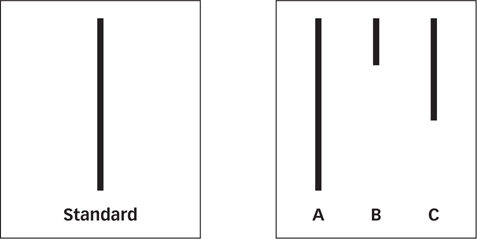

In a classic study, male participants sat in a room with seven other men who appeared to be ordinary participants but who were actually trained actors (Asch, 1951, 1956). An experimenter explained that the participants would be shown cards with three printed lines and that his job was simply to say which of the three lines matched a “standard line” that was printed on another card (see FIGURE 12.9). The experimenter held up a card and then asked each man to answer in turn. The real participant was among the last to be called on. Everything went well on the first two trials, but then on the third trial something really strange happened: The actors all began giving the same wrong answer! What did the real participants do? Seventy-

397

Other Voices: 91% of All Students Read This Box and Love It

91% of All Students Read This Box and Love It

Binge drinking is a problem on college America (Wechsler & Nelson, 2001). About half of all students report doing it, and those who do are much more likely to miss classes, get behind in their school work, drive drunk, and have unprotected sex. So what to do?

Colleges have tried a number of remedies—

… Like most universities, Northern Illinois University in DeKalb has a problem with heavy drinking. In the 1980s, the school was trying to cut down on student use of alcohol with the usual strategies. One campaign warned teenagers of the consequences of heavy drinking. “It was the ‘don’t run with a sharp stick you’ll poke your eye out’ theory of behavior change,” said Michael Haines, who was the coordinator of the school’s Health Enhancement Services. When that didn’t work, Haines tried combining the scare approach with information on how to be well: “It’s O.K. to drink if you don’t drink too much—

That one failed, too. In 1989, 45 percent of students surveyed said they drank more than five drinks at parties. This percentage was slightly higher than when the campaigns began. And students thought heavy drinking was even more common; they believed that 69 percent of their peers drank that much at parties.

But by then Haines had something new to try. In 1987 he had attended a conference on alcohol in higher education sponsored by the United States Department of Education. There Wes Perkins, a professor of sociology at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Alan Berkowitz, a psychologist in the school’s counseling center, presented a paper that they had just published on how student drinking is affected by peers. “There are decades of research on peer influence—

The “aha!” conclusion Perkins and Berkowitz drew was this: maybe students’ drinking behavior could be changed by just telling them the truth.

Haines surveyed students at Northern Illinois University and found that they also had a distorted view of how much their peers drink. He decided to try a new campaign, with the theme “most students drink moderately.” The centerpiece of the campaign was a series of ads in the Northern Star, the campus newspaper, with pictures of students and the caption “two thirds of Northern Illinois University students (72%) drink 5 or fewer drinks when they ‘party’.”…

Haines’s staff also made posters with campus drinking facts and told students that if they had those posters on the wall when an inspector came around, they would earn $5. (35 percent of the students did have them posted when inspected.) Later they [the staff members] made buttons for students in the fraternity and sorority system—

After the first year of the social norming campaign, the perception of heavy drinking had fallen from 69 to 61 percent. Actual heavy drinking fell from 45 to 38 percent. The campaign went on for a decade, and at the end of it NIU students believed that 33 percent of their fellow students were episodic heavy drinkers, and only 25 percent really were—

Why isn’t this idea more widely used? One reason is that it can be controversial. Telling college students “most of you drink moderately” is very different [from] saying “don’t drink.” (It’s so different, in fact, that the National Social Norms Institute, with headquarters at the University of Virginia, gets its money from Anheuser Busch—

Social norming is a powerful but controversial tool for changing behavior. When we tell students about drinking on campus, should we tell them what’s true (even if the truth is a bit ugly) or should we tell them what’s best (even if they are unlikely to do it)?

From the New York Times, March 27, 2013. © 2013 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited. http:/

Obedience

In most situations, there are a few people whom we all recognize as having special authority both to define the norms and to enforce them. The guy who works at the movie theater may be some high school fanboy with a bad haircut and a 10:00 p.m. curfew, but in the theater he has authority. So when he asks you to stop texting in the middle of the movie, you do as you are told. Obedience is the tendency to do what authorities tell us to do.

obedience

The tendency to do what powerful authorities tell us to do.

398

Why do we do what others tell us to do?

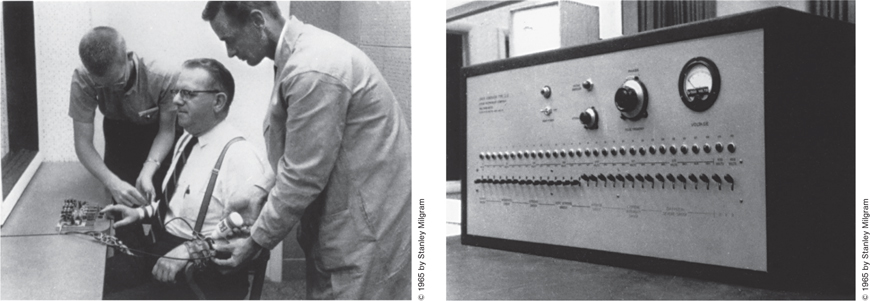

Why do we obey authorities? Well, yes, sometimes they have guns. But while authorities are often capable of rewarding and punishing us, research shows that much of their influence is normative (Tyler, 1990). Psychologist Stanley Milgram (1963) demonstrated this in one of psychology’s most infamous experiments. The participants in this experiment met a middle-

© 1965 by Stanley Milgram

After the learner was strapped into his chair, the experiment began. When the learner made his first mistake, the participant dutifully delivered a 15-

Would normal people electrocute a stranger just because some guy in a lab coat told them to? The answer, it seems, is yes—as long as normal means being sensitive to norms. The participants in this experiment knew that hurting others is not always wrong: Doctors give painful injections, and teachers give painful exams. There are many situations in which it is permissible to cause someone to suffer. The experimenter’s calm demeanor and persistent instruction suggested that he—

399

The Accuracy Motive: Right Is Better Than Wrong

If you know just two things—

attitude

An enduring positive or negative evaluation of an object or event.

belief

An enduring piece of knowledge about an object or event.

Informational Influence

In what ways are we constant targets of informational influence?

If everyone in the mall suddenly ran screaming for the exit, you’d probably join the stampede—

informational influence

A phenomenon that occurs when another person’s behavior provides information about what is true.

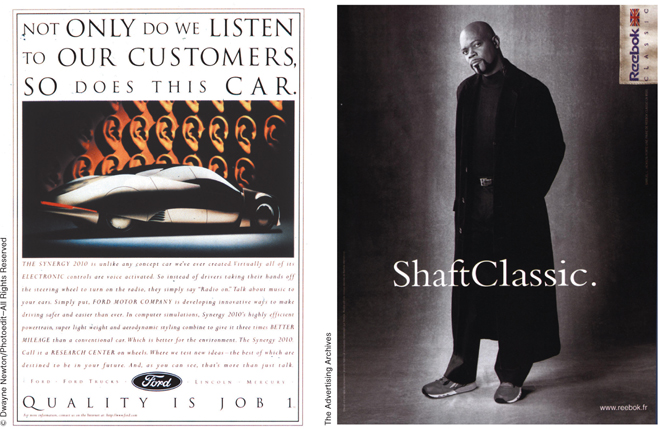

You are the constant target of informational influence. When a salesperson tells you that “most people buy the iPad with extra memory,” she is artfully suggesting that you should take other people’s behavior as information about the product. Advertisements that refer to soft drinks as “popular” or books as “best sellers” are reminding you that other people are buying these particular drinks and books, which suggests that they know something you don’t and that you’d be wise to follow their example. Situation comedies provide laugh tracks because the producers know that when you hear other people laughing, you will mindlessly assume that something must be funny (Fein, Goethals, & Kugler, 2007; Nosanchuk & Lightstone, 1974). Bars and nightclubs make people stand in line even when there is plenty of room inside because the owners of these establishments know that passersby will see the line and assume that the club is worth waiting for. In short, the world is full of objects and events about which we know little, and we can often cure our ignorance by paying attention to the way in which others are acting toward them.

Persuasion

The Advertising Archives

Persuasion is a phenomenon that occurs when a person’s attitudes or beliefs are influenced by a communication from another person (Albarracín & Vargas, 2010; Petty & Wegener, 1998). How does it work? When the next presidential election rolls around, the candidates will promise to persuade you to vote for them by demonstrating that their positions on the issues are the most practical, intelligent, fair, and beneficial. Having made that promise, they will then devote most of their financial resources to persuading you by other means—

persuasion

A phenomenon that occurs when a person’s attitudes or beliefs are influenced by a communication from another person.

systematic persuasion

The process by which attitudes or beliefs are changed by appeals to reason.

heuristic persuasion

The process by which attitudes or beliefs are changed by appeals to habit or emotion.

400

When is it more effective to appeal to reason or to emotion?

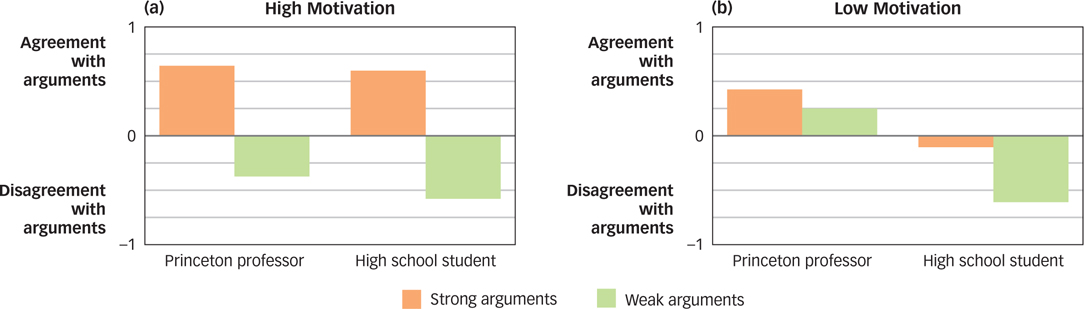

Which form of persuasion will be more effective? That depends on whether you are willing and able to weigh evidence and analyze arguments. In one study, students heard a speech that contained either strong or weak arguments in favor of instituting comprehensive exams at their school (Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman, 1981). Some students were told that the speaker was a Princeton University professor, and others were told that the speaker was a high school student—

Consistency

Why do we care about being consistent?

If a friend told you that rabbits had just staged a coup in Antarctica and were halting all carrot exports, you probably wouldn’t turn on CNN. You’d know right away that your friend must be joking (or on drugs) because the statement is logically inconsistent with other things that you know are true—

401

The motivation to have consistent beliefs leaves people vulnerable to social influence. Consider the foot-in-the-door technique, which is a social influence technique that involves making a small request before making a large request (Burger, 1999). In one study (Freedman & Fraser, 1966), experimenters went to a neighborhood and knocked on doors to see if they could convince homeowners to let them install a big, ugly “Drive Carefully” sign in their front yards. One group of homeowners was simply asked if they would allow the ugly sign to be installed, and only 17% said yes. A second group of homeowners was first asked to sign a petition urging the state legislature to promote safe driving (which almost all agreed to do) and was then asked to allow the installation of the ugly sign. And 55% said yes! Why would homeowners be more likely to grant two requests than one?

foot-in-the-door technique

A social influence technique that involves making a small request before making a large request.

Just imagine how the homeowners in the second group felt. They had just signed a petition stating that they thought safe driving was important, but they really didn’t want an ugly sign in their front yards. And yet, saying yes to the petition and no to the sign would be obviously inconsistent. As they wrestled with this dilemma, they probably began to experience a feeling called cognitive dissonance, which is an unpleasant state that arises when a person recognizes the inconsistency of his or her actions, attitudes, or beliefs (Festinger, 1957). When people experience cognitive dissonance, they naturally try to alleviate it, and one way to alleviate cognitive dissonance is to restore consistency among one’s actions, attitudes, and beliefs (Aronson, 1969; Cooper & Fazio, 1984). Allowing the ugly sign to be installed in their yards accomplished that goal. Recent research shows that this phenomenon can be used to good effect: Hotel guests who were asked at check-

cognitive dissonance

An unpleasant state that arises when a person recognizes the inconsistency of his or her actions, attitudes, or beliefs.

What happens when we are inconsistent?

We are motivated to be consistent, but there are inevitably times when we just can’t be—

For example, participants in one study were asked to perform a dull task that involved turning knobs one way, then the other way, and then back again. After the participants were sufficiently bored, the experimenter explained that he desperately needed a few more people to volunteer for the study, and he asked the participants to go into the hallway, find another person, and tell that person that the knob-

402

SUMMARY QUIZ [12.2]

Question 12.6

| 1. | The ___________ motive describes how people are motivated to experience pleasure and to avoid experiencing pain. |

- emotional

- accuracy

- approval

- hedonic

d.

Question 12.7

| 2. | The tendency to do what authorities tell us to do is known as |

- persuasion.

- obedience.

- conformity.

- the self-

fulfilling prophecy.

b.

Question 12.8

| 3. | Andrea and Jeff had to wait in line for over an hour to get into an exclusive restaurant. Despite being served a mediocre meal, they glowingly praised the restaurant to their friends. This behavior was probably a result of |

- conformity

- the norm of reciprocity

- the foot in the door technique

- cognitive dissonance

d.