13.2 Stress Reactions: All Shook Up

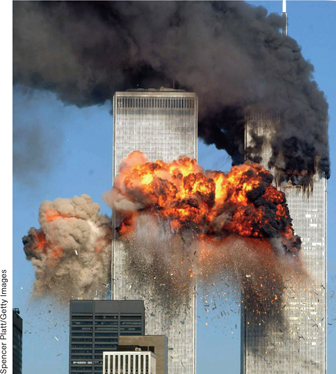

It was a regular Tuesday morning in New York City. College students were sitting in their morning classes. People were arriving at work and the streets were beginning to fill with shoppers and tourists. Then, at 8:46 a.m., American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center. People watched in horror. This seemed like a terrible accident. Then at 9:03 a.m., United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center. There were then reports of a plane crashing into the Pentagon. And another somewhere in Pennsylvania. America was under attack, and no one knew what would happen next on this terrifying morning of September 11, 2001. The terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center were an enormous stressor that had a lasting impact on many people, physically and psychologically. People living in close proximity to the World Trade Center (within 1.5 miles) during 9/11 were found to have less gray matter in the amygdala, hippocampus, insula, anterior cingulate, and medial prefrontal cortex relative to those living more than 200 miles away during the attacks, suggesting that the stress associated with the attacks may have reduced the size of these parts of the brain that play an important role in emotion, memory, and decision making (Ganzel et al., 2008). Children who watched more television coverage of 9/11 had higher symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder than children who watched less coverage (Otto et al., 2007). Stress can produce changes in every system of the body and mind, stimulating both physical reactions and psychological reactions. Let’s consider each in turn.

416

Physical Reactions

How does the body react to a fight-

The fight-or-flight response is an emotional and physiological reaction to an emergency that increases readiness for action. The mind asks, “Should I stay and battle this somehow, or should I run like mad?” And the body prepares to react. If you’re a cat at this time, your hair stands on end. If you’re a human, your hair stands on end, too, but not as visibly.

fight-or-flight response

An emotional and physiological reaction to an emergency that increases readiness for action.

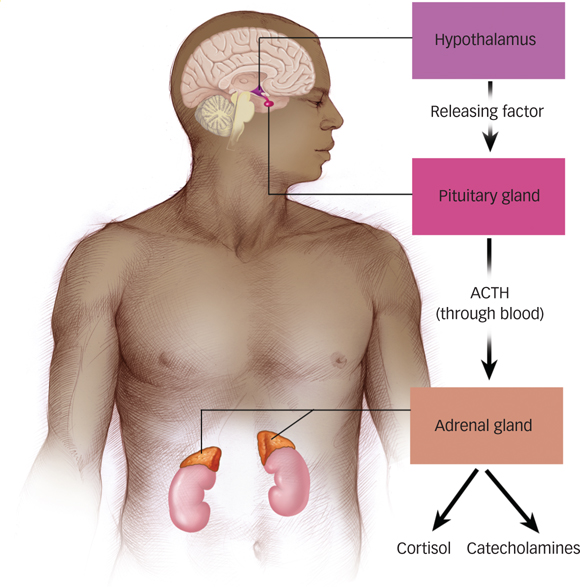

Brain activation in response to threat occurs in the hypothalamus, initiating a cascade of bodily responses that include stimulation of the nearby pituitary gland, which in turn causes stimulation of the adrenal glands (see FIGURE 13.1). This pathway is sometimes called the HPA (hypothalamic–

General Adaptation Syndrome

What are the three phases of GAS?

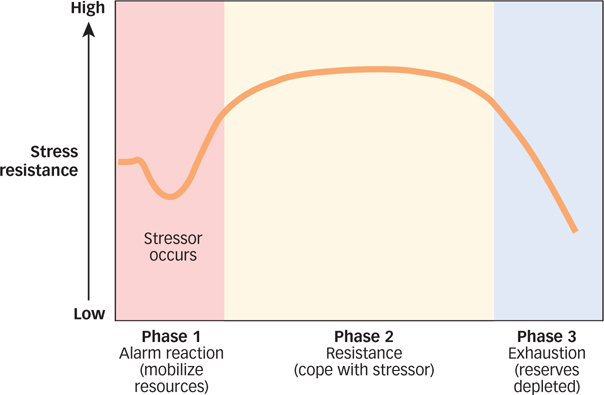

What might have happened if the terrorist attacks of 9/11 were spaced out over a period of days or weeks? In the 1930s, Canadian physician Hans Selye subjected rats to heat, cold, infection, trauma, hemorrhage, and other prolonged stressors, and he found that the stressed-

general adaptation syndrome (GAS)

A three-

417

Stress Effects on Health and Aging

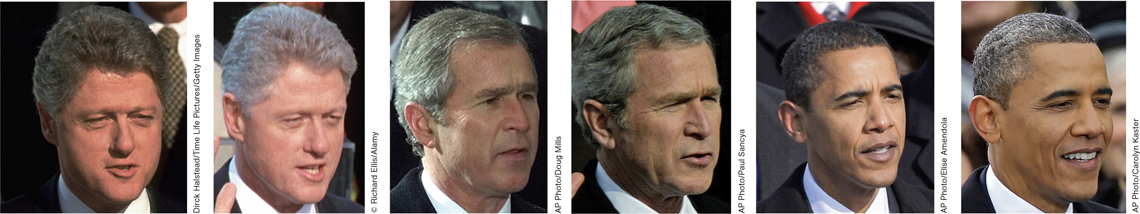

As people age, the body slowly begins to break down (just ask any of the authors of this book). Interestingly, recent research has revealed that stress significantly accelerates the aging process. Elizabeth Smart’s parents noted that, upon being reunited with her after 9 months of separation, they almost did not recognize her because she appeared to have aged so much (Smart, Smart, & Morton, 2003). More generally, people exposed to chronic stress, whether due to their relationships, job, or something else, experience actual wear and tear on their bodies and increased aging. Take a look at the pictures of the past three presidents before and after their terms as president of the United States (arguably, one of the most stressful jobs in the world). As you can see, they appear to have aged much more than the 4–

© Richard Ellis/Alamy

AP Photo/Doug Mills

AP Photo/Paul Sancya

AP Photo/Elise Amendola

AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster

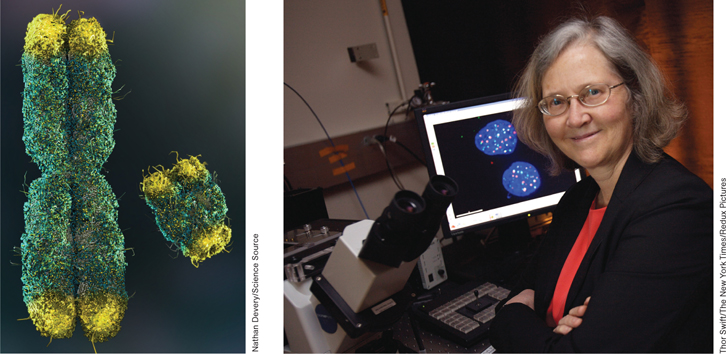

Why does stress increase the aging process? The cells in our bodies are constantly dividing, and as part of this process, our chromosomes are repeatedly copied so that our genetic information is carried into the new cells. This process is facilitated by the presence of telomeres, caps at the ends of each chromosome that protect the ends of chromosomes and prevent them from sticking to each other. They are kind of like the tape at the end of your shoelaces that keeps them from being frayed and not working as efficiently. Each time a cell divides, the telomeres become slightly shorter. Over time, if the telomeres become too short, cells can no longer divide, and this can lead to the development of tumors and a range of diseases. The recent discovery of the function of telomeres and their relation to aging and disease has been one of the most exciting advances in science in the past several decades.

telomeres

Caps at the end of each chromosome that protect the ends of chromosomes and prevent them from sticking to each other.

418

What are telomeres, and what do they do for us?

Interestingly, social stressors can play an important role in this process. People exposed to chronic stress have shorter telomere lengths (Epel et al., 2004). Laboratory studies suggest that increased cortisol can lead to shortened telomeres, which has downstream negative effects in the form of accelerated aging and increased risk of a wide range of diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and depression (Blackburn & Epel, 2012). The good news is that activities like exercise and meditation seem to prevent chronic stress from shortening telomere length, providing a potential explanation of how these activities may convey health benefits such as longer life and lower risk of disease (Epel et al., 2009; Puterman et al., 2010).

Thor Swift/The New York Times/Redux Pictures

Stress Effects on the Immune Response

The immune system is a complex response system that protects the body from bacteria, viruses, and other foreign substances. The immune system is remarkably responsive to psychological influences. Stressors can cause hormones known as glucocorticoids to flood the brain (described in the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter), wearing down the immune system and making it less able to fight invaders (Webster Marketon & Glaser, 2008). For example, in one study, medical student volunteers agreed to receive small wounds to the roof of the mouth. Researchers observed that these wounds healed more slowly during exam periods than during summer vacation (Marucha, Kiecolt-

immune system

A complex response system that protects the body from bacteria, viruses, and other foreign substances.

How does stress affect the immune system?

The effect of stress on immune response may help to explain why social status is related to health. Studies of British civil servants beginning in the 1960s found that mortality varied precisely with civil service grade: the higher the classification, the lower the death rate, regardless of cause (Marmot et al., 1991). One explanation is that people in lower-

419

Stress and Cardiovascular Health

The heart and circulatory system are also sensitive to stress. Chronic stress is a major contributor to coronary heart disease (Krantz & McCeney, 2002), because prolonged stress-

In the 1950s, cardiologists interviewed and tested 3,000 healthy middle-

Type A behavior pattern

The tendency toward easily aroused hostility, impatience, a sense of time urgency, and competitive achievement strivings.

Psychological Reactions

The body’s response to stress is intertwined with responses of the mind. Perhaps the first thing the mind does is try to sort things out—

Stress Interpretation

The interpretation of a stimulus as stressful or not is called primary appraisal (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Primary appraisal allows you to realize that a small dark spot on your shirt is a stressor (spider!) or that a 70-

The next step in interpretation is secondary appraisal, determining whether the stressor is something you can handle or not—

What is the difference between a threat and a challenge?

Burnout

Did you ever take a class from an instructor who had lost interest in the job? The syndrome is easy to spot: The teacher looks distant and blank, almost robotic, giving predictable and humdrum lessons each day, as if it doesn’t matter whether anyone is listening. Now imagine being this instructor. You decided to teach because you wanted to shape young minds. You worked hard, and for a while, things were great. But one day, you looked up to see a room full of miserable students who were bored and didn’t care about anything you had to say. They updated their Facebook pages while you talked and started putting things away long before the end of class. You’re happy at work only when you’re not in class. When people feel this way, especially about their careers, they are suffering from burnout, a state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion created by long-

burnout

A state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion created by long-

420

Burnout is a particular problem in the helping professions (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001). Teachers, nurses, clergy, doctors, dentists, psychologists, social workers, police officers, and others who repeatedly encounter emotional turmoil on the job may only be able to work productively for a limited time before succumbing to burnout (Maslach, 2003). Their unhappiness can even spread to others; people with burnout tend to become disgruntled employees who revel in their co-

Why is burnout a problem especially in the helping professions?

What causes burnout? One theory suggests that the culprit is using your job to give meaning to your life (Pines, 1993). If you define yourself only by your career and gauge your self-

SUMMARY QUIZ [13.2]

Question 13.4

| 1. | The brain activation that occurs in response to a threat begins in the |

- pituitary gland.

- hypothalamus.

- adrenal gland.

- corpus callosum.

b.

Question 13.5

| 2. | According to the general adaptation syndrome, during the _____________ phase, the body adapts to its high state of arousal as it tries to cope with a stressor. |

- exhaustion

- alarm

- resistance

- energy

421

c.

Question 13.6

| 3. | Which of the following statements is most accurate regarding the physiological response to stress? |

- Type A behavior patterns have psychological but not physiological ramifications.

- The link between work-

related stress and coronary heart disease is unfounded. - Stressors can cause hormones to flood the brain, strengthening the immune system.

- The immune system is remarkably responsive to psychological influences.

d.