13.3 Stress Management: Dealing with It

Most college students (92%) say they occasionally feel overwhelmed by the tasks they face, and over a third say they have dropped courses or received low grades in response to severe stress (Duenwald, 2002). No doubt you are among the lucky 8% who are entirely cool and report no stress. But just in case you’re not, you may be interested in stress management techniques.

Mind Management

Stressful events are magnified in the mind. If you fear public speaking, for example, just the thought of an upcoming presentation to a group can create anxiety. And if you do break down during a presentation (going blank, for example, or blurting out something embarrassing), intrusive memories of this stressful event could echo in your mind afterward. A significant part of stress management, then, is control of the mind. Let’s look at three specific strategies.

1. Repressive Coping

Controlling your thoughts is not easy, but some people do seem to be able to banish unpleasant thoughts from the mind. Repressive coping is characterized by avoiding situations or thoughts that are reminders of a stressor and maintaining an artificially positive viewpoint. Everyone has some problems, of course, but repressors are good at deliberately ignoring them (Barnier, Levin, & Maher, 2004). Like Elizabeth Smart, who for years after her rescue focused in interviews on what was happening in her life now rather than repeatedly discussing her past in captivity, people often rearrange their lives in order to avoid stressful situations. It may make sense to try to avoid stressful thoughts and situations if you’re the kind of person who is good at putting unpleasant thoughts and emotions out of mind (Coifman et al., 2007). For some people, however, the avoidance of unpleasant thoughts and situations is so difficult that it can turn into a grim preoccupation (Parker & McNally, 2008; Wegner & Zanakos, 1994).

repressive coping

Avoiding situations or thoughts that are reminders of a stressor and maintaining an artificially positive viewpoint.

When is it useful to avoid stressful thoughts and when is avoidance a problem?

422

2. Rational Coping

Rational coping involves facing the stressor and working to overcome it. This strategy is the opposite of repressive coping and so may seem to be the most unpleasant and unnerving thing you could do when faced with stress. It requires approaching, rather than avoiding, a stressor in order to lessen its longer-

rational coping

Facing the stressor and working to overcome it.

What are the three steps in rational coping?

Rational coping is a three-

3. Reframing

Changing the way you think is another way to cope with stressful thoughts. Reframing involves finding a new or creative way to think about a stressor that reduces its threat. If you experience anxiety at the thought of public speaking, for example, you might reframe by shifting from thinking of an audience as evaluating you to thinking of yourself as evaluating them, and this might make speech giving easier.

reframing

Finding a new or creative way to think about a stressor that reduces its threat.

Reframing can take place spontaneously if people are given the opportunity to spend time thinking and writing about stressful events. In one study, the physical health of college students improved after they spent a few hours writing about their deepest thoughts and feelings. Compared with students who had written about something else, these students were less likely in subsequent months to visit the student health center; they also used less aspirin and achieved better grades (Pennebaker & Chung, 2007). In fact, engaging in such expressive writing was found to improve immune function (Pennebaker, Kiecolt-

How has writing about stressful events been shown to be helpful?

Body Management

Stress can express itself as tension in your neck muscles, as back pain, as a knot in your stomach, as sweaty hands, or as the harried face you glimpse in the mirror. Because stress so often manifests itself through bodily symptoms, body management can reduce stress. Here are four techniques.

1. Meditation

Meditation is the practice of intentional contemplation. Techniques of meditation are associated with a variety of religious traditions and are also practiced outside religious contexts. Some forms of meditation call for attempts to clear the mind of thought, others involve focusing on a single thought (e.g., thinking about a candle flame), and still others involve concentration on breathing or on a mantra (a repetitive sound such as om). At a minimum, the techniques have in common a period of quiet.

meditation

The practice of intentional contemplation.

423

What are some positive outcomes of meditation?

Time spent meditating can be restful and revitalizing. Beyond these immediate benefits, many people also meditate in an effort to experience deeper or transformed consciousness. Whatever the reason, meditation does appear to have positive psychological effects (Hölzel et al., 2011). Many believe it does so, in part, by improving control over attention. Interestingly, experienced meditators show deactivation in the default mode network (which is associated with mind wandering; see Figure 5.5 in the Consciousness chapter) during meditation relative to nonmeditators (Brewer et al., 2011). Even short-

2. Relaxation

Imagine for a moment that you are scratching your chin. Don’t actually do it; just think about it and notice that your body participates by moving ever so slightly, tensing and relaxing in the sequence of the imagined action. Our bodies respond to all the things we think about doing every day. These thoughts create muscle tension even when we think we’re doing nothing at all.

Relaxation therapy is a technique for reducing tension by consciously relaxing muscles of the body. A person in relaxation therapy may be asked to relax specific muscle groups one at a time or to imagine warmth flowing through the body or to think about a relaxing situation. This activity draws on a relaxation response, a condition of reduced muscle tension, cortical activity, heart rate, breathing rate, and blood pressure (Benson, 1990). Basically, as soon as you get in a comfortable position, quiet down, and focus on something repetitive or soothing that holds your attention, you relax.

relaxation therapy

A technique for reducing tension by consciously relaxing muscles of the body.

relaxation response

A condition of reduced muscle tension, cortical activity, heart rate, breathing rate, and blood pressure.

Relaxing on a regular basis can reduce symptoms of stress (Carlson & Hoyle, 1993) and even reduce blood levels of cortisol, the biochemical marker of the stress response (McKinney et al., 1997). For example, in individuals who are suffering from a tension headache, relaxation reduces the tension that causes the headache; in people with cancer, relaxation makes it easier to cope with stressful treatments; in people with stress-

3. Biofeedback

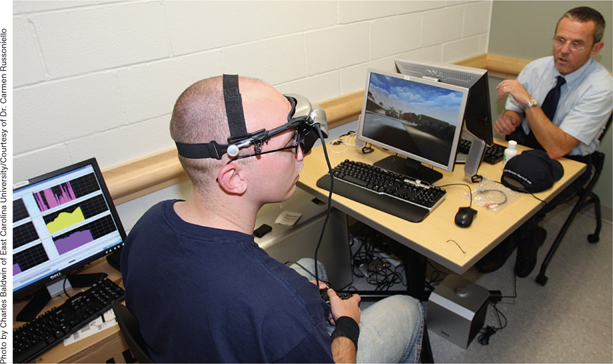

Wouldn’t it be nice if, instead of having to learn to relax, you could just flip a switch and relax as fast as possible? Biofeedback, the use of an external monitoring device to obtain information about a bodily function and possibly gain control over that function, was developed with this goal of high-

biofeedback

The use of an external monitoring device to obtain information about a bodily function and possibly gain control over that function.

How does biofeedback work?

Biofeedback can help people control physiological functions they are not otherwise aware of. For example, you probably have no idea right now what brain-

424

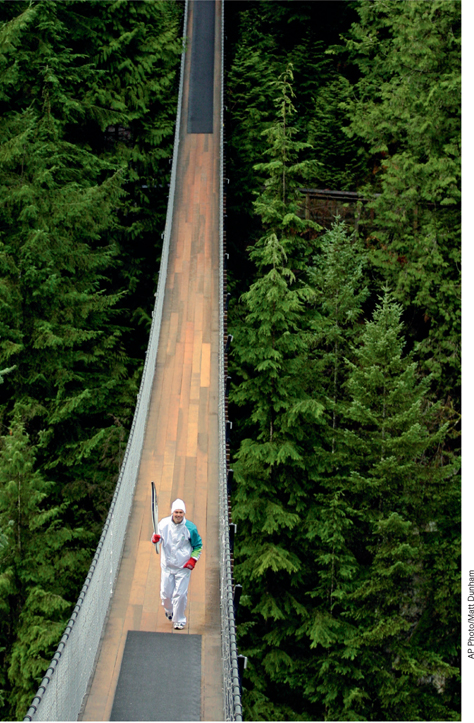

4. Aerobic Exercise

Studies indicate that aerobic exercise (exercise that increases heart rate and oxygen intake for a sustained period) is associated with psychological well-

What are the benefits of exercise?

The reasons for these positive effects are unclear. Researchers have suggested that the effects result from increases in the body’s production of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, which can have a positive effect on mood (as discussed in the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter) or from increases in the production of endorphins (the endogenous opioids discussed in the Neuroscience and Behavior and Consciousness chapters; Jacobs, 1994). Perhaps the simplest thing you can do to improve your happiness and health, then, is to participate regularly in an aerobic activity: Sign up for a dance class, get into a regular basketball game, or start paddling a canoe—

Situation Management

After you have tried to manage stress by managing your mind and managing your body, what’s left to manage? Look around and you’ll notice a whole world out there. Situation management involves changing your life situation as a way of reducing the impact of stress on your mind and body.

1. Social Support

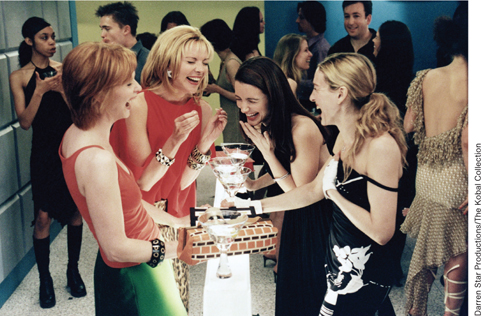

The wisdom of the National Safety Council’s first rule—

social support

The aid gained through interacting with others.

425

Many first-

The value of social support in protecting against stress may be very different for women and men. The fight-

Why is the hormone oxytocin a health advantage for women?

Culture & Community: Land of the free, home of the … stressed?

Land of the free, home of the … stressed? Chances are that you, your parents, grandparents, or someone further back in your family immigrated to the United States. Many families have moved to the United States in pursuit of a better life. Are things immediately better after the move to a new land, or does the process of picking up and moving to a strange land increase stress and lead to negative health consequences?

To answer these questions, researchers used survey data from large representative samples of English-

426

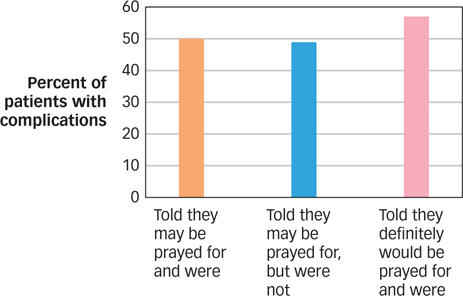

2. Religious Experiences

Polls indicate that over 90% of Americans believe in God, and most who do, pray at least once per day. Although many who believe in a higher power believe that their faith will be rewarded in an afterlife, it turns out that there may be some benefits here on Earth as well. An enormous body of research found associations between religiosity (affiliation with or engagement in the practices of a particular religion), spirituality (having a belief in and engagement with some higher power, not necessarily linked to any particular religion), and positive health outcomes, including lower rates of heart disease, decreases in chronic pain, and improved psychological health (Seybold & Hill, 2001).

Why are religiosity and spirituality associated with health benefits?

Why do people who endorse religiosity or spirituality have better mental and physical health? Engagement in religious/spiritual practices, such as attendance at weekly religious services, may lead to the development of a stronger and more extensive social network, which has well-

3. Humor

Wouldn’t it be nice to laugh at your troubles and move on? Most of us recognize that humor can diffuse unpleasant situations and reduce stress. Is laughter truly the best medicine? Should we close down the hospitals and send in the clowns?

There is a kernel of truth to the theory that humor can help us cope with stress. For example, humor can reduce sensitivity to pain and distress. In one study, participants were more tolerant of the pain from an over-

Humor can also reduce the time needed to calm down after a stressful event. For example, men viewing a highly stressful film about three industrial accidents were asked to narrate the film aloud, either by describing the events seriously or by making their commentary as funny as possible. Although men in both groups reported feeling tense while watching the film and showed increased levels of sympathetic nervous arousal (increased heart rate and skin conductance, decreased skin temperature), those looking for humor in the experience bounced back to normal arousal levels more quickly than did those in the serious story group (Newman & Stone, 1996).

427

How does humor mitigate stress?

SUMMARY QUIZ [13.3]

Question 13.7

| 1. | Meditation is an altered state of consciousness that occurs |

- with the aid of drugs.

- through hypnosis.

- naturally or through special practices.

- as a result of dreamlike brain activity.

c.

Question 13.8

| 2. | Finding a new or creative way to think about a stressor that reduces its threat is called |

- stress inoculation.

- repressive coping.

- reframing.

- rational coping.

c.

Question 13.9

| 3. | The positive health outcomes associated with religiosity and spirituality are believed to be the result of all of the following except |

- enhanced social support.

- engagement in healthier behavior.

- endorsement of hope and optimism.

- intercessory prayer.

d.