13.5 The Psychology of Health: Feeling Good

Two kinds of psychological factors influence personal health: health-

Personality and Health

Different health problems seem to plague different social groups. For example, men are more susceptible to heart disease than are women, and African Americans are more susceptible to asthma than are Asian or European Americans. Beyond these general social categories, personality turns out to be a factor in wellness, with individual differences in optimism and hardiness important influences.

Optimism

An optimist who believes that “in uncertain times, I usually expect the best” is likely to be healthier than a pessimist who believes that “if something can go wrong for me, it will.” One recent review of dozens of studies including tens of thousands of participants concluded that of all of the measures of psychological well-

Rather than improving physical health directly, optimism seems to aid in the maintenance of psychological health in the face of physical health problems. When sick, optimists are more likely than pessimists to maintain positive emotions, avoid negative emotions such as anxiety and depression, stick to medical regimens their caregivers have prescribed, and keep up their relationships with others. Optimism also seems to aid in the maintenance of physical health. For instance, optimism appears to be associated with cardiovascular health because optimistic people tend to engage in healthier behaviors like eating a balanced diet and exercising, which in turn decrease the risk of heart disease (Boehm et al., 2013). So being optimistic is a positive asset, but it takes more than just hope to obtain positive health benefits.

432

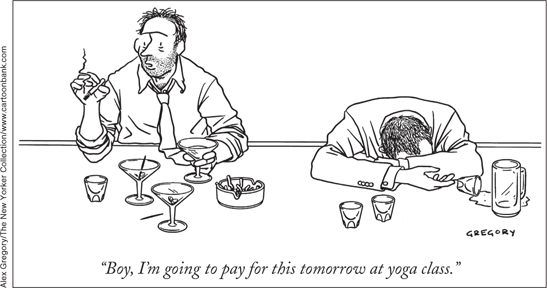

Who’s healthier, the optimist or the pessimist? Why?

The benefits of optimism raise an important question: If the traits of optimism and pessimism are stable over time—

Hardiness

Some people seem to be thick-

Can anyone develop hardiness? In one study, participants attended 10 weekly hardiness-

Health-Promoting Behaviors and Self-Regulation

Even without changing our personalities at all, we can do certain things to be healthy. The importance of healthy eating, safe sex, and giving up smoking are common knowledge. But we don’t seem to be acting on the basis of this knowledge. At the turn of the 21st century, 69% of Americans over 20 are overweight or obese (National Center for Health Statistics, 2012). The prevalence of unsafe sex is difficult to estimate, but 20 million Americans contract one or more new sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) each year (Satterwhite et al., 2013). And despite endless warnings, 21% of Americans still smoke cigarettes (Pleis, Lucas, & Ward, 2009). What’s going on?

433

Self-Regulation

Doing what is good for you is not necessarily easy. Engaging in health-

self-regulation

The exercise of voluntary control over the self to bring the self into line with preferred standards.

Why is it difficult to achieve and maintain self-

One theory suggests that self-

Eating Wisely

In many Western cultures, the weight of the average citizen is increasing alarmingly. One explanation is based on our evolutionary history: In order to ensure their survival, our ancestors found it useful to eat well in times of plenty in order to store calories for leaner times. In postindustrial societies in the 21st century, however, there are no leaner times, and people can’t burn all of the calories they consume (Pinel, Assanand, & Lehman, 2000). But why, then, are people in France leaner on average than Americans even though their foods are high in fat? One reason has to do with the fact that activity level in France is greater. Another is that portion sizes in France are significantly smaller than in the United States, but at the same time, people in France take longer to finish their smaller meals. Right now, Americans seem to be involved in some kind of national eating contest, whereas in France, people are eating less food more slowly, perhaps leading them to be more conscious of what they are eating. This, ironically, probably leads to lower French fry consumption.

DATA VISUALIZATION

The Relationship Between Stress and Eating Habits www.macmillanhighered.com/

Why is exercise a more effective weight-

Short of moving to France, what can you do? Studies indicate that dieting doesn’t always work because the process of conscious self-

434

Avoiding Sexual Risks

People put themselves at risk when they have unprotected vaginal, oral, or anal intercourse. Sexually active adolescents and adults are usually aware of such risks, not to mention the risk of unwanted pregnancy, and yet many behave in risky ways nonetheless. Why doesn’t awareness translate into avoidance? Risk takers harbor an illusion of unique invulnerability, a systematic bias toward believing that they are less likely to fall victim to the problem than are others (Perloff & Fetzer, 1986). For example, a study of sexually active female college students found that respondents judged their own likelihood of getting pregnant in the next year as less than 10%, but they estimated the average for other women at the university to be 27% (Burger & Burns, 1988).

Why does planning ahead reduce sexual risk taking?

Unprotected sex often is the impulsive result of last-

Not Smoking

To quit smoking forever, how many times do you need to quit?

One in two smokers dies prematurely from smoking-

Nicotine, the active ingredient in cigarettes, is addictive, so smoking is difficult to stop once the habit is established (discussed in the Consciousness chapter). As in other forms of self-

Psychological programs and techniques to help people kick the habit include nicotine replacement systems such as gum and skin patches, counseling programs, and hypnosis, but these programs are not always successful. Trying again and again in different ways is apparently the best approach (Schachter, 1982). After all, to quit smoking forever, you only need to quit one more time than you start up. But like the self-

435

Other Voices: Freedom to Be Unhealthy?

Freedom to Be Unhealthy?

In the chapter on Emotion and Motivation, you learned about the health benefits and risks associated with what you eat. In this chapter, you learned that what you do (Do you exercise?) and what you think (Are you an optimist?) also can influence your experience of stress and health. The research is clear that people who eat right and exercise regularly have better mental and physical health outcomes. Is it our business, then, to try to get people to eat better and exercise more?

The former mayor of New York City, Michael Bloomberg, recently advocated for a tax on large, sugary drinks, which has been nicknamed the “soda tax.” Some have praised this idea, believing that it is our responsibility to structure society in a way that improves the health of our citizens—

On narrow technical grounds, a New York State court rejected Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg’s proposed curbs on large sodas and other sugary drinks. The ruling is being appealed, but many people who viewed the proposal as a step down a slippery slope to a nanny state were quick to celebrate the court’s move. Beyond questioning the mayor’s legal authority to impose a 16-

But while almost everyone celebrates freedom in the abstract, defending one cherished freedom often requires sacrificing another. Whatever the flaws in Mr. Bloomberg’s proposal, it sprang from an entirely commendable concern: a desire to protect parents’ freedom to raise healthy children.

Being free to do something doesn’t just mean being legally permitted to do it. It also means having a reasonable prospect of being able to do it. Parents don’t want their children to become obese, or to suffer the grave consequences of diet-

The mayor’s critics want to protect their own freedom to consume soft drinks in 32-

Does frequent exposure to supersize sodas really limit parents’ freedom to raise healthy children? There’s room for skepticism, because people often believe that they’re not much influenced by others’ opinions and behavior. But believing doesn’t make it so.

As an Illinois state legislator in 1842, Abraham Lincoln deftly illustrated the absurdity of this particular conceit: “Let me ask the man who could maintain this position most stiffly, what compensation he will accept to go to church some Sunday and sit during the sermon with his wife’s bonnet upon his head?” Most men, Lincoln conjectured, would demand a considerable sum—

Even those who concede the obvious power of the social environment have little reason to worry about how their own choices might alter it. Collectively, however, our choices can profoundly transform the environment, often in ways that cause serious problems. And that makes the social environment an object of legitimate public concern.

Imagine a society like the United States before 1964, where unregulated individual choices produced high percentages of smokers in the population—

Smokers harm not only themselves and those who inhale secondhand smoke but also those who simply want their children to grow up to be nonsmokers. People can urge their children to ignore peer influences, of course, but that’s often a losing battle.

No rational deliberation about smoking policies can ignore the fact that smoking harms others in this way. Such considerations helped give rise to a variety of policies that discourage smoking. In New York City, for example, smoking is no longer permitted in many public places, and state and city taxes on a pack of cigarettes are now near $6.

Such policies have reduced the national smoking rate by more than half since 1965, making it much easier for parents to raise their children to be nonsmokers. That’s an enormous benefit. Opponents of smoking restrictions must be prepared to show that those adversely affected by them suffer harm that outweighs that benefit. Given that the overwhelming majority of smokers themselves regret having taken up the habit, that’s a tall order.

Parallel arguments apply to sugary drinks. Unless we’re prepared to deny, against all evidence, that the environment powerfully influences children’s choices, we’re forced to conclude that rejecting Mr. Bloomberg’s proposal significantly curtails parents’ freedom to achieve the perfectly reasonable goal of raising healthy children. Why should opponents of the mayor’s proposal be permitted to limit parents’ freedom in this way, merely to spare themselves the trivial inconvenience of having to order a second 16-

Fortunately, society’s legitimate interest in the social environment needn’t be expressed by means of invasive prohibitions. The public policy goal that prompted the mayor’s proposal could also be served in more direct and less intrusive ways.

For example, we could tax sugary soft drinks. In 2010, the mayor himself praised a proposal for a penny-

The case for reintroducing such a proposal is strong. We have to tax something, after all, and taxing soft drinks would let us reduce taxes now imposed on manifestly useful activities. At the federal level, for example, a tax on soda would permit a reduction in the payroll tax, which would encourage businesses to hire more workers.

436

Just as few smokers are glad that they smoke, few people go to their graves wishing that they and their loved ones had drunk more sugary soft drinks. Evidence suggests that the current high volume of soft-

Where do you stand? The research described in this textbook makes clear that healthier eating and behavior lead to better health outcomes—

From the New York Times, March 23, 2013 © 2013 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited. http:/

SUMMARY QUIZ [13.5]

Question 13.13

| 1. | When sick, optimists are more likely than pessimists to |

- maintain positive emotions.

- become depressed.

- ignore their caregiver’s advice.

- avoid contact with others.

a.

Question 13.14

| 2. | Which of the following is NOT a trait associated with hardiness? |

- a sense of commitment

- an aversion to criticism

- a belief in control

- a willingness to accept challenge

b.

Question 13.15

| 3. | Stress _____________ the self- |

- strengthens

- has no effect on

- disrupts

- normalizes

c.