14.1 Defining Mental Disorders: What Is Abnormal?

The concept of a mental disorder seems simple at first glance, but it turns out to be very complex and quite tricky (similar to clearly defining “consciousness,” “stress,” or “personality”). Any extreme variation in your thoughts, feelings, or behaviors is not a mental disorder. For instance, severe anxiety before a test, sadness after the loss of a loved one, or a night of excessive alcohol consumption are not necessarily pathological. Similarly, a persistent pattern of deviating from the norm does not necessarily qualify a person for the diagnosis of a mental disorder. If it did, we would diagnose mental disorders in the most creative and visionary people—

So what is a mental disorder? Perhaps surprisingly, there is no universal agreement on a precise definition of the term “mental disorder.” However, there is general agreement that a mental disorder can be defined as a persistent disturbance or dysfunction in behavior, thoughts, or emotions that causes significant distress or impairment (Stein et al., 2010; Wakefield, 2007). One way to think about mental disorders is as dysfunctions or deficits in the normal human psychological processes you have learned about throughout this book. People with mental disorders have problems with their perception, memory, learning, emotion, motivation, thinking, and social processes. You might ask: But this is still a broad definition, so what kinds of disturbances “count” as mental disorders? How long must they last to be considered “persistent?” And how much distress or impairment is required? These are all hotly debated questions in the field.

mental disorder

A persistent disturbance or dysfunction in behavior, thoughts, or emotions that causes significant distress or impairment.

Conceptualizing Mental Disorders

Since ancient times, there have been reports of people acting strangely or reporting bizarre thoughts or emotions. Until fairly recently, such difficulties were interpreted as possession by spirits or demons, as enchantment by a witch or shaman, or as God’s punishment for wrongdoing. In many societies, including our own, people with psychological disorders have been feared and ridiculed, and often they were treated as criminals who were punished, imprisoned, or put to death for their “crime” of deviating from the normal.

441

Over the past 200 years, these ways of looking at psychological abnormalities have largely been replaced in most parts of the world by a medical model, in which abnormal psychological experiences are conceptualized as illnesses that, like physical illnesses, have biological and environmental causes, defined symptoms, and possible cures. Conceptualizing abnormal thoughts and behaviors as illness suggests that a first step is to determine the nature of the problem through diagnosis.

medical model

Abnormal psychological experiences are conceptualized as illnesses that, like physical illnesses, have biological and environmental causes, defined symptoms, and possible cures.

What’s the first step in helping someone with a psychological disorder?

In diagnosis, clinicians seek to determine the nature of a person’s mental disorder by assessing signs (objectively observed indicators of a disorder) and symptoms (subjectively reported behaviors, thoughts, and emotions) that suggest an underlying illness. So, for example, just as self-

- A disorder refers to a common set of signs and symptoms.

- A disease is a known pathological process affecting the body.

- A diagnosis is a determination as to whether a disorder or disease is present (Kraemer, Shrout, & Rubio-

Stipec, 2007).

Importantly, knowing that a disorder is present (i.e., diagnosed) does not necessarily mean that we know the underlying disease process in the body that gives rise to the signs and symptoms of the disorder.

Viewing mental disorders as medical problems reminds us that people who are suffering deserve care and treatment, not condemnation. Nevertheless, there are some criticisms of the medical model. Some psychologists argue that it is inappropriate to use clients’ subjective self-

442

Classifying Disorders: The DSM

So how is the medical model used to classify the wide range of abnormal behaviors that occur among humans? Most people working in the area of mental disorders use a standardized system for classifying mental disorders called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), a classification system that describes the features used to diagnose each recognized mental disorder and indicates how the disorder can be distinguished from other, similar problems. Each disorder is named and classified as a distinct illness. The initial version of the DSM, published in 1952, provided a common language for talking about disorders. This was a major advance in the study of mental disorders; however, the diagnostic criteria listed in these early volumes were quite vague.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)

A classification system that describes the features used to diagnose each recognized mental disorder and indicates how the disorder can be distinguished from other, similar problems.

Over the decades, revised editions of the DSM have moved from vague descriptions of disorders to very detailed lists of symptoms (or diagnostic criteria) that had to be present in order for a disorder to be diagnosed. For instance, in addition to being extremely sad or depressed (for at least 2 weeks), a person must have at least five of nine agreed-

In May 2013, the American Psychiatric Association released the newest, fifth edition of the DSM, the DSM–

|

|

Source: Information from American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

DATA VISUALIZATION

Comorbidity: the Relationship Between Related Disorders

How has the DSM changed over time?

Studies of large, representative samples of the U.S. population reveal that approximately half of Americans report experiencing at least one mental disorder during the course of their lives (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005). And, most of those with a mental disorder (greater than 80%) report comorbidity, which refers to the co-

comorbidity

The co-

Causation of Disorders

The medical model of mental disorder suggests that knowing a person’s diagnosis is useful because any given category of mental illness is likely to have a distinctive cause. In other words, just as different viruses, bacteria, or genetic abnormalities cause different physical illnesses, so a specifiable pattern of causes (or etiology) may exist for different psychological disorders. The medical model also suggests that each category of mental disorder is likely to have a common prognosis, a typical course over time and susceptibility to treatment and cure. Unfortunately, this basic medical model is usually an oversimplification; it is rarely useful to focus on a single cause that is internal to the person and that suggests a single cure.

443

444

Instead, most psychologists take an integrated biopsychosocial perspective that explains mental disorders as the result of interactions among biological, psychological, and social factors. On the biological side, the focus is on genetic and epigenetic influences, biochemical imbalances, and abnormalities in brain structure and function. The psychological perspective focuses on maladaptive learning and coping, cognitive biases, dysfunctional attitudes, and interpersonal problems. Social factors include poor socialization, stressful life experiences, and cultural and social inequities. The complexity of causation suggests that different individuals can experience a similar mental disorder (e.g., depression) for different reasons. A person might fall into depression as a result of biological causes (e.g., genetics, hormones), psychological causes (e.g., faulty beliefs, hopelessness, poor strategies for coping with loss), environmental causes (e.g., stress or loneliness), or more likely as a result of some combination of these factors. And, of course, multiple causes mean there may not be a single cure.

biopsychosocial perspective

Explains mental disorders as the result of interactions among biological, psychological, and social factors.

Why does assessment require looking at a number of factors?

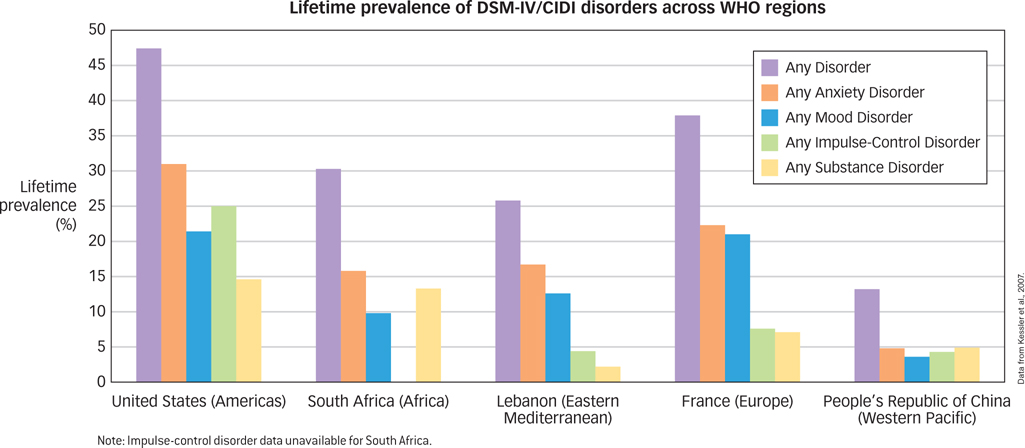

Culture & Community: What do mental disorders look like in different parts of the world?

What do mental disorders look like in different parts of the world? Are the mental disorders that we see in the United States also experienced by people in other parts of the world? In an effort to find out, Ronald Kessler and colleagues launched the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys, a large-

Although all countries appear to have the common mental disorders described above, it is clear that cultural context can influence how mental disorders are experienced, described, assessed, and treated. To address this issue, the DSM–

445

The observation that most disorders have both internal (biological and psychological) and external (environmental) causes has given rise to a theory known as the diathesis-stress model, which suggests that a person may be predisposed for a psychological disorder that remains unexpressed until triggered by stress. The diathesis is the internal predisposition, and the stress is the external trigger. For example, most people were able to cope with their strong emotional reactions to the terrorist attack of September 11, 2001. However, for some who had a predisposition to negative emotions, the horror of the events may have overwhelmed the person’s ability to cope, thereby precipitating a psychological disorder. Although diatheses can be inherited, it’s important to remember that heritability is not destiny. A person who inherits a diathesis may never encounter the precipitating stress, whereas someone with little genetic propensity to a disorder may still come to suffer from such a disorder given the right pattern of stress.

diathesis–stress model

Suggests that a person may be predisposed for a psychological disorder that remains unexpressed until triggered by stress.

A New Approach to Understanding Mental Disorders: RDoC

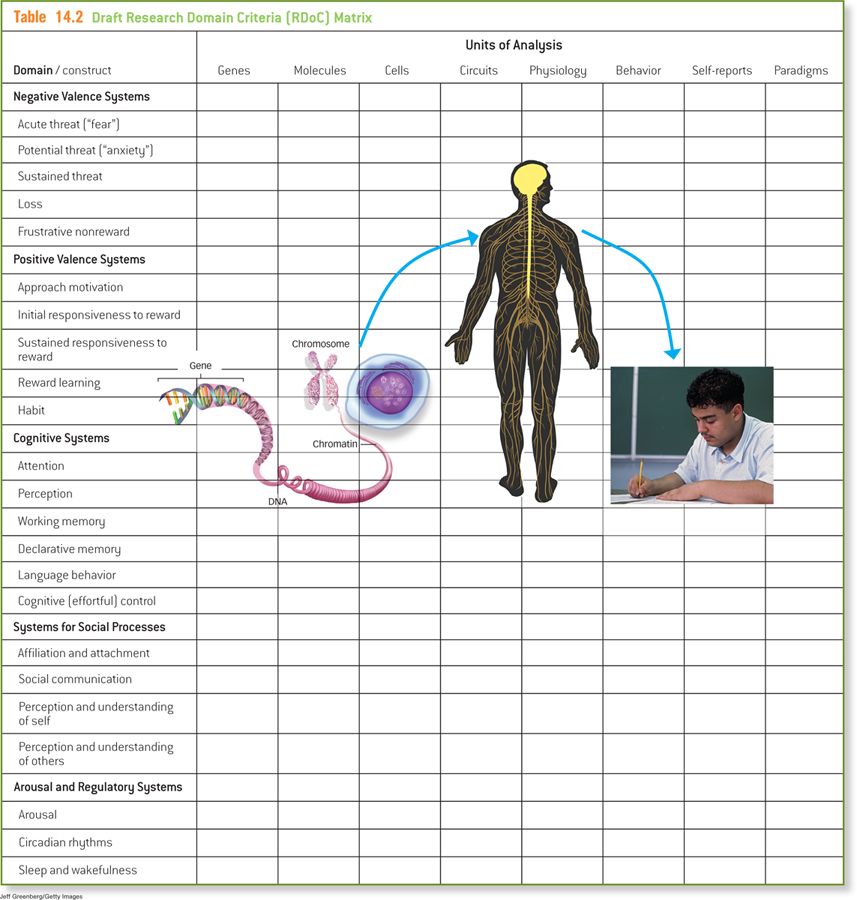

Although the DSM provides a useful framework for classifying disorders, there has been a growing concern that the findings from scientific research on the factors that cause psychopathology do not map neatly onto individual DSM diagnoses. In order to better understand what actually causes mental disorders, researchers at the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) have proposed a new framework for thinking about mental disorders, one that is focused not on the currently defined DSM categories of disorders, but on the basic biological, cognitive, and behavioral processes (or “constructs”) that are believed to be the building blocks of mental disorders. This new system is called the Research Domain Criteria Project (RDoC), a new initiative that aims to guide the classification and understanding of mental disorders by revealing the basic processes that give rise to them. The RDoC is intended not to immediately replace the DSM but to inform future revisions to it in the coming years. Using the RDoC, researchers focus on biological domains, such as arousal and sleep patterns; and psychological domains, such as learning, attention, and memory; and social domains, such as attachment and self-

Research Domain Criteria Project (RDoC)

A new initiative that aims to guide the classification and understanding of mental disorders by revealing the basic processes that give rise to them.

Through the RDoC approach, the NIMH would like to shift researchers away from studying currently defined DSM categories and toward the study of the dimensional biopsychosocial processes believed, at the extreme end of the continuum, to lead to mental disorders. The long-

446

447

You might notice that the list of domains in Table 14.2 looks like a slightly more detailed version of the table of contents for this book! The RDoC approach has an overall emphasis on neuroscience (Chapter 3), with specific focuses on abnormalities in emotional and motivational systems (Chapter 8), cognitive systems such as memory (Chapter 6), learning (Chapter 7), language and cognition (Chapter 9), social processes (Chapter 12), and stress and arousal (Chapter 13). From the RDoC perspective, mental disorders can be thought of as the result of abnormalities or dysfunctions in normal psychological processes. By learning about many of these processes in this book, you will likely have a good understanding of new definitions of mental disorders as they are developed in the years ahead.

Dangers of Labeling

An important complication in the diagnosis and classification of psychological disorders is the effect of labeling. Psychiatric labels can have negative consequences because many labels carry the baggage of negative stereotypes and stigma, such as the idea that mental disorder is a sign of personal weakness or the idea that psychiatric patients are dangerous. The stigma associated with mental disorders may explain why most people with diagnosable psychological disorders (approximately 60%) do not seek treatment (Kessler, Demler, et al., 2005; Wang, Berglund, et al., 2005).

Why might someone avoid seeking help?

Unfortunately, educating people about mental disorders does not dispel the stigma borne by those with these conditions (Phelan et al., 1997). In fact, expectations created by psychiatric labels can sometimes even compromise the judgment of mental health professionals (Garb, 1998; Langer & Abelson, 1974; Temerlin & Trousdale, 1969). In a classic demonstration of this phenomenon, researchers reported to different mental hospitals complaining of “hearing voices,” a symptom sometimes found in people with schizophrenia. Each was admitted to a hospital, and each promptly reported that the symptom had ceased. Even so, hospital staff were reluctant to identify these people as normal: It took an average of 19 days for these “patients” to secure their release, and even then they were released with the diagnosis of “schizophrenia in remission” (Rosenhan, 1973). Apparently, once hospital staff had labeled these patients as having a psychological disease, the label stuck.

Labeling may even affect how labeled individuals view themselves; persons given such a label may come to view themselves not just as mentally disordered, but as hopeless or worthless. Such a view may cause them to develop an attitude of defeat and, as a result, to fail to work toward their own recovery. As one small step toward counteracting such consequences, clinicians have adopted the important practice of applying labels to the disorder and not to the person with the disorder. For example, an individual might be described as “a person with schizophrenia,” not as “a schizophrenic.” You’ll notice that we follow this convention in the text.

SUMMARY QUIZ [14.1]

Question 14.1

| 1. | The conception of psychological disorders as diseases that have symptoms and possible cures is referred to as |

- the medical model.

- physiognomy.

- the root syndrome framework.

- a diagnostic system.

a.

448

Question 14.2

| 2. | The DSM– |

- medical model.

- classification system.

- set of theoretical assumptions.

- collection of physiological definitions.

b.

Question 14.3

| 3. | Comorbidity of disorders refers to |

- symptoms stemming from internal dysfunction.

- the relative risk of death arising from a disorder.

- the co-

occurrence of two or more disorders in a single individual. - the existence of disorders on a continuum from normal to abnormal.

c.

Question 14.4

| 4. | The RDoC aims to |

- provide evidence for the disorders currently listed in the DSM-

5 . - shift researchers from focusing on a symptom-

based classification of mental disorders to a focus on underlying processes that may lead to mental disorders. - prevent the negative consequences of labeling individuals with mental disorders.

- help researchers better describe the observed symptoms of mental disorders.

b.