14.5 Depressive and Bipolar Disorders: At the Mercy of Emotions

You’re probably in a mood right now. Maybe you’re happy that it’s almost time to get a snack or saddened by something you heard from a friend. As you learned in the Emotion and Motivation chapter, moods are relatively long-

mood disorders

Mental disorders that have mood disturbance as their predominant feature.

Depressive Disorders

Mark, a 34-

Major depressive disorder (or unipolar depression), which we refer to here simply as “depression,” is a disorder characterized by a severely depressed mood and/or inability to experience pleasure that lasts 2 or more weeks and is accompanied by feelings of worthlessness, lethargy, and sleep and appetite disturbance. Some people experience recurrent depressive episodes in a seasonal pattern, commonly known as seasonal affective disorder (SAD). In most cases, the episodes begin in fall or winter and remit in spring, and this pattern is due to reduced levels of light over the colder seasons (Westrin & Lam, 2007). Nevertheless, recurrent summer depressive episodes have been reported. A winter-

major depressive disorder (or unipolar depression)

A disorder characterized by a severely depressed mood and/or inability to experience pleasure that lasts 2 or more weeks and is accompanied by feelings of worthlessness, lethargy, and sleep and appetite disturbance.

seasonal affective disorder (SAD)

Recurrent depressive episodes in a seasonal pattern.

What is the difference between depression and sadness?

Approximately 18% of people in the United States meet criteria for depression at some point in their lives (Kessler et al., 2012). On average, major depression lasts about 12 weeks (Eaton et al., 2008). However, without treatment, approximately 80% of individuals will experience at least one recurrence of the disorder (Judd, 1997; Mueller et al., 1999).

456

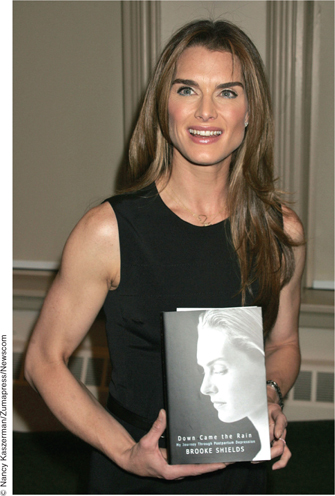

Much like the anxiety disorders, the rate of depression is much higher in women (22%) than in men (14%; Kessler et al., 2012). Socioeconomic standing has been invoked as an explanation for women’s heightened risk: Their incomes are lower than those of men, and poverty could cause depression. Sex differences in hormones are another possibility: Estrogen, androgen, and progesterone influence depression; some women experience postpartum depression (depression following childbirth) due to changing hormone balances. It is also possible that the higher rate of depression in women reflects greater willingness by women to face their depression and seek out help, leading to higher rates of diagnosis (Nolen-

Biological Factors

Beginning in the 1950s, researchers noticed that drugs that increased levels of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and serotonin could sometimes reduce depression. This observation suggested that depression might be caused by depletion of these neurotransmitters (Schildkraut, 1965), leading to the development and widespread use of such prescription drugs as Prozac and Zoloft, which increase the availability of serotonin in the brain. Further research has shown, however, that reduced levels of these neurotransmitters cannot be the whole story regarding the causes of depression. For example, some studies have found increases in norepinephrine activity among depressed individuals (Thase & Howland, 1995). Moreover, even though the antidepressant medications change neurochemical transmission in less than a day, they typically take at least 2 weeks to relieve depressive symptoms and are not effective in decreasing depressive symptoms in many cases. A biochemical model of depression has yet to be developed that accounts for all the evidence.

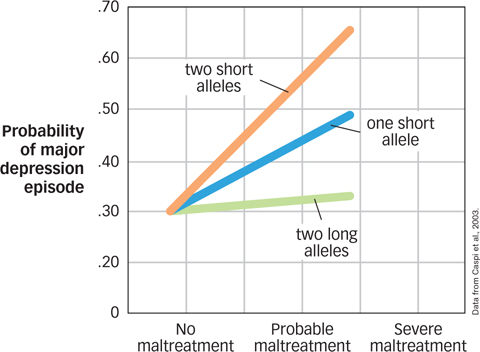

Newer biological models of depression have tried to explain depression using a diathesis-

Psychological Factors

If optimists see the world through rose-

Elaborating on this initial idea, researchers proposed a theory of depression that emphasizes the role of people’s negative inferences about the causes of their experiences (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978). Helplessness theory, which is a part of the cognitive model of depression, is the idea that individuals who are prone to depression automatically attribute negative experiences to causes that are internal (i.e., their own fault), stable (i.e., unlikely to change), and global (i.e., widespread). For example, a student at risk for depression might view a bad grade on a math test as a sign of low intelligence (internal) that will never change (stable) and that will lead to failure in all his or her future endeavors (global). In contrast, a student without this tendency might have the opposite response, attributing the grade to something external (poor teaching), unstable (a missed study session), and/or specific (boring subject).

helplessness theory

The idea that individuals who are prone to depression automatically attribute negative experiences to causes that are internal (i.e., their own fault), stable (i.e., unlikely to change), and global (i.e., widespread).

457

What is helplessness theory?

More recent research suggests that people with depression may have biases to interpret information negatively, coupled with better recall of negative information and trouble turning their attention away from negative information (Gotlib & Joormann, 2010). For example, a student at risk for depression who got a bad grade on a test might interpret a well-

Bipolar Disorder

Julie, a 20-

In addition to her manic episodes, Julie (like Woolf) had a history of depression. The diagnostic label for this constellation of symptoms is bipolar disorder, a condition characterized by cycles of abnormal, persistent high mood (mania) and low mood (depression). The depressive phase of bipolar disorder is often clinically indistinguishable from major depression (Johnson, Cuellar, & Miller, 2009). In the manic phase, which must last at least 1 week to meet DSM requirements, mood can be elevated, expansive, or irritable. Other prominent symptoms include grandiosity, decreased need for sleep, talkativeness, racing thoughts, distractibility, and reckless behavior (such as compulsive gambling, sexual indiscretions, and unrestrained spending sprees). Psychotic features such as hallucinations (erroneous perceptions) and delusions (erroneous beliefs) may be present, so the disorder can be misdiagnosed as schizophrenia (described in a later section).

bipolar disorder

A condition characterized by cycles of abnormal, persistent high mood (mania) and low mood (depression).

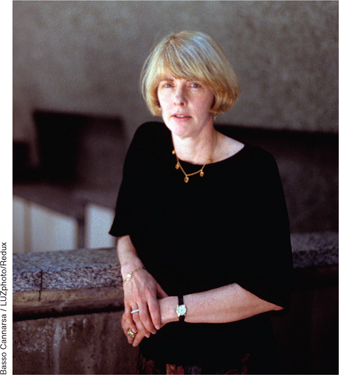

Here’s how Kay Redfield Jamison (1995, p. 67) described her own experience with bipolar disorder in An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness.

There is a particular kind of pain, elation, loneliness, and terror involved in this kind of madness. When you’re high it’s tremendous. The ideas and feelings are fast and frequent like shooting stars, and you follow them until you find better and brighter ones …. But, somewhere, this changes. The fast ideas are far too fast, and there are far too many; overwhelming confusion replaces clarity. Memory goes. Humor and absorption on friends’ faces are replaced by fear and concern. Everything previously moving with the grain is now against—

458

The lifetime risk for bipolar disorder is about 2.5% and does not differ between men and women (Kessler et al., 2012). Bipolar disorder is typically a recurrent condition, with approximately 90% of afflicted people suffering from several episodes over a lifetime (Coryell et al., 1995). About 10% of people with bipolar disorder have rapid cycling bipolar disorder, characterized by at least four mood episodes (either manic or depressive) every year, and this form of the disorder is particularly difficult to treat (Post et al., 2008). Rapid cycling is more common in women than in men and is sometimes precipitated by taking certain kinds of antidepressant drugs (Liebenluft, 1996; Whybrow, 1997). Unfortunately, bipolar disorder tends to be persistent. In one study, 24% of the participants had relapsed within 6 months of recovery from an episode, and 77% had at least one new episode within 4 years of recovery (Coryell et al., 1995).

Some have suggested that people with psychotic and mood (especially bipolar) disorders have higher creativity and intellectual ability (Andreasen, 2011). In bipolar disorder, the suggestion goes, before the mania becomes too pronounced, the energy, grandiosity, and ambition that it supplies may help people achieve great things. In addition to Virginia Woolf, notable individuals thought to have had the disorder include Isaac Newton, Vincent Van Gogh, Abraham Lincoln, Ernest Hemingway, Winston Churchill, and Theodore Roosevelt.

Biological Factors

Like most other mental disorders, bipolar disorder is most likely polygenic, arising from the interaction of multiple genes that combine to create the symptoms observed in those with this disorder; however, these genes have been difficult to identify. Adding to the complexity, there also is evidence that common genetic risk factors are associated with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, as well as with major depression, autism spectrum disorder, and attention-

What findings offer exciting new evidence of why symptoms of different disorders seem to overlap?

There is growing evidence that the epigenetic changes you learned about in the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter can help to explain how genetic risk factors influence the development of bipolar and related disorders. Remember how rat pups whose moms spent less time licking and grooming them experienced epigenetic changes that led to a poorer stress response? These same kinds of epigenetic effects seem to occur in humans who develop symptoms of mental disorders. For instance, studies examining monozygotic twin pairs (identical twins who share 100% of their DNA) in which one develops bipolar disorder or schizophrenia and one doesn’t, reveal significant epigenetic differences between the two, particularly at genetic locations known to be important in brain development and the occurrence of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (Dempster et al., 2011; Labrie, Pai, & Petronis, 2012).

459

Psychological Factors

How does stress relate to manic-

Stressful life experiences often precede manic and depressive episodes (Johnson, Cuellar, et al., 2008). One study found that severely stressed individuals took an average of three times longer to recover from an episode than did individuals not affected by stress (Johnson & Miller, 1997). Personality characteristics such as neuroticism and conscientiousness have also been found to predict increases in bipolar symptoms over time (Lozano & Johnson, 2001). Finally, people living with family members high on expressed emotion, which in this context is a measure of how much hostility, criticism, and emotional overinvolvement are used when speaking about a family member with a mental disorder, are more likely to relapse than people with supportive families (Miklowitz & Johnson, 2006). This is true not just of those with bipolar disorder: Expressed emotion is associated with higher rates of relapse across a wide range of mental disorders (Hooley, 2007).

expressed emotion

A measure of how much hostility, criticism, and emotional overinvolvement are used when speaking about a family member with a mental disorder.

SUMMARY QUIZ [14.5]

Question 14.10

| 1. | Major depression is characterized by a severely depressed mood that lasts at least |

- 2 weeks.

- 1 week.

- 1 month.

- 6 months.

a.

Question 14.11

| 2. | Extreme mood swings between _______ characterize bipolar disorder. |

- depression and mania

- stress and lethargy

- anxiety and arousal

- obsessions and compulsions

a.