15.1 Treatment: Getting Help to Those Who Need It

Estimates suggest that 46.4% of people in the United States suffer from a mental disorder at some point in their lifetimes (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005). The personal costs of these disorders involve anguish to the sufferers as well as interference in their ability to carry on the activities of daily life. Think about Christine from the example above. Her OCD was causing major problems in her life. She had to quit her job at the local coffee shop because she was no longer able to touch money or anything else that had been touched by other people without washing it first. Her relationship with her boyfriend was in trouble because he was growing tired of her constant reassurance-

The personal and social burdens associated with mental disorders are enormous, and there are financial costs too. Depression is the fourth leading cause of disability worldwide, and it is expected to rise to the second leading cause of disability by 2020 (Murray & Lopez, 1996a, 1996b). People with severe depression often are unable to make it into work due to their disorder, and even when they do make it into work, they often suffer from poor work performance. Recent estimates suggest that depression-

What are some of the personal, social, and financial costs of mental illness?

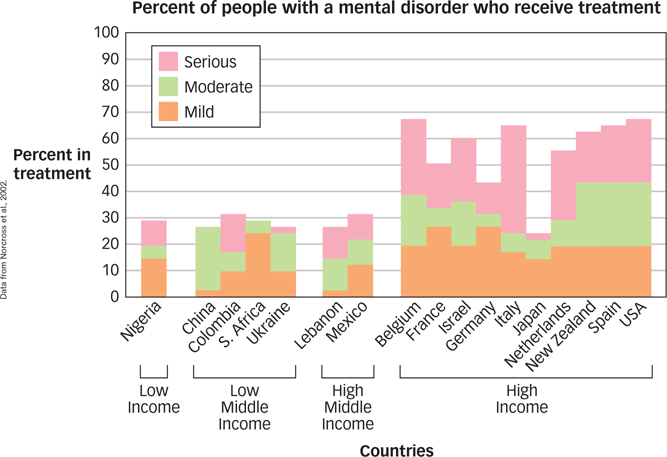

Unfortunately, only about 18% of people in the United States with a mental disorder in the past 12 months received treatment. Treatment rates are even lower elsewhere around the world, especially in low-

Why Many People Fail to Seek Treatment

A physical symptom such as a toothache would send most people to the dentist—

- People may not realize that they have a mental disorder that could be effectively treated. Approximately 45% of those with a mental disorder who do not seek treatment report that they did not do so because they didn’t think that they needed to be treated (Mojtabai et al., 2011). Although most people know what a toothache is and that it can be successfully treated, far fewer people know when they have a mental disorder and what treatments might be available.

- People’s attitudes may keep them from getting help. Individuals may believe that they should be able to handle things themselves. In fact, this is the primary reason that people with a mental disorder give for not seeking treatment (72.6%; Mojtabai et al., 2011). Other attitudinal barriers include perceived stigma from others (9.1%).

What are the obstacles to treatment for those with a mental illness?

- Structural barriers prevent people from physically getting to treatment. Like finding a good lawyer or plumber, finding the right psychologist can be difficult. This confusion is understandable given the plethora of different types of treatments available (see the Real World box, Types of Psychotherapists). Other structural barriers may include not being able to afford treatment (15.3% of nontreatment seekers), lack of clinician availability (12.8%), inconvenience of attending treatment (9.8%), and trouble finding transportation to the clinic (5.7%; Mojtabai et al., 2011).

479

The Real World: Types of Psychotherapists

Types of Psychotherapists

Therapists have widely varying backgrounds and training, and this affects the kinds of services they offer. There are several major “flavors.”

- Psychologist A psychologist who practices psychotherapy holds a doctorate with specialization in clinical psychology (a PhD or PsyD) and has extensive training in therapy, the assessment of psychological disorders, and research. The psychologist will sometimes have a specialty, such as working with adolescents or helping people overcome sleep disorders, and he or she will usually conduct therapy that involves talking. Psychologists must be licensed by the state.

- Psychiatrist A psychiatrist is a medical doctor who has completed a M.D. with specialized training in assessing and treating mental disorders. Psychiatrists can prescribe medications, and some also practice psychotherapy. General practice physicians can also prescribe medications for mental disorders, but they do not typically receive much training in the diagnosis or treatment of mental disorders, and they do not practice psychotherapy.

- Social worker Social workers have a master’s degree in social work and have training in working with people in dire life situations such as poverty, homelessness, or family conflict. Clinical or psychiatric social workers also receive training to help people in these situations who have mental disorders.

- Counselor In some states, a counselor must have a master’s degree and extensive training in therapy; other states require minimal training or relevant education. Counselors who work in schools usually have a master’s degree and specific training in counseling in educational settings.

Some people offer therapy under made-

People you know, such as your general practice physician, a school counselor, or a trusted friend or family member, might be able to recommend a good therapist. Or you can visit the American Psychological Association Web site for referrals to licensed mental health care providers.

Before you agree to see a therapist for treatment, you should ask questions to evaluate whether the therapist’s style or background is a good match for your problem:

- What type of therapy do you practice?

- What types of problems do you usually treat?

- Will our work involve “talking” therapy, medications, or both?

- How effective is this type of therapy for the type of problem I’m having?

- What are your fees for therapy, and will health insurance cover them?

Armed with the answers, you can make an informed decision about the type of service you need. The therapist’s personality is also critically important. You should seek out someone who is willing and open to answer questions, and who shows general respect and empathy for you. You’ll be entrusting the therapist with your mental health, and you should only enter into such a relationship when you and the therapist have good rapport.

480

Even when people seek and find help, they sometimes do not receive the most effective treatments, which further complicates things. For starters, most of the treatment of mental disorders is not provided by mental health specialists, but by general medical practitioners (Wang et al., 2007). And even when people make it to a mental health specialist, they do not always receive the most effective treatment possible. In fact, only a small percentage of those with a mental disorder (< 40%) receive what would be considered minimally adequate treatment. Clearly, before choosing or prescribing a therapy, we need to know what kinds of treatments are available and understand which treatments are best for particular disorders.

Approaches to Treatment

Treatments can be divided broadly into two kinds: (a) psychological treatment, in which people interact with a clinician in order to use the environment to change their brain and behavior; and (b) biological treatment, in which the brain is treated directly with drugs, surgery, or some other direct intervention. In some cases, both psychological and biological treatments are used. Christine’s OCD, for example, might be treated not only with ERP but also with medication that decreases her obsessive thoughts and compulsive urges. As we learn more about the biology and chemistry of the brain, approaches to mental health that begin with the brain are becoming increasingly widespread. As you’ll see later in the chapter, many effective treatments combine both psychological and biological interventions.

DATA VISUALIZATION

ADHD Diagnosis and Treatment www.macmillanhighered.com/

Culture & Community: Treatment of psychological disorders around the world

Treatment of psychological disorders around the world Barriers that keep people from receiving treatment for mental disorders exist all around the world. However, they are greater in some places than in others. One recent study examined what percentage of people with a mental disorder in 17 different countries around the world received treatment for their disorder in the past year (Wang et al., 2007). Several different findings are interesting to note. First, people with a severe mental disorder are much more likely to be treated. This makes sense. For instance, if your disorder is so severe that it prevents you from going to school or work, you will probably seek treatment, but if it doesn’t really interfere with your daily life you may not go for help. Second, people living in high-

481

SUMMARY QUIZ [15.1]

Question 15.1

| 1. | One of the most effective treatments for obsessive- |

- doing nothing because it will go away on its own.

- exposure and response prevention.

- bibliotherapy.

- Freudian psychoanalysis.

b.

Question 15.2

| 2. | Which of the following is NOT a reason why people fail to get treatment for mental illness? |

- People may not realize that their disorder needs to be treated.

- Levels of impairment for people with mental illness are not as high as those of people with chronic medical illnesses.

- There may be barriers to treatment, such as beliefs and circumstances that keep people from getting help.

- Even people who acknowledge they have a problem may not know where to look for services.

b.

Question 15.3

| 3. | Which of the following statements is true? |

- Mental illness is very rare, with only 1 person in 100 suffering from a psychological disorder.

- The majority of individuals with psychological disorders seek treatment.

- Women and men are equally likely to seek treatment for psychological disorders.

- Mental illness is often not taken as seriously as physical illness.

d.