Chapter 1 Introduction

1Psychology: Evolution of a Science

ii

1

Psychology’s Roots: The Path to a Science of Mind

Psychology’s Roots: The Path to a Science of Mind- THE REAL WORLD The Perils of Procrastination

- Psychology’s Ancestors: The Great Philosophers

- From the Brain to the Mind: The French Connection

- Structuralism: From Physiology to Psychology

- James and the Functional Approach

- THE REAL WORLD Improving Study Skills

The Development of Clinical Psychology

The Development of Clinical Psychology- The Path to Freud and Psychoanalytic Theory

- Influence of Psychoanalysis and the Humanistic Response

The Search for Objective Measurement: Behaviorism Takes Center Stage

The Search for Objective Measurement: Behaviorism Takes Center Stage- Watson and the Emergence of Behaviorism

- B. F. Skinner and the Development of Behaviorism

Return of the Mind: Psychology Expands

Return of the Mind: Psychology Expands- The Pioneers of Cognitive Psychology

- The Brain Meets the Mind: The Rise of Cognitive Neuroscience

- The Evolved Mind: The Emergence of Evolutionary Psychology

Beyond the Individual: Social and Cultural Perspectives

Beyond the Individual: Social and Cultural Perspectives- CULTURE & COMMUNITY Analytic and Holistic Styles in Western and Eastern Cultures

The Profession of Psychology: Past and Present

The Profession of Psychology: Past and Present- The Growing Role of Women and Minorities

- What Psychologists Do: Research Careers

- The Variety of Career Paths

- HOT SCIENCE Psychology as a Hub Science

A lot was happening in 1860. Abraham Lincoln had just been elected president of the United States, the Pony Express had just begun to deliver mail between Missouri and California, and a woman named Anne Kellogg had just given birth to a child who would one day grow up to invent the cornflake. But none of this mattered very much to William James (1842–

2

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. The mind refers to the private inner experience of perceptions, thoughts, memories, and feelings, an ever-

psychology

The scientific study of mind and behavior.

mind

The private inner experience of perceptions, thoughts, memories, and feelings.

behavior

Observable actions of human beings and nonhuman animals.

Question 1.1

1. Where does the mind come from?

For thousands of years, philosophers tried to understand how the objective, physical world of the body was related to the subjective, psychological world of the mind. Today, psychologists know that all of our subjective experiences arise from the electrical and chemical activities of our brains. As you will see throughout this book, some of the most exciting developments in psychological research focus on how our perceptions, thoughts, memories, and feelings are related to activity in the brain. Psychologists and neuroscientists are using new technologies to explore this relationship in ways that would have seemed like science fiction only 20 years ago.

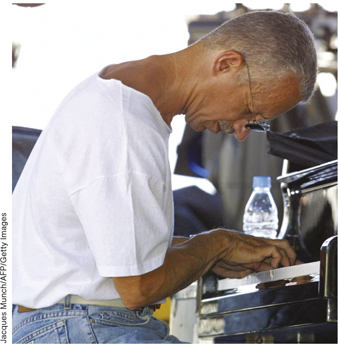

For example, the technique known as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) allows scientists to scan a brain to determine which parts are active when a person reads a word, sees a face, learns a new skill, or remembers a personal experience. In a recent study, the brains of both professional and novice pianists were scanned as they made complex finger movements, like those involved in piano playing. The results showed that professional pianists have less activity than novices in the parts of the brain that guide these finger movements (Krings et al., 2000). This finding suggests that extensive practice at the piano changes the brains of professional pianists and that the regions controlling finger movements operate more efficiently for them than they do for novices. You’ll learn more about how the brain learns in the Memory and Learning chapters, and you’ll see in the coming chapters how studies using fMRI and related techniques are beginning to transform many different areas of psychology.

Question 1.2

2. What is the mind for?

Human beings are animals, and like all animals, they must survive and reproduce. Minds help us accomplish those goals. For example, the ability to sense and perceive allows us to recognize our families, see predators before they see us, and avoid stumbling into oncoming traffic. Our linguistic abilities allow us to organize our thoughts and communicate them to others. Our ability to remember allows us to avoid solving the same problems every time we encounter them. Our capacity for emotion allows us to react quickly to events that have life or death significance. The list goes on, but the point is that each of these psychological processes serves a purpose or, as William James would have said, each “has a function.” That function becomes quite obvious the moment the process stops working. Consider, for example, the function of emotions.

Elliot was a middle-

Why was Elliot unable to make decisions after having brain surgery? After all, his intelligence was intact, and his ability to speak, think, and solve logical problems was every bit as sharp as ever. The problem, it turned out, was that Elliot was no longer able to experience emotions because the surgery to remove the tumor disrupted a part of Elliot’s brain tucked deep in the frontal lobes that plays a role in emotional experience (for further discussion of Elliot, see Chapter 9). For example, he didn’t experience anger when his boss gave him the pink slip, anxiety when he risked his life savings, or sorrow when his wives packed up and left. Most of us have wished from time to time that we could be as stoic and unflappable as that; after all, who needs anxiety, sorrow, and anger? The answer is that we all do.

3

Question 1.3

3. Why does the mind fail?

The mind is an amazing machine that can do many things quickly and well. We can guide a car through heavy traffic while talking to the person sitting next to us while keeping our eye out for the restaurant while listening to music. But like all machines that do many things at once, the mind occasionally makes mistakes. Consider these entries from the diaries of people who volunteered to keep track of all the mistakes they made in an ordinary day (Reason & Mycielska, 1982, pp. 70–

- I meant to get my car out, but as I passed the back porch on my way to the garage, I stopped to put on my boots and gardening jacket as if to work in the yard.

- I put some money into a machine to get a stamp. When the stamp appeared, I took it and said, “Thank you.”

- On leaving the room to go to the kitchen, I turned the light off, although several people were there.

These mistakes are familiar and amusing, but they are also potentially useful clues about the way the mind works. For example, the person who bought a stamp said, “Thank you,” but she did not say, “How do I find the subway?” The person said the wrong thing but did not say just any wrong thing: rather, the comment was simply wrong in that particular context (when buying stamps from a machine), but it would have been right in another (when buying stamps from a person). This tells us something quite interesting about the mind—