1.1 Psychology’s Roots: The Path to a Science of Mind

Psychology is a young science. William James once noted that “[t]he first lecture in psychology that I ever heard was the first I ever gave” (quoted in Perry, 1996, p. 228). Of course, that doesn’t mean no one had ever thought about human nature before psychology came along. For more than 2,000 years, philosophers have thought deeply and carefully about many of the issues with which modern psychology is concerned.

Psychology’s Ancestors: The Great Philosophers

What fundamental question has puzzled philosophers for millennia?

Plato (428 bce–347 bce) and Aristotle (384 bce–322 bce) were among the first philosophers to struggle with fundamental questions about how the mind works (Robinson, 1995). They and other Greek philosophers debated many of the questions that psychologists continue to debate today. For example, Plato was a strong proponent of nativism, the view that certain kinds of knowledge are innate or inborn. Aristotle, on the other hand, believed that the child’s mind was a “blank slate” on which only experience could write, and he was a strong proponent of what we now call philosophical empiricism, the view that all knowledge is acquired through experience. Interestingly, the debate between these two great thinkers is still alive today as modern psychologists work to understand the roles that “nature” and “nurture” play in determining our thoughts, feelings, and actions. The main difference is that whereas Plato and Aristotle were quite good at formulating positions, they couldn’t settle their debates because they had no objective means of testing those positions. As you will see in the Methods chapter, the ability to devise a theory and then test it is the cornerstone of the scientific approach that separates psychology and philosophy.

nativism

The philosophical view that certain kinds of knowledge are innate or inborn.

philosophical empiricism

The view that all knowledge is acquired through experience.

4

The Real World: The Perils of Procrastination

The Perils of Procrastination

William James understood that the human mind and human behavior are fascinating in part because they are not error free. Let’s consider a malfunction that can have significant consequences in your own life: procrastination.

At one time or another, most of us have avoided carrying out a task or we have put it off to a later time. The task may be unpleasant, difficult, or just less entertaining than other things we could be doing at the moment. For college students, procrastination can affect a range of academic activities, such as writing a term paper or preparing for a test.

Some procrastinators defend the practice by claiming that they tend to work best under pressure or by noting that as long as a task gets done, it doesn’t matter all that much if it is completed just before the deadline. Is there any merit to such claims, or are they just feeble excuses for counterproductive behavior?

A study of 60 undergraduate psychology college students provided some intriguing answers (Tice & Baumeister, 1997). At the beginning of the semester, the instructor announced a due date for the term paper and told students that if they could not meet the date, they would receive an extension to a later date. About a month later, students completed a scale that measures tendencies toward procrastination. At that same time and then again during the last week of class, students recorded health symptoms and levels of stress that they had experienced during the past week.

Students who scored high on the procrastination scale tended to turn in their papers late. One month into the semester, these procrastinators reported less stress and fewer symptoms of physical illness than did nonprocrastinators. But at the end of the semester, the procrastinators reported more stress and more health symptoms than did the nonprocrastinators, and the procrastinators also reported more visits to the health center. The procrastinators also received lower grades on their papers and on course exams. More recent studies have found that higher levels of procrastination are associated with poorer academic performance (Moon & Illingworth, 2005) and higher levels of psychological distress (Rice, Richardson, & Clark, 2012). Therefore, in addition to making use of the tips provided in the Real World box on improving study skills (p. 6), you would be wise to avoid procrastination in this course and others.

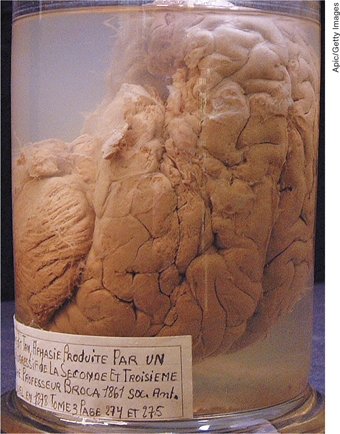

From the Brain to the Mind: The French Connection

We all know that the brain and the body are physical objects that we can see and touch; we also know that the subjective contents of our minds—

How did work involving patients with brain damage help demonstrate the relationship between mind and brain?

These kinds of questions proved to be difficult to answer, and the British philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588–

5

Structuralism: From Physiology to Psychology

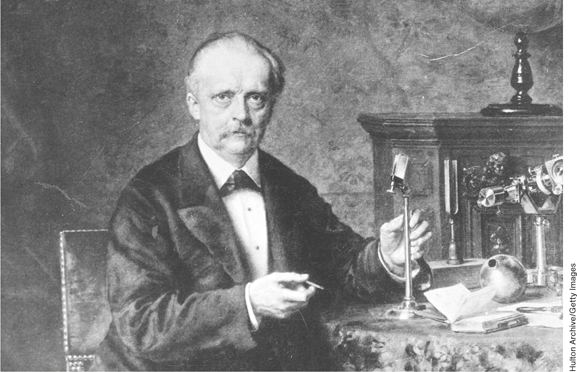

In an 1867 letter to a friend, William James wrote, “It seems to me that perhaps the time has come for psychology to begin to be a science. Helmholtz and a man called Wundt at Heidelberg are working at it.” So who were these guys?

Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–

reaction time

The amount of time taken to respond to a specific stimulus.

What was the useful application of Helmholtz’s results?

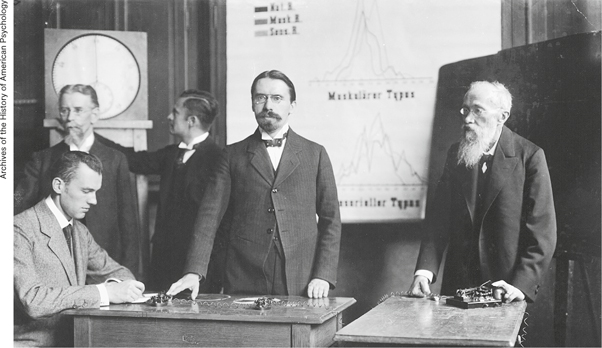

The other fellow whom William James admired was Wilhelm Wundt (1832-

How did the work of chemists influence early psychology?

consciousness

A person’s subjective experience of the world and the mind.

structuralism

The analysis of the basic elements that constitute the mind.

introspection

The subjective observation of one’s own experience.

6

James and the Functional Approach

William James agreed with Wundt on the importance of immediate experience and the usefulness of introspection as a technique (Bjork, 1983). But he disagreed with Wundt’s claim that consciousness could be broken down into separate elements. James believed that trying to isolate and analyze a particular moment of consciousness was absurd because consciousness was like a flowing stream that could only be understood in its entirety. Furthermore, he felt that Wundt was asking the wrong question: He was asking what consciousness was made of rather than what consciousness was for. So James developed an approach now known as functionalism, which is the study of the purpose that mental processes serve. (See the Real World box for some strategies to enhance one of the functions of mental processes—

functionalism

The study of the purpose mental processes serve in enabling people to adapt to their environment.

The Real World: Improving Study Skills

Improving Study Skills

Our minds don’t work like video cameras, recording everything that happens and then faithfully storing the information. In order to retain new information, you need to take an active role in learning by doing such things as rehearsing, interpreting, and testing yourself. These activities initially might seem difficult, but in fact they are what psychologists call desirable difficulties (Bjork & Bjork, 2011): Making an activity more difficult by actively engaging during learning will increase your retention and ultimately result in improved performance. Here are four specific suggestions:

- Rehearse. One useful type of active manipulation is rehearsal: repeating to-

be- learned information to yourself. For example, suppose you want to learn the name of a person you’ve just met. Repeat the name to yourself right away; wait a few seconds and think of it again; wait a bit longer (maybe 30 seconds), and bring the name to mind once more; then rehearse the name again after a minute and once more after 2 or 3 minutes. This type of spaced rehearsal improves long- term learning more than rehearsing the name without any spacing between rehearsals (Landauer & Bjork, 1978). You can apply this technique to names, dates, definitions, and many other kinds of information, including concepts presented in this textbook. - Interpret. If we think deeply enough about what we want to remember, the act of reflection itself will virtually guarantee good memory. The Changing Minds scenarios at the end of each chapter require you to review what you’ve learned in the chapter and to relate it to other things you already know about, which in turn will make you more likely to remember the information.

- Test. Don’t just look at your class notes or this textbook; test yourself on the material as often as you can. Actively testing yourself helps you to later remember that information more than just looking at it again. The Cue Questions that you will encounter throughout the text (highlighted by green question marks) are designed to test you and thereby increase learning and retention. Be sure to use them.

- Hit the main points. Take some of the load off your memory by developing effective note-

taking and outlining skills. Realize that you can’t write down everything an instructor says, so try to focus on making detailed notes about the main ideas, facts, and people mentioned in the lecture. Later, organize your notes into an outline that clearly highlights the major concepts. This will force you to reflect on the information in a way that promotes retention and will also provide you with a helpful study guide to promote self- testing and review.

These four activities may seem difficult or demanding at first, but they will result in improved retention and ultimately will make learning easier for you.

7

How does functionalism relate to Darwin’s theory of natural selection?

James was inspired not only by Helmholtz and Wundt, but also by the naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–

natural selection

Charles Darwin’s theory that the features of an organism that help it survive and reproduce are more likely than other features to be passed on to subsequent generations.

SUMMARY QUIZ [1.1]

Question 1.4

| 1. | In the 1800s, Paul Broca conducted research that demonstrated a connection between |

- animals and humans.

- the mind and the brain.

- brain size and mental ability.

- skull indentations and psychological attributes.

b.

Question 1.5

| 2. | What was the subject of the famous experiment conducted by Hermann von Helmholtz? |

- reaction time

- childhood learning

- structuralism

- functions of specific brain areas

a.

Question 1.6

| 3. | Wundt and his students sought to analyze the basic elements that constitute the mind, an approach called |

- consciousness.

- introspection.

- structuralism.

- objectivity.

c.

Question 1.7

| 4. | William James developed _______, the study of the purpose mental processes serve in enabling people to adapt to their environments. |

- empiricism

- nativism

- structuralism

- functionalism

d.

8