1.6 The Profession of Psychology: Past and Present

In 1892, William James and six other psychologists came together for a meeting at Clark University. Although there were too few of them to make up a jury or even a respectable hockey team, these seven men decided that it was time to form an organization that represented psychology as a profession, and on that day, the American Psychological Association (APA) was born. The seven psychologists could scarcely have imagined that today their little club would have more than 150,000 members from all over the world. Although all of the original members were professors, 70% of the current members work in clinical and health-

The Growing Role of Women and Minorities

How has the face of psychology changed as the field has evolved?

In 1892, the APA had 31 members, all of whom were White men. Today, about half of all APA members are women, and the percentage of non-

The current involvement of women and minorities in the APA and in psychology more generally can be traced to early pioneers who blazed a trail that others followed. In 1905, Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–

Just as there were no women at the first meeting of the APA, there weren’t any non-

21

What Psychologists Do: Research Careers

Before describing what psychologists do, it should be noted that most people who major in psychology do not go on to become psychologists. Psychology has become a major academic, scientific, and professional discipline with links to many other disciplines and career paths (see the Hot Science box). That being said, what should you do if you do want to become a psychologist, and what should you fail to do if you desperately want to avoid it? You can become “a psychologist” by a variety of routes, and the people who call themselves psychologists may hold a variety of different degrees. Students intending to pursue careers in psychology typically finish college and enter graduate school in order to obtain a PhD (or doctor of philosophy) degree in some particular area of psychology (e.g., social, cognitive, developmental). During graduate school, students generally gain exposure to the field by taking classes and learn to conduct research by collaborating with their professors. Although William James was able to master every area of psychology because the areas were so small during his lifetime, today a student can spend the better part of a decade mastering just one.

After receiving a PhD, students often go on for more specialized research training by pursuing a postdoctoral fellowship under the supervision of an established researcher in his or her area, or they apply for a faculty position at a college or university or a research position in government or industry. Academic careers usually involve a combination of teaching and research, whereas careers in government or industry are typically dedicated to research alone.

The Variety of Career Paths

But research is not the only career option for a psychologist. Most people who call themselves psychologists neither teach nor do research, but rather, they assess or treat people with psychological problems. Most of these clinical psychologists work in private practice, often in partnerships with other psychologists or with psychiatrists (who have earned an MD, or medical degree, and are allowed to prescribe medication). Other clinical psychologists work in hospitals or medical schools, some have faculty positions at universities or colleges, and some combine private practice with an academic job. Many clinical psychologists focus on specific problems or disorders, such as depression or anxiety, whereas others focus on specific populations, such as children, ethnic minority groups, or older adults (see FIGURE 1.2). Just over 10% of APA members are counseling psychologists, who assist people in dealing with work or career issues and changes or help people deal with common crises such as divorce, the loss of a job, or the death of a loved one.

Courtesy Dipti Kapania

Courtesy Constance Stevens

22

Hot Science: Psychology as a Hub Science

Psychology as a Hub Science

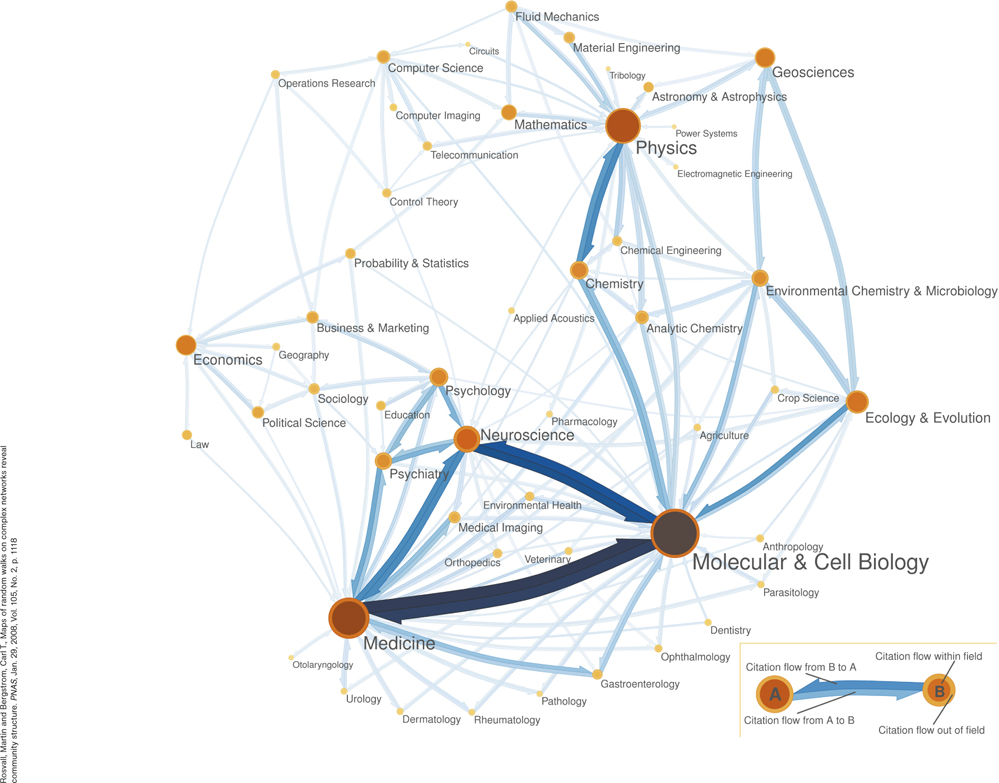

This chapter describes how psychology emerged as a field of study and illustrates some of the ways in which psychology is indeed a scientific field of study. But where does psychology stand in relation to other areas of science? With recent advances in computing and electronic record keeping, researchers are now able to literally create maps of science. Information about scientific articles, about the journals in which they are published, and about the frequency and patterns with which articles in one field are cited by articles in another field is now fully electronic and available online (in the Science Citation and Social Science Citation Indexes).

As an example, in an article called “Mapping the Backbone of Science,” Kevin Boyack and his colleagues (2005) used data from more than 1 million articles, with more than 23 million references, published in more than 7,000 journals, to create a map showing the similarities and interconnectedness of different areas of science based on how frequently journal articles from different disciplines cite each other. The results are fascinating. As shown in the figure, seven major fields, or “hub sciences,” emerged in the data: math, physics, chemistry, earth sciences, medicine, psychology, and social science. There were also smaller subfields that fell between the hub sciences: public health and neurology fall between psychology and medicine, statistics between psychology and math, and economics between social science and math.

Another study, which used data from more than 6 million citations found in more than 6,000 journals, led to the creation of a map of citation patterns focusing only on citations to articles published in a recent five-

Studies like these are useful to university administrators, funding agencies, and also to students to help them understand the relationships between different academic departments and how the scientific work of one field relates to the scientific field more broadly. They also show the reach of psychology to other disciplines and support the idea that knowledge about psychology has relevance for many r elated disciplines and career paths. Good thing you are taking this class!

In what ways does psychology contribute to society?

Psychologists are also quite active in educational settings. About 5% of APA members are school psychologists, who offer guidance to students, parents, and teachers. A similar proportion of APA members, known as industrial/organizational psychologists, focus on issues in the workplace. These psychologists typically work in business or industry and may be involved in assessing potential employees, finding ways to improve productivity, or in helping staff and management to develop effective planning strategies for coping with change or anticipated future developments. Of course, this brief list doesn’t begin to cover all the different career paths that someone with training in psychology might take. For instance, sports psychologists help athletes improve their performances, forensic psychologists assist attorneys and courts, and consumer psychologists help companies develop and advertise new products. Indeed, we can’t think of any major enterprise that doesn’t employ psychologists.

23

DATA VISUALIZATION

Understanding How to Read and Use

(or misuse!) Data

www.macmillanhighered.com/

launchpad/

Even this brief and incomplete survey of the APA membership provides a sense of the wide variety of contexts in which psychologists operate. You can think of psychology as an international community of professionals devoted to advancing scientific knowledge; assisting people with psychological problems and disorders; and trying to enhance the quality of life in work, school, and other everyday settings.

24

SUMMARY QUIZ [1.6]

Question 1.20

| 1. | Mary Whiton Calkins |

- studied with Wilhelm Wundt in the first psychology laboratory.

- did research on the self-

image of African American children. - was present at the first meeting of the APA.

- became the first woman president of the APA.

d.

Question 1.21

| 2. | Kenneth Clark |

- did research that influenced the Supreme Court decision to ban segregation in public schools.

- was one of the founders of the APA.

- was a student of William James.

- did research that focused on the education of African American youth.

a.