6.4 Multiple Forms of Memory: How the Past Returns

In 1977, neurologist Oliver Sacks interviewed a young man named Greg who had a tumor in his brain that wiped out his ability to remember day-

Although Greg was unable to make new memories, some of the new things that happened to him seemed to leave a mark. For example, Greg did not recall learning that his father had died, but he did seem sad and withdrawn for years after hearing the news. Similarly, HM could not make new memories after his surgery, but if he played a game in which he had to track a moving target, his performance gradually improved with each round (Milner, 1962). Greg could not consciously remember hearing about his father’s death, and HM could not consciously remember playing the tracking game, but both men showed clear signs of having been permanently changed by experiences that they so rapidly forgot. In other words, they behaved as though they were remembering things while claiming to remember nothing at all. This suggests that there must be several kinds of memory, some that are accessible to conscious recall, and some that we cannot consciously access (Eichenbaum & Cohen, 2001; Schacter & Tulving, 1994; Schacter, Wagner, & Buckner, 2000; Squire & Kandel, 1999).

187

Explicit and Implicit Memory

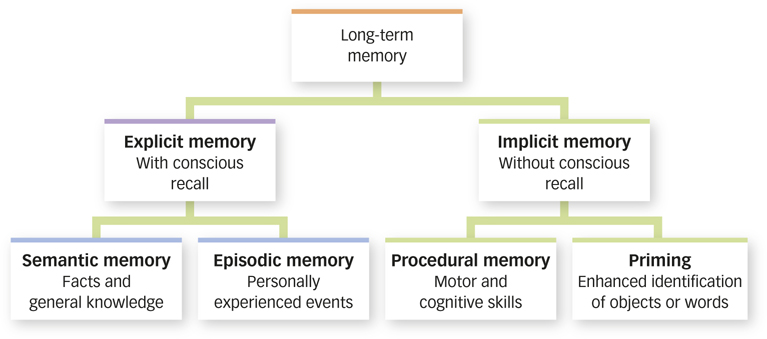

The fact that people can be changed by past experiences without having any awareness of those experiences suggests that there must be at least two different classes of memory (FIGURE 6.11). Explicit memory occurs when people consciously or intentionally retrieve past experiences. Recalling last summer’s vacation, incidents from a novel you just read, or facts you studied for a test all involve explicit memory. Indeed, anytime you start a sentence with “I remember …,” you are talking about an explicit memory. Implicit memory occurs when past experiences influence later behavior and performance, even without an effort to remember those experiences or an awareness of the recollection (Graf & Schacter, 1985; Schacter, 1987). Implicit memories are not consciously recalled, but their presence is “implied” by our actions. Greg’s persistent sadness after his father’s death, even though he had no conscious knowledge of the event, is an example of implicit memory. So is HM’s improved performance on a tracking task that he didn’t consciously remember doing. So is the ability to ride a bike or tie your shoelaces or play guitar: You may know how to do these things, but you probably can’t describe how to do them. Such knowledge reflects a particular kind of implicit memory called procedural memory, which refers to the gradual acquisition of skills as a result of practice, or “knowing how” to do things. The fact that people who have amnesia can acquire new procedural memories suggests that the hippocampal structures that are usually damaged in these individuals may be necessary for explicit memory, but they aren’t needed for implicit procedural memory. In fact, it appears that brain regions outside the hippocampal area (including areas in the motor cortex) are involved in procedural memory. The Learning chapter discusses this evidence further, where you will also see that procedural memory is crucial for learning various kinds of motor, perceptual, and cognitive skills.

explicit memory

The act of consciously or intentionally retrieving past experiences.

implicit memory

The influence of past experiences on later behavior and performance, even without an effort to remember them or an awareness of the recollection.

procedural memory

The gradual acquisition of skills as a result of practice, or “knowing how” to do things.

What type of memory is it when you just “know how” to do something?

188

Not all implicit memories are procedural or “how to” memories. For example, priming refers to an enhanced ability to think of a stimulus, such as a word or object, as a result of a recent exposure to the stimulus (Tulving & Schacter, 1990). In one experiment, college students were asked to study a long list of words, including items such as avocado, mystery, climate, octopus, and assassin (Tulving, Schacter, & Stark, 1982). Later, explicit memory was tested first by showing participants some of these words along with new ones they hadn’t seen and then by asking them which words were on the list. To test implicit memory, participants received word fragments and were asked to come up with a word that fit the fragment. Try the test yourself:

priming

An enhanced ability to think of a stimulus, such as a word or object, as a result of a recent exposure to the stimulus.

You probably had difficulty coming up with the answers for the first and third fragments (chipmunk, bogeyman) but had little problem coming up with answers for the second and fourth (octopus, climate). Seeing octopus and climate on the original list made those words more accessible later during the fill-

How does priming make memory more efficient?

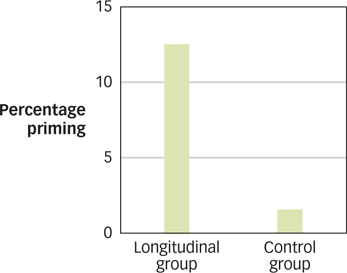

A truly stunning example of this point comes from a study by Mitchell (2006), in which participants first studied black-

As such, you’d expect amnesic individuals such as HM and Greg to show priming. In fact, many experiments have shown that amnesic individuals can show substantial priming effects—

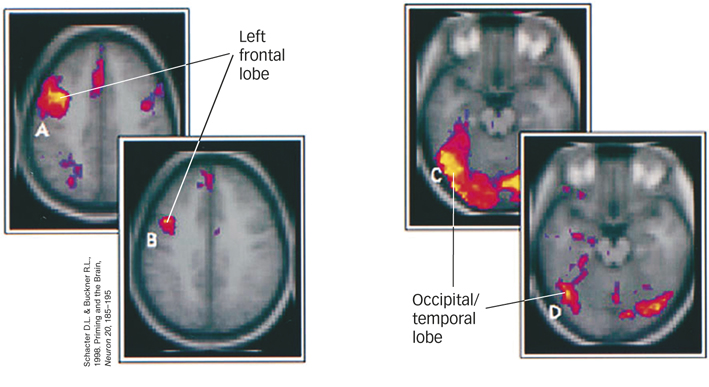

If the hippocampal region isn’t required for priming, what parts of the brain are involved? When research participants are shown the word stem mot___ or tab___ and are asked to provide the first word that comes to mind, parts of the occipital lobe involved in visual processing and parts of the frontal lobe involved in word retrieval become active. But if people perform the same task after being primed by seeing motel and table, there’s less activity in these same regions (Buckner et al., 1995; Schott et al., 2005). Priming seems to make it easier for parts of the cortex that are involved in perceiving a word or object to identify the item after a recent exposure to it (Schacter, Dobbins, & Schnyer, 2004; Wiggs & Martin, 1998). This suggests that the brain saves a bit of processing time after priming (see FIGURE 6.13).

189

Semantic and Episodic Memory

Consider these two questions: (1) Why do Americans celebrate on July 4th? and (2) What is the most spectacular Fourth of July celebration you’ve ever seen? Every American knows the answer to the first question (we celebrate the signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776), but we all have our own answers to the second. Although both of these questions require you to search your long-

semantic memory

A network of associated facts and concepts that make up our general knowledge of the world.

episodic memory

The collection of past personal experiences that occurred at a particular time and place.

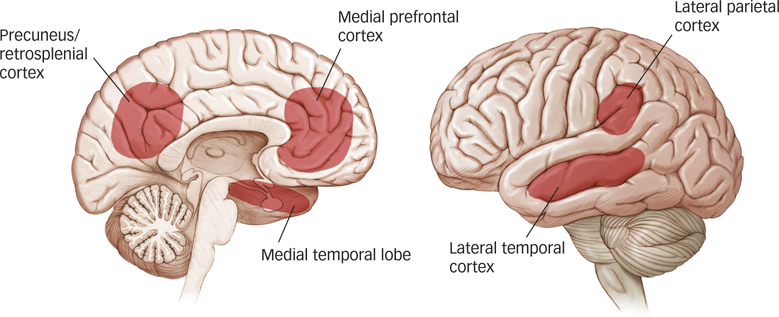

Episodic memory is special because it is the only form of memory that allows us to engage in mental time travel, projecting ourselves into the past and revisiting events that have happened to us. This ability allows us to connect our pasts and our presents and construct a cohesive story of our lives. People who have amnesia can usually travel back in time and revisit episodes that occurred before they became amnesic, but they are unable to revisit episodes that happened later. For example, Greg couldn’t travel back to any time after 1969 because that’s when he stopped being able to create new episodic memories. But can people with amnesia create new semantic memories?

What form of memory uses mental time travel?

Researchers have studied three young adults who suffered damage to the hippocampus during birth as a result of difficult deliveries that interrupted oxygen supply to the brain (Brandt et al., 2009; Vargha-

190

Episodic Memory and Imagining the Future

We’ve already seen that episodic memory allows us to travel backward in time, but it turns out that episodic memory also plays a role in allowing us to travel forward in time. An amnesic man known by the initials K.C. provided an early clue to this insight about traveling forward in time. K.C. could not recollect any specific episodes from his past, and when asked to imagine a future episode—

How does episodic memory help us imagine our futures?

Taken together, these observations strongly suggest that we rely heavily on episodic memory to envision our personal futures (Schacter, Addis, & Buckner, 2008; Szpunar, 2010). Episodic memory is well-

191

Social Influences on Remembering: Collaborative Memory

So far, we’ve focused mainly on memory in individuals functioning on their own. But remembering also serves important social functions, which is why we get together with family to talk about old times or share our memories with friends by posting our vacation photos on Facebook. Sharing memories with others can strengthen those memories (Hirst & Echterhoff, 2012), but we’ve already seen that talking about some aspects of a memory but omitting other related events can also produce retrieval-

Why does a collaborative group typically recall fewer items than individuals recalling items on their own?

In a typical collaborative memory experiment, participants first encode a set of target materials, such as a list of words, on their own (just like in the traditional memory experiments that we’ve already considered). Things start to get interesting at the time of retrieval when participants work together in small groups (usually two or three participants) to try to remember the target items. The number of items recalled by this group can then be compared with the number of items recalled by individuals who are trying to recall items on their own without any help from others. The collaborative group typically recalls more target items than any individual (Hirst & Echterhoff, 2012; Weldon, 2001), suggesting that collaboration benefits memory. For example, Tim might recall an item that Emily forgot, and Eric might remember items that neither Tim nor Emily recalled, so the sum total of the group will exceed what any one person can recall.

But things get really interesting when we compare the performance of the collaborative group to the performance of several individuals recalling target items on their own. For example, let’s assume that after studying a list of eight words, and recalling the items on their own, Tim recalls items 1, 2, and 8; Emily recalls items 1, 4, and 7; and Eric recalls items 1, 5, 6, and 8. Adding them all together, Tim, Emily, and Eric recalled in combination seven of the eight items that were presented (nobody recalled item 3). The surprising finding is that when they remember together as a group, Tim, Emily, and Eric will typically come up with fewer total items than when they remember on their own (Basden et al., 1997; Hirst & Echterhoff, 2012; Rajaram, 2011; Rajaram & Pereira-

192

What’s going on here? One possibility is that the retrieval strategies used by some members of the group disrupt those used by others whenever the group members are recalling items together (Basden et al., 1997; Hirst & Echterhoff, 2012; Rajaram, 2011). For example, suppose that Tim goes first and recalls items in the order that they were presented. This retrieval strategy may be disruptive to Emily, who prefers to recall the last item first and then work backward through the list. So, next time you are sharing memories of a past activity with friends, you will be shaping your memories for both better and worse. (Can you rely on your computer for collaborative remembering? See The Real World: Is Google Hurting Our Memories?)

The Real World: Is Google Hurting our Memories?

Is Google Hurting our Memories?

Take some time to try to answer a simple question before returning to reading this box: What country has a national flag that is not rectangular? Now let’s discuss what went through your mind as you searched for an answer (the correct one is Nepal). There was probably a time not too long ago when most people would have tried to conjure up images of national flags or take a mental world tour to try to answer this question, but recent research conducted in the lab of one of your textbook authors indicates that nowadays, most of us think about computers and Google searches when confronted with questions of this kind (Sparrow, Liu, & Wegner, 2011).

Sparrow et al. found that after being given difficult general knowledge questions (like the one about nonrectangular flags), people were slower to name the color in which a computer word (e.g., Google, internet, Yahoo) was printed than the color in which a noncomputer word was printed (e.g., Nike, table, Yoplait). The slow-

In follow-

193

SUMMARY QUIZ [6.4]

Question 6.10

| 1. | The act of consciously or intentionally retrieving past experiences is |

- priming.

- procedural memory.

- implicit memory.

- explicit memory.

d.

Question 6.11

| 2. | People who have amnesia are able to retain all of the following except |

- explicit memory.

- implicit memory.

- procedural memory.

- priming.

a.

Question 6.12

| 3. | Remembering a family reunion that you attended as a child illustrates |

- semantic memory.

- procedural memory.

- episodic memory.

- perceptual priming.

c.