7.1 Classical Conditioning: One Thing Leads to Another

American psychologist John B. Watson kick-

Pavlov studied the digestive processes of laboratory animals by surgically implanting test tubes into the cheeks of dogs to measure their salivary responses to different foods. Serendipitously, his explorations into spit and drool revealed a form of learning, which came to be called classical conditioning. Classical conditioning occurs when a neutral stimulus produces a response after being paired with a stimulus that naturally produces a response. Pavlov showed that dogs learned to salivate to a neutral stimulus, such as a bell or a tone, after that stimulus had been associated with another stimulus that naturally evokes salivation, such as food.

classical conditioning

A type of learning that occurs when a neutral stimulus produces a response after being paired with a stimulus that naturally produces a response.

The Development of Classical Conditioning: Pavlov’s Experiments

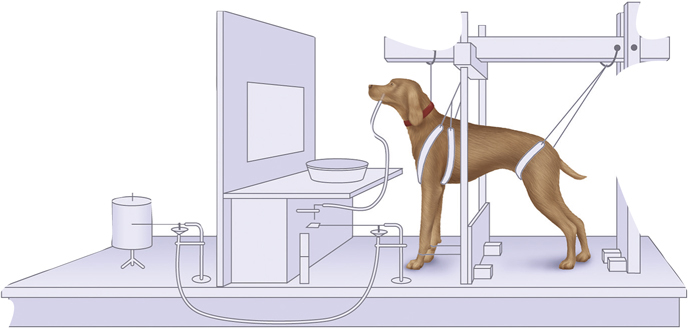

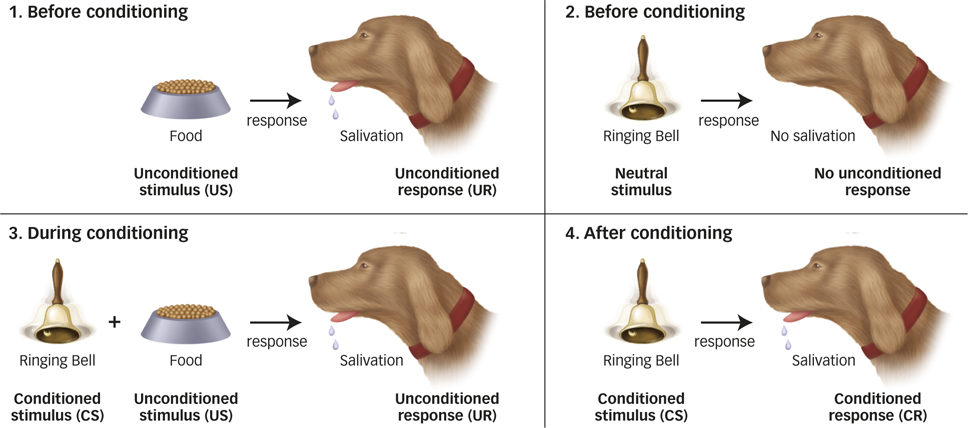

Pavlov’s basic experimental setup involved cradling dogs in a harness to administer the foods and to measure the salivary response, as shown in FIGURE 7.1. He noticed that dogs that had previously been in the experiment began to produce a kind of “anticipatory” salivary response as soon as they were put in the harness, before any food was presented. Pavlov and his colleagues regarded these responses as annoyances at first because they interfered with collecting naturally occurring salivary secretions. In reality, the dogs were exhibiting classical conditioning. When the dogs were initially presented with a plate of food, they began to salivate. No surprise here. Pavlov called the presentation of food an unconditioned stimulus (US), something that reliably produces a naturally occurring reaction in an organism. He called the dogs’ salivation an unconditioned response (UR), a reflexive reaction that is reliably produced by an unconditioned stimulus.

unconditioned stimulus (US)

Something that reliably produces a naturally occurring reaction in an organism.

unconditioned response (UR)

A reflexive reaction that is reliably produced by an unconditioned stimulus.

Pavlov soon discovered that he could make the dogs salivate to other stimuli, such as the ringing of a bell or the flash of a light (Pavlov, 1927). Each of these stimuli was a conditioned stimulus (CS), a previously neutral stimulus that produces a reliable response in an organism after being paired with a US (see FIGURE 7.2). When the conditioned stimulus, such as the sound of a bell, is paired over time with the US (food), the animal will learn to associate food with the sound, and eventually, the CS is sufficient to produce a response (in this case, salivation). Pavlov called this response the conditioned response (CR), a reaction that resembles an unconditioned response but is produced by a conditioned stimulus. In this example, the dogs’ salivation (CR) was prompted by the sound of the bell (CS) because the bell and the food (US) had been associated so often in the past.

conditioned stimulus (CS)

A previously neutral stimulus that produces a reliable response in an organism after being paired with a US.

conditioned response (CR)

A reaction that resembles an unconditioned response but is produced by a conditioned stimulus.

210

Why do some dogs seem to know when it’s dinnertime?

Consider your own dog (or cat). Does your dog always know when dinner’s coming, as though she has one eye on the clock every day, waiting for the dinner hour? Alas, your dog is no clock-

The Basic Principles of Classical Conditioning

When Pavlov’s findings first appeared (Pavlov, 1923a, 1923b), they produced a flurry of excitement. Classical conditioning was the kind of behaviorist psychology Watson was proposing: An organism experiences stimuli that are observable and measurable, and changes in that organism can be directly observed and measured. Dogs learned to salivate to the sound of a buzzer, and there was no need to resort to explanations about why it had happened, what the dog wanted, or how the animal thought about the situation. Pavlov also appreciated the significance of his discovery and embarked on a systematic investigation of the mechanisms of classical conditioning. Let’s take a closer look at some of these principles. (As the Real World box shows, these principles help explain how drug overdoses occur.)

Acquisition

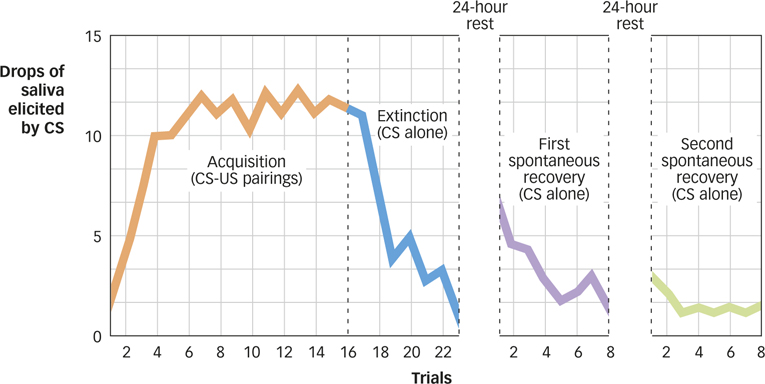

Remember when you first got your dog? Chances are she didn’t seem too smart, especially the way she stared at you vacantly as you went into the kitchen, not anticipating that food was on the way. That’s because learning through classical conditioning requires some period of association between the CS and US. This period is called acquisition, the phase of classical conditioning when the CS and the US are presented together. Typically, learning starts low, rises rapidly, and then slowly tapers off, as shown on the left side of FIGURE 7.3. Pavlov’s dogs gradually increased their amount of salivation over several trials of pairing a tone with the presentation of food, and similarly, your dog eventually learned to associate your kitchen preparations with the subsequent appearance of food. After learning has been established, the CS by itself will reliably elicit the CR.

acquisition

The phase of classical conditioning when the CS and the US are presented together.

211

Second-Order Conditioning

After conditioning has been established, second-order conditioning can be demonstrated: conditioning in which a CS is paired with a stimulus that became associated with the US in an earlier procedure. For example, in an early study, Pavlov repeatedly paired a new CS, a black square, with the now reliable tone. After a number of training trials, his dogs produced a salivary response to the black square even though the square itself had never been directly associated with the food. Second-

second-order conditioning

Conditioning in which a CS is paired with a stimulus that became associated with the US in an earlier procedure.

Extinction and Spontaneous Recovery

After Pavlov and his colleagues had explored the process of acquisition, they wondered what would happen if they continued to present the CS (tone) but stopped presenting the US (food). As shown on the right side of the first panel in FIGURE 7.3, behavior declines abruptly and continues to drop until eventually, the dog ceases to salivate at the sound of the tone. This process is called extinction, the gradual elimination of a learned response that occurs when the CS is repeatedly presented without the US. The term was introduced because the conditioned response is “extinguished” and no longer observed.

extinction

The gradual elimination of a learned response that occurs when the CS is repeatedly presented without the US.

How does conditioned behavior change when the unconditioned stimulus is removed?

Pavlov next wondered if this elimination of conditioned behavior was permanent. When the dogs were brought back to the lab and presented with the CS again, they displayed spontaneous recovery, the tendency of a learned behavior to recover from extinction after a rest period. This phenomenon is shown in the middle panel in FIGURE 7.3. Notice that this recovery takes place even though there have not been any additional associations between the CS and US. Some spontaneous recovery of the conditioned response even takes place after a period of rest (see the right-

spontaneous recovery

The tendency of a learned behavior to recover from extinction after a rest period.

Generalization and Discrimination

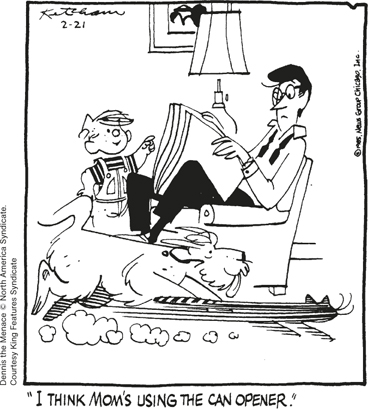

How can a change in the can opener affect a conditioned dog’s response?

Do you think your dog will be stumped, unable to anticipate the presentation of her food, if you get a new can opener? Will a whole new round of conditioning need to be established with this modified CS?

212

Probably not. It wouldn’t be very adaptive for an organism if each little change in the CS-

generalization

The CR is observed even though the CS is slightly different from the CS used during acquisition.

discrimination

The capacity to distinguish between similar but distinct stimuli.

Conditioned Emotional Responses: The Case of Little Albert

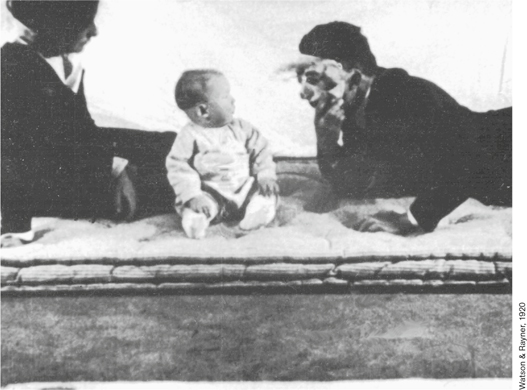

Watson and his followers thought that it was possible to develop general explanations of pretty much any behavior of any organism based on classical conditioning principles. As a step in that direction, Watson embarked on a controversial study with his research assistant Rosalie Rayner (Watson & Rayner, 1920) to see if a healthy, well-

The Real World: Understanding Drug Overdoses

Understanding Drug Overdoses

All too often, police are confronted with a perplexing problem: the sudden death of heroin addicts from a drug overdose. The victims are often experienced drug users; the dose taken is usually not larger than what they usually take; and the deaths tend to occur in unusual settings.

Classical conditioning provides some insight into how these deaths occur. First, when classical conditioning takes place, the CS is more than a simple bell or tone: It also includes the overall context within which the conditioning takes place. In the case of heroin, when the drug is injected, the entire setting (the drug paraphernalia, the room, the lighting, the addict’s usual companions) functions as the CS. Second, many CRs are compensatory in nature, counteracting the anticipated effects of the US. Heroin, for example, causes many changes in the body, such as slower breathing, so the body responds by speeding up breathing in order to maintain a state of balance. Over time, this protective physiological response becomes part of the CR, and like all CRs, it occurs in the presence of the CS but prior to the actual administration of the US (in this case, the heroin). These compensatory physiological reactions are also what make drug abusers take increasingly larger doses to achieve the same effect. Ultimately, these reactions produce drug tolerance, discussed in the Consciousness chapter.

Based on these principles of classical conditioning, taking drugs in a new environment can be fatal for a longtime drug user. If an addict injects the usual dose in a setting that is sufficiently novel or where heroin has never been taken before, the CS is now altered, so that the physiological compensatory CR that usually serves a protective function may not occur (Siegel et al., 2000). As a result, the addict’s usual dose becomes an overdose, and death often results. Understanding these principles has led to treatments for drug addicts. For example, the brain’s compensatory response to a drug, when elicited by the familiar contextual cues ordinarily associated with drug taking that constitute the CS, can be experienced by the addict as withdrawal symptoms. In cue exposure therapies, an addict is exposed to drug-

213

Watson presented Little Albert with a variety of stimuli: a white rat, a dog, a rabbit, various masks, and a burning newspaper. Albert’s reactions in most cases were curiosity or indifference, and he showed no fear of any of the items. Watson also established that something could make Albert afraid. While Albert was watching Rayner, Watson unexpectedly struck a large steel bar with a hammer, producing a loud noise. Predictably, this caused Albert to cry, tremble, and be generally displeased.

Watson and Rayner then led Little Albert through the acquisition phase of classical conditioning. Albert was presented with a white rat. As soon as he reached out to touch it, the steel bar was struck. This pairing occurred again and again over several trials. Eventually, the sight of the rat alone caused Albert to recoil in terror. In this situation, a US (the loud sound) was paired with a CS (the presence of the rat) such that the CS all by itself was sufficient to produce the CR (a fearful reaction). Little Albert also showed stimulus generalization. The sight of a white rabbit, a seal-

Why did Albert fear the rat?

This study was controversial in its cavalier treatment of a young child. Modern ethical guidelines that govern the treatment of research participants make sure that this kind of study could not be conducted today. So, what was Watson’s goal in all this? First, he wanted to show that a relatively complex reaction could be conditioned using Pavlovian techniques. Second, he wanted to show that emotional responses such as fear and anxiety could be produced by classical conditioning and therefore need not be the product of deeper unconscious processes. Instead, Watson proposed that fears could be learned, just like any other behavior.

The kind of conditioned fear responses that were at work in Little Albert’s case were also important in the chapter-

A Deeper Understanding of Classical Conditioning

As a form of learning, classical conditioning has a simple set of principles and applications to real-

214

The Cognitive Elements of Classical Conditioning

Pavlov’s work was a behaviorist’s dream come true. In this view, conditioning is something that happens to a dog, a rat, or a person, apart from what the organism thinks about the conditioning situation. However, although the dogs salivated when their feeders approached (see the Psychology: Evolution of a Science chapter), they did not salivate when Pavlov did. Eventually, someone was bound to ask an important question: Why not? After all, Pavlov also delivered the food to the dogs, so why didn’t he become a CS? Indeed, if Watson was present whenever the unpleasant US was sounded, why didn’t Little Albert come to fear him?

Somehow, Pavlov’s dogs were sensitive to the fact that Pavlov was not a reliable indicator of the arrival of food. Pavlov was linked with the arrival of food, but he was also linked with other activities that had nothing to do with food, including checking on the apparatus, bringing the dog from the kennel to the laboratory, and standing around and talking with his assistants.

Robert Rescorla and Allan Wagner (1972) were the first to theorize that classical conditioning occurs when an animal has an expectation. The bell, because of its systematic pairing with food, served to set up this cognitive state for the laboratory dogs; Pavlov, because of the lack of any reliable link with food, did not. The Rescorla–

How does the role of expectation in conditioning challenge behaviorist ideas?

The Neural Elements of Classical Conditioning

Pavlov saw his research as providing insights into how the brain works. Recent research has clarified some of what Pavlov hoped to understand about conditioning and the brain.

Richard Thompson and his colleagues focused on classical conditioning of eyeblink responses in the rabbit, in which the CS (a tone) is immediately followed by the US (a puff of air), which elicits a reflexive eyeblink response. After many CS–

What is the role of the amygdala in fear conditioning?

Also in the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter, you saw that the amygdala plays an important role in the experience of emotion, including fear and anxiety. So, it should come as no surprise that the amygdala is also critical for emotional conditioning. Normal rats, trained so that a tone (CS) predicts a mild electric shock (US), show a defensive reaction (CR), known as freezing, where they crouch down and sit motionless. If connections linking the amygdala to the midbrain are disrupted, the rat does not exhibit the behavioral freezing response. The amygdala is involved in fear conditioning in people as well as rats and other animals (Olsson & Phelps, 2007; Phelps & LeDoux, 2005).

215

The Evolutionary Elements of Classical Conditioning

Evolutionary mechanisms also play an important role in classical conditioning. As you learned in the Psychology: Evolution of a Science chapter, evolution and natural selection go hand in hand with adaptiveness: Behaviors that are adaptive allow an organism to survive and thrive in its environment.

Consider this example: A psychology professor was once on a job interview in Southern California, and his hosts took him to lunch at a Middle Eastern restaurant. Suffering from a case of bad hummus, he was up all night long, and he developed a lifelong aversion to hummus. The hummus was the CS, a bacterium or some other source of toxicity was the US, and the resulting nausea was the UR. The UR (the nausea) became linked to the once-

How has cancer patients’ discomfort been eased by our understanding of food aversions?

This scenario makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. Any species that forages or consumes a variety of foods needs to develop a mechanism by which it can learn to avoid any food that once made it ill. To have adaptive value, this learning should be very rapid—

Classical conditioning of food aversions has been studied in rats, using USs such as injection or radiation that cause nausea and vomiting (Garcia & Koelling, 1966). Food aversions are relatively easy to produce in rats if the CS is an unfamiliar taste or smell, but they are difficult or impossible if the CS is a sight or sound. On the other hand, the taste and smell stimuli that produce food aversions in rats do not work with most species of birds. Birds depend primarily on visual cues for finding food and are relatively insensitive to taste and smell. However, it is relatively easy to produce a food aversion in birds using an unfamiliar visual stimulus as the CS, such as a brightly colored food (Wilcoxon, Dragoin, & Kral, 1971). Studies such as these suggest that evolution has provided each species with a kind of biological preparedness, a propensity for learning particular kinds of associations over others, so that some behaviors are relatively easy to condition in some species but not others.

biological preparedness

A propensity for learning particular kinds of associations over others.

This research had an interesting application. It led to the development of a technique for dealing with an unanticipated side effect of radiation and chemotherapy: Cancer patients who experience nausea from their treatments often develop aversions to foods they ate before the therapy. Broberg and Bernstein (1987) reasoned that if the findings with rats generalized to humans, a simple technique should minimize the negative consequences of this effect. The researchers gave the patients an unusual food (coconut-

216

SUMMARY QUIZ [7.1]

Question 7.1

| 1. | In classical conditioning, a conditioned stimulus is paired with an unconditioned stimulus to produce |

- a neutral stimulus.

- a conditioned response.

- an unconditioned response.

- another conditioned stimulus.

b.

Question 7.2

| 2. | What occurs when a conditioned stimulus is no longer paired with an unconditioned stimulus? |

- generalization

- spontaneous recovery

- extinction

- acquisition

c.

Question 7.3

| 3. | What did Watson and Rayner seek to demonstrate about behaviorism through the Little Albert experiment? |

- Conditioning involves a degree of cognition.

- Classical conditioning has an evolutionary component.

- Behaviorism alone cannot explain human behavior.

- Even sophisticated behaviors such as emotion are subject to classical conditioning.

d.

Question 7.4

| 4. | Which part of the brain is involved in the classical conditioning of fear? |

- the amygdala

- the cerebellum

- the hippocampus

- the hypothalamus

a.