7.3 Observational Learning: Look at Me

Four-

Why might a younger sibling appear to learn faster than a firstborn?

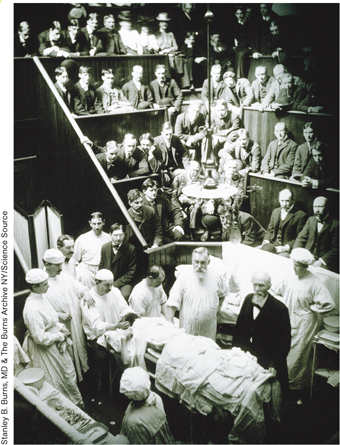

Margie’s is a case of observational learning, in which learning takes place by watching the actions of others. In all societies, appropriate social behavior is passed on from generation to generation, not only through deliberate training of the young, but also through young people observing the patterns of behaviors of their elders and each other (Flynn & Whiten, 2008). Tasks such as using chopsticks or learning to operate a TV’s remote control are more easily acquired if we watch these activities being carried out before we try ourselves. Even complex motor tasks, such as performing surgery, are learned in part through extensive observation and imitation of models. And anyone who is about to undergo surgery is grateful for observational learning. Just the thought of a generation of surgeons acquiring their surgical techniques using the trial-

observational learning

A condition in which learning takes place by watching the actions of others.

Observational Learning in Humans

In a series of studies that have become landmarks in psychology, Albert Bandura and his colleagues investigated the parameters of observational learning (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1961). The researchers escorted individual preschoolers into a play area filled with toys that 4-

What did the Bobo doll experiment show about children and aggressive behavior?

231

The children in these studies also showed that they were sensitive to the consequences of the actions they observed. When they saw the adult models being punished for behaving aggressively, the children showed considerably less aggression. When the children observed a model being rewarded and praised for aggressive behavior, they displayed an increase in aggression (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1963). The observational learning seen in Bandura’s studies has implications for social learning and cultural transmission of behaviors, norms, and values (Bandura, 1977, 1994).

Observational learning is important in many domains of everyday life. Sports provide a good example. Coaches rely on observational learning when they demonstrate critical techniques and skills to players, and athletes also have numerous opportunities to observe other athletes perform. Studies of athletes in both team and individual sports indicate that all rely heavily on observational learning to improve their performance (Wesch, Law, & Hall, 2007). But can merely observing a skill result in an improvement in performing that skill without actually practicing it? A number of studies have shown that observing someone else perform a motor task, ranging from reaching for a target to pressing a sequence of keys, can produce robust learning in the observer. In fact, observational learning sometimes results in just as much learning as practicing the task itself (Heyes & Foster, 2002; Mattar & Gribble, 2005; Vinter & Perruchet, 2002).

232

Observational Learning in Animals

Humans aren’t the only creatures capable of learning by observing. In one study, for example, pigeons watched other pigeons get reinforced for either pecking at the feeder or stepping on a bar. When placed in the box later, the pigeons tended to use whatever technique they had observed other pigeons using earlier (Zentall, Sutton, & Sherburne, 1996).

One of the most important questions about observational learning in animals concerns whether monkeys and chimpanzees can learn to use tools by observing tool use in others, the way young children can. In one of the first controlled studies to examine this issue, chimpanzees observed a model (the experimenter) use a metal bar shaped like a T to pull items of food toward him or her (Tomasello et al., 1987). Compared with a group that did not observe any tool use, these chimpanzees showed more learning when later performing the task themselves. In a later experiment, the researchers introduced a novel twist (Nagell, Olguin, & Tomasello, 1993). In one condition, a model used a rake in its normal position (with the teeth pointed to the ground) to capture a food reward, which was rather inefficient because the teeth were widely spaced and the food sometimes slipped between them. In a second condition, the model flipped over the rake so that the teeth were pointed up and the flat edge of the rake touched the ground—

The chimpanzees in these studies had been raised by their mothers in the wild. Could chimpanzees that had been raised in environments that also included human contact learn to imitate the exact actions performed by a model? The answer is a resounding yes: Chimpanzees raised in a more humanlike environment showed more specific observational learning than did those that had been reared by their mothers, and thus they performed much like human children (Tomasello, Savage-

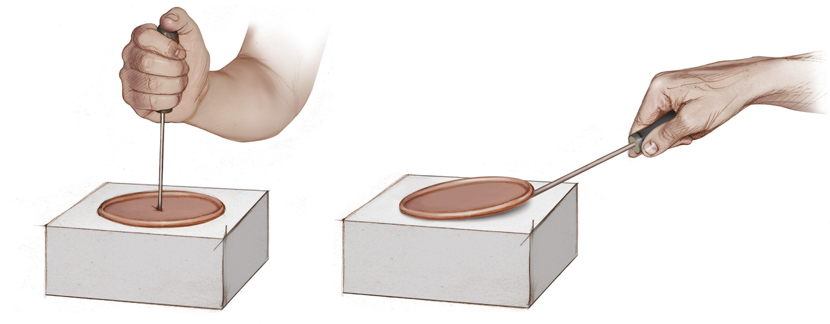

More recent research has found something similar in capuchin monkeys that are known for their tool use in the wild, such as employing branches or stone hammers to crack open nuts (Boinski, Quatrone, & Swartz, 2000; Fragaszy et al., 2004) or using stones to dig up buried roots (Moura & Lee, 2004). Fredman and Whiten (2008) studied monkeys that had been reared in the wild by their mothers or by human families in Israel as part of a project to train the monkeys to aid quadriplegics. A model demonstrated two ways of using a screwdriver to gain access to a food reward hidden in a box. Some monkeys observed the model poke through a hole in the center of the box, whereas others watched him pry open the lid at the rim of the box (see FIGURE 7.14). Both mother-

What are the cognitive differences between chimpanzees raised among humans versus raised in the wild?

Although this evidence implies that there is a cultural influence on the cognitive processes that support observational learning, the researchers noted that the effects on observational learning could be attributed to any number of influences on the human-

233

Neural Elements of Observational Learning

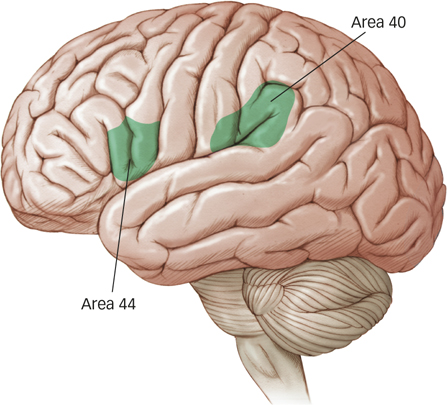

Observational learning involves a neural component as well. As you read in the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter, mirror neurons are a type of cell found in the frontal and parietal lobes of primates (including humans). Mirror neurons fire when an animal performs an action, such as when a monkey reaches for a food item (FIGURE 7.15). Mirror neurons also fire when an animal watches someone else perform the same task (Rizzolatti & Craighero, 2004). For example, monkeys’ mirror neurons fired when they observed humans grasping for a piece of food, either to eat it or to place it in a container (Fogassi et al., 2005). Although the exact functions of mirror neurons continue to be debated (Hickok, 2009), it seems likely that mirror neurons contribute to observational learning.

What do mirror neurons do?

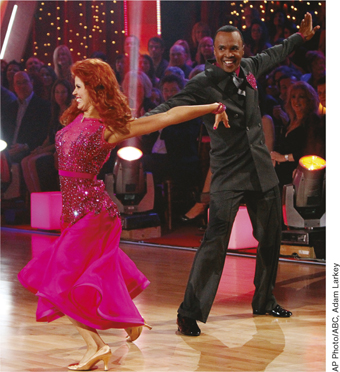

Mirror neurons exist in humans too. Studies of observational learning in healthy adults have shown that watching someone else perform an action engages some of the same brain regions that are activated when people actually perform the action themselves. In one study, participants practiced dance sequences to unfamiliar songs and watched videos containing other dance sequences accompanied by unfamiliar songs (Cross et al., 2009). The participants were then given fMRI scans while viewing videos of sequences that they had previously danced or watched, as well as videos of untrained sequences.

Results showed differences between watching the untrained sequences and watching the previously danced or watched sequences. Viewing the previously danced or watched sequences caused activity in brain regions considered to be part of the mirror neuron system. The results of a surprise dancing test given to participants after the conclusion of scanning showed that performance was better on sequences previously watched than on the untrained sequences, demonstrating significant observational learning, but it was best of all on the previously danced sequences (Cross et al., 2009). So, while watching Dancing with the Stars might indeed improve your dancing skills, practicing on the dance floor should help even more.

234

SUMMARY QUIZ [7.3]

Question 7.8

| 1. | Which is true of observational learning? |

- Although humans learn by observing others, nonhuman animals seem to lack this capability.

- If a child sees an adult engaging in a certain behavior, the child is more likely to imitate the behavior.

- Humans learn complex behaviors more readily by trial and error than by observation.

- Observational learning is limited to transmission of information between individuals of the same species.

b.

Question 7.9

| 2. | Which of the following mechanisms does NOT help form the basis of observational learning? |

- attention

- perception

- punishment

- memory

c.

Question 7.10

| 3. | Neural research indicates that observational learning is closely tied to brain areas that are involved in |

- memory.

- vision.

- action.

- emotion.

c.