8.1 Emotional Experience: The Feeling Machine

Leonardo doesn’t know what love feels like, and there’s no way to teach him because trying to describe that feeling to someone who has never experienced it is a bit like trying to describe the color green to someone who was born blind. We could tell Leonardo what causes the feeling (“It happens whenever I see Marilynn”), and we could tell him about its consequences (“I breathe hard and say goofy stuff”), but in the end, these descriptions would miss the point because the essential feature of love—

What Is Emotion

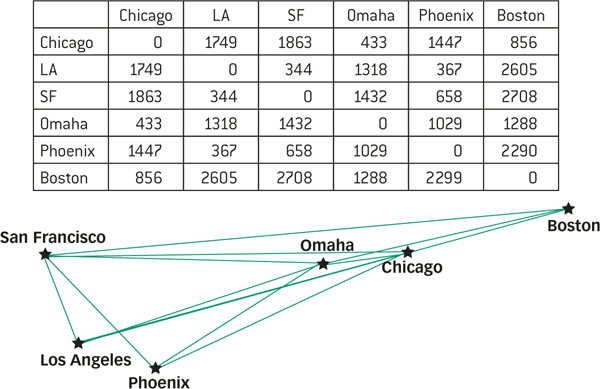

How can we study something whose defining attribute defies description? Although people can’t always say what an emotional experience feels like, they usually can say how similar or “close” one emotional experience is to another (“Love is more like happiness than like anger”). By asking people to rate the similarity of dozens of emotional experiences, psychologists have been able to use a technique known as multidimensional scaling to create a map of those experiences. The mathematics behind this technique is complex, but the logic is simple. Imagine that you had a list of the distances between a half-

What are the two dimensions on which emotions vary?

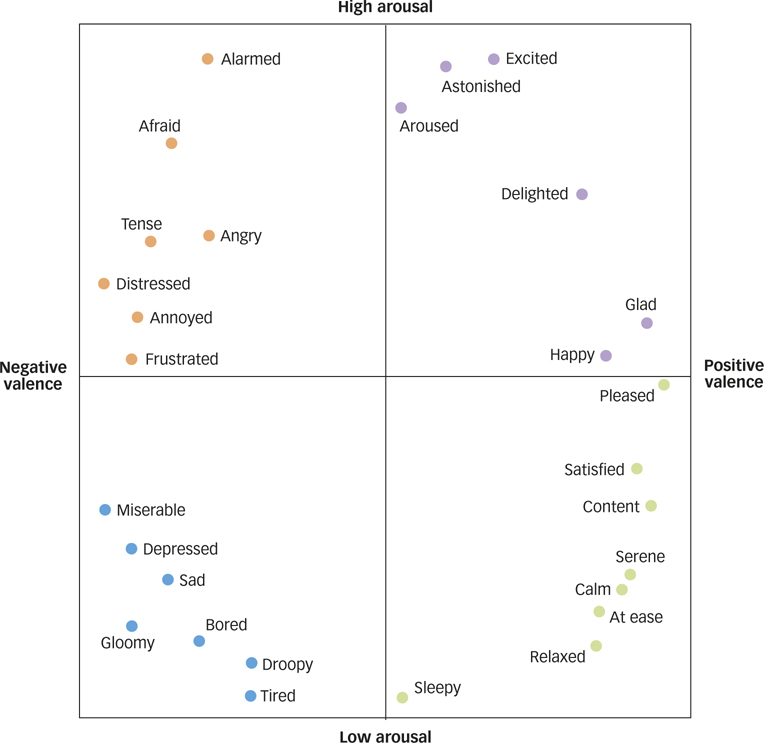

The same technique can be used to generate a map of the emotional landscape. If you had a list of the “distances” between a large number of emotional experiences (i.e., a list that showed how similar or “close” each was to the other) and tried to draw a map that reflected those distances, you would end up with a map like the one shown in FIGURE 8.2. What good would this map be? As it turns out, maps don’t just show where things are; they also reveal the dimensions on which they vary. For example, the map in FIGURE 8.2 reveals that emotional experiences vary on a dimension called valence (how positive or negative the experience is) and a dimension called arousal (how active or passive the experience is). Research shows that all emotional experiences can be described by their unique coordinates on this two-

247

This map suggests that emotional experiences have two essential properties: they feel either good or bad, and they are associated with different degrees of bodily arousal. With these two facts in mind, we can define emotion as a positive or negative experience that is associated with a particular pattern of physiological activity. As you are about to see, the first step in understanding emotion involves understanding how the “experience” part and the “physiological activity” part of this definition are related.

emotion

A positive or negative experience that is associated with a particular pattern of physiological activity.

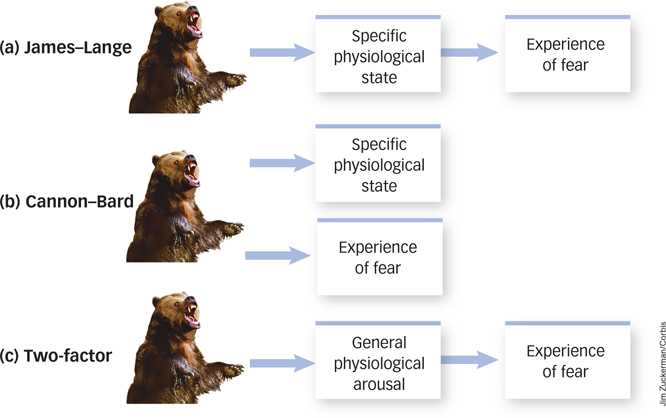

The Emotional Body

You probably think that if you walked into your kitchen right now and saw a bear nosing through the cupboards, you would feel fear, your heart would start to pound, and the muscles in your legs would contract as you prepared to run. But in the late 19th century, William James suggested that the events might actually happen in the opposite order: First you’d see the bear, then your heart would start pounding and your leg muscles would contract, and then you would experience fear, which is simply your experience of your body’s response to the sight of the bear. Psychologist Carl Lange suggested something similar at about the same time, so the idea is now known as the James-Lange theory of emotion, which states that stimuli trigger activity in the body, which in turn produces emotional experiences in the brain. According to this theory, emotional experience is the consequence—

James–Lange theory

The theory that a stimulus triggers activity in the body, which in turn produces an emotional experience in the brain.

248

James’s former student, Walter Cannon, didn’t like this idea very much, and so together with his student, Philip Bard, he proposed an alternative. The Cannon-Bard theory of emotion suggests that stimuli simultaneously trigger activity in the body and emotional experience in the brain (Bard, 1934; Cannon, 1929). Cannon and Bard claimed that their theory was better than the James–

Cannon–Bard theory

The theory that a stimulus simultaneously triggers activity in the body and emotional experience in the brain.

These are all good questions, and about 30 years after Cannon and Bard asked them, psychologists Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer supplied some answers (Schachter & Singer, 1962). Schachter and Singer thought that James and Lange were right to equate emotion with the perception of one’s bodily reactions, and that Cannon and Bard were right to note that there are not nearly enough distinct bodily reactions to account for the wide variety of emotions that human beings can experience. Their two-factor theory of emotion suggested that emotions are based on inferences about the causes of general physiological arousal (see FIGURE 8.3). According to this theory, when you see a bear in your kitchen, your heart begins to pound. Your brain notices both the pounding and the bear, puts two and two together, and interprets your bodily arousal as fear. According to the two-

two-factor theory

The theory that emotions are based on inferences about the causes of physiological arousal.

249

What is the two-

How has the two-

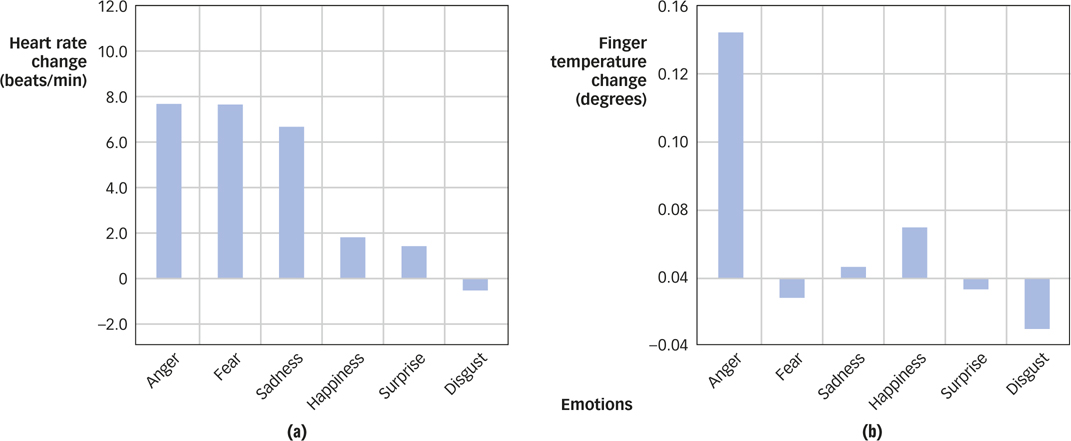

But research has not been so kind to the model’s claim that all emotional experiences are merely different interpretations of the same kind of bodily arousal. For example, researchers measured participants’ physiological reactions as they experienced six different emotions and found that anger, fear, and sadness each produced a higher heart rate than disgust, and that anger produced a larger increase in finger temperature than did fear (Ekman, Levenson, & Friesen, 1983; see FIGURE 8.4). These findings have been replicated across different age groups, professions, genders, and cultures (Levenson, Ekman, & Friesen, 1990; Levenson et al., 1991, 1992). In fact, some physiological responses seem unique to a single emotion. For example, a blush is the result of increased blood volume in the subcutaneous capillaries in the face, neck, and chest, and research suggests that people blush when they feel embarrassment but not when they feel any other emotion (Leary et al., 1992). Similarly, certain patterns of activity in the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system (which is responsible for slowing and calming rather than speeding and exciting) seem uniquely related to prosocial emotions such as compassion (Oately, Keltner, & Jenkins, 2006).

250

Where does all this leave us? James and Lange were right when they suggested that the patterns of physiological response are not the same for all emotions. But Cannon and Bard were also right when they suggested that people are not perfectly sensitive to these patterns of response, which is why people must sometimes make inferences about what they are feeling. Our bodily activity and our mental activity are, it seems, both the causes and the consequences of our emotional experience.

The Emotional Brain

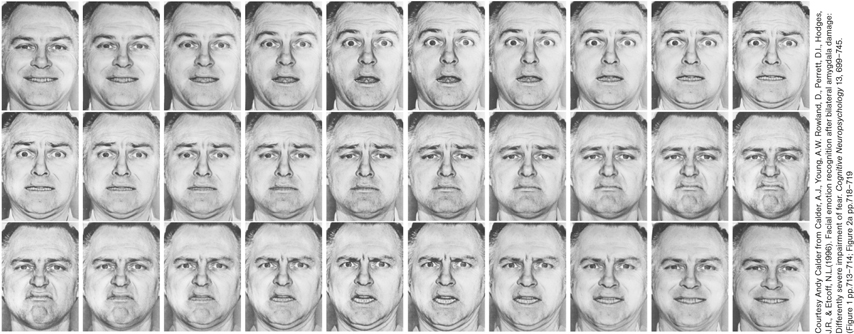

In the late 1930s, psychologist Heinrich Klüver and physician Paul Bucy made an accidental discovery. A few days after performing brain surgery on a monkey named Aurora, they noticed that she was acting strangely. First, Aurora would eat just about anything and have sex with just about anyone—

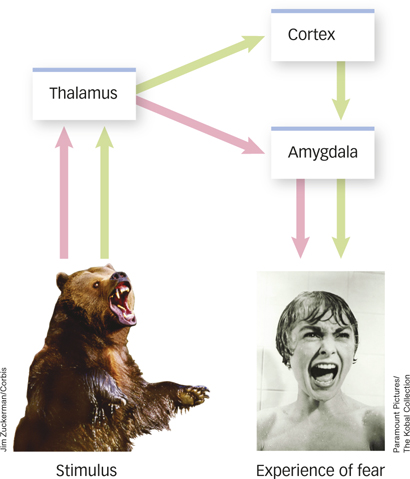

What exactly does the amygdala do? Is it some sort of “fear center”? Not exactly (Cunningham & Brosch, 2012). Before an animal can feel fear, its brain must first decide that there is something to be afraid of. This decision is called an appraisal, which is an evaluation of the emotion-

Paramount Pictures/The Kobal Collection

appraisal

An evaluation of the emotion-

251

The cortex takes longer to process its information than the amygdala does. But when it’s finished, it sends a signal to the amygdala telling it either to maintain the state of fear (“We’ve now analyzed all the data up here, and sure enough, that thing is a bear!”) or to decrease it (“Relax, it’s just some guy in a bear costume”). In a sense, the amygdala presses the emotional gas pedal and the cortex may or may not hit the brakes. When experimental subjects are instructed to experience emotions such as sadness, fear, and anger, they show increased activity in the amygdala and decreased activity in the cortex (Damasio et al., 2000), but when they are asked to inhibit these emotions, they show increased cortical activity and decreased amygdala activity (Ochsner et al., 2002). That’s why adults with cortical damage and children (whose cortices are not well developed) have difficulty inhibiting their emotions (Stuss & Benson, 1986).

The conclusion is clear: emotion is part of a primitive brain system that prepares us to react rapidly and on the basis of little information to things that are relevant to our survival and well-

How do the amygdala and the cortex interact to produce emotion?

The Regulation of Emotion

It will not surprise you to learn that people would usually rather feel good than bad. Emotion regulation refers to the strategies people use to influence their own emotional experience. Ninety percent of people report attempting to regulate their emotional experience at least once a day (Gross, 1998), and describe more than a thousand different strategies for doing so (Parkinson & Totterdell, 1999). Some of these are behavioral strategies (e.g., avoiding situations that trigger unwanted emotions), some are cognitive strategies (e.g., recruiting memories that trigger the desired emotion; Webb, Miles, & Sheeran, 2012), and research shows that people don’t always know which of these strategies is most effective. For example, people tend to think that suppression, which involves inhibiting the outward signs of an emotion, is generally an effective strategy, but by and large, it isn’t (Gross, 2002). Conversely, people tend to think that affect labeling, which involves putting one’s feelings into words, will have little impact on their emotions, when in fact, it is actually an effective way to reduce the intensity of an emotional state (Lieberman et al., 2011).

emotion regulation

The strategies people use to influence their own emotional experience.

252

One of the best strategies for emotion regulation is reappraisal, which involves changing one’s emotional experience by changing the way one thinks about the emotion-

reappraisal

Changing one’s emotional experience by changing the way one thinks about the emotion-

How, and how well, does reappraisal work?

When it comes to reappraisal, some people do it better than others (Malooly, Genet, & Siemer, 2013), and those who do it best tend to be the most mentally and physically healthy (Davidson, Putnam, & Larson, 2000; Gross & Munoz, 1995). Indeed, as you will learn in the Stress and Health chapter, therapists often attempt to alleviate depression and distress by teaching people how to reappraise key events in their lives (Jamieson, Mendes, & Nock, 2013). About two thousand years ago, the Roman philosopher and emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote: “If you are distressed by anything external, the pain is not due to the thing itself, but to your estimate of it; and this you have the power to revoke at any moment.” Modern science suggests that he was right.

SUMMARY QUIZ [8.1]

Question 8.1

| 1. | Emotions can be described by their location on the two dimensions of |

- motivation and scaling.

- arousal and valence.

- stimulus and reaction.

- pain and pleasure.

b.

Question 8.2

| 2. | Which theorists claimed that a stimulus simultaneously causes both an emotional experience and a physiological reaction? |

- Cannon and Bard

- James and Lange

- Schacter and Singer

- Klüver and Bucy

a.

Question 8.3

| 3. | Which brain structure is most directly involved in the rapid appraisal of a stimulus as good or bad? |

- the cortex

- the hypothalamus

- the amygdala

- the thalamus

c.

253

Question 8.4

| 4. | The act of changing an emotional experience by changing the meaning of the emotion- |

- deactivation

- appraisal

- valence

- reappraisal

d.