8.2 Emotional Communication: Msgs w/o Wrds

Leonardo the robot may not be able to feel, but he sure can smile. And wink. And nod. Indeed, one of the reasons why people who interact with Leonardo find it so hard to think of him as a machine is that Leonardo expresses emotions that he doesn’t actually have. An emotional expression is an observable sign of an emotional state, and both robots and people are programmed to make them.

emotional expression

An observable sign of an emotional state.

How do our bodies express our inner states?

Emotions can be expressed by the tone of our speech, the direction of our gaze, and even the rhythm of our gait. But no part of the body is more emotionally expressive than the face. The muscles of the human face can make 46 distinct patterns known as “action units” (Ekman, 1965; Ekman & Friesen, 1971), and combinations of different action units are reliably related to specific emotional states (Davidson et al., 1990). For example, when people feel happy, their zygomatic major muscles pull up their lip corners while their obicularis oculi muscles crinkle the outside edges of their eyes. Psychologists refer to the resulting expression as “Action Units 6+12” but the rest of the world just calls it smiling.

Communicative Expression

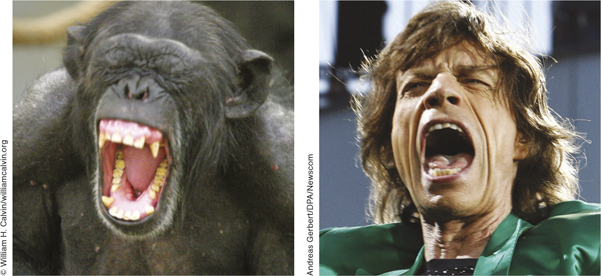

Why do faces express emotion? In 1872, Charles Darwin published The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, in which he speculated about the evolutionary significance of emotional expression. Darwin noticed that human and nonhuman animals share certain facial and postural expressions, and he suggested that these expressions were meant to communicate information about internal states. It’s not hard to see how such communications could be useful (Shariff & Tracy, 2011). For example, if a dominant animal can bare its teeth and communicate the message, “I am angry at you,” and if a subordinate animal can lower its head and communicate the message, “I am afraid of you,” then the two can establish a pecking order without actually spilling any blood. In this sense, emotional expressions are a bit like the words of a nonverbal language.

254

Andreas Gerbert/DPA/Newscom

The Universality of Expression

What evidence suggests that facial expressions are universal?

Of course, a language only works if everybody speaks the same one, which is why Darwin advanced the universality hypothesis, which suggests that all human beings naturally make and understand the same emotional expressions. There is some evidence for this hypothesis. For example, people who have never seen a human face make the same facial expressions as those who have. Congenitally blind people smile when they are happy (Galati, Scherer, & Ricci-

universality hypothesis

Emotional expressions have the same meaning for everyone.

The Cause and Effect of Expression

It seems obvious that our emotional experiences cause our emotional expressions. What’s less obvious is that it also works the other way around. The facial feedback hypothesis (Adelmann & Zajonc, 1989; Izard, 1971; Tomkins, 1981) suggests that emotional expressions can cause emotional experiences. And they can! People feel happier when they are asked to make the sound of a long e or to hold a pencil in their teeth (both of which cause contraction of the zygomatic major muscle) than when they are asked to make the sound of a long u or to hold a pencil in their lips (Strack, Martin, & Stepper, 1988; Zajonc, 1989; see FIGURE 8.7). Similarly, when people are instructed to arch their brows, they find facts more surprising; and when instructed to wrinkle their noses, they find odors less pleasant (Lewis, 2012). These things happen because facial expressions and emotional states become strongly associated with each other over time, and eventually, each can bring about the other. These effects are not limited to the face. For example, people feel more assertive when instructed to make a fist (Schubert & Koole, 2009) and rate others as more hostile when instructed to extend their middle fingers (Chandler & Schwarz, 2009).

facial feedback hypothesis

Emotional expressions can cause the emotional experiences they signify.

Why do emotional expressions cause emotional experience?

255

Hot Science: The Body of Evidence

The Body of Evidence

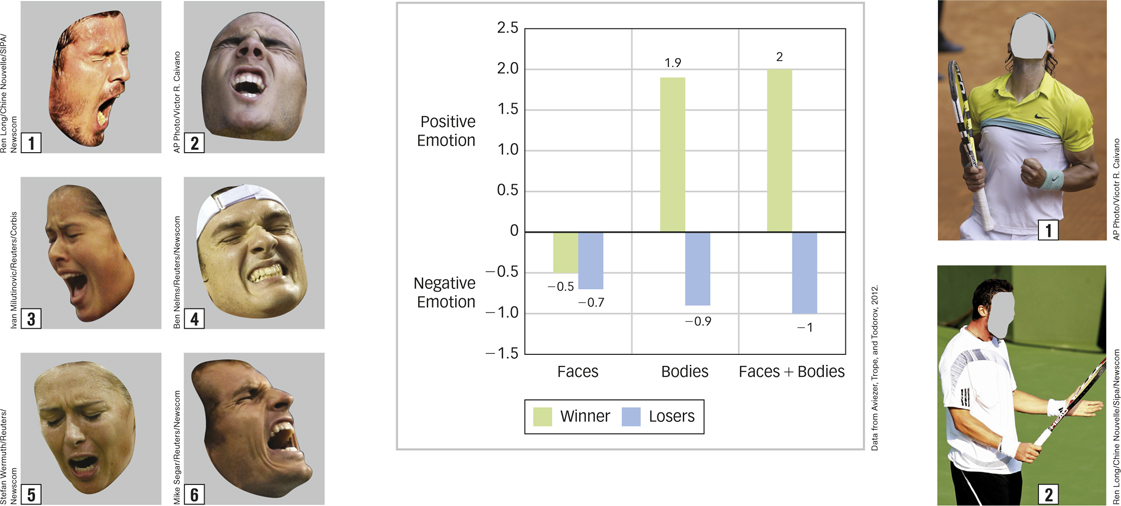

What can you tell from a face alone? Maybe less than you realize. Aviezer, Trope, and Todorov (2012) showed participants faces taken from pictures of tennis players who had either just won a point (Faces 2, 3, and 5 in the figure shown here) or lost a point (Faces 1, 4, and 6), and the researchers asked them to guess whether the athlete was experiencing a positive or negative emotion. As the leftmost bars of the graph show, participants couldn’t tell. They guessed that the “winning faces” and the “losing faces” were experiencing equal amounts of somewhat negative emotion.

Next, the researchers showed a new group of participants bodies (without faces) taken from pictures of tennis players who had either just won a point (Body 1 in the figure) or lost a point (Body 2), and the researchers asked them to make the same judgment. As the middle bars show, participants were quite good at this. Participants guessed that “winning bodies” were experiencing positive emotions and that “losing bodies” were experiencing negative emotions.

Finally, the researchers showed a new group of participants the athletes’ bodies and faces together. As the rightmost bars show, participants’ ratings of the body–

It seems that facial expressions of emotion are more ambiguous than most of us realize. When we see people expressing anger, fear, or joy, we are using information from their bodies, their voices, and their physical and social contexts to figure out what they are feeling. Yet, we mistakenly believe that we are getting most of our information from their facial expression.

The moral of the story? Next time you want to know how a losing athlete feels, concentrate more on defeat than deface. (Sorry.)

AP Photo/Victor R. Caivano

Ivan Milutinovic/Reuters/Corbis

Ben Nelms/Reuters/Newscom

Stefan Wermuth/Reuters/Newscom

Mike Segar/Reuters/Newscom

Data from Aviezer, Trope, and Todorov, 2012.

AP Photo/Vicotr R. Caivano

Ren Long/Chine Nouvelle/Sipa/Newscom

256

The fact that emotional expressions can cause the emotional experiences they signify may help explain why people are generally so good at recognizing the emotional expressions of others. Many studies show that people unconsciously mimic other people’s body postures and facial expressions (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999; Dimberg, 1982). When we see someone smile (or even when we read about someone smiling), our zygomatic major muscle contracts ever so slightly—

Deceptive Expression

Our emotional expressions can communicate our feelings truthfully—

display rule

A norm for the appropriate expression of emotion.

People in different cultures have different display rules. For example, in one study, Japanese and American college students watched an unpleasant video of car accidents and amputations (Ekman, 1972; Friesen, 1972). When the students didn’t know that the experimenters were observing them, Japanese and American students made similar expressions of disgust, but when they realized that they were being observed, the Japanese students (but not the American students) masked their disgust with pleasant expressions. In many Asian countries, it is considered rude to display negative emotions in the presence of a respected person, and so citizens of these countries tend to neutralize their expressions. The fact that different cultures have different display rules may help explain why we are good at recognizing the facial expressions of people from other cultures but really really really good at recognizing the facial expressions of people from our own cultures (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002).

How does emotional expression differ across cultures?

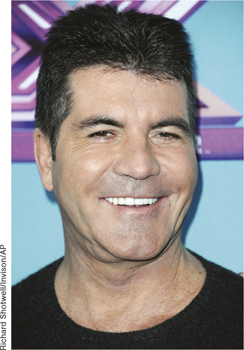

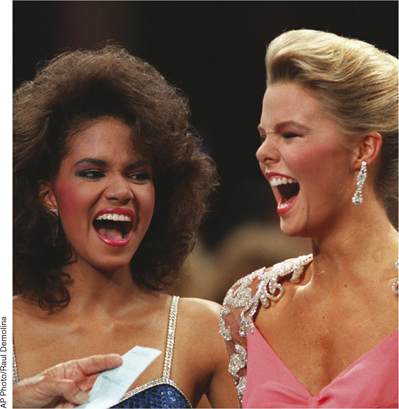

Like most rules, display rules are sometimes difficult to obey. Anyone who has ever watched the loser of a beauty pageant congratulate the winner knows that no matter how hard they try, people can’t always hide their emotional states. Even when people smile bravely to mask their disappointment, for example, their faces tend to express small bursts of disappointment that last just 1/25 to 1/5 of a second – so fast that they are almost impossible to detect with the naked eye (Porter & ten Brinke, 2008). In addition, some facial muscles resist conscious control. For example, people can easily control the zygomatic major muscle that raises the corners of their mouths to make a smile, but most can’t easily control the obicularis oculi muscle that crinkles the corners of their eyes. This fact allows trained observers to tell when a smile is or isn’t genuine (see FIGURE 8.8).

257

Our faces don’t always tell the truth–

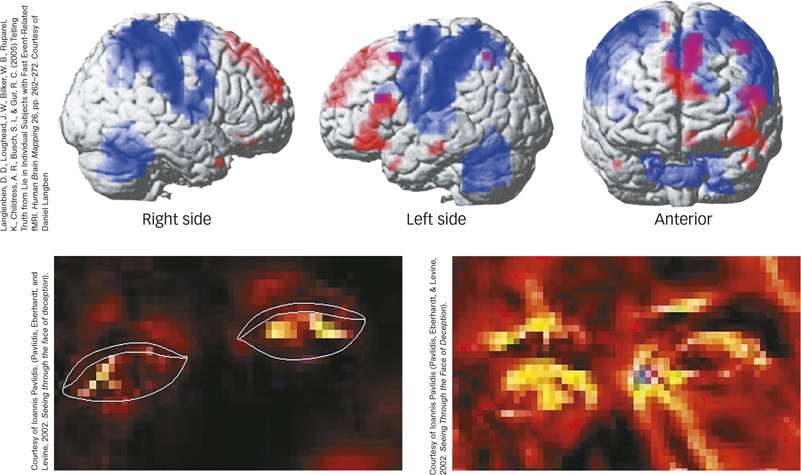

Given the reliable differences between liars and truth-

When people can’t do something well, such as adding large numbers or moving large rocks, they typically turn the job over to a machine (see FIGURE 8.9). Can machines detect lies better than we can? The answer is yes, though that’s not saying very much. The most widely used lie detection machine is the polygraph, which measures the physiological responses that are associated with stress, which people often feel when they are afraid of being caught in a lie. A polygraph can detect lies at a rate that is better than chance, but its error rate is still remarkably high. The fact is that neither people nor machines are particularly good at lie detection, which is why lying remains such a popular sport among humans.

Courtesy of Ioannis Pavlidis. (Pavlidis, Eberhardt, and Levine, 2002. Seeing through the face of deception).

Courtesy of Ioannis Pavlidis (Pavlidis, Eberhardt, & Levine, 2002. Seeing Through the Face of Deception).

258

SUMMARY QUIZ [8.2]

Question 8.5

| 1. | Which of the following does NOT provide any support for the universality hypothesis? |

- Congenitally blind people make the facial expressions associated with the basic emotions.

- Infants only days old react to bitter tastes with expressions of disgust.

- Robots have been engineered to exhibit emotional expressions.

- Researchers have discovered that isolated people living a Stone Age existence with little contact with the outside world recognize the emotional expressions of Westerners.

c.

Question 8.6

| 2. | _________ is the idea that emotional expressions can cause emotional experiences. |

- A display rule

- Expressional deception

- The universality hypothesis

- The facial feedback hypothesis

d.

Question 8.7

| 3. | Which of the following statements is inaccurate? |

- Certain facial muscles are reliably engaged by sincere facial expressions.

- Even when people smile bravely to mask disappointment, their faces tend to express small bursts of disappointment.

- Studies show that human lie detection ability is extremely good.

- Polygraph machines detect lies at a rate better than chance, but their error rate is still quite high.

c.