9.4 Intelligence

Remember Christopher, the boy who could learn languages but not tic-

intelligence

The ability to direct one’s thinking, adapt to one’s circumstances, and learn from one’s experiences.

The Intelligence Quotient

Archives of the History of American Psychology, The University of Akron

Few things are more dangerous than a man with a mission. In the 1920s, psychologist Henry Goddard administered intelligence tests to arriving immigrants at Ellis Island and concluded that the overwhelming majority of Jews, Hungarians, Italians, and Russians were “feebleminded.” Goddard also used his tests to identify feebleminded American families (whom, he claimed, were largely responsible for the nation’s social problems) and suggested that the government should segregate them in isolated colonies and “take away from these people the power of procreation” (Goddard, 1913, p. 107). The United States subsequently passed laws restricting the immigration of people from southern and eastern Europe, and 27 states passed laws requiring the sterilization of “mental defectives.”

294

Why were intelligence tests originally developed?

From Goddard’s day to our own, intelligence tests have been used to rationalize prejudice and discrimination against people of different races, religions, and nationalities. This is especially ironic because such tests were originally developed for the most noble of purposes: to help underprivileged children succeed in school. At the end of the 19th century, France instituted a sweeping set of education reforms that made a primary school education available to children of every social class, and suddenly French classrooms were filled with a diverse mix of children who differed dramatically in their readiness to learn. The French government called on Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon to create a test that would allow educators to develop remedial programs for those children who lagged behind their peers (Siegler, 1992). “Before these children could be educated,” Binet (1909) wrote, “they had to be selected. How could this be done?”

Binet and Simon set out to develop an objective test that would provide an unbiased measure of a child’s ability. They began, sensibly enough, by looking for tasks that the best students in a class could perform and that the worst students could not—

How do the two kinds of intelligence quotients differ?

This simple idea became the basis for what is now known as the intelligence quotient or IQ score. There are two ways to compute an IQ score. One is the ratio IQ, which is a statistic obtained by dividing a person’s mental age by the person’s physical age and then multiplying the quotient by 100. According to this formula, a 10-

ratio IQ

A statistic obtained by dividing a person’s mental age by the person’s physical age and then multiplying the quotient by 100 (see deviation IQ).

deviation IQ

A statistic obtained by dividing a person’s test score by the average test score of people in the same age group and then multiplying the quotient by 100 (see ratio IQ).

295

The Intelligence Test

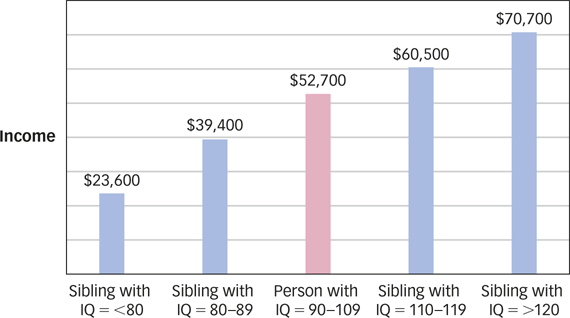

The most widely used modern intelligence test is the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), named after its originator, psychologist David Wechsler. Like Binet and Simon’s original test, it measures intelligence by asking respondents to solve problems, to articulate the meaning of words, to recall general knowledge, to explain practical actions in everyday life, and so forth. Some sample problems from the WAIS are shown in TABLE 9.2. Decades of research show that a person’s performance on tests like the WAIS predict a wide variety of important life outcomes, including health, educational level, and income (Deary, Batty, & Gale, 2008; Deary et al., 2008; Der, Batty, & Deary, 2009; Gottfredson & Deary, 2004; Leon et al., 2009; Richards et al., 2009; Rushton & Templer, 2009; Whalley & Deary, 2001). One study compared siblings who had significantly different IQs and found that the less intelligent sibling earned roughly half of what the more intelligent sibling earned over the course of their lifetimes (Murray, 2002; see FIGURE 9.11). Perhaps that’s because intelligent people perform better at their jobs (Hunter & Hunter, 1984; see the Real World box).

|

WAIS- |

Core Subtest |

Questions and Tasks |

|---|---|---|

|

Verbal Comprehension Test |

Vocabulary |

The test taker is asked to tell the examiner what certain words mean. For example: chair (easy), hesitant (medium), and presumptuous (hard). |

|

|

Similarities |

The test taker is asked what 19 pairs of words have in common. For example: In what way are an apple and a pear alike? In what way are a painting and a symphony alike? |

|

|

Information |

The test taker is asked several general knowledge questions. These cover people, places, and events. For example: How many days are in a week? What is the capital of France? Name three oceans. Who wrote The Inferno? |

|

Perceptual Reasoning Test |

Block Design |

The test taker is shown 2- |

|

|

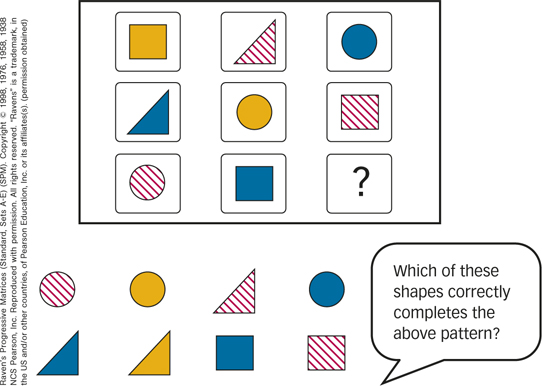

Matrix Reasoning |

The test taker is asked to add a missing element to a pattern so that it progresses logically. For example: Which of the four symbols at the bottom goes in the empty cell of the table?

|

|

|

Visual Puzzles |

The test taker is asked to complete visual puzzles like this one: “Which three of these pictures go together to make this puzzle?” |

|

Working Memory Test |

Digit Span |

The test taker is asked to repeat a sequence of numbers. Sequences run from two to nine numbers in length. In the second part of this test, the sequences must be repeated in reversed order. An easy example is to repeat 3- |

|

|

Arithmetic |

The test taker is asked to solve arithmetic problems, progressing from easy to difficult ones. |

|

Processing Speed Test |

Symbol Search |

The test taker is asked to indicate whether one of a pair of abstract symbols is contained in a list of abstract symbols. There are many of these lists, and the test taker does as many as he or she can in 2 minutes. |

|

|

Coding |

The test taker is asked to write down the number that corresponds to a code for a given symbol (e.g., a cross, a circle, and an upside- |

296

The Real World: Look Smart

Look Smart

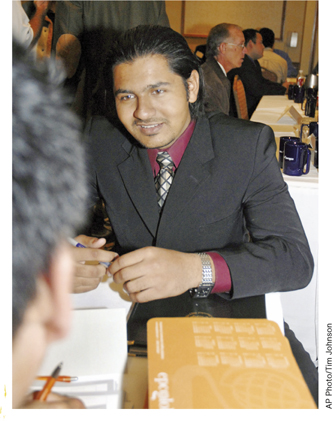

Your interview is in 30 minutes. You’ve checked your hair twice, eaten your weight in breath mints, combed your résumé for typos, and rehearsed your answers to all the standard questions. Now you have to dazzle the interviewer with your intelligence whether you’ve got it or not. Because intelligence is one of the most valued of all human traits, we are often in the business of trying to make others think we’re smart regardless of whether that’s true. So we make clever jokes and drop the names of some of the longer books we’ve read in the hope that prospective employers, prospective dates, prospective customers, and prospective in-

But are we doing the right things, and if so, are we getting the credit we deserve? Research shows that ordinary people are, in fact, reasonably good judges of other people’s intelligence (Borkenau & Liebler, 1995). For example, observers can look at a pair of photographs and reliably determine which of the two people in them is smarter (Zebrowitz et al., 2002). When observers watch 1-

People base their judgments of intelligence on a wide range of cues, from physical features (being tall and attractive) to dress (being well groomed and wearing glasses) to behavior (walking and talking quickly). And yet, none of these cues is actually a reliable indicator of a person’s intelligence. The reason why people are such good judges of intelligence is that in addition to all these useless cues, they also take into account one very useful cue: eye gaze. As it turns out, intelligent people hold the gaze of their conversation partners both when they are speaking and when they are listening, and observers know this, which is what enables them to estimate a person’s intelligence accurately, despite their mythical beliefs about the informational value of spectacles and neckties (Murphy et al., 2003). All of this is especially true when the observers are women (who tend to be better judges of intelligence) and the people being observed are men (whose intelligence tends to be easier to judge).

The bottom line? Breath mints are fine and a little gel on the cowlick certainly can’t hurt, but when you get to the interview, don’t forget to stare.

A Hierarchy of Abilities

During the 1990s, Michael Jordan won the National Basketball Association’s Most Valuable Player award five times, led the Chicago Bulls to six league championships, and had the highest regular season scoring average in the history of the game. ESPN named him the greatest athlete of the century. So when Jordan quit professional basketball in 1993 to join professional baseball, he was as surprised as anyone else to find that he … well, sucked. One of his teammates lamented that Jordan “couldn’t hit a curveball with an ironing board,” and a major-

297

Michael Jordan’s brilliance on the basketball court and his mediocrity on the baseball field proved beyond all doubt that these two sports require different abilities that are not necessarily possessed by the same individual. But if basketball and baseball require different abilities, then what does it mean to say that someone is the greatest athlete of the century? Is athleticism a meaningless word? The science of intelligence has grappled with a similar question for more than a century. As we have seen, intelligence test scores predict important outcomes—

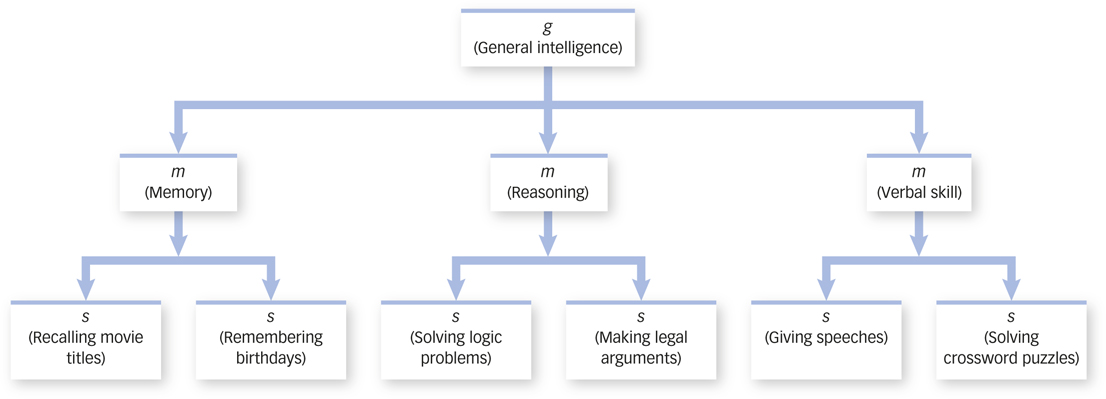

To investigate this question, Charles Spearman (a student of Wilhelm Wundt, whom you met in the Psychology: Evolution of a Science chapter), measured how well school-

two-factor theory of intelligence

Spearman’s theory suggesting that every task requires a combination of a general ability (which he called g) and skills that are specific to the task (which he called s).

As sensible as Spearman’s conclusions were, not everyone agreed with them. Louis Thurstone (1938) noticed that although childrens’ scores on different tests were indeed positively correlated with one another, scores on one kind of verbal test were more highly correlated with scores on another verbal test than they were with scores on other kinds of tests. Thurstone took this “clustering of correlations” to mean that there was actually no such thing as g and that there were, instead, a few stable and independent mental abilities such as perceptual ability, verbal ability, and numerical ability, which he called the primary mental abilities. In essence, Thurstone argued that just as we have games called baseball and basketball but no game called athletics, so we have abilities such as verbal ability and perceptual ability but no general ability called intelligence. TABLE 9.3 shows the primary mental abilities that Thurstone identified.

|

Primary Mental Ability |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Verbal Word Fluency |

Ability to solve anagrams and to find rhymes, etc. |

|

Verbal Comprehension |

Ability to understand words and sentences |

|

Numerical Ability |

Ability to make mental and other numerical computations |

|

Spatial Visualization |

Ability to visualize a complex shape in various orientations |

|

Associative Memory |

Ability to recall verbal material, learn pairs of unrelated words, etc. |

|

Perceptual Speed |

Ability to detect visual details quickly |

|

Reasoning |

Ability to induce a general rule from a few instances |

How was the debate between Spearman and Thurstone resolved?

The debate among Spearman, Thurstone, and other intelligence researchers raged for half a century as psychologists argued about the existence of g. But in the 1980s, new mathematical techniques brought the debate to a quiet close by revealing that Spearman and Thurstone had each been right in his own way. We now know that most intelligence test data are best described by a three-

So what are these middle level abilities, and how many are there? Psychologist John Carroll (1993) analyzed intelligence test scores from nearly 500 studies conducted over a half century, and he concluded that there are eight independent middle-

fluid intelligence

The ability to see abstract relationships and draw logical inferences.

crystallized intelligence

The ability to retain and use knowledge that was acquired through experience.

298

So was that the end of the debate? Not exactly, because some psychologists have argued that there are kinds of intelligence that traditional tests simply do not measure. For example, Robert Sternberg (1999) distinguishes between analytic intelligence (which is the ability to identify and define problems and to find strategies for solving them), practical intelligence (which is the ability to apply and implement these solutions in everyday settings), and creative intelligence (which is the ability to generate solutions that other people do not). According to Sternberg, standard intelligence tests measure analytic intelligence by giving people clearly defined problems that have one right answer. But everyday life confronts people with situations in which they must formulate the problem, find the information needed to solve it, and then choose among multiple acceptable solutions. These situations require practical and creative intelligence.

299

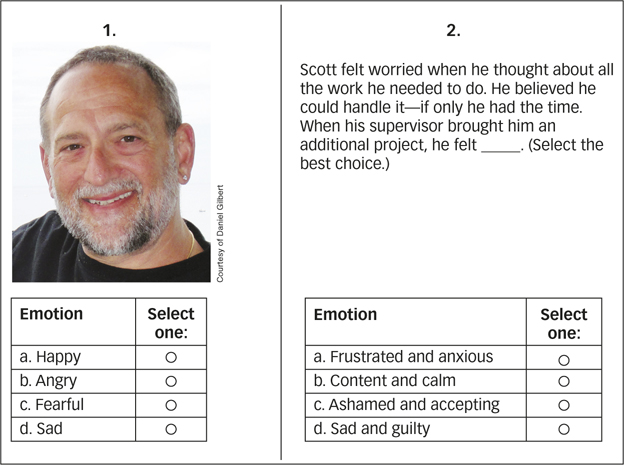

What skills are particularly strong in emotionally intelligent people?

Another kind of intelligence that standard tests don’t measure is emotional intelligence, which is the ability to reason about emotions and to use emotions to enhance reasoning (Mayer, Roberts, & Barsade, 2008; Salovey & Grewal, 2005). Emotionally intelligent people know what kinds of emotions a particular event will trigger; they can identify, describe, and manage their emotions; and they can identify other people’s emotions from facial expressions and tones of voice. Emotionally intelligent people have better social skills and more friends (Eisenberg et al., 2000; Mestre et al., 2006; Schultz, Izard, & Bear, 2004), they are judged to be more competent in their interactions (Brackett et al., 2006), and they have better romantic relationships (Brackett, Warner, & Bosco, 2005). Given all this, it isn’t surprising that emotionally intelligent people tend to be happier (Brackett & Mayer, 2003; Brackett et al., 2006) and more satisfied with their lives (Ciarrochi, Chan, & Caputi, 2000; Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 1999).

emotional intelligence

The ability to reason about emotions and to use emotions to enhance reasoning.

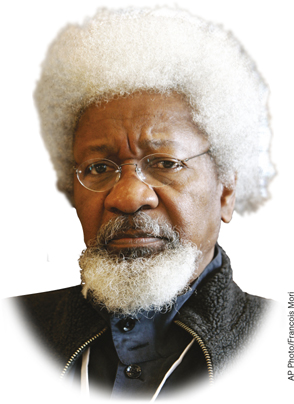

How does the concept of intelligence differ across cultures?

Not only are there different kinds of intelligence, but the concept itself seems to differ across cultures. For instance, Westerners regard people as intelligent when they speak quickly and often, but Africans regard people as intelligent when they are deliberate and quiet (Irvine, 1978). The Confucian tradition emphasizes the ability to behave properly, the Taoist tradition emphasizes humility and self-

300

SUMMARY QUIZ [9.4]

Question 9.11

| 1. | Which of the following abilities is not an accepted feature of intelligence? |

- the ability to direct one’s thinking

- the ability to adapt to one’s circumstances

- the ability to care for oneself

- the ability to learn from one’s experiences

c.

Question 9.12

| 2. | Intelligence tests |

- were first developed to help children who lagged behind their peers.

- were developed to measure aptitude rather than educational achievement.

- have been used for detestable ends.

- all of the above

d.

Question 9.13

| 3. | People who score well on one test of mental ability usually score well on others, suggesting that |

- tests of mental ability are perfectly correlated.

- intelligence cannot be measured meaningfully.

- there is a general ability called intelligence.

- intelligence is genetic.

c.

Question 9.14

| 4. | The two- |

- factor analysis.

- specific abilities.

- primary mental abilities.

- creative intelligence.

b.

Question 9.15

| 5. | Most scientists now believe that intelligence is best described |

- as a set of group factors.

- by a two-

factor framework. - as a single, general ability.

- by a three-

level hierarchy.

d.