9.5 Where Does Intelligence Come From?

No one is born knowing calculus, and no one has to be taught how to yawn. Some things are learned, others are not. But almost all of the really interesting things about people are a joint product of the innate characteristics with which their genes have endowed them and of the experiences they have in the world. Intelligence is one of those really interesting things that is influenced both by nature and by nurture. Let’s start by examining nature’s influence.

Genetic Influences on Intelligence

The fact that intelligence appears to “run in families” isn’t very good evidence of nature’s influence. After all, brothers and sisters share genes, but they share many other things as well. They typically grow up in the same house, go to the same schools, read many of the same books, and have many of the same friends. Members of a family may have similar levels of intelligence because they share genes, environments, or both. To separate the influence of genes and environments, we need to examine the intelligence test scores of people who share genes but not environments (e.g., biological siblings who are separated at birth and raised by different families), people who share environments but not genes (e.g., adopted siblings who are raised together), and people who share both (e.g., biological siblings who are raised together).

301

To do this, it helps to understand that there are several kinds of siblings with different degrees of genetic relatedness. When siblings have the same biological parents but different birthdays, they share on average 50% of their genes. Twins have the same parents and the same birthdays, but there are two kinds of twins. Fraternal twins (or dizygotic twins) develop from two different eggs that were fertilized by two different sperm, and although they happen to have the same parents and birthdays, they are merely siblings who shared a womb, so like any siblings, they share on average 50% of their genes. Identical twins (or monozygotic twins) are special because they develop from the splitting of a single egg that was fertilized by a single sperm, so unlike any other siblings, they are genetic duplicates of each other who share 100% of their genes.

fraternal twins (or dizygotic twins)

Twins who develop from two different eggs that were fertilized by two different sperm (see identical twins).

identical twins (or monozygotic twins)

Twins who develop from the splitting of a single egg that was fertilized by a single sperm (see fraternal twins).

These different degrees of genetic relatedness allow psychologists to assess the influence that genes have on intelligence. Studies show that the IQs of identical twins are very strongly correlated when the twins are raised in the same household, but they are also strongly correlated when the twins are separated at birth and raised in different households. In fact, identical twins who are raised apart have more similar IQs than do fraternal twins who are raised together. What this means is that people who share all their genes have similar IQs regardless of whether they share their environments. By comparison, the intelligence test scores of unrelated people raised in the same household (e.g., two siblings, one or both of whom were adopted) are correlated only modestly (Bouchard & McGue, 2003). These patterns suggest that genes play an important role in determining intelligence and this shouldn’t surprise us. Intelligence is, in part, a function of how the brain works, and given that brains are designed by genes, it would be quite remarkable if genes didn’t play some role in determining a person’s intelligence.

Why are the intelligence test scores of relatives so similar?

And yet, when identical twins who have identical genes are raised in the identical household, their IQ scores still differ. How come? The shared environment refers to those environmental factors that are experienced by all relevant members of a household. For example, siblings raised in the same household have about the same level of affluence, the same number and type of books, the same diet, and so on. The nonshared environment refers to those environmental factors that are not experienced by all relevant members of a household. Siblings raised in the same household may have different friends and teachers and may contract different illnesses. This may be why the correlation between the IQ scores of siblings is greater when they are close in age (Sundet, Eriksen, & Tambs, 2008).

shared environment

Those environmental factors that are experienced by all relevant members of a household (see nonshared environment).

nonshared environment

Those environmental factors that are not experienced by all relevant members of a household (see shared environment).

302

Environmental Influences on Intelligence

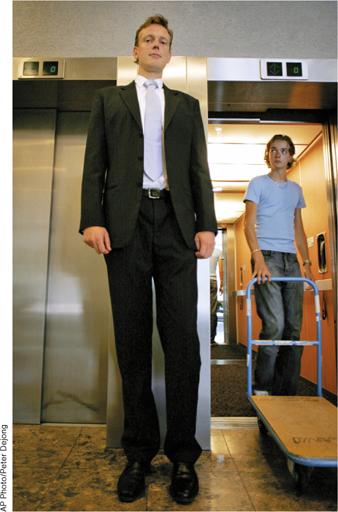

Americans believe that every individual should have an equal chance to succeed in life, and one of the reasons why some of us bristle when we first learn about genetic influences on intelligence is that we mistakenly believe that our genes are our destinies (Pinker, 2003). In fact, traits that are strongly influenced by genes may also be strongly influenced by the environment. Height is strongly influenced by genes, which is why tall parents tend to have tall children; and yet, the average height of Korean boys has increased by more than 7 inches in the last 50 years simply because of changes in nutrition (Nisbett, 2009). Genes may explain why two people who have the same diet differ in height—

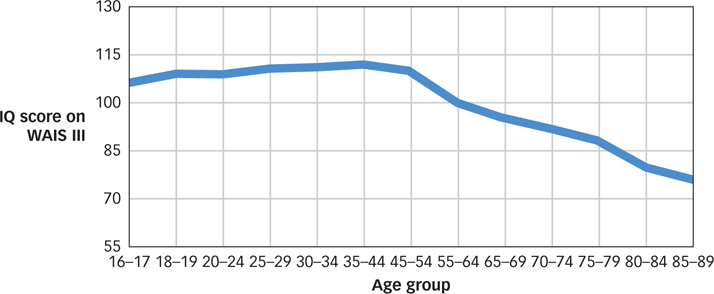

Intelligence is definitely not something that is completely fixed and determined at birth. In fact, as FIGURE 9.14 shows, intelligence changes over a person’s lifespan (Owens, 1966; Schaie, 1996, 2005; Schwartzman, Gold, & Andres, 1987). For most people, intelligence increases between adolescence and middle age and then declines in old age (Kaufman, 2001; Salthouse, 1996a, 2000; Schaie, 2005), maybe due to a general slowing of the brain’s processing speed (Salthouse, 1996b; Zimprich & Martin, 2002).

In what ways is intelligence like height?

Not only does intelligence change over the life span, but it also changes over generations. The Flynn effect refers to the accidental discovery by James Flynn that the average IQ score is 30 points higher today than it was about a century ago (Dickens & Flynn, 2001; Flynn, 2012; cf. Lynn, 2013). In other words, the average person today is smarter than 95% of the people who were living in 1900! Why is each generation scoring higher than the one before it? Some researchers give the credit to improved nutrition, schooling, and parenting (Lynn, 2009; Neisser, 1998), and some suggest that the least intelligent people are being left out of the mating game (Mingroni, 2007). But most (and that includes Flynn himself) believe that the industrial and technological revolutions have changed the nature of daily living such that people now spend more and more time solving precisely the kinds of abstract problems that intelligence tests include—

But if intelligence changes over the lifespan, then why is a strong correlation between an individual’s performance on intelligence tests that are taken at two different times (Deary, 2000; Deary et al., 2004; Deary, Batty, & Gale, 2008; Deary, Batty, Pattie, & Gale, 2008)? Well, consider two things you know about height: First, people get taller as they go from childhood to adulthood, and second, the tallest child in kindergarten is likely to be among the tallest adults in college. Height changes over the lifespan, but there is still a strong correlation between a person’s height in childhood and their height in adulthood. Intelligence is just like that. Although a person’s intelligence changes over their lifespan, the smartest youngsters tend to be the smartest oldsters.

303

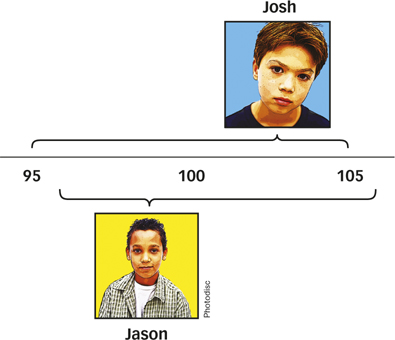

The fact that intelligence changes over the life span and across generations suggests that our genes may determine the range in which our IQ is likely to fall, but our experiences determine the exact point in that range at which it does fall (Hunt, 2011; see FIGURE 9.15). Two of the most powerful experiential factors are economics and education.

Economics

Maybe money can’t buy love, but it sure appears to buy intelligence. One of the best predictors of a person’s intelligence is the material wealth of the family in which he or she was raised—

Exactly how does SES influence intelligence? One way is by influencing the brain itself. Low-

SES also affects the environment in which the brain lives and learns. Intellectual stimulation increases intelligence (Nelson et al., 2007), and research shows that high-

Why are high SES children more intelligent?

Education

Alfred Binet believed that poverty was intelligence’s enemy, and education was its friend. He was right on both counts. The correlation between the amount of formal education a person receives and his or her intelligence is quite large (Ceci, 1991; Neisser et al., 1996). One reason is that smart people tend to stay in school, but the other reason is that school makes people smarter (Ceci & Williams, 1997). When schooling is delayed because of war, political strife, or the simple lack of qualified teachers, children show a measurable decline in intelligence (Nisbett, 2009).

Does this mean that anyone can become a genius just by showing up for class? Unfortunately not. Although education reliably increases intelligence, its impact is small, and some studies suggest that it tends to enhance test-

304

Hot Science: Dumb and Dumber

Dumb and Dumber

For most of human history, the smartest people had the most children, and our species reaped the benefits. But in the middle of the 19th century, this effect began to reverse, and the smartest people began having fewer children, a trend that scientists call dysgenic fertility. That trend continues today.

But wait. If the smartest people are having the fewest children, and if IQ is largely heritable, then why—

Some researchers suspect that two things are happening at once: Our inherited intelligence is going down over generations, but our acquired intelligence is going up! In other words, we were all born with a slightly less capable brain than our parents had, but this small effect is masked because we were born into a world that greatly boosted our intelligence with everything from nutrition to video games! How can we tell whether this hypothesis is right?

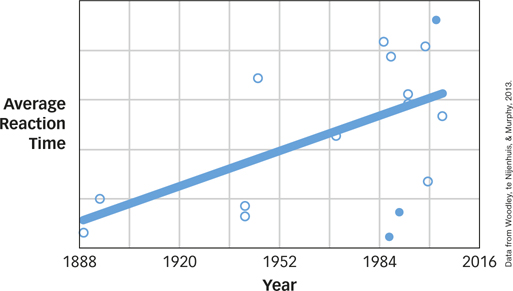

Francis Galton was the first to suggest that reaction time (the speed with which a person can respond to a stimulus) is a basic indicator of mental ability, and his suggestion has been confirmed by modern research (Deary, Der, & Ford, 2001). Recently, a group of researchers (Woodley, te Nijenhuis, & Murphy, 2013) went back and analyzed all available data on human reaction time collected between 1884 and 2004 (including data collected by Galton himself), and what they found was striking: The average reaction time has gotten slower since the Victorian era! The figure below shows the average reaction time of people in different studies conducted in different years.

Does this mean that we are innately less clever and that this fact is being obscured by the big IQ boost we get from our environments? Maybe, but maybe not. There are problems with using old data that were collected under unknown circumstances, and the participants in older studies were probably not representative of the entire population. Nonetheless, the finding is provocative because it suggests that modern life may be an even more powerful cognitive enhancer than we realize.

DATA VISUALIZATION

Nature vs. Nurture and the Correlates of Intelligence

SUMMARY QUIZ [9.5]

Question 9.16

| 1. | Intelligence is influenced by |

- genes alone.

- genes and environment.

- environment alone.

- neither genes nor environment.

b.

Question 9.17

| 2. | Intelligence changes |

- over the life span and across generations.

- over the life span but not across generations.

- across generations but not over the life span.

- neither across generations nor over the life span.

305

a.

Question 9.18

| 3. | A person’s socioeconomic status has a(n) ______ effect on intelligence. |

- powerful

- negligible

- unsubstantiated

- unknown

a.