Presenting Psychology

introduction to the science of psychology

AND IT ALL CAME FALLING DOWN

Presenting Psychology

AND IT ALL CAME FALLING DOWN

Thursday, August 5, 2010: It was a crisp morning in Chile’s sand-swept Atacama Desert. The mouth of the San José copper mine was quiet and still, just a black hole in the side of a mountain. You would never know an avalanche was brewing inside. That morning, 33 men entered that dark hole thinking they would go home to their families at the end of their 12-hour shift. Unfortunately, this is not how the story unfolded (Franklin, 2011).

Darío Segovia started his workday reinforcing the mine’s narrow passageways, a process that entailed covering the roof with metal nets. The nets were intended to catch falling rocks, like the one that had sheared off a fellow miner’s leg just a month before, but Segovia knew the nets were nothing more than a stopgap solution. The mine was going to crumble, and it was going to crumble soon. For over a century, miners had been chipping away at its rocky foundation, boring through its belly with drills and dynamite, and taking very few steps to ensure it didn’t collapse from all the human activity. The result was four miles of ramshackle tunnels randomly zigzagging into the earth like channels in an ant farm. The main tunnel was dotted with altars, remembrances of miners who had died there. It’s no wonder that the men who worked there called themselves the “kamikazes,” a reference to the Japanese suicide pilots of World War II (Franklin, 2011).

The story of the Chilean miners is largely based on Jonathan Franklin’s 33 Men: Inside the Miraculous Survival and Dramatic Rescue of the Chilean Miners. Publisher: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

after reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- LO 1 Define psychology.

- LO 2 Describe the scope of psychology and its subfields.

- LO 3 Summarize the goals of the discipline of psychology.

- LO 4 Identify influential people in the formation of psychology as a discipline.

- LO 5 List and summarize the major perspectives in psychology.

- LO 6 Evaluate pseudopsychology and its relationship to critical thinking.

- LO 7 Describe how psychologists use the scientific method.

- LO 8 Summarize the importance of a random sample.

- LO 9 Recognize the forms of descriptive research.

- LO 10 Explain how the experimental method relates to cause and effect.

- LO 11 Demonstrate an understanding of research ethics.

At about 11:30 a.m., the mountain issued its warning call. A loud splintering sound reverberated through the mine’s dim caverns. Then about 2 hours later, the mountain hit its breaking point. A section of tunnel collapsed some 1,300 feet underground (a depth of four football fields), sending a thick whoosh of stones and dirt howling through the shaft (Associated Press, 2010, August 25; Franklin, 2011). The blast of air was so strong it knocked loose Victor Zamora’s false teeth. “It was like getting boxed in the ears,” Segovia remembers (Franklin, 2011, p. 21). As miners scrambled up the dark passageways slipping on loose rocks and gravel, the mountain shook again, delivering a fresh downpour of debris. The final rumble ended with an enormous thunk—the sound of a massive boulder plugging their only viable escape. The estimated weight of the rock: 700,000 tons (Franklin, 2011).

Meanwhile above ground, workers stood by as a plume of dust collected at the entrance. They knew something was terribly wrong. Those thunderous noises from inside the mountain did not sound like routine dynamite detonations. Below the cave-in site, 33 men began making their way to “el refugio,” a safety shelter half a mile underground at the base of the mine. About the size of a studio apartment, the shelter contained two oxygen tanks, a few medical supplies, and enough food to sustain 10 miners for 2 days. Once all the men arrived, they closed the doors, turned off their lamps to save energy, and began to ponder what had just occurred. As journalists throughout the world would soon report, they had been buried alive (Franklin, 2011).

Take a minute and put yourself in the place of the Chilean miners. Squeezed into a small, dark hole half a mile beneath the earth’s surface, a place where it’s approximately 90°F with 90% humidity (Cohen, 2011), you are crowded among 32 other sweaty men. The main supply of drinking water is tainted with oil and dirt, and your daily food ration amounts to one spoonful of canned tuna fish and a few sips of milk (Franklin, 2011). Sleep is dangerous because you never know when a slab of rock might break off the ceiling and crush you. Besides, there is no dry spot to lie on; water trickles through every vein and crevice of this miserable dungeon. Crouched on the wet rock floor, you wonder what your family is doing. Have they heard about the accident? Surely, they will worry when you don’t show up for dinner tonight. Maybe a rescue team is on its way. Maybe there is no rescue team.

In this type of situation, our first concern tends to be physical safety. The average healthy adult can only survive about 3 to 5 weeks without food (Lieberson, 2004); the humid, filthy mine shaft is an ideal breeding ground for dangerous skin infections; and the dust and noxious air particles are a perfect recipe for lung disease (Associated Press, 2010, September 7; Franklin, 2011). Clearly, the miners were in grave physical danger. But is that the only type of danger they faced? Think about what might happen to a man’s mind when he is crowded into a sweltering rock pit for a prolonged period. How might it affect his thoughts and emotions? How might it affect his behavior? We could rewrite the miners’ story and point out where their story intersects with our knowledge of human behaviors, thoughts, emotions, and a variety of other topics to be covered in this textbook. For example, you can read about sleep–wake cycles (Chapter 4), stress and health (Chapter 12), and how we perceive our environments (Chapter 3). As you progress through the chapters of this book, keep in mind that you are reading the stories of real people who feel and react (with one notable exception in Chapter 11). We can better understand these individuals through the field of psychology.

What Is Psychology?

LO 1 Define psychology.

Psychology is the scientific study of behavior and mental processes. Running, praying, and gasping were observable activities of the miners when the mountain collapsed above them, all potentially a focus of study in psychology. And although their thoughts and emotions were not observable, they are valid topics of study in psychology as well.

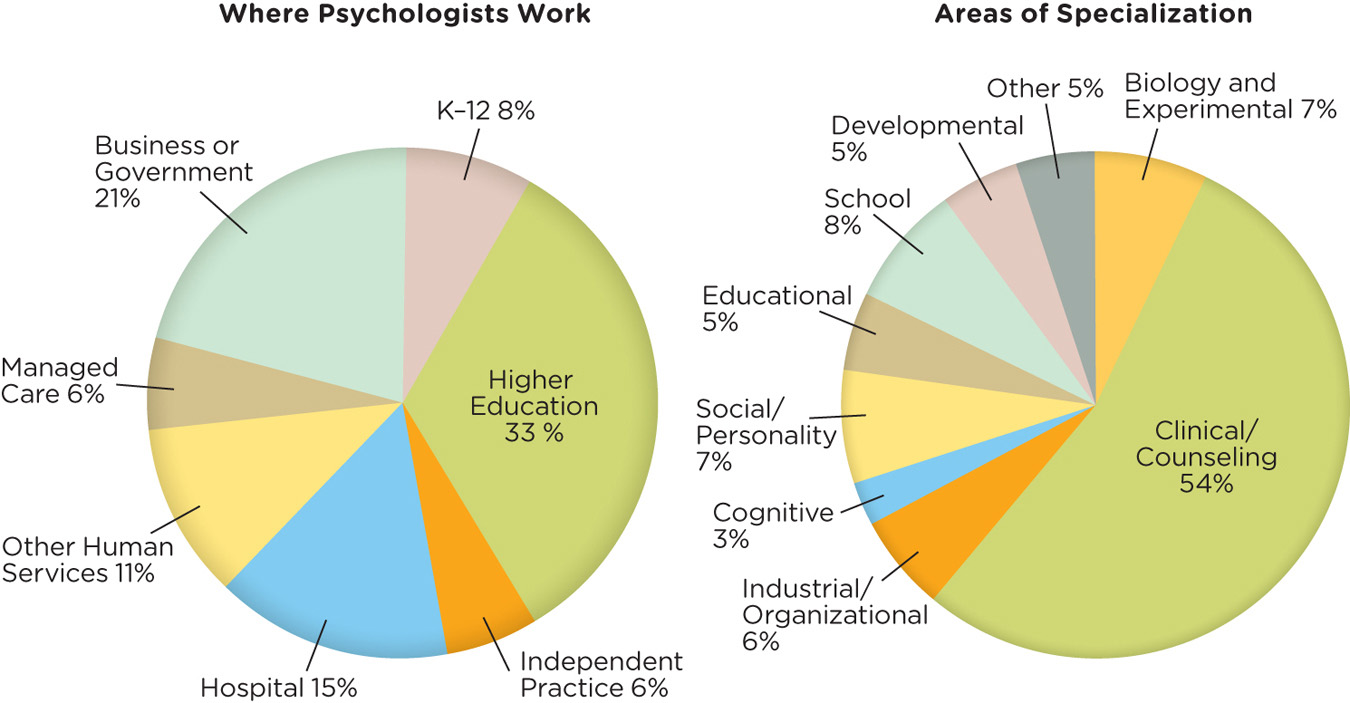

Psychologists are scientists who work in a variety of fields, all of which include the study of behavior and underlying mental processes. People often associate psychology with therapy, and many psychologists do provide therapy. These counseling psychologists and clinical psychologists might also conduct research on the causes and treatments of psychological disorders (TABLE 1.1; Chapter 13 and Chapter 14). Clinical practice is just one slice of the gigantic psychology pie. There are psychologists who spend their days observing rats in laboratories or assessing the capabilities of children in schools. Psychologists may also be found poring over brain scans in major medical centers, spying on monkeys in the Brazilian rainforest, and meeting with corporate executives in skyscrapers (Figure 1.1; see Appendix B for more on careers in psychology).

| Degree | Occupation | Training | Focus | Prescribes Medications |

| Medical Doctor, MD | Psychiatrist | Medical school and residency training in psychiatry | Treatment of psychological disorders; may include research focus | Yes |

| Doctor of Philosophy, PhD | Clinical or Counseling Psychologist | Graduate school; includes dissertation and internship | Research-oriented and clinical practice | Varies by state |

| Doctor of Psychology, PsyD | Clinical or Counseling Psychologist | Graduate school; includes internship; may include dissertation | Focus on professional practice | Varies by state |

| Master’s Degree, MA or MS | Mental Health Counselor | Graduate school; includes internship | Focus on professional practice | No |

| Mental health professionals come from a variety of backgrounds. Here, we present a handful of these, including general information on training, focus, and whether the training includes licensing to prescribe medication for psychological disorders. | ||||

Subfields of Psychology

LO 2 Describe the scope of psychology and its subfields.

Psychology is a broad field that includes many perspectives and subfields. The American Psychological Association (APA), one of the major professional organizations in the field, has over 50 divisions representing various subdisciplines and areas of interest (APA, 2012a). The Association for Psychological Science (APS), another major professional organization in the field, offers a list on its Web site of over 100 different societies, organizations, and agencies that are considered to have some affiliation with the field of psychology (APS, 2012). In fact, each of the chapters in this textbook covers a broad subtopic that represents a subfield of psychology.

Basic and Applied Research

Psychologists conduct two major types of research. Basic research, which often occurs in university laboratories, focuses on collecting data to support (or refute) theories. The goal of basic research is not to find solutions to specific problems, but rather to gather knowledge for the sake of knowledge. Explorations of human sensory abilities, trauma, and memory are examples of basic research. Applied research, on the other hand, focuses on changing behaviors and outcomes, and often leads to real-world applications. This type of research has helped generate behavioral interventions for children with sensory issues and autism, natural disaster response planning, as well as keyboard layout and improved typing performance. Applied research may use findings from basic research for ideas and inspiration, but it is often conducted in natural settings outside the laboratory and its goals are more pragmatic or practical.

Misconceptions About Psychology

FIGURE 1.2

What Is This? Throughout this book, you’ll find parenthetical notes like this one for the research published by Stanovich in 2010. This citation tells you the source of research being discussed. If you want to know more about a topic, you can look up the source and read the original article. Information provided in this brief citation allows you to locate the full reference in the alphabetized reference list at the back of the book (page R-1). There are many systems for citing sources, but this textbook uses the format established by one of psychology’s main professional organizations, the American Psychological Association (APA).

Looking at Figure 1.1, you may have been surprised to learn about the variety of subjects that psychologists study. If so, you are not alone. Researchers report that students often have misconceptions about the field of psychology and psychological concepts (Landau & Bavaria, 2003). Truth be told, we can’t blame students. Most of what the average person knows about psychology comes from the popular media, which fails to present an accurate portrayal of the field, its practitioners, and its findings. Frequently, guests who are introduced as “psychologists” or “therapists” by television talk show hosts really aren’t psychologists as defined by the leading psychological organizations (Stanovich, 2010).

One common misconception is that psychology is simply common sense, meaning it is just a collection of knowledge that any reasonably smart person can pick up through everyday experiences. This sense of the obviousness of psychological findings might be related to the hindsight bias, or the feeling that “I knew it all along.” When a student learns of a finding from psychology, she may believe she knew it all along because the finding seems obvious to her in retrospect, even though she wouldn’t necessarily have predicted the outcome beforehand. We fall prey to the hindsight bias in part because we are constantly seeking to explain events; we come up with plausible explanations after we learn of a finding from psychological research (Lilienfeld, 2012).

Or sometimes, students insist they know all there is to know about child development, for example, because they are parents. Just because a young man has experience as a father does not necessarily mean he can observe his family like a scientist. As you learn more about the human mind and how it works, you will start to see that it is quite fallible and prone to errors (Chapter 6), which calls into question the accuracy of our observations and common sense. The problem is that common sense and “popular wisdom” are not always correct (Lilienfeld, 2012). Common sense is an important ability that helps us survive and adapt, but it should not take the place of scientific findings. TABLE 1.2 identifies some commonsense myths that have been dispelled through research.

| Myth | Reality |

| “Blowing off steam” or expressing anger is good for you. | Unleashing anger actually may make you more aggressive (Lilienfeld, Lynn, Ruscio, & Beyerstein, 2010). |

| Most older people live sad and solitary lives. | People actually become happier with age (Lilienfeld et al., 2010). |

| Once you’re married and have kids, your sex life goes down the tubes. | According to the Global Sex Survey (2005), people ages 35–44 are having more sex than any other age group. |

| Once you are born, your brain no longer generates new neurons. | Neurons in certain areas of the brain are replenished during adulthood (Eriksson et al., 1998). |

| Listening to Mozart and other classical music will make an infant smarter. | There is no solid evidence that infants who listen to Mozart are smarter than those who do not (Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff, & Eyer, 2003). |

| When people reach 40 years of age, they are bound to have a “midlife crisis.” | Evidence suggests that only a quarter of middle-aged people hit a breaking point and suffer from such a crisis (Almeida, 2009). |

| People with schizophrenia and other mental disorders are dangerous. | Only 3–5% of violent crimes are committed by people with serious mental disorders (Arkowitz & Lilienfeld, 2011). |

| Psychological research has debunked many pieces of commonsense wisdom, including the notion that “opposites attract.” Similarity turns out to a better predictor of romantic attraction, with studies suggesting that people are more drawn to those with cultural backgrounds, values, and interests resembling their own (Lott & Lott, 1965). | |

Psychology is a Science

Unlike common sense, which is based on casual observations, psychology is a rigorous science based on meticulous and methodical observation, as well as data analysis. You may be surprised to learn that psychology is a science, in the same sense that chemistry and biology are sciences. And although people often feel as if they can explain others’ behaviors, we probably would all agree that we are bewildered by some of the things people do. In some of these types of situations, the methods used by psychologists can help explain what prompts behaviors.

You don’t have to pour chemicals into test tubes or crunch numbers on a computer to be considered a scientist. Science is not defined by the subject studied or the equipment used. It is a systematic approach to gathering knowledge through careful observation and experimentation. It requires sharing results and doing so in a manner that permits others to duplicate and therefore verify work. Using this scientific approach, psychologists have determined that many popular commonsense beliefs, such as people only use 10% of their brains, are not true. It appears there is a great deal of “psychomythology,” which is “the collective body of misinformation about human nature” (Lilienfeld et al., 2010, p. 43). Reading this textbook, you might discover that some of your most cherished nuggets of commonsense wisdom do not stand up to scientific scrutiny. (Did you recognize any of them among the myths listed in TABLE 1.2?)

The Goals of Psychology

LO 3 Summarize the goals of the discipline of psychology.

Now that we’ve defined psychology, it’s time to explore the goals of this discipline. What exactly does psychology aim to accomplish? The answer to this question varies according to subfield, but there are four main goals: to describe, explain, predict, and control behavior. These goals lay the foundation for the scientific approach used in psychology and the experiments designed to carry out research. Let’s take a closer look at each goal.

Describe

Goal 1 is simply to describe or report what is observed. We also can use findings from observations to help plan future research. Imagine a psychologist who wants to describe the aftereffects of being trapped in a mine for a prolonged period. What kind of study would she conduct? To begin with, she would need access to a group of people who have survived this type of ordeal, such as the 33 Chilean miners. Following the men’s rescue, she might request permission to perform some assessments to evaluate their moods, social adjustment, and physical health. She might even monitor the miners over time, conducting more assessments at a later date. Eventually, she would describe her observations in a scientific article published in a respected journal.

Explain

Goal 2 is to organize and understand observations of behaviors. Researchers gathering data must try to make sense of what they have observed. If the psychologist noticed an interesting pattern in her assessments of the miners, she might develop an explanation for this finding. Let’s say the miners’ health after confinement seemed to be poor compared to their prior status; then the psychologist might look for factors that could influence immunological health. Searching the scientific literature for clues, she might come across studies of people with experiences in similar situations, for example, sailors living and working for long periods in submarines. If she determined that health-related changes were associated with the confinement experienced in a submarine, this could help explain the changes in the miners’ medical status, although she still would have to conduct a controlled experiment to identify a causal relationship between confinement in a mine and health-related issues.

Predict

Goal 3 is to predict behaviors or outcomes. When we observe behavior patterns, we can make predictions about what will happen in the future. If the researcher determined that the miners’ reduced immunological status resulted from sleep deprivation caused by confinement, then she could predict that prolonged confinement in another setting (such as a submarine) might lead to the same outcome: sleep deprivation, and therefore decreased immunity.

Control

Goal 4 is to use research findings to shape, modify, and control behavior. When we say “control behavior,” your mind might conjure up the image of an evil inventor who takes control of someone’s mind and makes him carry out a malicious plot. This is not the kind of control we are talking about. Instead, we are referring to how we can apply the findings of psychological research to shape and change behaviors in a beneficial way. Perhaps the researcher could use her findings to help a mining company hire workers who might be better suited to the confining characteristics of mining. Working in small spaces like mines and submarines is not for everyone.

You have now learned the definition, scope, and goals of psychology. You will soon explore the ins and outs of psychological research: how psychologists use a scientific approach, the many types of studies they conduct, and the ethical standards or guidelines for acceptable conduct that guide them through the process. But we will start with some history, meeting the people whose philosophies, insights, and research findings molded psychology into the vibrant science it is today.

show what you know

Question 1.1

1. Psychology is the scientific study of __________ and __________.

behavior; mental processes

Question 1.2

2. A researcher is asked to devise a plan to help improve behavior in the confined space of subway trains. Based on his research findings, he creates some placards that he believes will modify the behavior of subway riders. This attempt to change behaviors falls under which of the main goals of psychology?

- describe

- explain

- predict

- control

d. control

Question 1.3

3. How is common sense different from the findings of psychology? If one of your friends says, “I could have told you that!” when you describe the findings of various studies on confinement, how would you respond?

Common sense is a collection of knowledge that any reasonably smart person can pick up through everyday experiences and casual observations. Findings from psychology, however, are based on meticulous and methodical observations of behaviors and mental processes, as well as data analysis. Many people respond to psychological findings with hindsight bias, or the feeling as if they knew it all along. If the results of a study seem obvious, someone may feel as if she “knew it all along,” when in reality she wouldn’t have predicted the outcome ahead of time.