The Scientific Method

LO 7 Describe how psychologists use the scientific method.

Critical thinking is an important component of the scientific method, the process scientists use to conduct research. The goal of the scientific method is to provide empirical evidence, or data from systematic observations or experiments. An experiment is a controlled procedure involving scientific observations and/or manipulations by the researcher to influence participants’ thinking, emotions, or behaviors. In the scientific method, an observation must be objective, or outside the influence of personal opinion and preconceived notions. Humans are prone to biases (Chapter 7), but the scientific method helps to minimize their effects.

Suppose a researcher had tried to determine whether any of the Chilean miners was running a fever. He might have asked the crew’s “doctor,” Yonny Barrios, to place his hand on each man’s forehead, but Barrios’ measurement of “fever” could have been different from the researcher’s. A more objective approach would have been to send down a thermometer to the mine. Observations that are truly objective do not differ from one person to the next based on beliefs or opinions. A thermometer will read the same whether it’s being used by Yonny Barrios or a new mom.

Steps of the Scientific Method

STEP 1: Develop a Question

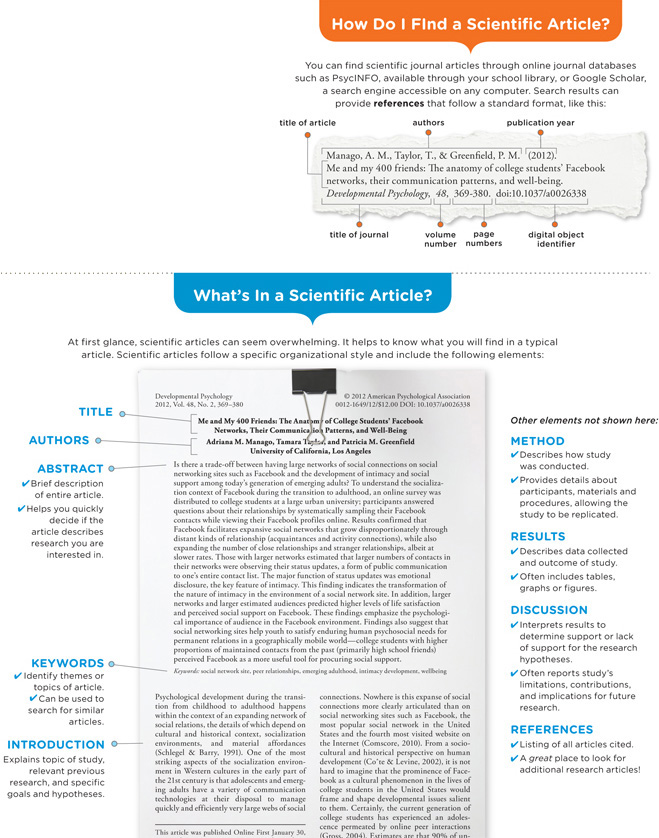

The scientific method typically begins when a researcher observes something interesting in the environment and comes up with a research question. A great way to start this process is to read books and articles written by scientists. (See Infographic 1.2 to get a sense of how best to find and read an article.) Imagine that a psychologist has decided to study the psychological health of the trapped miners. While reviewing the literature on this topic, he comes across several studies suggesting that disaster survivors face an elevated risk for depression (Bonanno, Brewin, Kaniasty, & La Greca, 2010). This makes the psychologist wonder: Will Los 33 experience rates of depression similar to those of other disaster victims, or do their unique circumstances place them in a category all their own?

STEP 2: Develop a Hypothesis

Once a research question has been developed, the next step in the scientific method is to formulate a hypothesis (hī-′pä-thə-səs), a statement that can be used to test a prediction. The psychologist might come up with a hypothesis that reads something like this: “If we treat half of the survivors from the San José mining disaster with therapy and put the other half on a waiting list for therapy, those on the waiting list will be more likely to receive a diagnosis of depression within 5 years of rescue.” The data collected by the experimenter will either support or refute the hypothesis. Hypotheses are difficult to generate for studies on new and unexplored topics; in this situation, a general prediction may take the place of a formal hypothesis.

While developing research questions and hypotheses, researchers should always be on the lookout for information that could offer explanations for the phenomenon they are studying. For a study on depression, this might entail reviewing theories about the causes of depression. Theories synthesize observations in order to explain phenomena, and they can be used to make predictions that can then be tested through research. Many people believe scientific theories are nothing more than unverified guesses or hunches, but they are mistaken (Stanovich, 2010). A theory is a well-established body of principles that often rests on a sturdy foundation of scientific evidence. Evolution is a prime example of a theory that has been mistaken for an ongoing scientific controversy. Thanks to inaccurate portrayals in the media and elsewhere, many people have come to believe that evolution is an active area of “debate” among scientists when, in reality, it is a theory embraced by the overwhelming majority of scientists, including most psychologists. We all have opinions about various issues and events in our environments, but how are these opinions different from theories? Please use what you have just learned about critical thinking to answer this question.

STEP 3: Design Study and Collect Data

Once a hypothesis has been developed, the researcher designs a procedure to test it. Operational definitions specify the precise manner in which the characteristics of interest are defined and measured. For example, the psychologist might have used a depression scale to measure the mood of the miners, and then defined depression based on a cutoff point (anyone with a score greater than 40, for example). According to the scientific method, a good operational definition helps others understand how to perform an observation or take a measurement.

The researcher then collects the data to test the hypothesis. Gathering data must be done in a very controlled fashion to ensure there are no errors, which could arise from recording problems, or biases from different environmental factors. We will address the basics of data collection later in the chapter.

STEP 4: Analyze the Data

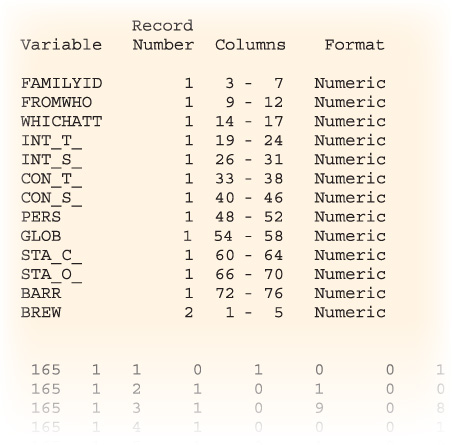

The researcher now has data that need to be analyzed, or organized in a meaningful way. As you can see from Figure 1.3, rows and columns of numbers are just that, numbers. In order to make sense of the “raw” data, one must use statistical methods. There are two basic types of statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics are used to organize and present data, often through tables, graphs, and charts. Inferential statistics go beyond simply describing the data set. Using this type of statistical analysis, it is possible to make inferences and determine the probability of events occurring in the future (for a more in-depth look at statistics, see Appendix A).

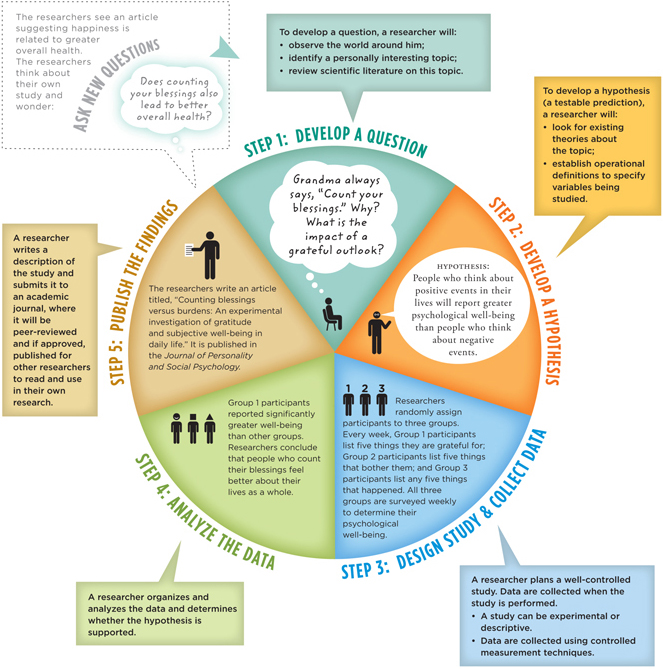

Once the data have been analyzed, the researcher must ask several questions: Did the results support the hypothesis? Were the predictions met? He evaluates his hypothesis, rethinks his theories, and possibly designs a new study based on the analyses. This cyclic procedure is an important part of the scientific method because it allows us to think critically about our findings. In the hypothetical depression study of Los 33, what if the researcher found no differences between the therapy and nontherapy groups? Was the type of therapy used ineffective? Were the tools for measuring depression problematic? If these ideas are worth pursuing, the researcher could develop a new hypothesis and embark on a study to test it. Look at Infographic 1.3 to get a sense of the cyclical nature of the scientific method.

INFOGRAPHIC 1.2: How to Read a Scientific Article

Psychologists publish their research findings in peer-reviewed, scientific journals. Scientific journal articles are different from news articles or blog posts that you might find through a typical Internet search. When you read news articles or blog posts about a research study, you can’t assume these sources accurately interpret the study’s findings or appropriately emphasize what the study’s original authors think is important. For a full description of the background, methodology, results, and the application of a research study’s findings, you must read a scientific article.

STEP 5: Publish the Findings

Once the data have been analyzed and the hypothesis tested, it’s time to share findings with other researchers who might be able to build on the work. What is the point of doing research if no one ever reads about it or has access to the findings? This typically means writing a scientific article and trying to get it published in a scholarly, peer-reviewed journal. Journal editors send a submitted manuscript to subject-matter experts, or peer reviewers, who review it and make recommendations for publishing, revising, or rejecting the article altogether.

The peer-review process is notoriously meticulous, and it helps provide us with more certainty that findings from research can be trusted. This approach is not foolproof, of course. There have been cases of fabricated data slipping past the scrutiny of peer reviewers. In some cases, these oversights have serious consequences for the general public. Case in point: the widespread confusion over the safety of routine childhood vaccines.

In the late 1990s, researchers published a study suggesting that vaccination against infectious diseases caused autism (Wakefield et al., 1998). The findings sparked panic among parents, including the actress Jenny McCarthy, who led a march in Washington, D.C., calling for changes in vaccination policies. Concerned that their children would develop autism, many parents shunned the shots, putting their children at risk for life-threatening infections such as the measles. The study turned out to be fraudulent and the reported findings were deceptive, but it took 12 years for journal editors to retract the article (Editors of The Lancet, 2010). Why did the retraction take so long? One reason is that it took years for researchers to investigate all the accusations of wrongdoing and data fabrication (Godlee, Smith, & Marcovitch, 2011). The investigation included interviews with the parents of the children discussed in the study, which ultimately led to the finding that the information in the published account was inaccurate (Deer, 2011).

Since the publication of that flawed study, several high-quality investigations have found no solid support for the autism-vaccine hypothesis (Honda, Shimizu, & Rutter, 2005; Madsen et al., 2002; Taylor et al., 2002). Still, the publicity given to the original article continues to cast a shadow: Approximately 18% of Americans believe that vaccines cause autism and 30% are “not sure” (Harris Interactive/HealthDay poll, 2011). Ultimately, even though the peer-review process is a safeguard against fraud and inaccuracies, sometimes the process is not successful, and problematic findings make their way into peer-reviewed journals.

INFOGRAPHIC 1.3: The Scientific Method

Psychologists use the scientific method to conduct research. e scientific method allows researchers to collect empirical (objective) evidence by following a sequence of carefully executed steps. In this infographic, you can trace the steps taken in an actual research project performed by two psychologists who were interested in the effect of “counting your blessings” (Emmons & McCullough, 2003). Notice that the process is cyclical in nature. Answering one research question often leads researchers to develop additional questions, and the process begins again.

Publishing an article is a crucial step in the scientific process because it allows other researchers to replicate the experiment, which might mean repeating it with other participants or altering some of the procedures. This repetition is necessary to ensure that the initial findings were not just a fluke or the result of a bias in one particular experiment.

In the case of Wakefield’s fraudulent autism study, other researchers tried to replicate the study for over 10 years, but could never establish a relationship between autism and vaccines (Godlee et al., 2011). This fact alone made the Wakefield findings suspect. The more a study is replicated and produces similar findings, the more confidence we can have in those findings.

Ask New Questions

Most studies generate more questions than they answer, and here lies the beauty of the scientific process. The results of one scientific study raise a host of new questions, and those questions lead to new hypotheses, new studies, and yet another collection of questions. This continuing cycle of exploration uses critical thinking at every step in the process.

show what you know

Question 1.1

1. We all hold opinions about various issues and events in our environments, but how are those opinions different from theories?

An opinion is a belief or attitude that is not based on research, and may completely result from personal experiences, often without any scientific evidence to support it. Theories synthesize research observations and can be used to explain phenomena and make predictions that are testable with the scientific method. Theories are often well-established bodies of principles that rest on a solid foundation of evidence.

Question 1.2

2. A researcher identifies affection between partners by counting the number of times they gaze into each other’s eyes while in the laboratory waiting room. The cutoff for those who would be considered very affectionate partners is gazing more than 10 times in 1 hour. The researcher has created a(n) __________ of affection.

- theory

- hypothesis

- replication

- operational definition

d. operational definition

Question 1.3

3. A __________ synthesizes observations to try to explain phenomena, and we can use it to help make predictions.

- theory

- hypothesis

- descriptive statistic

- peer-reviewed journal

a. theory