Research Designs

THE BIG WAIT

The miners’ first 17 days underground were intense and grueling, but now they faced the ultimate test of psychological endurance: waiting up to 4 months for rescuers to bore an escape tunnel. Could they go the distance? The circumstances of their cave-home were not exactly conducive to mental stability: no personal space, zero privacy, stifling heat, nauseating odors, minimal contact with family and friends, and loads of time to kill.

The miners’ first 17 days underground were intense and grueling, but now they faced the ultimate test of psychological endurance: waiting up to 4 months for rescuers to bore an escape tunnel. Could they go the distance? The circumstances of their cave-home were not exactly conducive to mental stability: no personal space, zero privacy, stifling heat, nauseating odors, minimal contact with family and friends, and loads of time to kill.

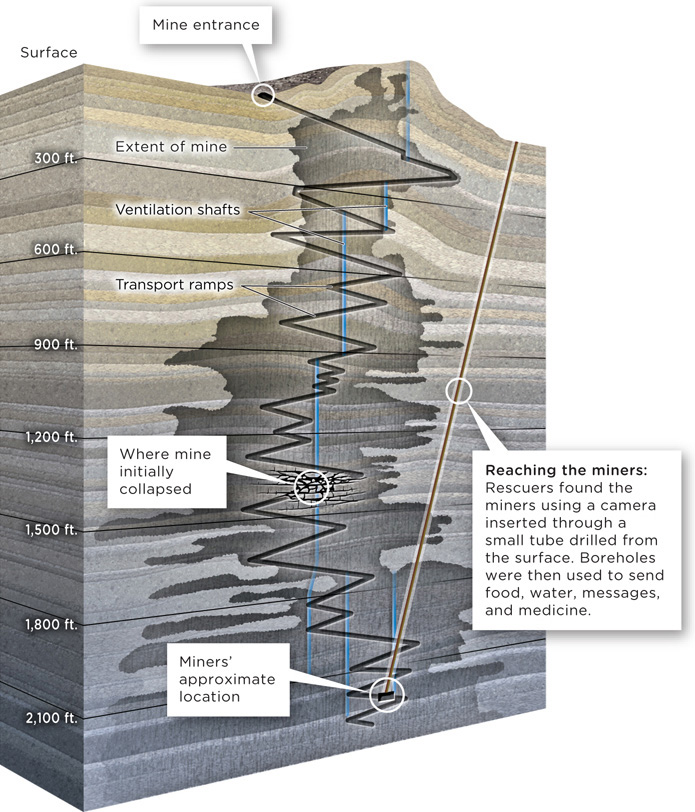

Recognizing the extraordinary psychological battle the miners faced, a team of psychologists was assembled to oversee their mental health (Franklin, 2011). Physicians and the lead psychologist Alberto Iturra began holding daily conference calls using a makeshift telephone line running through one of the boreholes. [A total of three narrow bore holes were drilled in order to facilitate communication and the delivery of food, medicine, and other necessities (Associated Press, 2010, August 30).] The therapist–patient relationship was congenial at first, but those feelings soon turned sour when Iturra began to meddle with the miners’ communications. He recommended, for example, that the men be allotted only 1 minute for their first conversation with family members. According to one miner, Iturra actually got on the line and said “cut” when a miner’s time was up. The psychologists also began to read personal letters sent from the miners to their families, and vice versa, censoring every piece of mail flowing in and out of the mine. Apparently, they were concerned that certain types of news (such as problems in the family or financial troubles) might be too much for the already stressed miners to bear. But this censorship incited something of a rebellion among the group (Franklin, 2011).

When the miners started to skip their conference calls, the psychologists punished them by taking away their few pleasures. “OK, you don’t want to speak with psychologists? Perfect. That day you get no TV, there is no music—because we administer these things,” lead physician Dr. Jorge Diaz admitted to reporters (Franklin, 2010, September 18). The rewards and punishments did not go over so well. “These government psychologists…they are treating these strong men like children,” one of the miner’s partners told journalists. “They are humiliating them. They are punishing them, like in a reality show. If they are bad, they don’t get treats or special food. If they rebel, they are chastised. You cannot treat grown men, tough miners, like this” (McDougall & Allen-Mills, 2010, October 18).

Mental health experts across the globe weighed in on the matter. Psychiatrist Nick Kanas of the University of California deemed it unwise to censor communications between the miners and the outside world. “I would not screen anything…. Otherwise you are setting up a basis for mistrust,” Kanas told journalist Jonathan Franklin (Franklin, 2011, p. 152). “Any attempt to be not entirely forthcoming [by rescuers] could be seen as a lack of trust,” said psychologist Lawrence Palinkas of the University of Southern California in an interview with Discovery News. “ (O’Hanlon, 2010, August 31).

The situation, in terms of the number of victims trapped, their distance underground, and the length of time they were buried, was entirely unprecedented (Spotts, 2010, September 7). No psychologist had ever studied human beings in a scenario quite like this. There were no “lessons learned” from past experience, no guidelines to follow, and certainly no research on the subject. The best Iturra and his colleagues could do was draw on studies of people in similar situations—such as miners who had been trapped for shorter periods of time, sailors confined in submarines, and astronauts on long-term space missions (Franklin, 2011).

Research Basics

Choosing the right research design, or type of scientific study, is crucial for collecting the most useful data. We will discuss two major categories of research design—descriptive and experimental—but before we do so, let’s take a look at some of the concepts relevant to nearly all types of scientific research.

Variables

Virtually every psychology study includes variables, or measurable characteristics that vary, or change, over time or across people. In chemistry, a variable might be temperature, mass, or volume. In psychological experiments, researchers study a variety of characteristics pertaining to humans and other organisms. Examples of variables include personality characteristics (shyness or friendliness), cognitive characteristics (memory), number of siblings in a family, gender, socioeconomic status, and so forth. A psychologist studying the miners might be interested in variables related to mood, leadership qualities, competitiveness, or educational background. In many experiments, the goal is to see how changing one variable affects another. In the Chilean miner example, you might be interested in knowing how the delivery of empanadas, a delicious stuffed pastry, affected the miners’ moods. Once the variables for a study are chosen, researchers must create operational definitions that offer their precise descriptions and manners of measurement.

Population and Sample

LO 8 Summarize the importance of a random sample.

How do researchers decide who should participate in their studies? It depends on the population, or overall group, the researcher wants to examine. If the population is large (all college students in the United States, for example), then the researcher selects a subset of that population called a sample.

There are many methods for choosing a sample. One way is to pick a random sample, that is, theoretically any member of the population has an equally likely chance of being selected to participate in the study. Think about the problems that may occur if the sample is not random. Suppose a researcher is trying to assess attitudes about banning supersized sugary sodas in the United States, but the only place she recruits participants is New York City, where there is a ban on supersized sugary sodas. How might this bias her findings? New York City residents do not constitute a representative sample, whose members’ characteristics closely reflect those of the population of interest.

It is important for the researcher to make sure she chooses a representative sample, because this allows her to generalize the findings, meaning to apply the information from the sample to the population at large. Let’s say that 44% of the respondents in her study believe supersized sugary sodas should be banned. If her sample were representative, then she may be able to infer that this finding from the sample is representative of the entire population: “Approximately 44% of people in the United States believe that supersized sugary sodas should be banned.”

Informed Consent

The researcher has chosen the population of interest, and she has identified her sample, but she needs to make certain that these people are comfortable participating in her research. Before she can begin to collect data, she must obtain informed consent, or acknowledgment from the participants that they understand what their participation will entail, including any possible harm that could result. Informed consent is the participant’s way of saying, “I understand my role in this study, and I am okay with it,” and it’s the researcher’s way of ensuring that participants know what they are getting into.

Debriefing

Following the study, there is another step of disclosure known as debriefing. In a debriefing session, researchers provide participants with useful information related to the study. In some cases, participants are informed of the deception or manipulation they were exposed to in the study, information that couldn’t be shared with them beforehand. You will soon learn why a small dose of duplicity sometimes comes in handy for scientific research. And rest assured, all experiments on humans and animals must be approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) to ensure the highest degree of ethical standards.

The topics we have touched on thus far—variables, operational definitions, samples, informed consent, and debriefing—apply to psychology research in general. You will see how these concepts are relevant to studies when we explore descriptive and experimental research, in the upcoming sections.

THE MINERS GET THEIR WAY

After nearly a month of working with lead psychologist Alberto Iturra, the miners demanded that he be dismissed. They were tired of the psychologists reading and editing their letters, searching care packages, and punishing them for refusing to go along with Iturra’s agenda. The miners issued an ultimatum: Either Iturra goes, or we stop eating. Their strategy worked, at least temporarily; Iturra agreed to take a 1-week break, while another psychologist, Claudio Ibañez, took charge (Franklin, 2011).

After nearly a month of working with lead psychologist Alberto Iturra, the miners demanded that he be dismissed. They were tired of the psychologists reading and editing their letters, searching care packages, and punishing them for refusing to go along with Iturra’s agenda. The miners issued an ultimatum: Either Iturra goes, or we stop eating. Their strategy worked, at least temporarily; Iturra agreed to take a 1-week break, while another psychologist, Claudio Ibañez, took charge (Franklin, 2011).

Ibañez was much more relaxed in his approach. He put an end to the letter-editing and package-tampering and, in doing so, he placed more faith in the miners’ ability to cope with whatever news might arrive from the world above. Ibañez was trained in positive psychology (Franklin, 2011), a relatively new approach to psychology that focuses on the positive aspects of human nature (a topic we will return to at the end of the chapter).

Ibañez’s more laid-back style was a welcome relief to some of the miners, but soon it became clear that his method had its drawbacks as well. With much of the censorship stopped, families reportedly began to sneak forbidden items like marijuana, amphetamines, and chocolate into their care packages. Yes, chocolate. Sweets were a “no-no” because they could aggravate the miners’ fragile dental health. Try living with an untreated toothache for days, weeks, or months. The arrival of prohibited items soon sparked envy and resentment among some of the men, disrupting the delicate social structure within the mine (Franklin, 2011).

show what you know

Question 1.1

1. Psychology studies focus on __________, which are characteristics that vary or change over time or across people.

variables

Question 1.2

2. A researcher is interested in studying college students’ attitudes about banning supersize sodas. She randomly selects a sample of students from across the nation, trying to pick a that will closely reflect the characteristics of college students in the United States.

- variable

- debriefing

- representative sample

- representative population

c. representative sample

Question 1.3

3. Why do researchers need to ensure that they collect data from a representative sample?

A representative sample has members with characteristics similar to those of the target population. Characteristics to consider could include gender, age, socioeconomic status, and so forth. Without a representative sample, one should not generalize the study findings to the larger population.